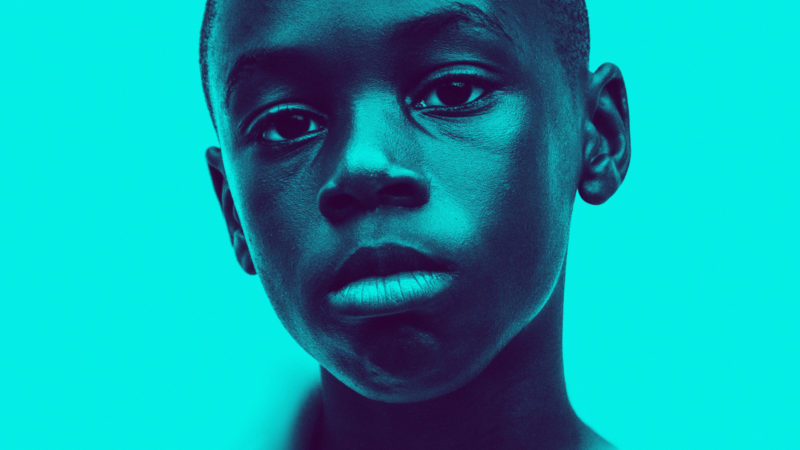

Black skin under an illuminating blue light: a light that highlights the nuances that collectively create the black male image. Moonlight is a meditation on identity, selfhood, and the courage it takes to seek out one’s personal truth. The film opens with the image of a black boy running through empty and abandoned spaces. The boy continues to run and hide throughout the film, changing only the places in which he seeks solace.

We first meet Chiron as an undersized nine-year-old nicknamed Little, who we follow through his teen years to adulthood. The roles are poignantly performed by Alex Hibbert, Ashton Sanders, and Trevante Rhodes and beautifully illuminated by cinematographer James Laxton, who worked with director Barry Jenkins on numerous projects, and their creative cohesion is evident. The terror of watching a young boy’s life unfold with a mother who buries her pain in the glass pipe, leaving her son vulnerable to the unruly Miami streets, is balanced by the striking beauty of sensual frames lit by an array of blues and pinks, accompanied by an evocative musical score. The film is not dialogue heavy, but the emotional gestures and formidable silences speak eloquently in a way that words could never quite capture. The effect is a visually stunning coming-of-age story that shows the complex decisions, relationships, and encounters that bruised the black boy’s skin until he became a man cloaked in scabs. His scabs become his armor. But armor can be as harmful as it is protective.

As a child, Little tries to understand who he is, and why he likes to dance while his peers insist on the joys of football and physical brawls. He grapples with what a “faggot” is, as he himself isn’t sure if he’s gay. His mentor, Juan, a street hustler (played by Mahershala Ali) who identifies with the boy’s sensitivity from his own childhood in Cuba, informs him that at some point he must define himself outside of what people want him to be.

Little never quite understands how to do that, since it is rare to find a role model for how to be queer and black where he lives in the Miami projects (or anywhere else, really). As he grows into a tall, lanky, uncomfortably hunched pimple-faced teenager, people start calling him Chiron. Despite his physical transformation, he’s still self-conscious, and his circumstances have worsened. His bullies are stronger, their fists are balled tighter, his mother is no longer a functional addict, and the man who deals to her, Chiron’s mentor, is gone, because the hustle don’t always last.

In the creases of these violent confrontations with pain and increasing intolerance, Little, the gentle and sensitive boy, transforms to his adult self, Black.

Black is Chiron’s learned idea of man, masculinity as he understands it. He is strong, intimidating, and homophobic. He’s a hustler who drives a long car called a SLAB (slow, loud, and banging) in the south, with rims that shine. His teeth shine, too, but you can only see glimmers of his fronts when he smirks; never a full smile. His muscles are definitive under his dark T-shirt, like the ones most associated in the hood with a physique sculpted during a daily routine in a cellblock. His pants sag just enough to create a slight limp that gives bounce to his thin gold chain. He no longer hunches his back, but when Black peers into the mirror, somewhere in there, perhaps in his eyes, the way they search for the floor, we can still see Little.

When Black reunites with a childhood friend with whom he had his first and only homosexual encounter in high school, his friend asks, “Who is you, man?” Everything from Chiron’s demeanor to his voice to his physical build has transformed. But his friend remembers Chiron at his most vulnerable, when they sat under the moon together at the shore of the Atlantic Ocean talking about their pain and exploring each other’s bodies with one hand and gripping the sand with the other. That one night they were the solace they each desperately craved.

In 1896 Paul Laurence Dunbar wrote the poem “We Wear the Masks” about the survival apparatus worn by black people in America as a means of protection and preservation against the savagery of slavery. “We wear the mask that grins and lies,” he says.

It hides our cheeks and shades our eyes,—This debt we pay to human guile;With torn and bleeding hearts we smile,And mouth with myriad subtleties.

At nine years old, Chiron is taught to “be tough” “be a man” and “fight.” But the film begs the question, when does a little black boy ever get a chance to be a boy? To cry and express emotion, or simply to be held and protected. These innate human necessities become a luxury in communities like the one that he grew up in. But Dunbar spoke of wearing the mask in a different context than the one Chiron faces. Dunbar spoke of protection from the white gaze, the “double consciousness” that W.E.B. Du Bois speaks of in The Souls of Black Folk, which is relevant here, too, but not completely applicable.

In Moonlight, we see a third layer of code switching that Chiron requires for survival, one where he must participate in his own oppression by declaring anti-gay sentiments not only to be treated with respect, but to stay alive. I can’t help but think about the open letter that Frank Ocean released with his debut LP, Channel Orange, where he speaks about falling in love with a man in his hometown of New Orleans, known then as a murder capital, and both of them feeling unsafe to speak it out loud, even though they barely had the language to begin to express what they felt. Ocean said his emotional illiteracy manifested itself into anger. “I’ve screamed at my creator,” he writes. “Screamed at the clouds in the sky. For some explanation. Mercy maybe.” Ocean wasn’t able to admit this love affair aloud via Channel Orange until he left for Los Angeles, just as Black was unable to face his feelings for his childhood friend until he relocated to Atlanta. Perhaps there is freedom in distance. Perhaps it is impossible to define yourself when you’re surrounded by those who witnessed you collect your wounds. Black, Dunbar, Du Bois, and Ocean are evidence that generations of masking will continue if toxic masculinity prevails.

This is one of the most accurate and textured portrayals of the black male experience ever to appear on screen, despite the fact that its black women are illustrated so flatly, as they almost always are in film. Moonlight is ultimately a story of redemption. A black man who attempted to barricade his heart is able to get in his car to drive to another state and ask another black man to hold him, to touch him, to hear him the way he had over ten years ago. To help him, if only for a moment, take off his mask.