At the rehab center

late at night when my father

presses the call button,

someone hurries in

and shuts it off, thus maintaining

their quick response rate, but leaves

without helping him pee, he tells me

in a whisper on the best

spring day of the year so far,

of the century: I could have picked

two hundred

million snowdrops on the way in

had I patience

and a doll’s fingers. He’s afraid

of angering the staff and has learned to pee

on himself with dignity. It’s all

in the not-crying. In imagining

he’s a chunk of wind

the next day while his penis

is being washed

and he can’t feel it, just a sock

with a hole in it. I’m afraid

of the future. That I’ll need a gun

to help me out of the jam

of having a body. Is what I’m thinking

while holding his hand, while believing

there’s nothing to be done

about the weight of the night

on his chest except to lift him

and carry him home and give him back

to his own bed to live and die in,

as he and my mother

gave me to the sun all those years ago

to run under and end up here,

not knowing what to do

about the rumor that part of us

goes on after the heart’s last sigh,

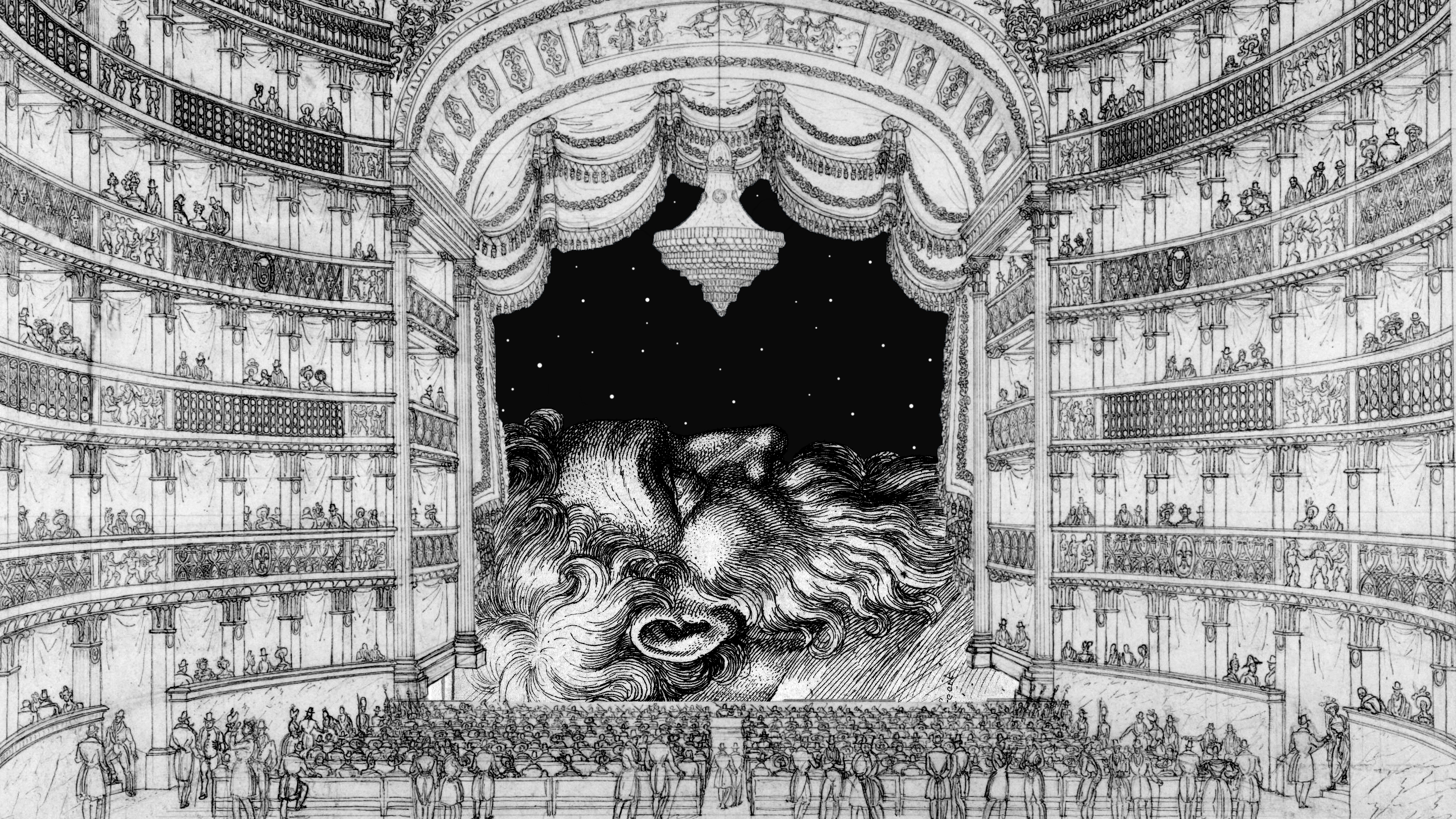

other than applaud the possibility

as I would a woman

standing up from a piano

after the gazelles of her hands

have stopped running, the music over

but not the chance for more music

if we clap enough that she believes

how desperate we are and that only

she can save us.