Two people were standing on the steps. A man and a woman. The woman—bony and tall, her face already red with cold—had been here before.

“Hello, Karin,” she said, and moved closer to the doorway.

When she opened her mouth, a chipped front tooth peeked out. She’d noticed it the first time she had stopped by; it was one of those things a normal person would have fixed right away. The man standing behind her was fogging his glasses with each breath. Both were wearing winter jackets with large hoods. Their compact car was parked in the driveway.

She didn’t say a word.

Her cheeks flamed with an unwelcome blush.

She fought the urge to slam the door in their faces.

“May we come in?” the woman said, and lowered her eyes, as if the imposition truly pained her, because she had so much respect for personal privacy.

They used a certain tone, as if they didn’t quite believe you understood them, and employed a false, ingratiating manner. You had to be sure not to fall for it. She wondered where they’d learned it, or if only people who were naturals—promising actors like these two—found work in this field.

Dream drooled on her wrist, and she noticed that she was holding her out like a shield.

The woman took another step forward.

The man stayed on the stairs. He removed his glasses and wiped them with a cloth.

The woman glanced expectantly at her colleague, and then at her. “May we come in for a chat, Karin?”

She mumbled something in reply, pushed open the door, watched herself step aside and grant them entry.

Their jackets rustled.

They hung them on the hooks above the paper bag stuffed with mail, letters they or someone they worked with had probably signed. Neither of them seemed to notice it. They took off their shoes, exposing their socks; his had a hole by one big toe.

And then they moved deeper inside the house.

With quiet purpose. Greedily.

Even if this was a purely routine call, they approached their plunder with an ill-concealed, smoldering excitement. They stared in hot silence through her dirty windows, drinking in the view. Her view. They turned around and stared at the fireplace; its little white remote control was on the coffee table even though the gas had run out and it could no longer be lit. They looked at the painting on the far wall, her painting, the one she’d assumed was stolen when John gave it to her.

They had already sent around an appraiser, who’d gone through everything.

She watched them.

“Do you mind if we sit here?” the woman asked, holding a backpack that bore the logo of the Swedish Economic Crime Authority.

She nodded and tried to collect herself, gather her thoughts.

They sat down on the same sofa.

She heard herself ask if they wanted coffee.

Struggling to sound neutral. Polite, but not overly so.

“Sure,” the woman said, surprised. “Why not?” She paused. Swallowed.

“That would be lovely,” she continued. “If it’s no trouble.”

The woman looked at Dream, who was sitting on the floor with the cable.

She shook her head and wearily echoed the woman’s words, in a tone bordering on snide that she knew she had to temper.

“No, it’s no trouble at all.”

She didn’t want to seem defiant. She didn’t want to show that what they said or did affected her in any way. She was supposed to be indifferent.

As cold as the icy slurry outside.

She turned on the coffee machine, which she’d filled with the last of his coffee beans just a few days before, and the sound of it drowned out everything else. She brewed two cups, relieved neither of them asked for milk because she didn’t have any and hadn’t for a long time, relieved that they’d stopped nosing around. But now their eyes were on her.

The gray light made their contours dark and shadowy.

She couldn’t believe they were here.

She rummaged in the kitchen and found a package of cookies that had been in the cupboard since whenever Anna had brought them over. She arranged them on a Japanese dish and put the dish and the mugs on a tray, which she carried over and placed on the coffee table. Even though she saw that they saw the perfection in this act, their presence made her feel like a child.

She’d moved around the kitchen as if it weren’t really hers, and they’d tracked her every move.

She should probably get dressed, but screw it. Her fucking robe, his robe, this dirty robe where traces of his skin mingled with her breast milk and their daughter’s feces, had cost more than everything they were wearing put together.

But they knew that.

They knew about each one of her possessions. Perhaps not these two, specifically, but someone somewhere knew. They had tabs on every last krona.

Everything had been documented, every one of her purchases, each step she’d taken, or so it seemed. Pictures of her on airplanes and at the watchmaker’s shop. Tickets to Thailand and Brazil, gym memberships, dermatologists, timepieces, jewelry, cars, boats. The dog and the horse each had its own column.

They were worse than the cops.

They were the cops, John had said. The police, the Enforcement Authority, the Tax Agency, the Social Insurance Agency, the Economic Crime Authority, the Prosecution Authority, Customs, the Migration Agency. The government agencies all worked together and shared information about the people on the list.

When he had realized he was one of those people, he’d read everything he could get his hands on about civil forfeiture, and she waited for him to say, It’s only money. They can take what they want; there’s more on the way.

But he never did.

The woman stirred her coffee with a spoon.

“Karin, sit down,” she said.

She sat on the sofa across from them.

The man reached for a cookie, stuffed it into his mouth, and then licked the crumbs off his lips. She could hear him chewing and swallowing, and the scent of coffee tore into her. She should have sat down to begin with, shouldn’t have allowed them to see that she didn’t want to sit.

To get the words out, she cleared her throat.

“What’s this about?” she said.

“You know very well what this is about. We’re here about the distraint of goods.”

The woman gave her a worried look and pulled a plastic folder from her backpack. She slipped a page out and handed it to her.

She took it.

Looked at Dream and her cable and then at the paper, even though she didn’t want to.

And put it on the table.

Using two fingers, the woman pushed it closer to her.

“Has an opportunity arisen for you to pay off your debts?” she asked.

“I don’t have any debts.”

The woman stared at her.

“Well, yes, in fact you do. Since this investigation was carried out, we’ve determined that you do. This here is your debt to the Tax Agency, which has been given to us for collection. This you already know.” She wiped a drop of coffee from her mouth. “After the investigation was concluded, you were informed of the outcome and we’ve since called and sent letters… We’ve tried to reach you. And, of course, this isn’t my first visit.”

The woman paused. When she opened her mouth again, she sounded more sympathetic.

“And because we’ve spoken before, I wanted to come by in person, before the eviction, to make sure you’re clear on what’s about to happen.”

“Sure.”

It was all she could say.

She could hear herself breathing.

A sparrow landed on the terrace railing.

It pecked at the wood.

The woman’s eyes were wide open, compassionate.

“The assets will be seized in order to cover your outstanding tax debt. This has always been in the cards. That decision was made long ago, but I think it’s important you understand, really understand, Karin, what’s about to happen.”

“All right, then.”

She could still hear herself breathing.

Dream slapped the floor with the cable.

She noticed that the fog had dissipated and the wind was tearing through the dry reeds. A black-throated loon flew over the lake.

There was an unfamiliar spot on the window, sticky and whitish, that she hadn’t noticed before. She stared at the spot for a while, until she felt compelled to turn her attention back to the woman.

“Your earnings and expenditures from the past years have been assessed, your travels and the ownership of, among other things, this house. Which is mortgage-free.”

She watched how the woman’s face moved as she spoke. The pores along the sides of her nose were enlarged, some clogged.

Reluctantly, she met her gaze.

“And the taxable liquid assets have been assessed, but you know that. You’ve also been referred to the Tax Agency, but you have yet to make a payment.”

She looked at the woman, at the paper on the table, and felt the room shift. It fell away behind her, the floor opened up, the walls slid apart, she looked at Dream.

“When will it happen?” she asked.

“Well, the requisition is scheduled for next week, so that means, it’ll be, ah, in nine days. And at that time we’ll also seize a vehicle, meaning your car… The one parked outside, correct?”

“I guess.”

The large black-and-white bird rose in the sky, its wings outstretched. One of them seemed to be pointing straight up into the heavens. The bulletproof glass didn’t let in any noise, but she imagined the bird’s cry pulsing over the lake, over everything on the other side of the windowpane.

“Where am I supposed to go?”

She hadn’t meant to say that out loud.

As if to underscore the humiliation, the woman didn’t respond. Something surged from the void within.

Nausea.

The child started crying and she went over and lifted her up, rocking her and pressing her against her chest, against her pounding heart, and then walked across the floor.

If they were speaking, she couldn’t hear them.

She gazed through the window at the lake. She searched for the pair of swans and spotted them in a thicket of reeds, nuzzling each other, their heads tucked into their wings, the snow close to their feathers, which were waxy and not quite white.

She bounced Dream on her hip and walked back to them.

“I thought you might have questions,” said the woman. “And if there’s anything I can’t answer, Göran here can help.” She gestured toward the man. He set his coffee cup down and cleared his throat.

She didn’t have any, but he jumped in anyway.

“We follow the money,” he said. He seemed to think he was introducing her to a new concept.

“I’m sure you know that’s how we fight organized crime nowadays. It reduces the incentive for this type of serious crime that creates so many problems. For everybody. The kind no one wants in a modern society.”

She nodded and looked at him. An administrator at the Enforcement Authority. Sitting there in his plaid shirt and looking at her as if he fancied himself some sort of hero.

She noticed herself bouncing Dream far too vigorously. Took a breath and stared at the floor, trying to calm down. She studied the grain on the parquet and listened to the man drone on about how a locksmith would pay her a visit when the time came, about the storage of furniture and how certain personal items—food and clothing and dirty laundry—would be handled, if anything like that was left in the house.

“It’s best if you clear everything out yourself,” he said. “Now. Before the eviction. And do the cleaning. If you don’t want to incur any additional costs.”

He was speaking faster all of a sudden.

When she leaned toward him, she noticed he had a smell, and that smell was fear. So, she wasn’t just anybody after all.

She stood in front of him.

He fell silent.

“Is that it?” she asked, raising her voice over Dream’s, who had begun to cry.

The woman nodded.

“Yes, unless you—”

“Then you can show yourselves out.”

“Do you have anywhere to go?” the woman asked as she got up to leave.

She didn’t reply.

“Social Services will be looped in too, you know.”

As she ascended the stairs, she heard the woman say: “You’re not alone, Karin. Trust me, there are lots of girls in your situation.”

She stopped.

“I doubt that very much,” she said. “I don’t think you have any idea what you’re talking about.”

While they were still watching, she went into the bedroom and closed the door. Rage overpowered her—an iron hand clamping her head and squeezing her mind in its vise until only a slim ray of light and reality remained.

She took a deep breath.

Dream quieted down as soon as her head met the bed. The baby was exhausted. She lay next to her; placed a hand on her soft, hot body; and listened. Beyond her own beating heart, she heard the front door slam, a car start and drive off.

The air in the bedroom was stuffy. The bed felt damp. Dried pools of breast milk and urine, patches of drool, and globs of spit-up splotched the champagne-colored satin sheets. On both of the nightstands and on the floor lay empty packets of Tylenol, tubes of Voltaren, and old nursing pads. Dirty towels and crumpled wet wipes were strewn among glasses and bowls crusted with leftovers.

Her arm was wrapped around Dream.

She stared at the ceiling.

The little one woke up, but fell right back asleep; she let go of her, rolled over, and tried to picture John, but it took her a moment.

This was a recent development. She’d first noticed it on New Year’s Eve. Dream was sick and had finally drifted off and she wanted to treat herself by fantasizing about him, but his face was hazy.

The space around his jaw seemed to have been erased, as if she couldn’t remember its contours or what his stubble looked like.

She opened the drawer on the nightstand and took out the old cell phone. She dialed her voice mail and covered the speaker to block out that loathsome automated female voice. She hated it because it had become a witness. When it was done, John’s voice materialized:

“Hey you. Whatcha doin’?”

A rustling sound. Maybe he was scratching under his collar.

“So, I was thinking. How ’bout we go kayaking this weekend? I realized… Well. I gotta spend some time outside. Okay. Mwah.”

The beep that signaled the end of the voice mail cut into her. Then came another recording, filled only with the sound of breathing, static, and a click. Followed by a beep and then a shorter message:

“Hey, bring my sunglasses, will you? They’re in the hall.”

She sat in the large bed clutching the phone and crying, letting his voice consume her. With each syllable, a room opened up containing everything he was to her and everything she believed she’d been to him. Their entire life as a couple seemed to be encapsulated in each of his ordinary words, in how he said them and strung them together, how they hung there between him and her.

She buried her face in the bedding, felt her mouth open, and heard herself scream into the fabric and the feather down. She soaked the sheets around her and tensed her body so much that her legs lifted off the bed. She cried and cried until her cries were as dry as shouts. Enough already, she thought, this must be the last of it. And behind that thought: there was no end.

She sat up.

Blew her nose and lit a cigarette she’d found in the bed; the nicotine reconstituted her. She looked out the window, where the snowy crowns of two pine trees swayed against the murky sky, and hoped that Dream wouldn’t wake to find her crying.

That’s how it is. At first, you’re cautious, bearing the terrible weight of having someone else’s life in your hands and of bringing a child into a family like this. And then you relax. It doesn’t matter as much anymore. What will be will be. The child is at your mercy. You and the child are one and the same.

Fast asleep, Dream pursed her lips and put her hands by her head.

She closed her eyes and let her thoughts churn.

It was time. She had to get going.

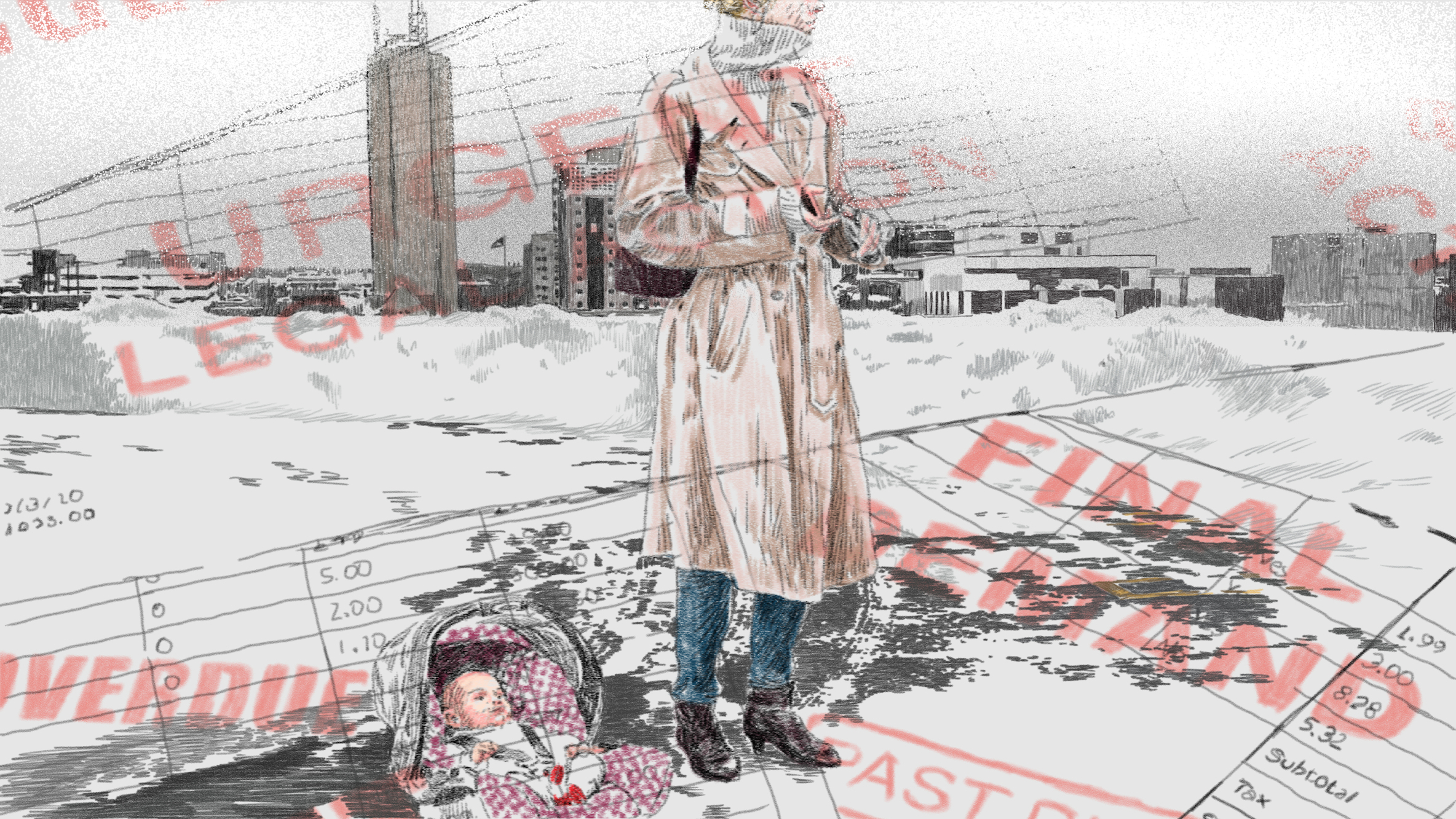

The parking lot was covered with snow, ice, and sand that had been strewn to make it less slippery. The towering white high-rises ahead were like an island in a suburban sea of endless nothing: highways, viaducts, apartment complexes. The snow obscured remnants of mountains and forests that had given way to civilization.

Soon darkness would fall. The sky was heavy with the promise of snow. A heightened gray, the color of the asphalt, patches of which showed through.

The gas tank was almost empty.

She gingerly closed the car door and walked around. Her hair was still damp and a few strands froze to her face. They crunched when she brushed them to the side and tucked her hair into her jacket.

She was on her own and had nothing. Nothing but a child she was obliged to care for. Her face burned with the memory of each warning she’d received.

Those thoughts were hard to face.

Everybody had said it would turn out like this.

Of course, she too had predicted that she’d end up alone. She had thought of it often, in fact. The nightmares she’d had about his body, his beating heart, his face—crushed. He’d take a seat at the kitchen island with his newspaper and turn to her, his face a black bloody mess.

She’d been terrified of losing him. At times bracing herself, at times forcing it out of her mind. But she hadn’t expected to lose everything else along with him.

Dream was asleep in the backseat with her fleece hood pulled over her eyes. She succeeded in stuffing Dream’s hands into her mitten cuffs, unfastening the seat belt, and taking out the car seat without waking her up. As she gripped the handle she thought she could feel his hand holding it too: his warm palm, his fingers and fingertips, their touch as real as Dream’s had been just now.

He bought the car seat.

It was the only thing he’d had a chance to buy.

She hung it on her forearm even though the baby made it too heavy to carry that way. It would leave a bruise.

After she’d locked the car and put the key in her pocket, she paused. There was no one else around. She clutched her jacket at the collar and started to walk, noticing that she was tensing her upper body in an attempt to fend off the cold or perhaps force it into submission.

Her ankle boots had slim heels and shiny soles. The dark ice on the ground was dusted with snow. She stepped onto the road, telling herself not to slip, and then slipped.

She managed to lift the car seat into the air before she lost her grip on it, fell, and let it land on her body. She shrieked.

And then it was as quiet as before.

Tears welled in her eyes.

She got to her feet and brushed herself off, shaking.

Her cheeks burned. Pain shot out from her tailbone.

Dream was screaming.

She continued along the icy asphalt, trying to rock the baby while taking small steps—avoiding icy patches and puddles, head down, and holding the car seat so the wind was out of Dream’s face.

This nothing place.

A few streetlights lined the walkway leading out of the parking lot. A park bench and a low post from what was once a trash can but was now just charred remains. From the stairs, you could see the bus stop and the back of a shopping center; its roof was covered in graffiti and full of trash that teenagers and homeless people had left behind. In the distance, the highway was a river flowing away from her. Other islands of high-rise apartments.

She held on to the cold railing, and her bare palm froze to it. When she’d reached the top of the stairs, she moved the car seat farther down her arm and continued along the path.

She noticed herself trembling.

Dream was quietly letting herself be rocked.

She entered the courtyard. Two groups of young men were hanging around outside the buildings; they circled each other like amoebas in the dark. Heated conversation, cell phones glowing, spitting, and throwing punches and kicks. Clouds of breath floated between them. She walked by, eyes fixed to the ground; she was just a mother out with her baby, nothing more, and yet their laughter and banter stopped as she passed.

They mumbled to each other, and then shouted after her.

She didn’t look back; she kept going. Trying to step only where there would be friction—a piece of gravel, frozen or packed snow, bare asphalt. During her fall, she’d broken a nail. Watery blood rimmed the break and she pressed her thumb against it.

In the tiled corridor leading to the building’s entrance a man in a baggy leather jacket and gabardine trousers was smoking, jumping in place, and kicking a small mound of snow. He nodded in her direction when she went by, but she ignored him. When she walked through the unlocked door, she was surprised he’d gone outside for a cigarette; the stairwell stank of smoke.

Dream had freed her hand from one mitten and was holding on to the edge of the car seat, fast asleep. Huddled together on the stairs next to the elevator were two whispering girls. She said hello and felt them watching her as she got into the elevator. There was only one apartment on the top floor. Alex’s penthouse. A nasty dump of a penthouse, but whatever.

The first thing she noticed was that he’d installed a security system and a video intercom at the front door. She set the car seat down on the landing and looked at the sleeping creature, her little mouth fixed in a determined line.

She hadn’t been here since it happened.

She couldn’t stop staring at the sturdy steel frame around the door. For a moment, she stood perfectly still.

Even the reinforcement on the door was made of polished steel. The mail slot was sealed shut with large bolts, and there was a faint mark where the old doorbell had once been, a hole that had been spackled but not painted over.

She stood up straighter and tensed her lips out of habit. She rang the new bell, assuming her face would instantly appear on a screen somewhere inside. Waited, listened to the locks rolling into place, and when the door opened she couldn’t remember if she’d seen the guy before. He was probably one of the young thugs Alex surrounded himself with nowadays, this kid with bad skin and tube socks who was looking at her and Dream, not saying a word.

Maybe he didn’t know who she was.

She probably wasn’t special anymore.

The air in the apartment was thick with weed. He showed them in and vanished. Therese’s voice came from one of the rooms, cracking, raspy.

And then there she was, right in front of her.

How odd. After all the time that had gone by, the many days without phone calls, without seeing each other, she’d almost expected a stranger. But it was just Therese, lounging around. The sweet, familiar scent of her black hair. She remembered exactly how it felt when they were skin to skin.

And yet, here they were. Estranged.

Therese just sat there, didn’t even look up.

She’d never really considered how different they were. As she looked at Therese lazing on Alex’s leather sofa, watching a television set hung like a painting, she thought about how ironic it was that now, when they weren’t quite so different, they were no longer close.

Therese still hadn’t looked at her, even though she was standing right there. Eyes riveted to the screen, she didn’t seem to want to acknowledge her presence: pies and cakes were being filled and frosted, tasted, glazed with egg whites, and placed in ovens. Without looking over, she greeted her with something that was not quite a wave. “Sorry,” she said. “I don’t feel like getting up.”

Her arms hung limply at her sides; her legs were resting on that dark coffee table Alex had always had. She was barefoot, her slim toes crowned by a French pedicure that looked as soft as her brand-new pink velour tracksuit.

She couldn’t stop staring at Therese, but she didn’t want her voice to betray her when she replied.

“No worries,” she said as she put the car seat on the floor and rocked it gently.

Therese’s hoodie was unzipped, revealing the top of her tattoo.

She had dark circles under her eyes, but her cheekbones seemed higher and her lips were pouty and glossed. Her skin was pale and flecked with pimples and other blemishes that hadn’t been there before, but her face shimmered supernaturally in the dim light of the room. Her nails shone too, and on each hand the letters FUCK were painted in black over a glaring polish.

Empty bottles of Vitaminwater were strewn on the table, along with an ashtray filled with cigarette butts and half-smoked joints. She unfastened Dream’s overalls, fingering the smooth fleece and the small snaps, gazing at her soft, peaceful face. She’d been at Dream’s side since the day she was born. How would it feel to leave her here?

She slipped off the child’s booties and her beanie, so she could keep sleeping without getting too hot.

She took a seat on the sofa.

Finally, Therese looked at her.

Her eyes were dull and dark. The gleam they’d had when they were friends wasn’t there anymore. She’d been missing it for a long time, but now she realized she had developed a sense of ownership over it; it was like a lost possession.

“Want anything?” Therese asked, glancing at Dream, who was sleeping with her mouth wide open. “I’m going to have a Vitaminwater. Okay? Can you drink that?”

“Yes.”

“Nothing for her?”

“No.”

Therese turned around without getting up and shouted into the dark hall: “Hey!”

No answer.

“Dumbass.”

She turned again and shouted.

“Stop jerking off, you fucking retard!”

Dream twitched in the car seat and flung out her arms as if she were falling and then fell right back asleep.

Therese sighed.

“I’ll get them,” she said, and Therese nodded listlessly.

She got up and walked down the hall that led through the rest of the apartment to the kitchen. The walls, covered with ingrain wallpaper, were otherwise bare and marred with dirt and black scuffs. The rooms she passed seemed desolate. In a couple, she glimpsed boxes and cartons piled on top of each other, mattresses on the floor that must have been put there so the guys could crash—boys who arrived at night with their haul and didn’t have anywhere better to be afterward. People who might think of this place as a sort of home.

In the hallway was a large safe on a dolly. She stopped for a closer look: the sleek metal handle, the lock and keypad, steel fibers glinting in the fluorescent lights overhead.

The apartment was silent.

She forced herself to move along, trying not to make a sound so no one would notice she’d stopped by the dolly and get it into their heads that she’d been eyeing the safe.

The kid who’d let her in was nowhere to be seen.

On a table in the kitchen were a few cartons of cigarettes and bundles of ten-kronor scratch-off tickets. The Vitaminwater was in the fridge and she took two bottles. Passing the safe on her way back, she felt queasy. She wondered what Alex was going to do with it and if he’d be home soon.

In the living room, the TV show was interrupted by a commercial break, and Therese turned to her with an expression that might even have been a smile.

“Time to get those tits out!” she said.

“Ugh, I’m so over them.” She sat down and unscrewed the caps off both bottles.

“You shouldn’t be.”

“I’ve missed you.”

Therese replied by running her tongue over her bleached front teeth and her gums, which were slightly inflamed. Therese glanced in Dream’s direction and said:

“I get it. It’s been heavy.”

That was one way of putting it.

She nodded and downed nearly half the bottle in one syrupy gulp. She steeled herself and asked:

“Do you know if Alex owes John anything?”

“Huh?”

She shouldn’t have been so quick to ask. Therese raised her eyebrows and shook her head slowly, as if the question came as such a shock she wanted to be sure she wasn’t dreaming.

“That’s why you’re here?”

“Yeah. I was wondering if there was anything with my name on it.” Therese shook her head again. “But I also came over because I’ve been missing you.”

Therese coughed and singed the filter of the cigarette she was trying to light. The tattoo draped across her chest like a necklace: Non, je ne regrette rien. She looked up at her and exhaled a stream of smoke.

“You’ve got money.”

“No, I don’t.”

It made her uncomfortable to say it out loud.

“What?”

“It’s gone. The money’s gone and nothing is on its way.”

“You don’t have a stash somewhere?”

“No. Well, I don’t know. There might be some somewhere. Understand?”

She got to her feet and pointed at the balcony door, so Therese put on a pair of bunny slippers, ears dragging on the floor. They went to the balcony.

“What’s the matter?”

“I haven’t heard anything and no one’s talked to me, so I’m wondering what you might know.” She was trying to sound cool and collected.

“About what?”

“If there’s anything for me… That’s mine.” She looked down at the people milling around in the courtyard. “I’m surprised no one’s sent anything my way. You know, after all that stuff about having each other’s backs.”

Staring at a crumbly crack running across the concrete floor, Therese gave a brief nod. She smirked and a whistling sound escaped from her mouth.

“Oh honey, I’m sorry,” she said, and made eye contact. “Were you expecting to sit out there in your big, pretty house and wait for someone to drop off a bag of cash?”

“Sure, why not? Everyone’s always going on about how we’re a family.”

Therese looked at her as if she was clueless, as if giving birth had made her lose her mind. Then Therese nodded and asked:

“Why didn’t you talk to me?”

“I’m talking to you now.”

She nodded again and gazed out over the courtyard ringed by the housing projects built as part of the Million Program.

“Why don’t you just sell your house?” she said.

“That was supposed to be the plan, so I didn’t make other arrangements. I was supposed to be able to sell it, but I can’t.” She took out a cigarette from the old packet, lit it, and forced herself to say:

“They’re taking the house.”

“What?”

“Yeah.”

“But it’s your goddamn house. You’re just a regular citizen.”

“They made their calculations. They’re following the money,” she said with a derisive twitch.

“So, if your man or dad or son or whoever is on the list, they could, like, take anything they want?”

“Pretty much. If they’re on the list.”

“I thought that list wasn’t real.”

“Oh, it’s real.”

Therese paused.

“Fuck their fucking list! Fuck it all to hell! Goddamnit!” Therese gripped the balcony railing and kicked the metal fencing so hard it sang. Then she stared into the distance, flicked her cigarette, and whistled through her front teeth. “Fuck!” she exclaimed, slapping the railing. “So then there’s nothing you can fucking do.”

“No. But you never know who’s on the list.”

“I bet Alex knows…”

Darkness had fallen.

“At least he should know,” Therese said, and stubbed out her cigarette.

They went back inside.

She sat on the sofa. Her tailbone ached.

She hid her expression.

“I don’t know how to help you,” Therese said, and it almost sounded as though she enjoyed this role reversal. “Alex, he… I don’t know, it’s up to him. You get that, right?”

She nodded and swallowed. Therese met her eyes. She felt like crying.

“But, come on, the fuck you want me to do!” she hissed.

“I don’t know. Talk to him, maybe? Tell him I’m being left out in the cold?”

She’d never asked anyone for help before, and she had imagined it would take a concerted effort, but as soon as she opened her mouth, something happened. She desperately wanted to tell Therese everything—how lonely she was and how hopeless she felt and how she’d never cut anyone out the way they had done to her.

But she held back.

She’d already been too impatient once.

“All that talk about having each other’s backs. It was just talk, wasn’t it?” she said.

She buried her head in her hands and waited for Therese to put a hand on her shoulder. When she didn’t and nothing else was said, she felt the weight of the air around her. Her heart pounded. So she was alive after all.

When she looked up, Therese seemed to be on a high ledge, staring down at her, taking pleasure in seeing her at the bottom of the ravine.

And she heard herself make another plea:

“I thought you might know if anyone owed John anything.”

“Gawd, Karin. I don’t know! Why would I have any intel? Alex doesn’t fucking talk to me!”

“I just thought that we… know a lot. Even if we’re not supposed to. Right?”

She wasn’t sure how eager Therese was to rekindle their friendship; maybe she didn’t even want to, so she didn’t mention how much their relationship had changed. She didn’t have to; it was right there between them. To distract herself, she took Dream out of the car seat and held her close to rouse her with the scent of milk. She pushed up her sweater, unzipped her dress, and took out one of her breasts. Dream’s lips searched and suctioned themselves to her nipple.

Therese lit another cigarette.

Other than the television, the only sound that could be heard was Dream feeding. One little hand was stuffed behind her back, and the other was gripping her sweater. Every now and then Dream took a break and let go of the sweater, waving her hand and scratching her breast with her small, dirt-rimmed nails.

“I get that you’re having a hard time,” Therese said, in a tone that suggested she was speaking about a natural state of affairs, a situation that no one was accountable for and that, above all, she played no part in.

Therese belonged to Alex now, her life revolved around him, and he determined the conditions of their shared existence.

Dream burped and seemed to be smiling. Milk dribbled from her mouth, as though it were impossible to drink another drop. When she held her upright, her body gurgled. Shuddered. And then there was a bubbling sound. Her diaper had a sour smell.

Without thinking, she handed Dream to Therese, who wrinkled her nose and held her away from her body. Dream laughed and drooled. She took out diapers and wet wipes and the mat, unfolded the diaper bag so it became a bed. She put it on the sofa, placed Dream on top, and unsnapped the snaps on her onesie.

“Why doesn’t it have a zipper?” Therese asked.

“I know, right?”

She began undoing the diaper.

“I guess they think we don’t have anything better to do than deal with these snaps.”

Therese looked pained and fascinated when she saw the yellow mess in the diaper.

“What the hell is she eating?”

She smiled.

Dream clucked when she lifted up her legs so she could wipe her properly, then she folded the wet wipe with one hand and placed it on the diaper. She noticed that Therese couldn’t help looking at the baby’s soft body and her little genitals, a perfect shell of white skin that she still didn’t have a word for.

When she was done, she rolled up the diaper into a package and sealed it with the strip of tape. Then she dressed Dream in her onesie, relieved that it hadn’t been soiled at the back, and propped her up on the sofa with a cushion. She left clean diapers and wet wipes on the table, and from her handbag she took a bottle and a carton of formula.

“Could you watch her for me?” she asked.

Silence.

“Me?” Therese asked.

“Yes.”

“No way!”

“Come on. Of course you can. It’ll only be for a little while. Plus, there’s nobody else who can take her.”

Therese looked at her skeptically.

“Please?”

She sat Dream on Therese’s lap and tore open the carton with her teeth and poured it into the bottle.

“There’s no one else.”

“Where are you going?”

“I have a meeting.”

“Is it a guy?”

“No!”

It was clear that Therese wasn’t going to give in unless she knew exactly what was happening. She sighed and threw open her arms. “I’m meeting Christer, okay!”

“I see.”

Therese nodded suspiciously.

She put Dream’s pacifier on the table and pointed at the charger cable.

“She can play with that,” she said.

The gang was still in the courtyard. A pack of hyenas in black jackets, craning their necks, staring into the darkness. They whistled as she walked by.

She knew what Therese was thinking: Shit happens and it can happen to anyone. And she knew Therese was right. Shit happens to everyone. But she had yet to accept that “everyone” included her.