For the last week of August 2003, Janet and I returned for a third summer to Stonington, Maine, where we paddled our ocean kayaks among the granite islands of Penobscot Bay off Deer Isle. On a bright and windy day, we kayaked out to Isle au Haut, about five and a half miles offshore. Getting there and back required leaving the shelter of the smaller islands to cross Merchant Row, so named for the large ships that once set full sail while heading into the Atlantic. That evening we were proud of ourselves and buoyant with joy. On the last day of our holiday, I sat in my boat, gently rocked by the waves in the cove below the place we were renting. Janet and I had agreed that in 2004 our summer vacation would last two full weeks—maybe we would paddle out to Butter Island and even camp overnight. The water was cold and very clear. Seaweed streamed in with the little waves and back with the outflow, and I thought: Remember this. Remember how it feels.

When I celebrated my fiftieth birthday a few days later, I felt young in my body and deeply happy, with a lover who had my full attention. I was settled in mind, and sure that the next decades would be very like the life I was then leading. Less than a month later, I was out for my regular seventeen-mile bicycle ride when a branch caught in my front spokes. The bicycle stopped dead. In an instant, I was thrown off; my chin hit the pavement; my neck snapped back, fracturing my fifth and sixth cervical vertebrae; the broken bone scraped my spinal cord. A rapid-response helicopter from Hartford Hospital landed in the graveyard on the other side of the country road from where I had fallen, and I began the rest of my life.

My legs are paralyzed. I no longer sweat, one of the bizarre consequences of the injury to my central nervous system. I have functional use of my hands, though no fine motor control, and full range of motion in my arms but pitiful strength. I cannot sit up without support; I cannot control my bladder and must “manage” my bowels. Orgasms are a thing of the past.

Yet I remember quite vividly how my strong and able body felt, despite my lack of capacity. Thirteen years later, I can still recall in minute detail how deeply content I was sitting in my kayak, watching the seaweed stream below me, the sharp chill of the ocean water running through my fingers. I know how my body felt as I crested the hill where I broke my neck, though I have no memory of the accident. I remember setting out for the ride, the two-mile mark, but nothing more. Nonetheless, I can feel my exertion upon starting up the hill, the cool fall air, the sweat on my face, my determination to maintain a steady cadence of pedal strokes. I can feel myself breathing hard as I climbed. I am confident in these facts because by the time of the accident, I’d ridden that route many hundreds of times, and the traces of both muscular and mental effort live on in my body.

Because of my transformation, I have worked hard to conceptualize how embodied memory works—like the muscle memory that allows you to ride a bike even if you haven’t been on one for years. Some phenomenologists use the neologism “bodymind” and teach us that there is no separating body from mind. I think that’s right. What am I to make, then, of my profoundly altered state? The loss of the body that I was and the life that I had made is affectively as well as physically profound, and the sense of loss can be suddenly piercing when I see a cyclist with good form or ocean kayaks strapped to the roof of a car. For an instant, a vividly embodied memory of riding or paddling will come over me. Then the light will change, making a claim on my attention I can’t ignore, but the preemptory present cannot make me feel less alien to myself in such moments.

I recognize in that alienation the force of grief. Grief is a current running below the surface of my unremarkable days, sometimes drawing me into eddies where I spin round and round, sometimes pulling my mind insistently away from the day’s work and rushing me downward. Stiff-minded resistance is of little avail. We are counseled to surrender ourselves for a time after loss to the sheer force of grief, because only by giving yourself over to it will the pain lessen.

In a metapsychological text titled “Mourning or Melancholia: Introjection versus Incorporation,” the analysts Nicolas Abraham and Mária Török develop the concept of introjection as a process by which the infant responds to the absence of the mother’s breast in the mouth—that first irreparable loss. This absence pushes the infant to explore the oral cavity and begin to find her way to language. The early satisfactions of the mouth…are…replaced by the novel sensations of the mouth now empty of that object but filled with words pertaining to the subject…. So the wants of the original oral vacancy are remedied by being turned into verbal relationships with the speaking community at large…. Since language acts and makes up for absence by representing, by giving figurative shape to presence, it can only be comprehended or shared in a ‘community of empty mouths.’

Abraham and Török go on to argue that melancholic affect follows from the failure to introject. Melancholics are unable to find language to represent their loss because they respond to the absence of the loved one by incorporating it—swallowing…what has been lost, as if it were some kind of thing. By objectifying and consuming loss, the subject refuses to accept what is no more and refuses to mourn, sparing herself pain but thereby blocking communication. Loss produces a melancholy affect when objectified and swallowed whole. The mouth remains empty, and the subject downcast.

I am trying to find in the speaking community at large a way to address the transformation I have suffered and to represent the losses I have suffered. In this community of empty mouths, everyone has suffered loss and must make an effort to represent something once precious, now absent. Loss is never simply over and done, stripped of its power to wound. Mourning is never a linear sequence of stages, despite that pamphlet in your doctor’s office, but more a cyclical, iterative process that repeatedly returns you to what once was.

I had been so happy because I had in middle age at last been able to ask and answer the question, What do you want? I had it, and I lost it.

Nothing is that simple, of course. But every morning I must make an effort to gather myself to live another day. I’ve come to think that the distinction between mourning and melancholia is a useful heuristic, but no more. At the rehab hospital, there was a somewhat obtuse psychologist, aptly named Dr. Bellevue, always on the alert for the depression that grays out the days of many with spinal-cord injuries. I cried every single day over the many months I was there, yet in weekly meetings with my medical team, I vigorously declared through my tears that I was not depressed—no, I was infinitely sad, buffeted and broken by grief. I was unwilling to accept a narrative that dulled my grief into depression, and I was, and remain, deeply suspicious of the teleological story that “it gets better,” which organizes events retrospectively and then waits for you to show up. Thirteen years later, the pain of grief is less overwhelming, but it’s still insistent. I think that might be a good thing.

Sigmund Freud theorized that the process of mourning works out the loss of any dearly held ideal, precious object, or precious person. The need for this work is clear: Reality-testing has shown that the object no longer exists…[and] [n]ormally, respect for reality gains the day. Decathecting or withdrawing from what is lost is, nonetheless, agonizing. Each single one of the memories and expectations in which the libido is bound to the object is brought up and hyper-cathected, and detachment of the libido is accomplished in respect of it. Why this by which the command of reality is carried out piecemeal should be so extraordinarily painful is not at all easy to explain…. In Freud’s account, the terrible work—much of it unconscious—of detaching from what’s lost moves forward, and time closes up the rent in your world. You slowly attach to new objects.

I’ve lost not a person, but a body. With it went my sense of self. Gone are physical capabilities in which I delighted, a tactile world in which I felt at home. I was comfortable in my skin, vain about my strength and athletic ability, blissfully committed to sex. Cooking, eating, drinking, and conversation afforded pleasure to body and soul. Why wouldn’t I want to swallow whole what I have lost, incorporate it so as to carry it with me always?

I shelter in my mind my lost body. The genius of melancholy thus shadows my inner life. It consorts awkwardly with the abundance that surrounds me and which I readily, happily affirm. My lover loves me still, good fortune beyond measure. From the first, she told me, “I’m your physical lover.” She meant it then, and she means it now. The love of my caretakers and friends, and the support of our families, helped us through the first two years. We are rich in material things, according to my lights, and have beautifully altered the spaces we live in to make them accessible to me. I was able to return to work, half-time, at Wesleyan University, because voice-recognition software enables me to write. I communicate with colleagues and students via email and grade my students’ papers online. We sold my much-loved Triumph motorcycle and bought a new minivan that the Connecticut Bureau of Rehabilitation adapted with hand controls, so I drive independently.

That adaptation cost as much as the van itself, and I was eligible for help from the Bureau because I had a job—thus works the bureaucratic logic of “rehabilitation,” which assured I would be a tax-paying citizen, rather than a burden on the state. I know that most disabled people can’t find work and live truly precarious lives dependent on Social Security disability insurance and Medicaid, both of which are always vulnerable to politically mandated cuts, but now more than ever. I’m fully alive to the advantages I enjoy, which are considerable.

And yet grief acts as a kind of scrim through which I see a world robbed of its brilliance. By the time I broke my neck, Jeff, my only sibling, had been living with multiple sclerosis and ever-increasing paralysis for over thirty years. Six years after my accident, he died from the disease that had implacably destroyed neural circuits over the course of his adult life. Grief is a promiscuous emotion that picks up any sorrow. Memories of a long life lived before spinal-cord injury mingle with lively recollections of the brother I once had, the body he had been, the body I once was. Sometimes I’m furious. More often, grief silently ensures that the outer world stays slightly out of focus.

If these are the effects of grief, why do I ward off forgetting? Even as the unconscious process of detachment Freud theorized is at work within me, I remain committed to incorporation. I want to remember my brother in his youthful strength and the vividly embodied pleasures that I shared with Janet when my life felt shot through with joy.

Perhaps this is a perverse labor that offends good sense. I hope so. I had been so happy because Janet and I were together committed to the perverse pleasures of a queer life, which you make with other people. It’s a community thing. The wildness of undomesticated sex lets in light and air. It doesn’t matter so much what you do in your own practice—sex in the park, sex at the club, sex in bed. Sexual practices rely on shared knowledge and the cultural institutions of queerness. One of my favorites: that New York City restaurant where the pretty boys who are the servers wear tight pink t-shirts, each emblazoned with a typed word on the front and one on the back. Wearing lovely fitted jeans, our waiter showed “sugar” when he faced us and “cream” walking away. Or the dyke punk band “Tribe 8,” whose name refers to the lesbian sex act of “tribadism,” that is, lesbian frottage. In other words, a queer world in which sexuality is out in public. Thinking about grief, then, I am drawn to what scholar Ann Cvetkovich calls “an archive of feeling” in her book by that name, which focuses in part on the archive built up by queer communities responding to the trauma of the AIDS epidemic, when loss threatened to overwhelm the living.

Such an archive would include the 1989 volume of October, in which Douglas Crimp famously rethinks the familiar activist imperative—Don’t mourn, organize!—by arguing for mourning and militancy together. Crimp explores the ways that the culture of public sex elaborated in the 1970s created an ethos of community that sustained gay men in the 1980s and ’90s, when AIDS killed them by the thousands. Activists organized the community so that those who were well helped the ones who were ill. Gay men taught one another “how to have sex in an epidemic” (the title of a 1983 booklet by Richard Berkowitz and Michael Callen) and publicized how to make safer sex sexy.

The militant organizing and direct actions of ACT UP were driven by the fury of the many who had lost friends and lovers. They knew they were abandoned by a government that refused to recognize AIDS as the epidemic it so clearly was, while church and state together encouraged active hostility toward homosexuality. Crimp argues that militants could sustain their activism only by being open to the feelings of grief, abandonment, fear, and rage that are part of the processual work of mourning. Otherwise depression would strand them, exhausted, on the sofa, watching TV.

Recalling that time in a 2003 interview titled “The Melancholia of AIDS,” Crimp clearly distinguishes depression from a melancholia queerly different from Freud’s. If mourning is achieved by severing attachments to the lost object and moving on, in melancholia there is a form of attachment to loss that can be politicizing. Maintaining an attachment to the lost object, the lost loved one, or…a lost gay sexual culture can be productive of an antimoralistic politics. José Esteban Muñoz has shown us some of the ways we might perform just such a politics. He argues that melancholia…is a mechanism that helps [people of color, lesbians, and gay men] (re)construct identity and take our dead with us to the various battles we must wage in their names—and in our names. Activists did just that when they organized an action to make public the dying that was happening everywhere around them but too often hidden behind closed doors. Like Abraham and Török’s melancholic swallowing…what has been lost, as if it were some kind of thing, they took with them beloved bodies lost to death, and strewed their ashes on the White House lawn. Those remains remain. Unmarked all these years later, despite a proposal to list the dead on a plaque affixed to the fence, there they lie. Doubtless many in ACT UP were visited by melancholy, but, unlike depression, queer melancholy urges words and acts to save the dead and the living alike.

This history is helpful to me as I consider the body that I’ve lost yet carry with me. My damaged spinal cord has caused irreversible paralysis, most of the endless deficits of which you can’t see. Similarly, the work of caring for a person so injured unfolds in what we call private life. I’m a scholar, so as I lived on, I began to read in the field of disability studies. I discovered the term “bodymind,” a phenomenological neologism that makes sense to me, since body and mind are both distinct and inseparable.

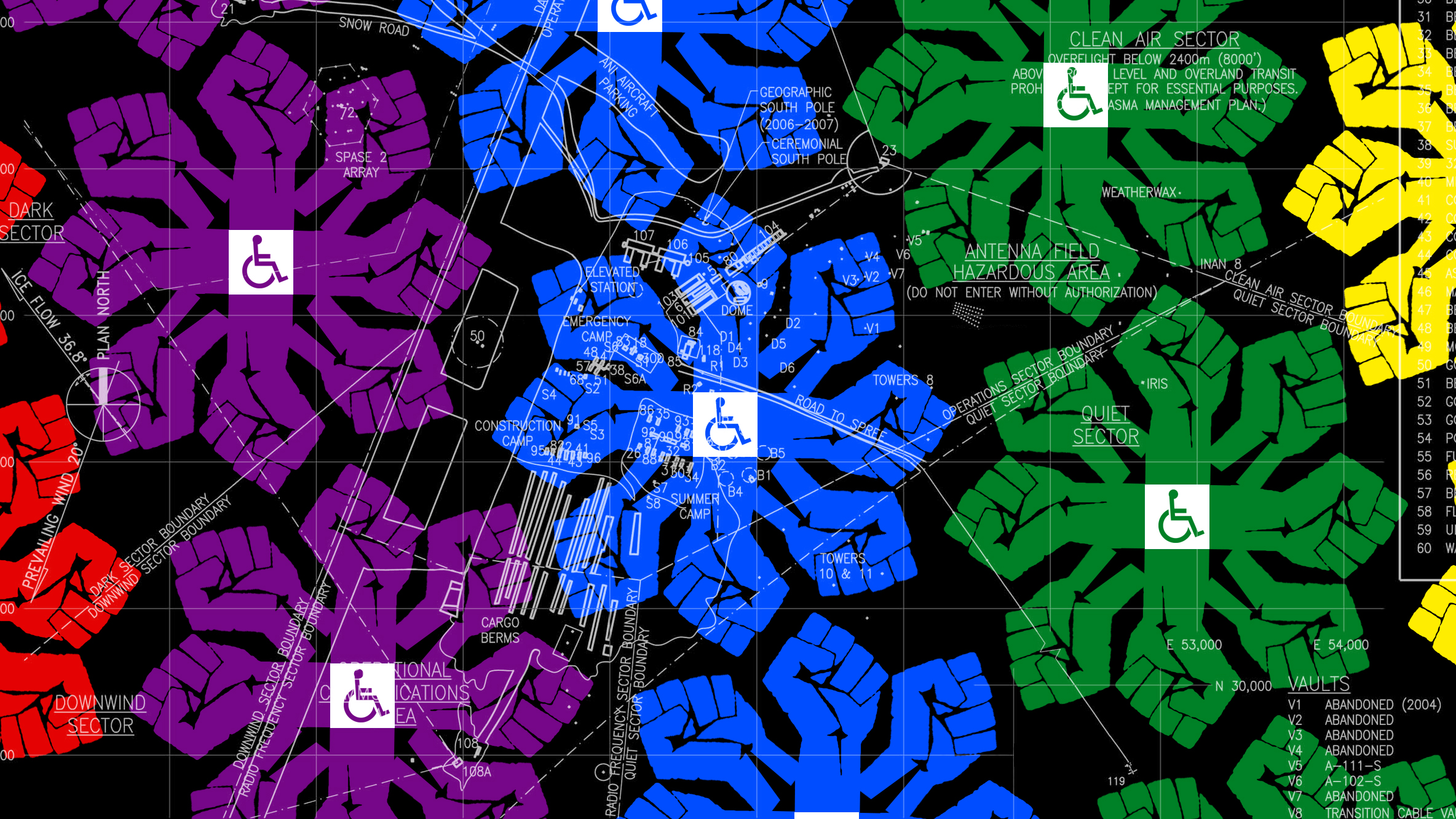

I also learned that disability does not inhere in a bodymind but is encountered in the social world that judges so many deficient and defective. This “social model” of disability was an early challenge to the “medical model,” which understands disability in diagnostic terms. My medical diagnosis is quadriplegia, or significant paralysis in all four limbs, which calls for treatment under a doctor’s care. I continue to see my physiatrist, who has overseen my rehabilitation since my first day in the ICU of Hartford hospital. That’s all very well and good, but I am dis/abled not when I am sitting in the doctor’s office, but when I am blocked by the built environment I encounter. Disability is not in me. Disablement happens to me.

A world of steps blocks all wheelchairs or scooters. Take a look around and you will see how often massive flights of stairs are used to demonstrate the elevated status of an institution, like the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Run up and down those stairs enough times and you’ll be ready to triumph, like Rocky Balboa. The obverse is equally true. Can’t climb the stairs? You’ll never be a champion. Instead, signs direct me around to a decidedly unceremonious back door. This access is mandated by the Americans with Disability Act, a federal law passed in 1990 after years of political activism on the part of disabled people. In one of the most visually dramatic demonstrations, some activists transferred out of their wheelchairs at the foot of the many steps running up to the US Capitol and dragged themselves up as best they could.

Social disablement and the work opening out from that foundational concept create real problems of nomination. Calling myself disabled is, in fact, inaccurate, given that the deficit is in the built environment, not me. Yet the fundamental distinction between ability and disability is so profound that I have not yet discovered an adequate way to speak or write about myself without reproducing the logic of that hierarchical binary. Other descriptive terms—“incapacitated,” “unfit,” “injured,” “impaired,” “undone”—are also marked by prefixes negating the positive state. Those prefixes have occasioned me some real trouble as I have searched for ways to represent the life that I’m now living, and the bodymind I have no choice but to accept.

“Disability” has become many things since the development of the social model in the early days of disability studies—an identity to be claimed (disabled and proud), a civil-rights movement (what do we want/ADA/when do we want it/now), a rhetorical prosthesis that props up narratives (the little lame dolls’ dressmaker, Jenny Wren, in Dickens’s novel Our Mutual Friend), a canary in the mine of neoliberal politics (most vulnerable to cuts in public services), a wrench in the works of capitalism (unproductive bodies that don’t labor). Disability has become a starting point from which to consider whose capacities are rewarded and enhanced, whose neglected and exploited—an approach that articulates with other critical analyses of structural injustices. All life is precarious, but some lives are exponentially more threatened than others.

None of these approaches directly address the challenge of living with pain or the interminable work of mourning the loss of an able body. I’m not surprised that so little writing in disability studies concentrates on pain or mourning. These are affective states that return attention to an individual bodymind, which contravenes the basic premise of the field. Pain is notoriously complex and resistant to medical treatment and also presents the sufferer with the problem of zero-degree significance, since you can only describe pain by way of simile or metaphor. The pain of diverticulitis is like broken glass in my gut, a friend told me. Chronic neuropathic pain, let loose on me by my damaged central nervous system, sparks in my synapses, buzzing and burning. My tissues are suffused with billions of points of light, each one a tiny shock of electricity.

The emoticons known as the numerical “pain scale” that you’ve encountered in your doctor’s office—starting at 0, “no hurt,” showing a round face with the line drawing of a broad smile and happy eyebrows, and ascending to 10, “hurts as much as you can imagine,” showing a sharply downturned mouth and teardrops falling from schematically squinting eyes—are just a visual instance of this dilemma. This scale opens every medical encounter, as a nurse takes your vital signs and asks you to rank your pain. Your responses can chart pain over time, but the quantitative data are plagued by one outstanding difficulty: there is no common denominator. Your pain is invisible and intangible to others, hard to describe and hard to manage. The knowledge produced by the pain chart makes you a single datum incapable of leveraging a broader understanding of the phenomenon. No wonder scholars in disability studies work around the body in pain or attribute the source of the pain to the exclusions every disabled person has encountered.

Like physical pain, the mental pain of mourning is also singular, yours alone. I have discovered that my attachment to life is attenuated and is likely to remain so as my physical difficulties increase with aging. I am glad, then, that memories of my life before the accident are vital enough to return me in my imagination to those earlier days. My pleasures were so embodied, and I was so alive to my pleasure! I can still feel kayaking—how I initiated the force of each paddle stroke by driving from my feet through the torque of my hips and torso, and the simultaneous push and pull of my arms. How I kept my balance and the deep, absorbing satisfaction of physical effort and skill. These memories that afford pleasure can, of course, quickly sharpen into the pain of loss. Yet the pleasure is real, and I’m committed to memory. I carry with me the body I once was, and I will not lay my burden down, because to be disburdened of the past would leave me utterly bereft.

To some working in the field of disability studies or active in the movement, public discussions of grief and pain are unwise. After I presented my work at a conference, one of the participants responded by raising the very real political dangers of associating grief with disability. What you are saying will be held against us. Okay, yes, your dilemma is real, but once we start talking about ourselves as grieving, pity will be the response. Even exploring physical pain makes us vulnerable to the idea that the first thing we want is a cure. In a world in which bodyminds are so relentlessly sorted by those powerful negative prefixes, pity is the nearly universal response to disability.

And so, activists and scholars alike have turned to pride as a counter to condescension. Pride announces a fundamental rethinking of received ideas about disability. Being differently embodied, scholars argue, gives you a conceptual lever forceful enough to displace the fixed negativity of dis/ability. “Crip pride” breaks decisively, and derisively, with the idea that disability is by definition in need of a cure. You announce not only that disabled bodyminds are by no means inferior, but also that anomalous embodiment can afford a singular, necessary apprehension of the world. Sexual pleasures, for instance, unfold in extended time and may require forethought and planning for their execution and enjoyment. The expansive understanding of human sexuality afforded by disability picks up certain aspects of queer sexuality—both are life-affirming in their perverse indifference to phallic normality.

But I believe it’s equally important to think about negative feelings like shame, loneliness, failure, and despair, as many significant works in the field of queer studies have done. The scholar Eve Sedgwick identified shame as an early and formative human experience, felt with particular intensity by children who know they are queerly different, and others have extended her ideas in the decades since. Queer critique argues that unseemly feelings affect body and mind together.

I know that being suddenly paralyzed by an accident at age fifty is different from living from birth as a bodymind marked by so-called incapacity and very real disablement. There are so many ways to become disabled over the course of a lifetime—injury, illness, the sudden manifestation of a genetic anomaly, or the infirmities of age. Disability, like queerness, is a messy, variable, and complex category because the physical and mental conditions that become disabling are many and incommensurate. The early activists to whom I owe so much understood that unifying this disparate number was one of the crucial tasks of organizing. Disability pride is a necessary affirmation of easily disregarded and discarded lives, and of enormous political value.

Disability studies, however, is an intellectual undertaking that I think could productively disaggregate that unity. Disabled people would be better off if we could think through our differences, which we could do without sacrificing our political commitments. There is a drumming relentlessness in the call to pride, and I imagine there are others who don’t feel addressed.

I understand the power of pride. Given how the world has changed for LGBT people, I can understand why some activists focused on disability aspire to the apparent successes of the gay-liberation movement. In 1976, the seventy-five or so marchers in Rhode Island’s first gay-liberation parade gathered in front of the cathedral in Providence, after winning a court battle required to simply secure a permit. We marched through a mostly deserted downtown, our chants echoing off the empty buildings. Say it loud / gay and proud! Around fifteen people in our little crowd marched with bags over their heads, fearful of losing their jobs in the state government or as teachers in the public schools. Forty years later, the paper bags are gone, and most people no longer fear being fired if their employer finds out they’re gay. You could argue that gay pride pushed this political transformation, and you wouldn’t be wrong.

But the NYC extravaganza now known simply as Pride will, nonetheless, step off without me. I’ll march, rally, or demonstrate, but I won’t parade, not even with marching bands and fabulous floats and politicians carrying rainbow flags, while millions (literally!) crowd the sidewalks and applaud. No, the struggle I joined was for gay liberation. Gay pride was a means to that end, not an end in itself. I marched for sexual freedom, a still-unrealized hope of rethinking how people might organize their affective lives, their households, their politics. The festival of Pride is fun, a celebration of civil rights that now allow some gay people to shelter under the law. Yes, our marriages have federal recognition, but the law offers cold comfort to many others. Do you know that Lawrence, the Supreme Court case famous for striking down sodomy laws and “legalizing” homosexuality, turns on the question of privacy? You can actively enjoy homosex—behind closed doors. Woe betide you if you are having sex in the car. Or if you don’t have a home and are living on the streets. Pride will then be of precious little help.

I am not proud; I’m angry. I want to live my life freed of barriers to mobility, freed of anxieties about capacities, and I want that freedom for everyone. Sustained by grief, and carrying with me in memory the body that I once was, I want radical changes. Why not imagine, and then demand, universal access everywhere? I’m ready to march with others insisting on universal access, the universal design necessary for that access, and a revolutionary respect for all bodyminds. I need curb cuts everywhere now, and subway elevators that always work—as does anyone pushing a stroller or grocery cart. In fact, everybody surges through those curb cuts every time the walk light flashes at an intersection in Manhattan. No one is impeded; all have access. That’s why it’s called universal design.

The radical claim of militancy and mourning is that you are not required to set aside the messy, dark, grieving, perverse, incapacitated, angry, or shameful parts of yourself to be admitted to the public world. Even if universal design should magically appear everywhere and signal a sea change in public understanding of what it means to be disabled, that fact would not touch the neurological pain lighting up my body, or my balky bowels that move only when highly disciplined with laxatives and enemas, or counteract the loss of endless bodily pleasures. Not even that truly radical transformation would assuage my grief for the bodymind I was, thinking about my cadence as I crested that hill. Remember how that felt.