In Civilization and Its Discontents Freud imagines memory as Rome, a city built upon the layers and layers of past cities going all the way back to the Palatine Hill.

Palestinian-American poet Fady Joudah writes that:

“memory shrinks until it fits in a fist

memory shrinks without forgetting.”

And Oliver Sachs writes that the past is embedded, as if in amber, until music stirs it back into life again.

Other metaphors for memory: lines in a leaf, a match connecting fire to fire, writing in the sand, file cabinets, boxes, a fog lifting, a crumpled piece of paper slowly unfolding, a library, a phoenix rising from the ash, knots in a string of beads.

Memories are not contained in anything. They are not photographs that are stored the way scrapbooks are, latent until flipped open.

Really, metaphors are all we have to describe memory. After all, they can’t be located in any specific area of the brain. Not that they haven’t tried to find them. In the 1930s, neuroscientist Karl Lashley did extreme things to the brains of rats to try and get them to forget how to run a maze. He cut, he prodded, and he even used his wife’s curling iron to try and burn different are-as of the brain. But no matter how he mangled their brains, the rats still remembered.

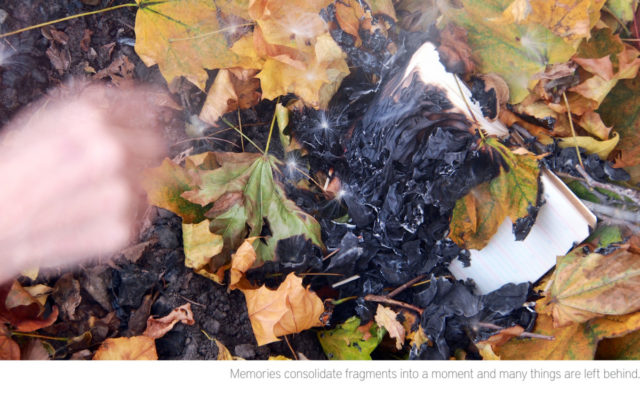

Memories are not contained in anything. They are not photographs that are stored the way scrapbooks are, latent until flipped open. Rather, they are fragments of information, and they are not only visual. They are sensory, tactile, and aural. They assemble when triggered in our entire bodymind system, the way dust gathers around the electromagnetism of sunlight. We collect fragments, and sometimes, those fragments coalesce into pictures. They call this “consolidation.”

Although there is no specific area of the brain where memories are stuck in time, most people associate memories with storage—as if we can simply open up a box and see memories, flipping like pictures in an album. Perhaps this is why we keep things. We think that objects and documents from the past are the past. And it seems so painful to let these objects and documents go, even if the past is no more contained in them than it is locked away in one segment of our brain.

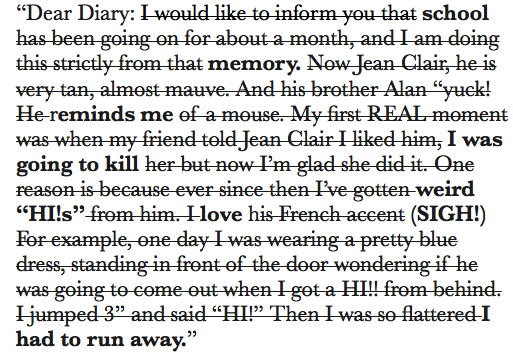

It is perhaps for this reason that diaries hold an incredible power. They hold the power to reactivate fragments of experience into pictures that had long been forgotten. They hold the power to re-trigger certain experiences that will, effectively, have the power to submerge other memories. They have the power to remind us of things that are better left forgotten.

And yet, as I grow older, I am beginning to think that associating the past with storage causes more anxiety than it does epiphany.

Like many writers, I have been keeping diaries and notebooks since I was very young and consequently, I have amassed quite a collection of boxes containing notebooks, binders, and random photographs. On top of that, since my mother passed away when I was quite young, I also have a box filled with random ephemera from her life — letters, cards, and day-planners. Every time I return to the boxes with the intention of reading through old diaries, or somehow being inspired by memories triggered by 1970s ephemera, I become anxious and consumed with feelings of dread. It’s as if the light in the room darkens and time suddenly comes to a slogging halt.

So much for Hallmark moments.

Obviously, I prefer not to trigger this kind of reaction and so those boxes sit in storage in my basement. But I am aware that they are there. And this awareness is layered with many conflicting thoughts.

I took two school notebooks that held very little emotional attachment by way of information or memories, and I tore them into shreds.

Because they cause me such anxiety, part of me wants to burn them in a bonfire ritual about letting go, shedding the skin of the past, and moving forward into the future no longer telling the same old stories. I perform burning rituals periodically, and as part of my hypnosis coaching practice I invite friends and others from the community to come and mark the solstice and equinox by burning something that symbolizes the changes people are wanting to make both personally and in the eco/social world. [here is a blog post about a recent solstice ritual]

But burning diaries or other relics from the past has never been a part of these rituals. In part this is because I don’t really believe that intentionally burning things from the past erases the past. It’s one thing to burn clutter in a symbolic “potlash” of releasing old stuff to make way for the harvest. But diaries are laden with history, and given that there are so many people without homes, caught in between political borders, and subject to systemic systems of erasure it feels incongruent and on the wrong side of privilege to just “erase the past” as if “letting go” is somehow a choice in a world where most people are forced to have to live with uncertainty, and not because they have chosen to do so.

And so there is a part of me that wants to meticulously photograph every page of every diary and archive them forever. And then I think, really? That is SO self-indulgent and time consuming, and seriously, who cares? This part of me then says, just keep them! Don’t make a decision. What else are basements for but to put all the stuff that you can’t deal with in the present moment?

With those three parts in conflict, you can imagine what actually happens: nothing.

Or, the opposite: sudden bursts of energy to transform them into art projects.

Over the years, I have tried to do several radical things with my diaries and notebooks. I took two school notebooks that held very little emotional attachment by way of information or memories, and I tore them into shreds. I then used the shreds as decoupage over a paper lantern. I like the lantern—the small bulb nicely lights through the text, making it still readable as text but not in any specific way.

I thought about transforming all of my diaries into paper lanterns, but then I realized that this would take up more room than the boxes of storage. And somehow that defeated the purpose.

I then returned to the idea of burning the diaries, but not as a ritual of release. Rather, to use the diaries as material for a book of poems—the idea was to burn each page of the diary, and as they burn, take photographs of the pages disappearing into the flames. My thought was to create an erasure poem out of whatever text surfaced, something like this:

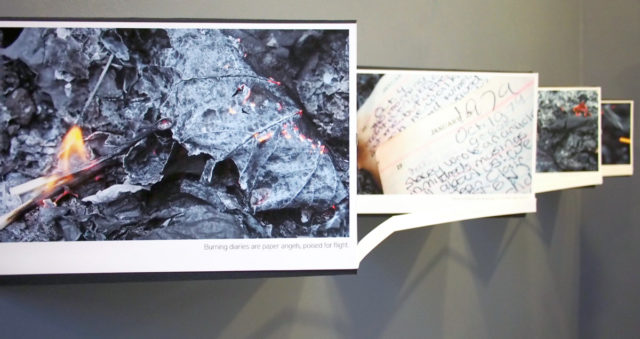

In this way, the fire would be like a writer, composing its own text as the flames destroyed the diary. And this would be a metaphor for memory. Photographer Suzanne Levine loved the idea, and so we set out to collaborate on a project.

But fire doesn’t burn through paper the way poets cross out words. Fire curls paper into itself, or it burns in strangely straight lines. Fire turned out to be a willful collaborator because it turned out that the performance of burning the diary revealed a different kind of beauty, a more universal sadness that had to do with the sheer process of watching this powerful and symbolic object transform into something else.

Paper, when caught in the moment of burning, folds into itself. When this paper is a diary, time folds into itself.

In reviewing the thousands of time-based frames that she had grabbed from her video footage, Levine found pattern, contrast, and geometry. She found color: grey and black juxtapose with orange, brown, and red. White milkweed seeds fall on white paper. Grey ash has multiple hues, and becomes almost blue.

But she also found time: Fire when caught mid-flame takes flight. Paper, when caught in the moment of burning, folds into itself. When this paper is a diary, time folds into itself. And this folding into time conjures the past and the present simultaneously.

And so whatever memories were contained in my diary: the secret desires and the dreams; the heartbreak, and the loneliness. All of that has been released from the diary’s pages. She no longer bears the weight of my lonely childhood.

Now free, the diary herself is the phoenix and the ash. She has become something else. An enigma with wings. In this way she symbolizes both the violence and the tragedy of erasure. After all, forgetting is an adaptive response. In the case of trauma, it’s a key to survival.

And fire is the medium that best conveys how “letting go” is simultaneously a decomposition and a transformation.

And of course, although my diary is mangled, I still remember…

This essay accompanies “Nothing Erased But Much Submerged,” a word & image collaboration between poet Kristin Prevallet and photographer Suzanne Levine. The show is currently on exhibit as part of the “Drawing on Language” exhibit curated by the Hastings-on-Hudson Arts Commission, on display through June 23rd at the Municipal Building Gallery in Hastings-on-Hudson, NY. In this collaborative performance, Prevallet burns one of her many diaries in a ritual of textual erasure as photographer Suzanne Levine captures images of the burning text. “Nothing Erased But Much Submerged” reveals memory as a process in which fragments of earth, emotion, and paper are consolidated into a singularly charged moment in which fire burns through the pages of a young girl’s diary.