Not long before he turned five, my son asked if he could keep a document on my computer’s desktop that would contain his efforts at learning to write—or type. The practice is imitative; he sees me type. This is typical social learning. Some of what he types is lifted from magazines and books, including what he typed on the first page, advertising copy from maybe a travel company or vacation destination, I forget: TURNS OUT YOU CAN BE AWESOME IN TWO PLACES AT ONCE. (For a time he was writing in all caps, like an ad.) More recently he was writing the names of the planets.

To gain permission to use the computer, he asks if he can write “silly things,” and normally I say yes. The document he’s written runs some fourteen pages, and lots of it is nonsense, which he often asks me to try to read aloud. What does this say, Dad? “jhtrewqasdfghjkl;’zxcvbnm.” (You do your best.) This interaction is also imitative; there’s a line from a popular children’s book filled with nonsense words, and no pictures, that conspires with kids to make grown-ups reading aloud “have to say silly things!” Things like: “BRROOOOoOG BRROOoOOOG BRROOOOoOG” and “Ba-DOOONGY FACE!!!!”

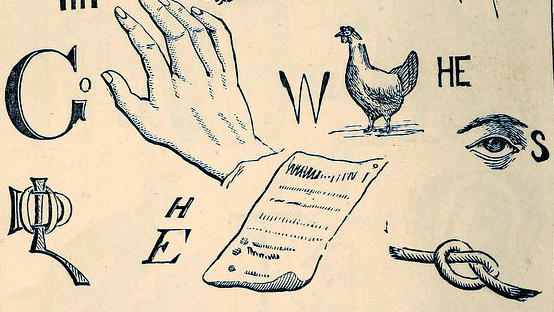

Some of what my son writes has begun to make sense, like this:

Bbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbb

bbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuu

uuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuttttttttttttttttttttttttt

ttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttttt

And this:

mom

can

do

it

Here he’s gone Joycean:

Iss

Kissnm

Misskiss

Piscuits

Piscuits I read as a mild curse, another form of imitation he seems to enjoy.

My son and I still kiss on the lips. At home. At the door to his kindergarten class. Before a swimming lesson at the Y, in front of everyone. We do a thing before bed on nights when my wife is reading stories that he calls a running-hug-and-kiss, which is what it sounds like. He runs down the hall, jumps at me, I catch him, and we hug and kiss. “Good night,” or “Have fun,” I say. “See you in an hour, after school, in the morning time.”

All this kissing is imitative, too. Though with good kissing, when is it not? You imitate each other by turning a head, craning up or down, meeting in the middle, until you don’t, or can’t, any more. In time, and maybe in love, the imitation becomes second nature; you forget you’re both following the other’s lead. And unlike with a punch, a kiss is more painful when it misses and arrives as a glancing blow, when you realize she can’t stand it anymore. But with everyone you’ve ever kissed, there was a first kiss and there was, or will be, a last. It can be heartbreaking; it can be a relief; in the end, it can be the end.

With my son, I say I will miss the kissing when it ends, but that may not be true. I know it’s the right and sentimental thing for fathers of my generation, our era, to say. But it’s also the fearful thing to say, like, “They grow up so fast,” which only means that I’m getting older, more quickly it seems.

At a point I suspect my son will initiate a new kind of imitation. We’ll show affection in a different way. My son knows and seems to love men who kiss each other, so it won’t be that exactly. Ours are not romantic kisses. (Although when I ask what makes his kisses with me different than my kisses with his mother, he says it’s that I have to lift him up.) But unless I’m wrong, for a time at least he’ll continue saying Mom can do it, while with me he’ll stop. Piscuits, I’ll think. This will be typical social learning. We’ll stop kissing.

Until we can start again at the end—I’ll find comfort in that, I hope—sometime before I say, “Good night,” sometime before I can’t say, “See you.”

The Kiss: Intimacies from Writers is available from Norton in February 2018.