Photography and language mingle uncomfortably in representations of Europe’s refugee crisis. Ethically shaping the visual and textual discussions around this subject presents a challenge to artists and writers: naming someone a “refugee” or “migrant” has legal implications. The former is protected by the 1951 Refugee Convention and the latter is not. The use of words and metaphors that connote natural disasters and physical threats (i.e., swarm, flood, criminals, cockroaches) affect the hearts and minds of readers. Coupled with alarming headlines, interpretations of photographs can be steered in a direction that stokes fear or outrage. Solmar Sharif, in the epigraph to Look, her first book of poetry, provides the military definition for the titular word: “LOOK: in mine warfare, a period during which a mine circuit is receptive of an influence.” The word “look” embodies both reception and action–the direct object and the verb–and raises the possibility of a realignment of power in the visual realm. So the question remains: How does one represent the refugee crisis?

In their book Foreigner: Migration into Europe 2015–2016, photographer Daniel Castro Garcia and designer Thomas Saxby (the founding partners of John Radcliffe Studio) attempt to address the challenge of representation with intelligence and empathy. The photographs do not resist the power of the camera to objectify, to frame. Instead, the photographer allows the humanity and idiosyncrasy of the subject to exist in blazing contrast with the restrained and restraining photographic gaze. In this way, Castro Garcia’s photographs embody tranquil power and underlying rage, like Solmar Sharif’s interpretation of language in Look.

Foreigner focuses on three different regions of entry for refugees: to Italy from North Africa, to Greece from the Middle East (by way of the Balkans), and the recently evacuated camp in Calais, France, also known as “the Jungle.” Castro Garcia and Saxby intersperse the photographs with profiles of their subjects, maps of the regions in question, and notes on the circumstances under which Castro Garcia gained entry and took his pictures. Attention to contextualization likewise extends to the reading experience: the typeface, binding, paper, and shiny wrapper evoke the visual language of passports, documentation, and emergency blankets–ephemera that take on vital significance in the hands of refugees. The result is a thoughtful document of witnessing, evincing an acknowledgement of the makers’ place of privilege as witnesses and the desire to reframe, educate, and commit to memory the crisis that continues to unfold.

The photographs excerpted below are from the section focusing on Italy and North Africa. The captions, drawn from the book, are written by Castro Garcia.

Lampedusa, Italy, May 2015.

Before I arrived in Lampedusa, Italian authorities had diverted all rescue boats to Sicily, meaning there were no migrants or refugees on the island while I was there. The island has seen its tourism and fishing industries suffer greatly as a result of both the overwhelming numbers of people arriving and, most notably, the number of deaths that have taken place over the last few years in its sea. A local fisherman told me that many men do not want to return to work after boats have capsized, partly out of respect but also because nobody would buy fish that came from the waters around the island.

Lampedusa, Italy, May 2015.

Lampedusa, Italy, May 2015.

Port of Catania, Sicily, Italy, June 2015.

Many migrants and refugees arrived without shoes, and the Italian Red Cross provided socks and a bottle of water for each person within moments of arriving. The medical care was also commendable, with those most vulnerable being the first brought to land, followed by women and children.

Port of Catania, Sicily, Italy, June 2015.

At the Port of Catania in Sicily, I witnessed two separate migrant and refugee landings, and I was immediately impressed by the level of organization and care shown by Italian authorities. In contrast to Lesbos, the Port of Catania had a very calm and effective system for processing people arriving in rescue boats, making sure all were safe and nourished. Those working were able to photograph, register, and fingerprint each person efficiently. Some migrants and refugees refuse to register, as they hope to claim asylum in another European country, wishing to travel to France, Germany, Sweden, or the United Kingdom. Those that do register are transported to the CARA di Mineo, a reception center for asylum seekers.

Port of Catania, Sicily, Italy, June 2015.

Michael, Augusta, Sicily, Italy, June 2015.

The CARA di Mineo reception center is one of the first places that people are taken once they have arrived in Sicily. It is from here that their asylum claims are processed, and often rejected, with the average waiting time for a positive result being eighteen months.

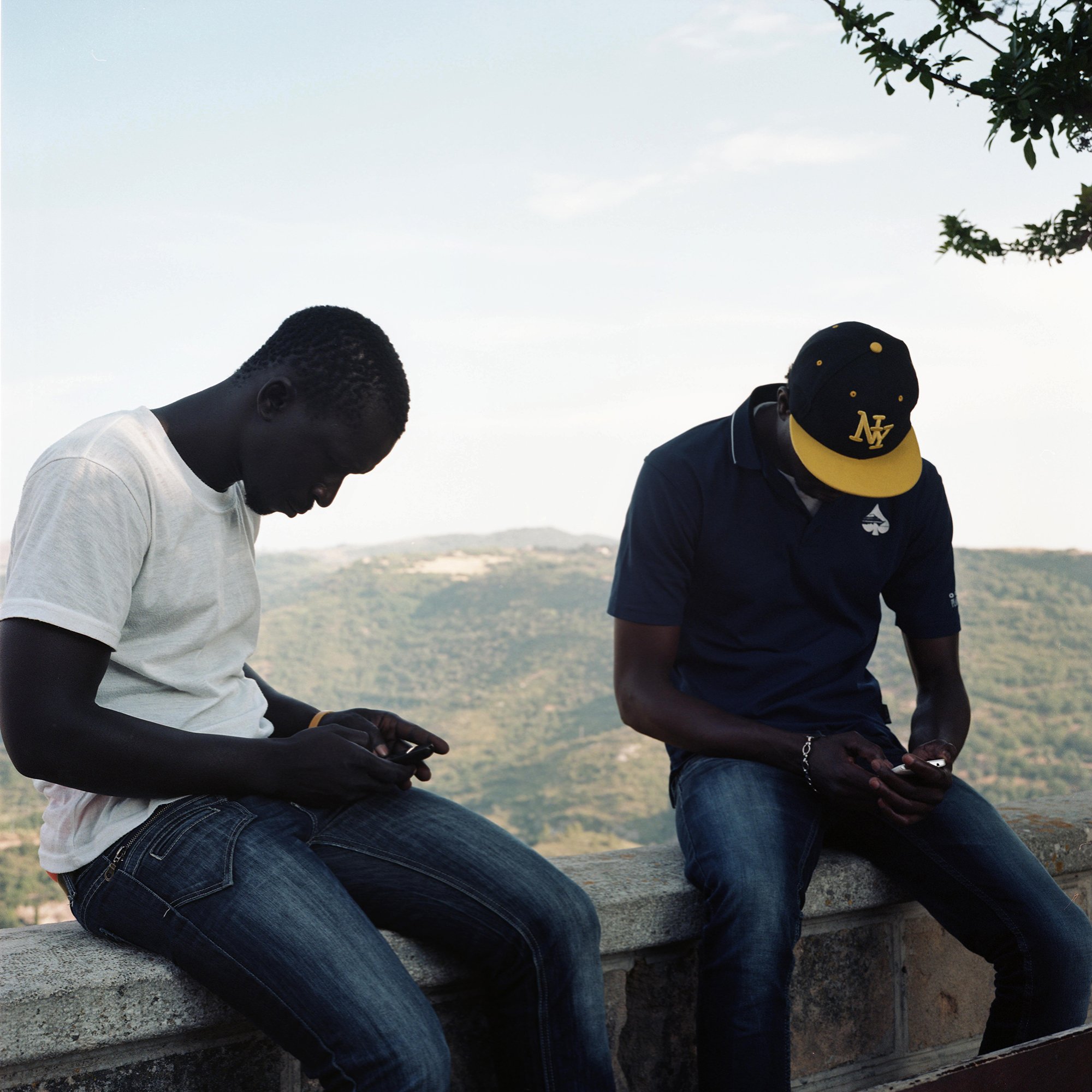

Musa and Omar, Mineo, Sicily, Italy, 2015.

Musa and Omar are from the same village in Gambia and both made the journey to Europe separately. They met at C.A.R.A. di Mineo by chance, having not seen one another for many years. Omar left Gambia first and traveled to Libya. His story highlights the abuses of human rights that are currently rife along the route. Having worked his way through Senegal, Mali, and Burkina Faso, Omar witnessed first hand the horrors of the convoys that travel across the Sahara desert. He spent two weeks on the back of a truck with eighty other people, covered in tarpaulin sheets. Breathing was difficult, and all passengers were severely dehydrated. Four people died and were tossed from the vehicles, their bodies abandoned in the desert. Omar told me that the people traffickers had very little respect for human life, and they would often humiliate and taunt people with their guns.

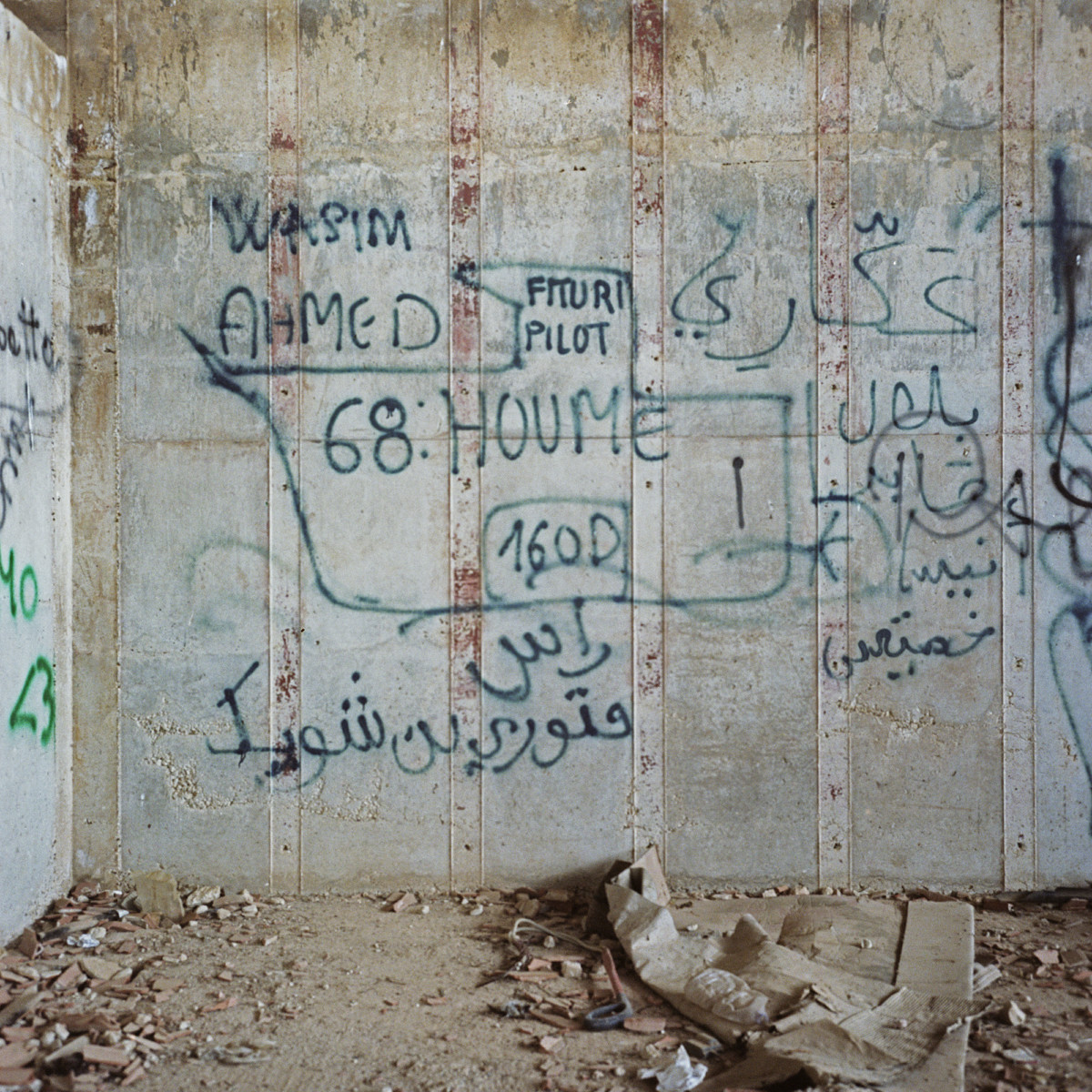

Once in Libya, Omar was arrested without charge. He shared a cramped jail cell for six months with one hundred people. There was no room for anyone to lie down and people slept back to back. At most, they would be allowed out of their cells for twenty minutes a day to walk in a small courtyard.

In jail Omar was beaten and had his ankle broken, and he received no medical attention for his injury. He relied on care from cellmates who helped to set the bone in the best way they could.

After six months in the cell, he was summoned by a guard who told him he would be released if his family sent money. He was able to get money sent to the guard and that night was released and told to run for his life. His freedom cost him two hundred dinars (around €130). Omar ran for four hours through Tripoli on his broken ankle, eventually finding an old freezer in an abandoned building, which he upturned and slept inside until morning. Once he was able to contact his broker, he was collected and taken to Algeria to board a boat destined for Italy. Omar decided to leave CARA di Mineo and is currently residing in Germany.

Musa was transferred to a reception centre in Pescara, Italy, with one day’s notice and now makes money by helping cars park by the city’s central train station.

Musa, Pescara, Italy, November 2015.

Mineo, Sicily, Italy, June 2015.

Medani, Catania, Sicily, Italy, June 2015.

Medani, thirty-three years old, is an Eritrean refugee. He traveled north through Italy to Ventimiglia and into France. I first met Medani at a car park camp in Catania and then found him again by chance in the Eritrean Christian Church in “the Jungle” camp in Calais.

Catania, Sicily, Italy, June 2015.

Madia, Catania, Sicily, Italy, November 2015.

Madia, twenty-eight years old, left Senegal crossing the Sahara in a highly dangerous convoy. Madia witnessed his best friend, Sana, being shot in the head by people traffickers. On arrival in Italy, he was wrongfully convicted of being the captain of a migrant boat and spent four months in prison. He now lives in France.

Aly Gadiaga, Catania, Sicily, Italy, June 2015.

Aly, twenty-six, left Senegal and spent three years traveling to Libya, washing dishes in Mali and Burkina Faso in order to earn money to board one of the dangerous convoys and cross the Sahara. Aly speaks Wolof (a language of Senegal), French, Italian, and English fluently. He has lived in Catania for two years and has not yet received a work permit. Everyone in the market knows him as “Gucci,” a slang term for “good” or “all right,” because of his remarkably positive attitude. He has not seen his family for six years.

Aly Gadiaga, Catania, Sicily, Italy, November 2015.

Aly Gadiaga, Catania, Sicily, Italy, November 2015.

Images: Daniel Castro Garcia, John Radcliffe Studio.

Credits: Photography by Daniel Castro Garcia, graphic design by Thomas Saxby, produced by Jade Morris.