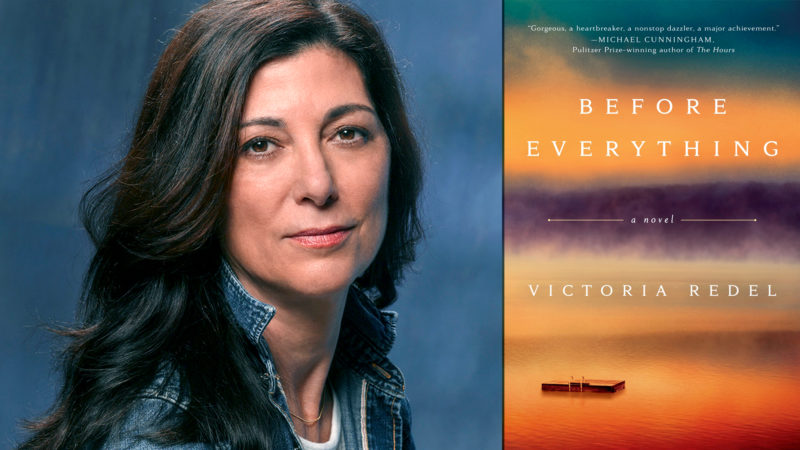

The author of five works of fiction and three works of poetry, Victoria Redel’s work has spanned both time and form. Her new novel, Before Everything (Viking, June 2017), catalogues the lives of five women—from their adolescence to one of their deaths—in short, syncopated sections that jump back and forth in time and point of view. The architecture of Redel’s often lyrical prose soars beyond ambition and signals the arrival of a true master. The book’s short, blunt sentences thrust us into the “ongoingness” of a scene, to enlarge a fleeting moment and make us examine it. “Something flashed blue. A wing, blue. A jay?”

These five women have marriages and lovers and hosts of admirers and friends. However, their relationships, as women and confidants, define them. A quiet yet revolutionary statement is at work in the warmth and depth of Redel’s pages about the not-so-subtle strength demanded of womanhood. The book lifts the veil on the power dynamics of female relationships—investigating the lasting power of allegiances of the heart. “This is what they had always done together,” Redel says of how they talk and listen to each other. “The necessity of saying it out loud. Talking for the sheer pleasure, the hilarity. To be witness to the stunning accumulation of a life.”

We don’t simply look to fiction as a place to escape, but a place to admire, to learn. Here, we are afforded the pleasure of all three. Redel grafts herself with swift and subtle assurance onto the readerly unconscious; it is an honor and a pleasure to be immersed amongst the lives of these women. To watch Redel pay homage to their strength, their humor, their complexity, their intelligence. The many roles they juggle both in the family and the larger sphere of the world. Below we discussed: How does one sculpt such a thing?

—Annie DeWitt for Guernica

Guernica: Before Everything is a large trove of a novel, packed with wisdom about life and death and the unending curve of marriages and friendships, their shift and flow, the places they betray and bolster. I wondered if you might talk a bit about form. The word that comes to mind is bricolage. How did you conceive of this myriad patchworking together of lives?

Victoria Redel: I was emerging from a big loss, the death of my best and oldest friend and began writing because it’s my way to manage experience and gives me a sense of purpose. The writing, at first, was about actual people. The scenes—I don’t know if you could call them scenes, sometimes just a moment, a thought someone was thinking, a glass lifted to lips for a sip of water—came up organically. Soon that shifted into fiction with fictional characters. Then a shape began emerging. Theodore Roethke has a line in his poem “The Waking” that reads: “We learn by going where we have to go.” That seems true of many things, certainly of writing. I began to understand that if the novel warranted including so many characters, then I needed to give them the opportunity. Originally I hadn’t conceived of a novel that shifts between many points of view. That would have been too scary. The architecture built slowly. It kind of dilated—layering in scenes, shifting the point of view inside a scene by reentering it, maybe just a moment later, through a different character. Because much of the foreground story happens in one house, having a less linear, mosaic architecture allowed for the situation of the novel to expand in multiple directions at once while the short bursts, its mosaic pieces, let me have the compression of a poem inside a novel.

Guernica: I found myself falling in with the women characters, loving them, as though I too had known them forever. You capture the ordinary nature of life and death in achingly honest, plainspoken terms. And yet, you elevate the mundane in a way that reminds me of Sharon Olds’s work. Your attention to the detail of the natural world as well as interior emotion create a synergy that made me feel as though I too lived among these people, was privy to their darkest secrets. How did you go about conceiving the details of each of these women’s narrative arcs? Helen the famous artist; Ming and her law practice; Caroline and her wild manic sister; Molly the therapist dealing with her teenage daughter’s rebellion; and Anna, who seems to hold the group together?

Victoria Redel: You live long enough and listen to enough people [tell you their] big and the small problems, the secrets and the happiness, and you see that there’s no shortage of complexity in every person. The key in any novel, in any effective writing, is to select details that are distinct and still echo between characters. Flannery O’Connor says, “The fact is that the materials of the fiction writer are the humblest. Fiction is about everything human and we are made out of dust, and if you scorn getting yourself dusty, then you shouldn’t try to write fiction.” That seems exactly right. This attention to thingness, the physical world, creates character. Precision of observation becomes the way we can move inside how a character experiences the world. What any character notices, smells, hears is probably more telling and more reliable than what they say or what they feel.

Guernica: Hannah Tinti writes, “Victoria Redel bears witness to a remarkable group of women, effortlessly weaving back and forth through time, each thread revealing the cracks and secrets of their complex lives while also drawing them closer…. She proves that female friendship is the quiet, steady engine that truly runs the world.” I couldn’t agree more. Each of these women struck me as a powerhouse in her own way. I wanted to ask them so many questions about my own life—am I doing it right? There seems to be a quiet feminism afoot here.

Victoria Redel: The lives of ordinary women are not written about nearly enough. And there’s nothing ordinary about those lives. I detest when people say women are multitaskers as if what women have done through all of time is something new, created out of a business-efficiency model. It’s been my ambition always to allow women characters the whole big range—sexual, intellectual, emotional, maternal, furious, funny, loyal, determined, frustrated. I could keep adding to the list—tough, fierce, fearful, brilliant. The women I know are all of this and then some. I’m tired of simple dualities. And yes, feminist. Of course, feminist. I’m the youngest of three sisters. Our mother was an intense woman. She was a ballet dancer and created a large ballet school. She worked every day. Our grandmother lived till she was one hundred and three, through three centuries, many wars and countries, and was a feminist, though I don’t think she knew that word.

Guernica: This book dismisses the cliché of women as necessary enemies fighting for the male gaze. In fact, their friendships, rather than their marriages, or even their children, seem to fuel them. I wondered if you might talk about how you claimed that power?

Victoria Redel: It wasn’t a power that needed to be claimed. It’s truly how I feel. I don’t buy any image of women as enemies or inevitably bitchy. Are women angry or ambitious? Yes, sometimes—and why shouldn’t they be? Maybe men believe our primary focus is the male gaze, but what woman in the midst of her life would agree? It is part of an oversimplified portrayal of women that has nothing to do with women’s actual lives. The women in Before Everything have been one another’s close confidantes over many years. They bear one another’s contradictions, they speak up to one another, and they show up for each other. I don’t think this is exceptional, and not only among intimate friends. Hasn’t every woman had the experience of walking into a public bathroom—let’s say at highway rest stop—and some woman washing her hands next to you says the most personal revealing statement? Maybe she looks up and catches your eye in the mirror, says, “Whoa, when did I start looking like my mother?” Or she might say, “I might have to kill my husband and my kids before this road trip is over.” And you nod and laugh, “I know. I know.” You say, “I’ve already killed mine three times this summer.” And then you both dry your hands and walk out feeling a lot better.

Guernica: What struck me most was that the relationship between the narrator and Anna was, in some ways, the most significant relationship of both of these women’s lives. I couldn’t help but cheer as you quietly upended traditional ideas of marriage and heteronormativity and was reminded of Michael Cunningham’s A Home At The End of The World, where a nontraditional group of three friends live as roommates and both men play father roles to the woman’s child. However, where Cunningham’s book uses first-person to explore these internal perspectives, you chose to use close third. I wondered if you might talk about that decision. It allows your narrative voice to remain constant, and yet the close third dips into the various characters’ lives, creating a kind of kaleidoscopic interiority.

Victoria Redel: I believe in the power of women’s friendships. Before Everything is an opportunity to go as far into that power as I can. By creating a multiplicity of perspectives, I could keep reaching further inside the great family that friendship constructs. I think you’re right that this is one of Michael Cunningham’s great subjects. We have the family we are born into, and then we have the family we make over a lifetime. Maybe a couple of families. And we count on those families, those networks of love and strength. Is this revolutionary? It seems natural, healthy, and inevitable. In Before Everything, Reuben is such an important character to me. He’s not one of the women friends, though they all love him. He’s not really Anna’s husband anymore, but he steps up. Like the women, he loves through time, he understands that love is an action and that even though his marriage to Anna has in some fashion failed, he’s true to her and to the full spectrum of their life.

Using your terrific word, “kaleidoscopic,” close third gave me the opportunity to keep kaleidoscopically turning through these various characters’ interiorities and, hopefully, still manage a coherent music overall. I often built the narrative in only paragraph-long sections. Maybe in all of eight sentences, Caroline looks over at Reuben who is cleaning out the fridge, and she thinks about the suffering of caregivers. And then in the next section—which might be two pages long— Reuben fantasizes about getting out on his bike, pushing himself to a physical brink. So there are quick shifts from one interiority to another interiority and then there are long sections, and I hoped third-person provided overall unity. I was trying for an orchestral effect. It was a serious challenge and I worried a lot. I wanted to keep moving through time and people, I wanted to allow for longer swaths of narrative and then for swifts, even abrupt ones. But I didn’t want to lose the reader. I am never looking to lose the reader. That was the challenge.

Guernica: Anna is a very honest person. She doesn’t take any bullshit from anyone, even from her disease. She takes charge of orchestrating her own death. Her death becomes the central question around which the book is organized. In that way, there is a fugue-like structure to these various characters’ responses to mortality, which they examine through the lens of Anna’s choice not to continue treatment. I couldn’t help but feel as though this portrait was an homage to a life you’d observed. Is that what it is to take claim of life—to decide for yourself how it ends?

Victoria Redel: If we are lucky, we can make choices that feel right for ourselves. And those choices really differ person to person. We all have such different thresholds of what is acceptable for a life. I’ve had several very dear friends and family die—some in long, protracted ways, some shockingly fast. We don’t always have the chance to choose how we’ll leave this earth but making decisions, facing our mortality, is brave. I wasn’t trying to make a prescription, but to honor a person’s choice and how that choice is borne by others.

Guernica: Your sentences in Before Everything, as in all your work, are exquisite. Short, blunt. I was reminded of a lecture you taught at Columbia where you said words were mathematical sets—when you use one word, you have access to all the subsets (and opposite subsets) within it and, in fact, have a responsibility to that awareness.

Victoria Redel: I’ve got to say, no shortage of people will howl with laughter at the idea that I spoke about mathematics. But though I might not have grasped higher math, I really did love sets and subsets, what I now think is taught as Venn diagrams. That’s about third-grade math. But as you know—what I meant was that each word has a fuller implicative load. Every word comes with the possibility of its associational words, its opposites, it sonic twins, its vowel patterns. It’s all part of what helps create the language, voice, themes, the fabric of the novel. The specific words govern what actually happens in the book. I’ve often wished I could be a writer who tears through a rough draft. I know many great writers who do, and their attention to each word comes much later in the process. I write with a belief that each word, each sentence, gives me the possibility of what comes next. I’ve come full circle to Roethke’s “We learn by going where we have to go.” What a beautiful villanelle. So full of paradox. Quite mystical.