It may be difficult to recall these days, but there was a time when psychiatry, as a vocation, as a calling, cut quite a heroic figure. You could say, in fact, that the discipline’s founding medium is neither the couch nor the prescription pad. It’s the spectacle of the physician—dispassionate, composed, confident in his refined enlightenment—demanding the emancipation of his patients from their chains. Thus the privileged, almost mythological status of what is arguably the most celebrated image in the history of psychiatry: Tony Robert-Fleury’s 1876 painting of the great Philippe Pinel, newly installed as the chief doctor at the public asylum in Paris, liberating the mad from the iron shackles in which his predecessors had kept them bound.

“So, citizen,” a skeptic challenged him, “are you not mad too, wishing to unchain such animals?” To which Pinel, father of the celebrated traitement moral, later referred to by Sigmund Freud as “that most humane of all revolutions,” replied calmly: “Citizen, I am convinced that these alienated are only so because they are deprived of air and liberty.”

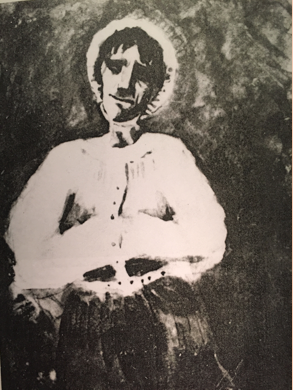

I thought of this famous painting as I encountered, one by one, the lurid photographs accompanying the 2012 Human Rights Watch report Like a Death Sentence. Focused on Ghana, the report seeks to draw attention to the abuses—the chaining of patients’ hands and legs, the denial of food and water, confinement in rooms lacking light and ventilation—inflicted upon the thousands of mentally ill men and women who, over many decades, have come to populate the country’s Pentecostal prayer camps. These secluded healing centers, the report explains, are filling the vacuum opened up by the chronic shortage of proper psychiatric facilities in Ghana. Promising not merely a respite but total deliverance from psychiatric disorders, the prophets and pastors who operate these camps allegedly believe that the ailments they confront are in essence spiritual maladies, demonic “spirits of madness” that must be attacked with vigor. Hence their recourse to forced containment and other aggressive measures. Hence the chains.

And it’s the chains, more than anything else, that have been invoked and reinvoked in the mounting textual and visual archive of denunciations of the camps, the chains that have been made to stand for the more general barbarity, the viciousness, that this particular mode of religiosity is said to traffic in, it’s the chains – these oily, rusty, anachronistic chains – that have become the focal point of humanitarian efforts to persuade the Ghanaian government to criminalize the camps and, if necessary, to arrest and prosecute those who run them.

“If I hadn’t seen it with my own eyes, I wouldn’t have believed that such inhumanity was possible,” declared the director of the disability rights division at Human Rights Watch. Similarly, a New York Times photographer described the photo he took—of a man shackled, naked but for a cloth draped across his left side—as crucial to the task of having to “shock people into caring, if not acting.” The article’s title was telling: “The Chains of Mental Illness in West Africa.”

A number of recent studies have been concerned with the varieties and vicissitudes of humanitarian action. My sense, though, is that before such action becomes conceivable, there is first an ecology of images, of carefully curated appearances, shaking us, beckoning us, not so much haunting as taunting us. Activating certain moral convictions, emotional responses—and decisively foreclosing others.

But if that’s the case, if these images really do have—as they have been said to have—the capacity to speak, then what exactly is it that they’re saying? What is it that we see when we see these images?

We see an absent infrastructure. And what infrastructure we do see looks more like a torture chamber than a clinic or hospital.

We see slavery and the slave trade. If it hasn’t occurred to us on our own, the association is emphatically driven home by numerous references to slavery in the texts attending the photographs: the capture, sale, and exploitation of human bodies for profit on the one hand and the confinement of those considered mentally unstable on the other. Whatever their differences, they’re all collapsed onto a single plane of moral and phenomenological equivalence.

Rarely do we see a face, a pair of eyes. Perhaps it’s a way of respecting the privacy, protecting the dignity or personhood of the man or woman in question. Or maybe their faces are incidental.

Indeed, the monotony of the images seems to be the point: the repetition, the incessant march of what becomes a compendium of barely indistinguishable instances, the stripping away of political logics and institutions and historical antecedents as so much distracting noise.

Yet, as indicated by the gesture to slavery, the images are by no means devoid entirely of historical memory, at least of a certain kind. For this admixture of savagery and superstition—the chains, the callousness, the category mistake of misrecognized etiology—is being forged, we’re told, within the crucible of a distinctive, and distinctly antiquated, spiritual imaginary.

The images, accordingly, come to function as a kind of portal into our collective past, allowing us to bypass the ambiguities and indeterminacies of a far more recent, avowedly medicalized (which is to say, secularized) moment and arrive instead at a time when madness amounted to malefic forces and exorcisms, banishment and exclusion. And also, it need hardly be pointed out, chains and shackles.

Never mind that listening to those whose lives and livelihoods are directly implicated in the prayer camps yields a disconcertingly different picture of what it is they’re doing there. Never mind that when I spoke with him last summer, the prophet who runs one of the largest camps in Ghana described the work they do, first and foremost, as releasing patients from the labels and diagnoses—he provocatively called these the “clinical prophecies”—imposed on them by orthodox medicine. Never mind that the camps are multiplying against the backdrop of a questionable track record of mental health care in the country, beginning with the draconian machinations of colonial psychiatry. Never mind that present-day facilities are overcrowded and understaffed and have been known to administer shock treatment without the use of anesthesia. Never mind that these hospitals are generally perceived—as I heard throughout my time in Ghana—as places where you go to die.

No, we see the images, we read the words, and soon we’re tourists moving back across the threshold, so essential to the self-narration of psychiatry and humanitarianism alike, that separates religious passions from biomedical precision; cruelty from care; otherworldly imaginings from evidence-based interventions; gratuitous, wasteful suffering from the more necessary and beneficial kind.

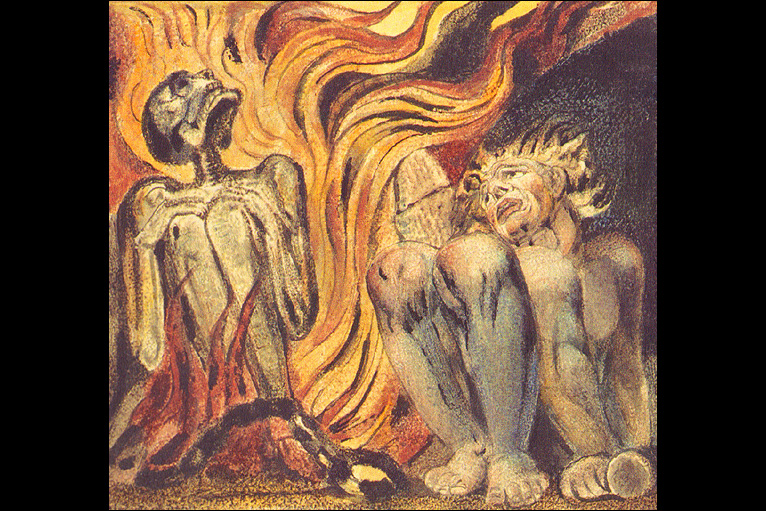

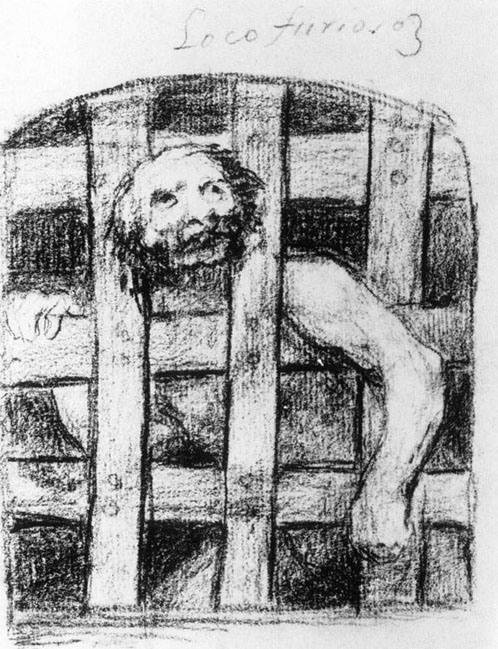

Come with us, you can hear them saying, and before we know it, we’re thrown into the midst of that vast array of sites, meanings, media, and motifs that make up our long and sordid history of visualizing the mad: the madness of the damned in hell, as in the paintings of Blake and Bruegel; madness in the grip of the fever dream of possession; madness exiled and detained; and throughout, inexorably, madness chained.

To be sure, throughout the centuries of seeing the insane, such images have been forced to jostle for position alongside those that posit more naturalistic treatments and explanations. (For example, the once-popular postulation, lampooned in Hieronymus Bosch’s The Extraction of the Stone of Madness, that certain pathologies could be cured by allowing them to be released through a small opening in the skull.) Still, I would argue that the affinities conjured by this photo are of a scarier, more primordial variety.

It’s as if this nightmarish, bygone world, purportedly displaced by the forward march of rationality, has survived on the rural margins of contemporary Africa. As if we’ve touched down in a strange but familiar place whose spiritual ecosystem dictates that mental illness be confronted not as a malady of the body, or indeed the brain, but as a disorder of the soul or spirit. As a problem to be addressed not through medical expertise but through that special form of punishment that stems from this peculiar brand of ignorance.

What’s at stake in this humanitarian iconography, in other words, is not so much madness or mental illness in and of itself. What’s at stake is the injustice, the brutality, of a specific style of managing such afflictions. This calls for a rather different species of response from viewers, and has less to do with staring into the dark abyss of insanity (and/or possession) than with gazing into what Didier Fassin has referred to as the “moral heart” of humanitarianism.

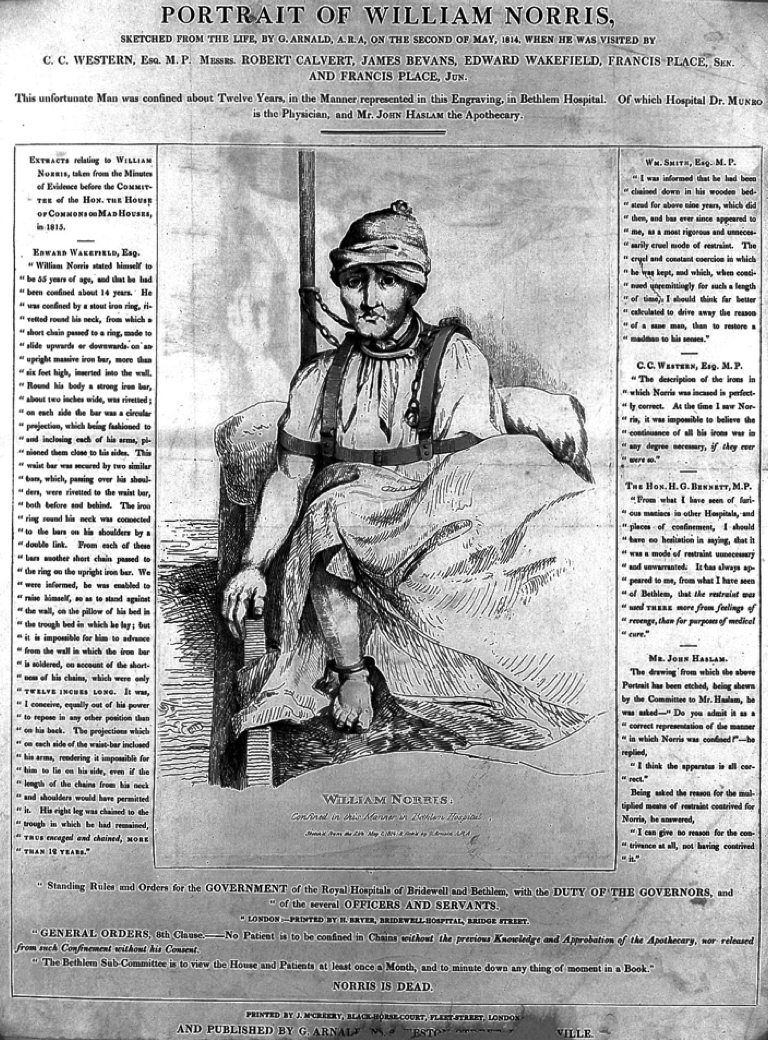

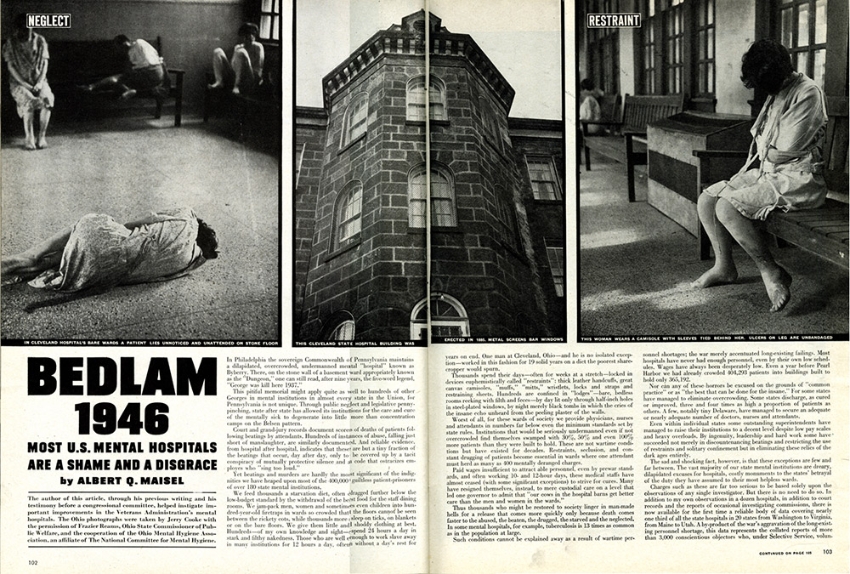

Were we to locate a predecessor for this kind of imagery, we would do well to turn to an artifact such as this:

Commissioned by Edward Wakefield upon his visit to England’s Bethlem Hospital in 1814, the drawing depicts an American seaman, William Norris. According to Wakefield, he had been left languishing in the asylum for more than twelve years. Norris’s portrait, variations on which would appear in numerous newspapers and broadsides across Europe and the United States, can be taken as a signal contribution to a radically emergent way of apprehending the insane. Gone is the quivering, frequently violent symptomatology of madness qua madness; in its place is the unscientific and thus unjustified cruelty of confronting it in this particular fashion.

What’s striking in this disconsolate portrait is how the animality of insanity has been superseded by an appearance of passivity, harmlessness, and, crucially, victimhood. Or, to put it differently, the animal has become a person, a name, a diagnosis—while those responsible for his condition have effectively turned themselves into animals. “A secret,” writes Michel Foucault in his History of Madness, “is revealed. Animality is not to be found in the animal but in its taming.”

Such, we are led to conclude, is the “taming” that’s on display in the photos from the West African prayer camps. And such, some two hundred years ago, was the defining feature of the arguments for reform and, ultimately, the genesis and prodigious growth of the modern asylum. Of course, years later, marshaling the harsher realism of photography and documentary film, yet another group of images would come to light, now disclosing the concentration camp-like conditions of the very institutional antidotes once championed by their humanitarian forebears.

Not that the images from the prayer camps—decontextualized and morally self-assured—have much interest in grappling with this confounding, often tragic record of humanitarian solutions gone awry. The story they relate is a tidier, more palatable one. In the beginning are the chains, they never tire of telling us, and it is from these chains that mental illness must be emancipated.

This brings us back to Philippe Pinel in his Paris hospital. Left undepicted in the iconic renderings of that heroic scene of psychiatry’s inauguration are the various apparatuses into which, as it happens, many of those just-unshackled patients were immediately delivered. There was the tranquilizer and the fixed chair, the rotary chair and the swinging chair; there were iron handcuffs lined with leather, the finger-glove garment, and wicker caskets. Above all, there was that brilliant, progressive new technology particularly favored by Pinel and his forward-thinking colleagues.

Invented in 1770, what made the straitjacket such an irresistible device was not only its less drastic violence upon the flesh. It was also its facility at achieving a more complete mastery over the afflicted and at times resistant patient and, by extension, her otherwise intractable disease. The chains, on this view, were to be discarded less because of their inhumanity than because of their inefficiency. Here, then, at a stroke, in the name of freeing the trapped humanity of the patient, is pain-as-punishment supplanted by pain-as-therapeutics.

Even so, not unlike the shackles it replaced, this invention too would gradually fall out of fashion—as would, in turn, forced lobotomies, and sensory deprivation, and fever therapy, and induced insulin comas, and then the entire creaking, crumbling institutional edifice altogether, until finally, thankfully, we arrived at the neurocentric, non-invasive, psychopharmacological moment in which we find ourselves today.

It’s a moment characterized, among other things, by the increasing offshoring of clinical drug trials; by the transformation of jails and homeless shelters into warehouses for the mentally ill; and by the sovereign omnipresence of the DSM. It’s a moment that has expunged, in rhetoric if not in practice, any trace of the older prerogatives of imposition and control from its therapeutic lexicon. What’s left? Those familiar and taken for granted terms—community care, best practices, clients and consumers instead of patients, and on and on—that now comprise such an established part of mental health care in the global North.

To pretend otherwise would be to fail to register the strange and singular and distinctly contemporary quality of the way my friend, a psychiatrist in Brooklyn, replied when I asked her if she could recommend any literature on the use of antipsychotic meds as chemical restraints.

“Well, for one thing,” she said, “we would never use the language of restraint. We call them functional optimizers.”

In such a purified climate, it seems safe to say, we’re a universe removed from those cruel and clunky chains.

And yet, it may be that even in the most mainstream and well-meaning and medically sanctioned versions of managing mental illness, there’s a darker, more recursive potentiality waiting to be discerned. That the ongoing cost of endeavoring to free the “trapped humanity” of madness remains to be fully counted.

Which is not to imply that there’s a simple answer to all this. It’s to say that no small part of the power and, indeed, appeal of the humanitarian imagery lies in its short-circuiting of our ability to even pose the question.

So, in the spirit of unasked questions, it’s worth ending with another. Suppose these images worked their magic and the men and women in the photographs were suddenly liberated from their chains. What then? What world would be awaiting them?