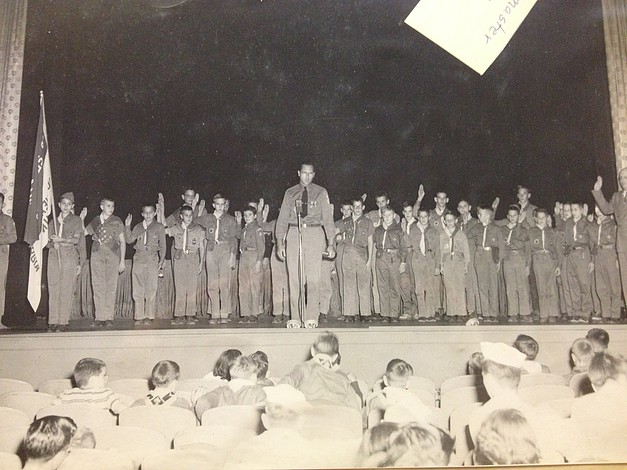

The Boy Scouts of America is an organization built around ideals: ideal morals, ideal aptitudes, ideal men. These ideals were shared by my grandfather, my uncle and my father when they were scouts. When I first put on the uniform as a ten-year-old, I signed up for the same outdoorsy, charitable manhood that they valued so much. It was a cool masculine lineage, beautiful in its simplicity: adult leaders and Scoutmasters told me that physical, mental, and spiritual self-improvement would make me an honorable man. I was unaware of how many leaders were also deeply invested in my sexual attraction to women.

I had the time of my life growing up in Scouts, but it took me until adulthood to realize how many conditions were placed on my membership. If at any point during the 2000s I had expressed anything other than strict heterosexuality— if I’d so much as mentioned a boyhood crush named Jack instead of Jill— the BSA would have required I exit the program due to its “morally straight” requirement, no pun intended. Adult leaders faced the same restrictions, perhaps even more rigorously. A 2000 Supreme Court ruling supported the BSA’s right to establish its own membership rules, even if they discriminated against LGBT fathers and mothers wanting to spend time with their sons. Not surprisingly, many people were unhappy with the ruling. So in 2013 the Boy Scouts agreed to take a vote among its adult leaders over whether or not to admit openly gay youth, signalling to some that they were on the verge of equality and to others that they were on the verge of apocalypse.

That division was felt in my hometown of Athens, Georgia, a place where “gay rights” and “gay agenda” might be used interchangeably depending on proximity to the local university. Many of the troops’ head volunteers, or “Scoutmasters,” indicated support of inclusion. “Why not?” was a common sentiment among these current leaders, though a few may have had discussions regarding equality, inclusivity, and the benefits they confer. But Athens’ legacy Scoutmasters, the men who had run troops for thirty years or more, could be far more passionate in their opposition.

If anyone was the shining image of “traditional values,” it was Boland. He was a local business-owner, a deacon, a decorated veteran and Scoutmaster who would put his name on the line to defend Constitutionalism, Creationism, and the exclusive right of heterosexuals to go camping.

“I do not want to see that gay Scouts are having homosexual relations with other Scouts on trips,” Dr. Rudy Kagerer, former Scoutmaster of Troop 22, told Nick Coltrain of the Athens Banner-Herald in 2013. As a retired Scoutmaster Kagerer had lost some of his influence; he no longer had the ability to withdraw his troop from the BSA, as some troops in the country had chosen to do. But still, Kagerer had personally mentored nearly a thousand local men when they were boys. His voice mattered, though perhaps not quite as much as that of Colonel Ernest Boland.

If anyone was the shining image of “traditional values,” it was Boland. Here was a local business-owner, a deacon, a decorated veteran and Scoutmaster who would put his name on the line to defend Constitutionalism, Creationism, and the exclusive right of heterosexuals to go camping. On his Facebook page (and yes, this 88 year-old man had an active Facebook page) there is a petition against gay people in Scouts, specifically calling for the immediate resignation of an Executive Board member for attempting to “bully the BSA into gay assimilation.”

According to Boland’s memorial website, this post was “the last thing [Ernest Pope Boland] did.” Boland died February 7, 2013, the day he shared the petition.

Boland’s death wasn’t sudden or unexpected; he was 88, after all. So what were Ernest and his family members thinking when they decided to make one last social media post? What kind of fear had to possess him to think that the policies of a youth organization were such a danger to the children involved?

What’s most troubling is that Ernest Boland used his position as Scoutmaster to allegedly rape a dozen or more boys.

“Allegedly” raped is admittedly a pretty bold accusation, considering Colonel Boland was never convicted of anything. He wasn’t even brought to trial, and the only charges brought against him were made decades after Georgia’s statute of limitations rendered them defunct. And prior to those charges, Boland’s crimes were Athens’ best-kept secret: he kept on winning his Rotary awards and serving as an honorary probation officer for the juvenile system where, you guessed it, he allegedly raped more kids.

But a publically available record of his actions does exist. In 2012 the Oregon Supreme Court forced the BSA to release thousands of private files. These were referred to as “the Confidential Files” or “the Ineligible Volunteer Files” or, in popular terms, “the Perversion Files.” In this collection there is a file dedicated to Ernest Boland and his quiet expulsion from Scouting, dated 1977. It also contains evidence of how the Boy Scouts failed to investigate accusations of child rape for years and then helped him cover up his crimes.

Most people will tell you these issues are resolved. Openly gay youth were admitted thanks to the 2013 vote (61 percent in favor of inclusion, 38 percent against), 2015 saw another vote and the immediate lifting of the ban on openly gay adults; Ernest Boland is dead, so he and his crimes are done; and the Boy Scouts now require annual training in youth protection for all volunteers, plus mandatory training for Scouts and their parents. Why unearth so much history?

A year after the July 2015 vote, gay inclusion is not at all guaranteed in the Boy Scouts of America. Any troop that is chartered by a religious organization, which accounts for seventy percent of the one hundred thousand troops, is allowed to make their own independent decisions regarding adult membership rules. Kids can’t be banned, technically, but they can be blocked from involvement in the troop as soon as they turn eighteen. Troop rules can still support explicitly anti-LGBT rules, so kids grow up knowing they’ll be unwelcome within a few years. Even when churches don’t impose doctrine as law, we still have to consider the influence of the volunteer leaders who run the troops.

Some of these leaders are undeniably bigoted, and I’m not here to defend them. But many well-meaning citizens suffer under a prevalent misunderstanding, one that may harm themselves as well as gay people. Many people still believe that pedophilia, especially towards boys, is an unhealthy aspect of homosexuality. Even though the Boy Scouts of America takes “strong exception to this assertion,” many well-meaning volunteers and parents are convinced that gay exclusion is the best way to protect their children.

That’s not the opinion of Dr. Victor Vieth, Founder and Senior Director of the Gundersen National Child Protection Center, the group that recently re-wrote the Boy Scouts’ policies on Youth Protection. He believes that increasing acceptance of gay youth can increase overall safety, but only if it’s part of a push for greater education. We have to be willing to learn about the threats, the causes, and the victims of child abuse if we want to turn away the abusers.

Because the Boy Scouts is so highly segmented, any generalization is going to cause problems. There are troops that chose to accept LGBT people years before it was required, and entire Scouting Councils rebelled against the former ban. So in a way the BSA has always been inclusive, even if the organization didn’t necessarily realize it. But national policies enforced backwards thinking, and areas that practiced exclusive policies suffered for it. The BSA’s secrecy and homophobia benefitted an unknown number of abusers— at least two in Athens and more than 5000 around the country— and it was decades before Alan McArthur, a gay man and victim of child abuse, was able to out Boland.

We need to see how inclusion, not obsessive interest in sexuality, can make the Boy Scouts a safer place.

Picked Last

Joining the Boy Scouts is a rite of passage for many young boys, like a club made specifically for big kids. In 1976 Alan McArthur was twelve and finally old enough to join, and his parents were proud of their little man. Mr. McArthur looked forward to camping trips and uniforms, and Mrs. McArthur wanted a few quiet hours around the house. They also saw it as a chance for Alan to finally make some friends, so they turned to Ernest Boland and Troop 3 to help him find his home-away-from-home.

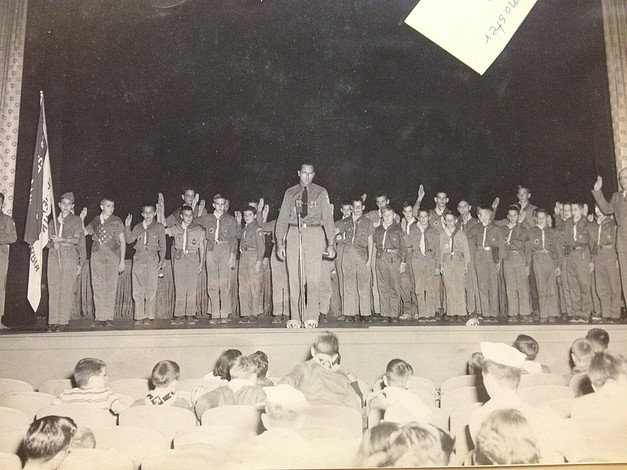

“It wasn’t like it is today, when kids are coming out and they’re embraced, and things are good.” Alan McArthur, now 52, told me. “This was back in the 70s, where even a hint of [being gay] and you were bullied or made fun of or just picked on or beat.” He fidgeted with his gum wrapper as he talked, twisting and shaping it over and over. “[Boland] didn’t go after me because he thought I was gay; that wasn’t the way he got to me. He got to me because he thought I was an easy target.”

I met Alan at the Athens county library, a newly renovated brick-and-glass building with families streaming in and out of it. Nowadays Alan seems to fit right in: he’s a lean man who wears dark-wash jeans and V-neck sweaters, much more the resident of this college-town Athens than the rural Athens of the 1970s he grew up in. We passed through the library’s springtime festival, which featured a bluegrass band celebrating the building’s new facade with some down-home tunes. Most people stopped and smiled, but Alan walked right past. It’s not that he was impatient to get started; I think he was impatient to get it over with.

“I did not know a soul [in my new troop]. I probably knew a few from school, but you have got to understand that school was not a great place for me. It all started when I was twelve or thirteen. And I was very stereotypical: I was non-jock. I was not a smart kid. I was one of the [kids] that was made fun of and bullied. I had that going on. So even though I may have known some of the guys in this troop, I didn’t have friends, I didn’t have anyone I could buddy up with. I was pretty much on my own.

“And my first experience with [Ernest Boland]— the way he greeted boys when they came to scouts— was he hugged them. They called him by his first name, which I thought was just the oddest thing in the world. And he was always hugging and loving on them. It made me really uncomfortable the first time he hugged me. I was like, ‘I don’t get this.’”

Looking back, Alan is able to see Boland’s actions for what they were. The man had a strategy in how he groomed Scouts, in how he made physical contact commonplace, and Alan has spent decades trying to understand how it all happened. “If you read the research [about] pedophiles, they seek the ones who are loners, or come from troubled backgrounds, or whatever,” Alan said. “They have a pattern that they go after, and I fit that pattern for him.”

Being gay in 1970s Georgia constituted a “troubled background.” Homophobia was the norm, and homophobia leaves LGBT kids vulnerable.

Dr. Vieth has seen the consequences of ostracizing gay youth.“There is research that LGBT children are harassed or otherwise victimized at higher levels,” he told me. “Involving these youth in organizations, and treating them with compassion and respect may open doors to preventing abuse and, where it cannot be prevented, to earlier disclosure and intervention.”

“He turned the conversation to, ‘Which one of you will be sleeping in my tent?’ And [with that came], how to describe it, this unsaid knowing. A kind of teasing between the boys. ‘I don’t want it to be me, it’s going to be you,’ whatever. It was like it was a given or a known, that this practice went on in this troop.”

It’s a pretty simple suggestion: if a boy doesn’t worry about being called gay (whether or not he is gay), then that’s one less fear to inhibit reporting. That also means LGBT kids are less likely to be isolated from their peers and more likely to make friends. If a boy feels safe and welcomed at Scouting, that means he and his friends can look forward to years of fun and growth together. Greater integration means kids are less vulnerable: boys who don’t fear reporting can help catch a pedophile early on.

But that wasn’t the case for Alan. He was gay— had same-sex attraction since 5th grade, before he even knew what that meant— and nobody in Scouting, school, or his Baptist church would accept him for that. And so Boland went for Alan, not because he was gay, but because he was vulnerable and isolated.

“I remember this one time we were going on a camping trip . . . we were in a van and [Boland] was driving, there must have been six or seven [Scouts] in there, and as we were approaching the camp he turned the conversation to, ‘Which one of you will be sleeping in my tent?’ And [with that came], how to describe it, this unsaid knowing. A kind of teasing between the boys. ‘I don’t want it to be me, it’s going to be you,’ whatever. It was like it was a given or a known, that this practice went on in this troop.

“And of course it was me. It was the first time that we wound up together on a camping trip. It felt like the other ones knew what was happening in that tent and it just happened that I was the choice that weekend. Maybe others had a similar experience with him . . . I knew of one other . . . that had been abused by him. My guess is there would have been many. It was a weird moment. I look back on all this stuff.” Alan shrugged, grimaced, and turned the conversation elsewhere.

The uncertainty Alan faces is not at all unusual; when I spoke to Dr. Vieth, he said that’s what he’s come to expect. “In all cases of sex abuse there’s an element of secrecy,” he said. “The perpetrator maybe portrays the idea that what they’re doing is a secret, which they do, in part, to justify their behaviors. Perhaps a dad picks up the child [from an event], it’s late at night, he tells them to be quiet or Mom will wake up. Or another perpetrator will threaten the child, tell them they’ll get spanked, they’ll get in trouble, that the church will condemn them.”

No matter the tactic, the abuser focuses on making sure no one finds out. “While an offender will pursue anyone they think is attractive, [the body of research suggests] in particular they will seek someone who is vulnerable. They might say, ‘Oh gosh, that boy’s parents are going through a divorce, he’s going through so much that I could take advantage of him emotionally.’ Or, ‘Gosh, this kid has drug and alcohol issues, I’ll help them and seem like a great Christian by helping them out. And if I get caught I’ll have this built-in defense’ . . . There is definitely an incentive to seek out children who are exposed and vulnerable.”

That’s how it went for Alan: he didn’t fit in with the other guys, so Boland claimed him. It was like a game of kickball, except whoever gets picked last has to sleep with the Scoutmaster. Alan doesn’t think any adults knew, and we definitely can’t prove that the kids knew. But the other Scouts kept picking Alan last— for bunkmates and for the buddy system and for being pals— and so, because he was a little less popular with his peers, he was one of Boland’s favorites by 1977.

Beyond Scouting

That year was a turning point for Boland. In May 1977 he issued a letter to his Troop Committee, resigning from the Scouts because he said he had “completely abandoned [his pest control] business during the past year, and the profits show it.” It was a surprise for many, and the end of Boland’s Scouting career. But business was demanding, and Boland decided he’d do well with Alan as an intern at the office.

“He lost his pool [of boys]. He was no longer in Scouting . . . He hired me, part of that early release, work-study programs in [our] schools. That’s how he kept me around. I’d go to his office a couple times a week,” Alan said. “He’d pick me up from school.”

This routine came to define Alan’s life. His last class of the day overlooked the pick-up line, and right at the base of the school’s marble steps he’d see Boland parked in his long, bronze Lincoln. And when the bell rang, Alan would grab his bag, head down those stairs, climb into the car, and see what Boland had planned for the day.

Though he was a teen by then, Alan was in no better position to out the man that abused him. Boland still had all the power, and even as an adolescent Alan was very much a vulnerable kid.

‘Vulnerable’ is a relative term, but as a trait it is consistently attractive to pedophiles. And contrary to popular expectations, boys are easier to coerce into silence, something pedophiles recognize as a glaring vulnerability. Dr. Vieth says that boys are less likely to report due to four societal pressures:

Boys learn these fears during childhood by observing what people value in men. They see respect conferred on one type of man and disdain on another, and they take note. When our movies and our parents and our Scoutmasters insist that manhood means being strong, being respected, and being a sexually-active heterosexual adult, boys learn to fear deviation from these norms.

Adults actively contribute to these pressures when they equate gay men with pedophiles. Rest easy: the American Psychiatric Association distinguishes between sexual orientations like homosexuality and fetishes like pedophilia. In fact, experts have found that most pedophiles identify as heterosexual, as Boland did, and these pedophiles frequently maintain adult heterosexual relationships. But society’s fear of imagined gay pedophiles contributes to homophobia.

Whether he knew it consciously or not, Boland relied on the pressures being stacked against Alan. Sometimes they’d go straight across the highway and to the office, where Boland could decide if they were safe from prying eyes. Sometimes Alan would get in the car and they would drive around, and Boland would tell Alan how special he was, a confidant, right before initiating oral sex. One time Alan got to the car and found a stranger in the passenger seat.

“It would take every ounce of courage I could muster, for weeks and weeks and weeks, to come up and say, ‘I don’t want to do this anymore.’ The first time I said it, I thought, ‘Wow, that was easy.’ And he went away for a little bit! Then he came back, and it started all over again. And then again he would say, ‘Anytime you want to stop this, it’s up to you.’”

“I think it was a college guy that he wanted me to meet. The guy was really uncomfortable, it was clear he just wanted to be let out, and Boland was like ‘I really wanted you guys to meet, to get to know one another. I just thought you should meet.’” Alan said he did not talk to him, and before long Boland let the young man leave. “And that was it, I never saw him again.”

Abusers often commit their crimes in cars, and Boland took advantage of the relative privacy. There are lots of shady, quiet spots in Athens, the kind of places you’d expect teens to make out on the way home from the movies. But side roads and parking lots were too risky for 53-year-old Boland in his big Lincoln, so he primed Alan to visit somewhere new.

“One day we were driving around and he mentioned it, and he said, ‘I have this artist studio.’ He was like, ‘This is the place I do my art, and one day, if you’re good, I’ll take you there. I take all the special boys, the good boys.’”

“I wanted to see it. I was curious what this place was. Again, this goes back to this place in my life where I was at school where I wasn’t special and this man was making me feel special . . . he played to that narrative of what I wanted to be. So we drove up to this place I guess he rented by the month, this old hotel in Athens that was typical: you walk in, it had the typical double bed, the typical piece of furniture with the TV, and the Gideon Bible, and the bathroom, in the old days all the things you’d see. And I walked in the door and I was like, ‘I’ve fucking been had.’ To the right of the door there was this easel with a little picture-painting propped up on it, and that was it. There were no art supplies, no canvases anywhere, no artwork and no project. [It was] this show. I was like, ‘I’ve fucking been had.’”

Once Boland had convinced Alan to go to the apartment, it was extremely easy for him to pressure Alan into returning. If he had gone that one time, why shouldn’t he go again? Boland could simply make a detour on their way to work, have sex at the apartment, and be in his office within the hour, the whole time assuring Alan that it could stop at any time, he just had to say so. Alan did say so, several times, though it was never easy.

“It would take every ounce of courage I could muster, for weeks and weeks and weeks, to come up and say, ‘I don’t want to do this anymore.’ The first time I said it, I thought, ‘Wow, that was easy.’ And he went away for a little bit! Then he came back, and it started all over again. And then again he would say, ‘Anytime you want to stop this, it’s up to you.’ So again for weeks I’d work up the courage to say something, and it ended.

And the third time he came around, he said, ‘I know how you can make some extra cash.’ And so he used to pay me.”

It comes as no surprise that this kind of manipulation can happen, and Alan could not have prevented what happened to him. Child rape is called such because it can’t be consented to, because children are not psychologically and emotionally equipped to understand what is going on. Alan didn’t even know he had been abused until he was 25, when a therapist pointed it out to him; he thought he had just had an early, upsetting sexual relationship.

And in any case, Alan did fight it; he fought it for quite a while. In the midst of this frightening mess of coercive, secret molestation, Alan kept trying to evade Boland.

“A lot of times I’d try and get away, avoid him, get on the bus and go home. At some point I just kind of gave in. If I went with it it’d be over soon. But one time . . . I saw his car out front, I went down, started to get in the car. And he said ‘No no no. I’m not here for you.’

And I was like, ‘Who are you here for?’ and I didn’t see anyone else in the car . . . At that point I was like, ‘There’s somebody else, it’s not just me.’ But I didn’t see who got in the car. I went and got on the bus. And I was both relieved but also kind of jealous.”

Alan kept working for Ernest Boland until 1979, the year that Betty Boland, Ernest’s wife, decided to get involved in the business. The husband and wife fought all the time, Alan recalled, still picking at his gum wrapper but smiling at the memory. The Bolands cursed and shouted at one another, though Alan never knew why, and he found himself caught between Betty’s nastiness and Ernest’s abuse. Finally, it all came to an abrupt end.

“The last time I saw him, she called me up to her office . . . because she wanted to talk to me. So I walked up there. As I was approaching her office he called her. ‘Let me talk to him.’

So I went to his office and he [said], ‘You can’t be around here anymore. She doesn’t want you around anymore.’ So he fired me. I was a mess. I cried so hard. And with my mother I think it clued her in that there was something. [Boland] called the house and wanted to talk to me and she was like, ‘Don’t you ever call this house again. Leave him alone.’ So [Betty] had to know. There was no way she didn’t know.”

And so Alan got to graduate high school, then college, without Boland assaulting him again. Alan moved out of his parents’ house and went to the University of Georgia. He graduated again, got heavily into drugs and partying, then moved out to Tucson on a whim and stayed for thirteen years. Arizona was just the change Alan needed, and the friends he found there helped him begin healing. It wasn’t an easy recovery, and it certainly wasn’t straightforward: there were relationships, break-ups, a return to Athens, long periods of depression. A friend of his, another victim of Boland’s, drank himself to death– first with alcohol, then household cleaners. Alan grieved with the family.

Then, in 2012, Alan McArthur reached his own dark place. “I found myself holding a gun in my hands,” Alan told me. Here he looked me in the eyes. “I was done. I was tired of winding up back here over and over again. I put the gun away and I found a therapist, I went to see her. I told her about what all was going on. And she said, ‘You need to file a police report.’”

The Great Cover-Up

The idea was simple: establish a record against Ernest Boland. Georgia’s statute of limitations ensured that he could not be convicted or brought to trial, but there needed to be a paper trail, just in case Boland might still be an active abuser, even at 88. So Alan went into a police station, filed a report, and made the accusations public record.

These are not the first accusations recorded, though, not by a long shot. It turns out the first accusations of Boland’s child abuse are forty years old, dating back to 1972, when he was a Scoutmaster at his first troop, Troop 22 of First Baptist Church. And we wouldn’t know that, of course, if it wasn’t for the court-ordered release of the Ineligible Volunteer Files.

Boland’s Ineligible Volunteer (IV) File was filled out mostly by Ron Hegwood, who learned of these accusations when he became the Scout Executive for the Northeast Georgia Council. It seemed pretty cut-and-dry to him: a son revealed in therapy that he’d been forced into oral sex with Mr. Boland, so his father reported the news to the Scouts. Mr. Hegwood met with the father, jotted down some notes, grabbed his forms, and set out for Boland’s newest troop, Troop 2, when he got news that halted the entire reporting process.

Boland had already quit the troop. No particular reason given, but the troop committee had been investigating him. There were a few more rumors of abuse— nothing they could substantiate, but enough to cause concern. It was probably a disappointment for everyone; if they had acted a little more quickly, Hegwood and the committee could have shown Boland the door. Instead, it seemed he had beaten them to the punch.

Resigned, Hegwood dropped the issue. That was perhaps the first time the Boy Scouts of America directly enabled Boland, because he was certainly not done with boys. He was still a Sunday School teacher and a probation officer; then again, Hegwood reasoned, he wasn’t a Scoutmaster. He might still be a problem, but he clearly wasn’t their problem.

Except Boland kept calling Hegwood and bumping into him. He had this great idea: a new troop at a new Baptist Church. He had too much of a passion for boys, it seemed, and he kept on pestering Hegwood whenever he could. In his notes, Hegwood claims that he never gave Boland a straight answer, responding to his enthusiasm with generalities and sometimes complete evasions. We don’t know the specifics of Hegwood’s dodges, but he was reasonably successful: he apparently kept Boland from creating a new troop for three years.

But Boland was a determined man. Absolute confidence had gotten him this far, so in 1975 he confronted Scout Executive Hegwood directly. “Is my name on the Confidential List of B.S.A. and can you prevent me from becoming a Scoutmaster?” Boland says in Hegwood’s files. Hegwood said no, and so Boland started Troop 3.

Is that how it happened, though? Did Hegwood let Boland continue working with boys due to a technicality? The IV File may have been the BSA’s official defense against abusers, but there was no reason the problem couldn’t be handled in-community. A conversation with a church committee in 1975 might have kept Alan McArthur from meeting Boland in 1976. So it’s perhaps a little odd that Hegwood acted like his hands were tied.

Really only two of them read the files. Joseph Anglim, the director of administration, was so clueless as to the files’ content that he was unable to guess the number of abuse cases a year.

And Hegwood’s account is suspicious, mostly because of the words he attributes to Ernest Boland. In that one quote Boland shows a surprising knowledge of something that was supposed to be capital-C ‘Confidential.’ These files were completely unknown to the outside world, at least until a 1991 Washington Times series covered the history of abuse in the Boy Scouts. Prior to that the BSA didn’t even tell their Scoutmasters about the files, much less that the files contained details of hundreds of child abusers. Any local files on the abusers were sent to the national office, and in the instances where police got wind of the accusations they were typically convinced not to mention the Boy Scouts in their reports at all.

There were, in fact, only three people in all of the Boy Scouts that worked directly with the files as of 1975: the director of registration, the director of administration, and the general counsel. These three men would schedule a get-together to rubber-stamp the files, but really only two of them read the files. Joseph Anglim, the director of administration, was so clueless as to the files’ content that he was unable to guess the number of abuse cases a year. “One or two a year,” he told author Patrick Boyle in 1990 for his book, Scout’s Honor. “One case is too many. One case is a disaster.” When pressed as to how he could not know that he stamped two- to three-dozen files for child molesters a year for more than ten years, Anglim told a court in 1988 that, “I have never read a Confidential File.”

The national leaders responsible for the Confidential Files didn’t have to know what the files were for, and professional Scout leaders at the regional level knew the Confidential Files existed but weren’t allowed to keep their own files. Volunteer leaders were supposed to be perfectly ignorant: every Scoutmaster or adult volunteer I’ve spoken to from the time hadn’t heard of the files until the 1990s, and some only learned of them when I asked. It is safe to say that the vast majority of Scouting adults had no idea what the Confidential files were.

Except for Ernest Boland, who in 1975 had such a mastery of its loopholes that Hegwood couldn’t help but let him start a troop— and in such a way that Hegwood faced no responsibility.

I have my suspicions about the veracity of Hegwood’s records: at the time they were written, after all, few people reviewed the files, and there was practically no chance of the Boy Scouts releasing them. With very little oversight, people like Hegwood didn’t have to worry about someone double-checking their work. But it’s difficult to prove my suspicions; when I called the Hegwood residence, I was told I should, ‘Let it die’ and that it was all ‘a hundred years old, anyways.’ Even if he had spoken to me, Hegwood could stick to his story. That’s the power of the Confidential Files: they protect not just the abuser, but they also help shield those who should have stopped him.

The rest of the story unfolds like a tragedy. In 1975 Ernest Boland started Troop 3, and by the time Alan McArthur joined a year later there were already victims. Accusations returned, this time with almost a dozen possible victims, but again it was all kept quiet and away from authorities. Hegwood couldn’t get anyone to provide hard evidence, so he went instead to Boland’s pastor.

Reverend James Griffith ended up providing the final nail for Boland’s Scouting career. The Reverend was a prominent Baptist in the area and a former reporter, so perhaps it was his nose for news that led him to Boland’s secret apartment. While asking around he also learned that Boland had bought airline tickets for two Scouts to stay in a Maryland motel with him for a week in 1977. Naturally incensed, the Reverend took things into his own hands: he called up two deacons, asked them to chat with Boland, and took no further action until Hegwood arranged their meeting.

At this point the two community leaders apparently had sufficient evidence to bring Ernest Boland to trial, but of course that’s not how this story goes. Hegwood and Boland met in private; no accusations were made, but the next day Boland delivered his letter of resignation. He cited business concerns, and no one contradicted him.

The Stakes

When I began research on this article I had a hard time getting professional Scout leaders from the Georgia Councils to talk to me. Not because I aim to tear down the organization— all things considered, my Scouting experience has been as-good-as-advertised— but because these leaders had just become swamped with litigation. While I was asking about Boland, they were getting sued over two other abusers and former Scoutmasters: Fleming Weaver and Richard Merrey.

These two men illustrate the threats still looming over Scouting today. Weaver represents the historic threat to Scouts and Scouting: like Boland, he was caught decades ago and even confessed to Scout leaders that he had abused Scouts. Also like Boland, he was never charged with any crime, only encouraged to seek professional help. Unlike Boland, however, he is being brought to court, as is the BSA for its failure to report Weaver. The plaintiff in the case claims that the 1985 rape he endured at Weaver’s hands could have been prevented if the Boy Scouts and the sponsoring church had “done their legal and moral duty to protect children by reporting Weaver’s admitted abuse of at least 5 children,” emphasis on “admitted.” Local Scout leaders in Gainesville, Georgia knew of his crimes because he confessed them in private, but Fleming Weaver did not get his Ineligible Volunteer File until 1995, and it is still not available to the public. He is an example of how Scouting’s old, meager protections failed the kids.

But where Fleming Weaver threatened boys who have long since grown up, Richard Merrey’s victims are just reaching adulthood. In 2011 Merrey was found guilty of sexually abusing children in Chatham, Georgia, and was sentenced to 52 years in prison. Now one of his victims and former Scouts, who has just turned 18, is suing the Boy Scouts. His case alleges that the BSA let Merrey continue as an adult leader despite his confession to exchanging sexual texts with a 13 year-old boy in Ohio.

Abusers continue to be drawn to Scouting, partially because of the difficulty in upholding the BSA’s rules on youth protection. Richard Merrey was able to abuse kids largely because no one at his troop enforced the rules, and no one at the Council checked to see if they had. Background checks, two-deep adult leadership, and training are only effective as far as they are enforced, and anyone that makes exceptions endangers the kids.

If a Scoutmaster has to disabuse boys of notions like “sunscreen is for girls” or “raccoons are friendly tree-cats,” shouldn’t they also disabuse them of the notion that “gay is bad”?

For all the good efforts and the improvements of the national organization, the BSA still relies on its local leaders to protect the kids. That’s a lot of responsibility for volunteers, and clearly it doesn’t always work out: the 2016 case against Merrey claims his Scoutmaster didn’t run a background check, Weaver’s troop committee let him go on Scout camping trips, and Boland got away because no one wanted to ruffle any feathers.

The high stakes of child safety are most conspicuous when parents are searching for troops to join. It has always been the parents’ responsibility to discern between one troop or another based on things like the cost of camping trips, the convenience of troop location, the safety of their boys. If a parent is already well-informed about the threat of abuse, then they can ask the right questions. If not, then the boys’ safety is again the troop’s responsibility.

Troop leaders are obligated to protect the Scouts, both from physical and non-physical harm. Scoutmasters watch for fire hazards, rough play, and poison ivy, but also isolation, anxiety, and depression. They are called to see the potential harm in any given situation not because they need the stress, but because they’re supposed to spare the kids from that stress. So if a Scoutmaster has to disabuse boys of notions like “sunscreen is for girls” or “raccoons are friendly tree-cats,” shouldn’t they also disabuse them of the notion that “gay is bad”?

Fighting homophobia (a word that literally means “fear of homosexuality”) is admittedly just one small way to prevent abuse. Boys who don’t fear homosexuality are better prepared to report abusers, but so are boys who don’t fear weakness or societal backlash: why should I or anyone focus on accepting gay people?

If some troop out there figures out how to dismantle toxic masculinity, let the rest of us know. But being gay is the major trait that troops bar against, that leads to whole new organizations forming with “Christ-centered” bans. Moms and Dads want to know that Junior won’t be hanging with gay guys, and if Junior ends up being gay? That’s tough luck, I guess. It sounds silly, but some parents are actively seeking troops that will expel their gay sons.

All this misplaced energy is tragic in part because it’s an impediment to the truly great things that the Boy Scouts can do. As a kid I was in a troop that consisted of mostly blue-collar dads and their sons, usually boys who were either a little hyperactive or a little surly or a little lazy, and somehow we still turned out for Saturday community service when our Scoutmasters asked. Once every other month or so a bunch of teens got together to build park benches and church pavilions, to clean trailers and clear cross country tracks; when I earned my Eagle Scout rank, I had to plan and build a 112-foot walkway for an elementary school. I’m proud of that work, just like I’m proud of the seventy-mile canoe trips and the towers we lashed together with rope; I’m proud of the first time I pitched my own tent and of the first time I taught someone else to do the same. Scouting is amazing when you let anyone and everyone have a shot at adventure.

But kids can sense when they’re not welcome. We need a cultural shift to support gay members— and bisexual members and lesbians and transgender people, etc.— because the Boy Scouts of America has been so much more effective, and deliberate, and vocal about keeping out LGBT people than they have child rapists. We need to face the reality that, yes, the BSA voted to no longer ban LGBT adults unless some pastor disagrees. We need to see that now, just like with Alan McArthur in the seventies, leaving gay people isolated and vulnerable is considered the cost of doing business.

And at the risk of sounding cloying, I’ll ask you: won’t you think of the kids? Some of them will be gay, whether or not they know it when they join, so maintaining a ban means that adult leaders have to be ready to shun the Scouts when they turn eighteen. How do you invest in a child’s future while maintaining a hostile environment? And how is a kid supposed to feel welcomed if their adult counterparts are scorned?

Unofficial Scout records suggest that, since the change of rules in 2015, the organization has grown for the first time in decades. We are at a point where families have renewed their belief in Scouting, where parents see troops and Scoutmasters as trustworthy stewards of their children’s safety. This is not the time for the BSA to rest on its laurels. It is a time for concerted self-improvement, for acknowledging past mistakes and fighting to prevent them from reoccurring.

Troops in Athens have already decided these changes are worthwhile. Troop 22 of First Baptist Church, for years the troop and church Ernest Boland called his own, is now accepting LGBT members. In fact, First Baptist is now Alan McArthur’s church. It is where he worships and plays piano every week, and it is where Alan has found a second home.

“You can’t ask for a better church. You really can’t,” Alan told me. That’s how Alan speaks about the people who have shown him love: he knows the value of real affection and care, and he honors it tremendously. The day Alan shared his story of abuse through the local newspaper the church congregation met him at his piano. “They all came up and were hugging and loving on me, and telling me how proud they were of me,” Alan said, smiling at the memory. “They’ve been supportive of me the whole entire time.”