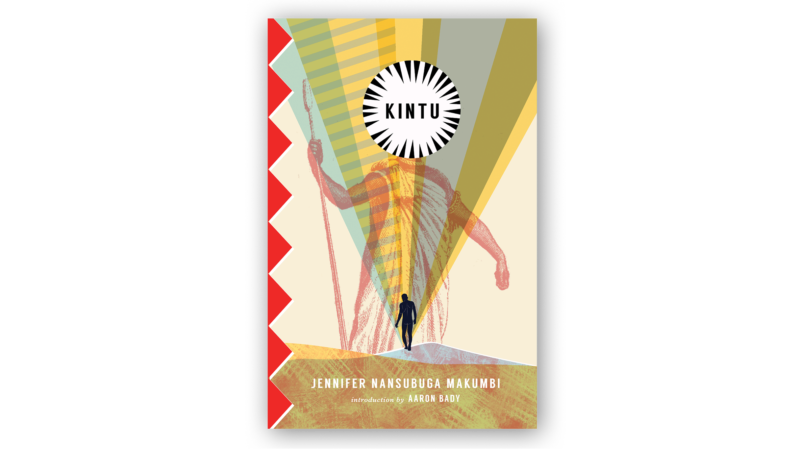

Postcolonial literature is often thought of as a conversation between a native culture and a Western power that sought to dominate it. The common tendency to read books from the Global South this way is regrettable, since it perpetuates the fantasy that all of world history is little more than a reaction to those of us in the West. Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi’s marvelous Ugandan epic, Kintu (May 2017, Transit Books), explodes such chauvinism. Rather than a simplistic rendering of Uganda’s history that might offer some context for her nation’s present state—before and after the British “protectorate,” or the infamous dictator Idi Amin, or the epidemic of AIDS—Makumbi instead seeks something essential about the Ugandan imagination that might help describe a more comprehensive history for her troubled home.

The novel’s action revolves around a reunion of a Ganda (one of the nation’s predominant ethnic groups) clan descended from a quasi-mythological figure named Kintu Kidda, and the bulk of the book is taken up with unspooling the biographies of a number of his descendants. Perhaps none of these small histories is so deeply colored by tragedy as Isaac Newton Kintu’s, whose mother—raped by a teacher—chose his name because her “last lesson in school was on the law of gravity.” Given such an inauspicious start, it’s hardly surprising when “six months after his birth, when Isaac Newton failed to turn into a cute baby,” his mother abandons him to an abusive grandmother. Suubi Kintu’s upbringing is similarly gloomy, as her caretaker aunt raises her in “a single room in an unfinished house. The window was boarded up; sunlight from the corridor was thin… There was no ceiling above. Two electrical wires snaked along the beams to the wall and came down. One ended in a hanging socket, the other in a switch also unattached to the wall. Both were covered in dust and cobwebs.”

Such tales of woe are what a Western reader will probably have been bracing for as soon as he read the word “Uganda,” but Makumbi’s privileged characters share in Suubi and Isaac Newton’s suffering in a way that betrays something deeper at work in her book than just cable-news-ready depictions of poverty. Kanani Kintu is a priest of an obscure Christian sect called the Awakened, but God is no help in preventing one of his twin children, Ruth, from becoming pregnant at fourteen. And even Miisi Kintu, a retired Cambridge-educated professor, loses ten of his twelve children to the twin scourges of war and AIDS.

The antecedents for these problems seem obvious—shortsighted missionaries, neglectful bureaucrats, deficient healthcare providers. Even Makumbi’s treatment of Uganda’s history has a tone of predestination to it. “After independence,” she writes,

Uganda—a European artifact—was still forming as a country rather than as a kingdom in the minds of ordinary Gandas […] Meanwhile, the other fifty or so tribes looked on flabbergasted as the British drew borders and told them that they were now Ugandans. Their histories, cultures and identities were overwritten by the mispronounced name of an insufferably haughty tribe propped above them.

This, in short, is Uganda as the West knows it: an imagined nation doomed from its conception by arbitrary borders. Even as she invokes this widely held, fatalistic perspective on her homeland to describe its present conditions, however, Makumbi seems intent on seeking out something enduring in its national character that might provide a little more perspective. She begins the novel in 1750, a century and a half before British rule, when the Great Lakes region of Africa was split among a number of kingdoms and tribes. Kintu Kidda himself is a provincial leader who adopts the son of an impoverished Tutsi laborer after he arrives in the village carrying “the shivering newborn, still covered in birth-blood.” Kintu raises the child, but he inexplicably dies after Kintu cuffs him on the ear. Understandably incensed, the biological father curses Kintu’s family, promising him that “even death will not bring relief.” The threat has teeth: Kintu’s heir falls ill and expires on the day of his wedding, and the patriarch’s beloved wife dies by suicide soon afterward.

That it is a Tutsi who curses this Ganda family is hardly an accident—one of the “50 or so tribes” that would grow so resentful of Ganda power two centuries later, the Tutsi are best known in the West as the victims of the 1994 genocide in neighboring Rwanda. In Kintu, the dynamic between Tutsi and Ganda serves to illustrate the tribal resentments that fueled much of the twentieth century’s strife (Idi Amin, for example, was a member of the so-called Nubian peoples of northwestern Uganda, and many of the estimated three hundred thousand he killed were from neighboring rival tribes).

These internal dynamics, Makumbi makes clear, have had as profound an impact on the current state of Uganda as the legacy of English rule (and if the real estate devoted to one over the other in the book is any guide, the tribal divisions have had a much more lasting impact). In an interview staged by Kenya’s Kwani Trust in 2014, Makumbi observed that “postcolonial studies of African literature have a way of limiting your imagination to the arrival of colonization or the arrival of Europe… It’s as if Africa didn’t exist before the colonizers arrived.” The histories of African peoples are as long as any other continent’s (well, longer), but those centuries before the Europeans came should not be mistaken for some prelapsarian period of comity. No, even as Makumbi subtly illustrates the cultural connective tissue that unites the contemporary and pre-colonial versions of Uganda elsewhere, Kintu’s curse serves as a tangible manifestation of the durability of Ugandan discord.

Acknowledging the persistence of suffering is one thing—explaining it, another. Makumbi is less interested in offering an answer than capturing the extent to which Ugandans will go to change their fates. However incredulous about the actual power of Kintu Kidda’s curse, each member of the clan still ends up returning to his ancestral home in order to assist in its “restoration.” Suubi comes holding only the quiet hope that the ceremony might exorcise a ghostly twin that’s been haunting her. “Don’t mistake me,” she tells a distant relative. “I am neither Christian nor atheist: I am just plain… These things have no place in the modern world.”

The contradiction between her rejection of a metaphysical realm where things like spirits and curses appertain and the agony her ghost has caused her points to the enormous difficulty of the task Makumbi has set herself in attempting to explain the struggles of Ugandans. A mark of sophistication is the ability to dismiss an inherited legend as superstition, but these are characters who welcome the superstition as just another way to interpret and understand their history. “As long as there are Africans in the world,” Suubi’s interlocutor responds to her skepticism, “there will always be someone seeking these things.”

As the ceremony proceeds, Makumbi seems to suggest that the soul of her nation can only be understood by seeking out—even at that “remotest level of existence”—all the contradictions and cruelties that shape it. To confront it, one must be as willing to explore the spiritual world as they are the waking one, just as the nation must be understood to have been shaped not solely by English colonizers but by tribal histories with much less clear-cut heroes and villains as well. The comings and goings of rulers, native or not, has shaped the peoples of Uganda, sure. But as Makumbi makes clear, those forces do not define them. Thinking “two ways at once” does.