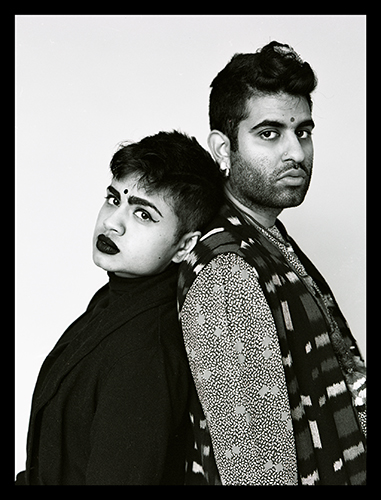

In a 1979 interview with Adrienne Rich, the writer and activist Audre Lorde argued that “the learning process is something you can incite, literally incite, like a riot.” To watch the trans South Asian performance-art duo DarkMatter perform, and to speak with Alok Vaid-Menon and Janani Balasubramanian in person, feels like both an education and an incitement—an incitement to think, question, dismantle, reassemble, perhaps even to riot.

I first saw DarkMatter perform at The Mercury Lounge, a small, punkish concert space in the Lower East Side. The show was sold out, and the audience was the most diverse—and least white—crowd I’d ever seen at the venue. It was a bare bones show—no set, no props, no costume changes, just words. The performance began with Vaid-Menon and Balasubramanian standing side-by-side, staring at the audience. Balasubramian began to chant while Vaid-Menon recited—softly, but with intensifying urgency—a poem titled “The Story They Never Told Us,” about the introduction of sodomy laws into India by the British, which introduced new and destructive taboos and phobias while erasing centuries of queer history. The evening’s performance at times resembled a political rally, a downtown drag act, an agit-prop polemic, a stand-up routine, and a traditional poetry reading. The duo performed much of the text together, talking over one another, jumping in to complete the other’s punch line: “I hear white men have huge—” “—Empires.”

Vaid-Menon and Balasubramanian are not only raging against the capitalist machine. They would also like to dismantle the patriarchy, destroy the apparatuses of white supremacy, and undo the pink-washing of an assimilationist cis-white-male gay-rights movement, among other things. But to limit a discussion of their work to its politics would not be a full or accurate representation, because Vaid-Menon and Balasubramanian consider themselves to be artists first and foremost.

Although DarkMatter have impeccable comic timing, they made it clear they were not there—and are not here—to cheer us up. In some pieces, an impassioned Vaid-Menon got hoarse from screaming about the injustices and violence suffered by trans people. Balasubramanian has a more subdued approach, but also never failed to remind us of the extreme and oppressive nature of the white colonialist-capitalist juggernaut called the Western World.

Given this characterization, it would be easy to imagine Vaid-Menon and Balasubramanian as grave personalities. Instead, at their suggestion, we met on Flatbush Avenue at a cute, tumbledown café which also doubles as a framing shop, where our discussion of the Powerpuff Girls and Paris Hilton blended easily with wide-ranging critiques of colonialism and capitalism. The mixture of levity, sophistication, and campy humor with which they approach even the most serious of topics is essential to understanding what makes the duo exceptional, not only as performers on stage, but also as trans people and activists navigating a complicated and sometimes threatening world.

—Kevin St. John for Guernica

Guernica: So much of your work satirizes the white male cis patriarchy. But here I am, a white cis man, interviewing you. I don’t know what that means, but I want to start by acknowledging that.

Alok Vaid-Menon: Hopefully, by the end of this interview, we will help you recognize that you’re not cis.

I don’t believe in men. I’ve never met a man in my life.

Guernica: Please do.

Alok Vaid-Menon: I don’t believe in men. I’ve never met a man in my life.

Guernica: Okay. Please help me understand that.

Alok Vaid-Menon: I think one of the biggest betrayals that a lot of people don’t understand is that the term “gay” was never about signifying sexuality. When the gay liberation movement started, it was actually about political confrontation of gender as a system, and some of the foundational divides in the gay movement were between gay men who wanted to assimilate into masculinity and gay men who were challenging the very idea of masculinity.

What happened in the gay movement was that trans became the space for gender non-conformity, whereas gay became nice, palatable, assimilate-able. For me, that feels like something imposed on us by heterosexual society—that you have to be men in order to validate your sexual desires, that your queerness is so ominous and threatening that it has to be in a man’s body in order to be understood.

Janani Balasubramanian: I think what Alok was saying with the idea of how we’ve never met a man in our lives, is that manhood is not just an ideal of gender; it also becomes a set of ideals around race, class, respectability, purchasing power, whatever. I’ve never met a single person in their lives who’s rich, has no feelings, goes to the gym every hour, drinks protein shakes all day. This person doesn’t exist.

Alok Vaid-Menon: They’re a fairy tale. What’s difficult is that gender has become only the domain of trans people and women. But we all have gender, and we all have a stake in ending gender.

Guernica: So gender for you is not just about presenting as male or female. It also engages your race, your class…

Janani Balasubramanian: …your aesthetics, your ideas, what you think about when you wake up in the morning, the cereal you eat, who you fucked last night, whatever.

Alok Vaid-Menon: Honestly, the issue with the way we talk about gender right now is that the term “gender identity” is completely wrong; it’s a terrible direction. Actually, gender is a relational system. My gender is produced by talking to you. The type of gender that I’m creating right now with you is very different than the type of gender I have with Janani, it’s different than the type of gender I have with my mother. It’s contingent on space. I have to make evaluations of, can I wear a dress right now, can I not, because of my proximity to violence? These are all decisions that I’m making, because gender is something that I don’t own.

Janani Balasubramanian: This is something that I think people do innately know: that who they are changes from space to space. Put more simply, that’s what it means—that you’re not the same person all the time. If you were you’d be boring. That’s not who we are.

Alok Vaid-Menon: For me, the pitfall to the trans movement is that rather than challenging that, trans people have actually been like, “Cis people suck.” That’s not a useful starting ground at all. I think it’s more interesting to say, “None of us fit in.” None of us actually fit into any of these gender taxonomies. And the people who are visibly gender non-conforming like us are experiencing the brunt of the violence, but actually, everyone experiences gender violence.

Guernica: Is the dream to live in a world where gender is totally fluid, or a world post-gender?

Janani Balasubramanian: I don’t have those kinds of dreams right now, really just nightmares.

Guernica: What’s the dystopia then?

Janani Balasubramanian: We’re living in it. This is the dystopia, and that’s what people don’t understand. It’s really bad right now.

Guernica: I’ve seen online that Janani, you describe yourself as an anti-capitalist and, Alok, you’re an anti-colonialist. Does that still apply?

Alok Vaid-Menon: I don’t think so.

Janani Balasubramanian: I think it was a useful way of introducing ourselves and getting people thinking about those things.

Alok Vaid-Menon: So much of what I understand the left is interested in doing these days is the politics of naming things—“that’s racist,” “that’s problematic,” “that’s heterosexist.” We’re so obsessed with categories and categorization in language. I think a lot of how I became politicized in the left was by learning how to identify things as fucked up, and being like, “Capitalism did this, colonialism did this.” Then, a lot of what being an artist is, is actually unlearning that leftist political education. For me, analysis of feelings—which is what I think being an artist is—is recognizing that I can hold that capitalism and colonialism are actually the same things and not the same things at the same time. Of course I’m contradictory, but I don’t need to justify that, because I’m always theorizing from the places where I’m at emotionally.

Guernica: You allow so much room for irony and paradox in your work. For example, in your piece White Fetish, instead of railing against white people, you enumerate all the ways you love white people and their problematic behavior. Did you arrive at your sense of irony over time, or did you always set out to kind of complicate the rhetoric of activism while still being active?

Janani Balasubramanian: I think that that particular performance or creative style comes from two places for us. One is this sort of queer camp tradition of being a lot of things at once, holding a lot of things at once, and then participating in irony and humor that’s not always nice, like unpleasant humor, uncomfortable humor. Then I think a lot of that inspiration, at least around irony, paradox, bad jokes, whatever, totally comes from my family, is totally their style of conversation, which I realize every time I talk to them. If anything, my family is really good at holding a lot of things at once. They don’t really know what I do, but they still love me. I think that is a type of paradox-holding that is more profound and interesting to me than anything that could be theoretically or verbally expressed.

Guernica: And for you, Alok?

Alok Vaid-Menon: I love drag queens, I really do. I think drag queens are some of the most important political figures in the world. It makes me very sad that people don’t understand the history of drag, and how the history of drag is actually a racial history. What we see as drag queens today, typically racist, trans-misogynist, white queens, who are doing blackface and doing terrible things. I don’t claim that. I’m not interested. That’s capitalism; that’s not drag.

There’s a very, very long tradition of black and brown people who were presenting drag as a way to make political commentary, and who were actually in drag as an act of doing political work. Their gender project was part of the bigger revolutionary struggle. That trans-feminine people were not just drag queens on a stage but also on the streets. There’s this weird way within western culture where trans-femininity is seen as something frivolous and excessive, but actually there have been militant trans-feminine people across the world, arguing for the self-determination of our people.

If we do not allow ourselves to be humorous and funny and catty and peculiar and awkward and crass, then we’ve lost.

For me, when I say that I love drag, I love drag because I feel like we’re in an era of both hyper-political correctness in the left and hyper-professionalism in the rest of the world. There’s no space to actually say what you feel anymore.

Janani Balasubramanian: Or to be weird.

Alok Vaid-Menon: To be strange. I’m not saying that everyone should say what they feel, because a lot of people need to shut up. What I’m saying is, if we do not allow ourselves to be humorous and funny and catty and peculiar and awkward and crass, then we’ve lost.

Janani Balasubramanian: I think one of the reasons that colonizers colonize is because of their insecurity and because of their lack of capacity to explore their own strangeness, peculiarity, all these aspects of themselves that they bury very deep, deep down, and the only way to fill that void that they create is by taking and taking and taking and climbing their way to this false top.

Alok Vaid-Menon: I’ve never met a real top in my life. But these white men are so, “Why do you care so much about identity?” And I’m like, “Baby, your entire world was built on identity.”

Janani Balasubramanian: Their identity is the most fraught one there is.

Alok Vaid-Menon: Yes. They literally invented universities so that they can have an identity. They invented the United States so they can have an identity. It’s so funny.

Janani Balasubramanian: Went real far.

Alok Vaid-Menon: I think there’s a direct correlation between the amount of gender violence I experience and how funny I am. I think that I’m funny from a place of survival, which I think also needs to be named. I’m constantly made to be the butt of jokes. Constantly. If I walk around on the street, everyone is going to be like, “That’s so funny, a man in a dress, what could be funnier than that?” I’ve had to—my entire life—learn how to be on a stage in order to get access to resources that I want. I think there’s actually something very profound about flipping the script, and not just being the butt of a joke but making fun of other people.

Janani Balasubramanian: Being, like, a white man in a suit—what could be funnier than that?

Alok Vaid-Menon: Yeah, hilarious. I think that’s the way that I survive. A lot of people are like, “How do you get through it? How do you do it? So much violence, you can’t be yourself.” I’m like, “I make a lot of jokes.”

Janani Balasubramanian: And eat a lot of noodles.

Alok Vaid-Menon: Yeah. And when I say drag, too, this is what I’m most trying to get at: that cis-gendered women can also be drag queens. Drag is about a social recognition that gender is so LOL. It’s a recognition that because gender is LOL, I’m going to have fun with it. For me it’s like, we’re all already drag queens, but some of us have already acknowledged that we’re drag queens.

Janani Balasubramanian: It’s like, gender is LOL, so we’re going to LMAO.

Guernica: You mentioned family—specifically, Janani, how your family forms a big part of how you’re able to hold contradiction, and that they love you but don’t really know what you’re about. I’ve seen both of you talk about how you are both disappointments to your family; I wonder if that is still true and what that feels like.

I think the goal is precisely to become a disappointment to our parents.

Janani Balasubramanian: I talk about this dynamic all the time. It’s very interesting to me. My parents, for the most part, don’t say to my face, “Good job,” but I’ll hear circuitous things. This relative or that relative’s wife will tell me that my parents are proud of something that I did. The unarticulated stuff is actually really interesting and powerful to me—almost moreso than the “I love you, kisses.”

Alok Vaid-Menon: I think the goal is precisely to become a disappointment to our parents. And to our families more generally. Because in the context that Janani and I are in, often the norms that our families are creating are not innocent norms. They’re norms to propagate ongoing conquest. Our families want us to be doctors not just because they’re conservative but because they want us to make money to be able to fund other peoples’ oppression. And so I think what’s very difficult is that I’m deeply committed to the project of the liberation of my family and my people, but then also believe that they have done a lot of fucked up things in the world, and I’m just not interested in participating in it.

Janani Balasubramanian: And I think there is a type of love to be had in believing in all our collective transformation. I think that is a deep type of love that often doesn’t get recognized as such. Sometimes it gets recognized as hatred.

Alok Vaid-Menon: I suppose I’m less interested in being accepted or understood by my family as I am in shifting my family’s consciousness.

Janani Balasubramanian: And allowing them to shift ours also, right? There’s this type of silencing that older generations of my family have gone through that I have not experienced in exactly the same ways. So for me, it’s hearing their stories, allowing them to experience those things. Because, really, a product of society is shutting people down and constantly telling people to shut themselves down, shut parts of themselves out. I think the horcrux from Harry Potter is actually a really good metaphor for white supremacist capitalist hetero-patriarchy. You have to break yourself into little pieces, store them in different things and call them careers, call them children, call them a mortgage, call them a dog, call them whatever. Then if those things die off you’re, like, losing yourself.

Alok Vaid-Menon: So much of what we are trying to do in our work is to flip the script about the ways we talk about white privilege, heterosexual cis privilege. Those states of being are actually the processes of becoming a zombie.

Janani Balasubramanian: The type of trade you have to make is a cultural, empathetic, emotional death. You give those things over in exchange for this thing called white privilege. And that’s the bargain. That’s what we’re contending with right now.

Alok Vaid-Menon: What people don’t understand is that liberation is going to look like a type of happiness that is neither ephemeral nor linked to capitalism. Men are totally going to love the dissection of the patriarchy. It’s like, straight people are actually going to have good sex. It’s going to be incredible. White people are going to actually learn how to dance. It’s just going to be great for everyone involved. And that’s what’s so annoying: the people who are most repressive of the type of political work that we, and the communities we are part of, are doing are the people who are the most repressed. We are trying to grapple with a type of empathy and a type of respect that understands that talking about communities that are disadvantaged by systems only gets us to a limited place. What we are saying is that the destruction and obliteration of these systems is actually going to help enfranchise everyone. And we all have a stake in it.

The success that we gain is not an endgame. Representation is never an endgame.

Guernica: What are the steps to destroying those systems? And also, what does your everyday activist life look like?

Janani Balasubramanian: I write a lot of emails, make a lot of jokes. We post a lot of things. We write a lot of stuff.

Alok Vaid-Menon: I think we all have different roles. What we’ve really tried to figure out in the past few years is, what is our unique role? How can we most leverage the power and privilege that we have in order to help out? I think it’s about recognizing that for those of us who are middle class, which we are, the work that we’re doing is largely harm-reduction.

Janani Balasubramanian: The success that we gain is not an endgame. Representation is never an endgame.

Alok Vaid-Menon: No way. A lot of rich white people are going to be like, “I love DarkMatter,” and then shit on poor trans people in the street. I can hold that, right? In politics, I understand that incorporation is the name of the game, that liberalism will take certain people and be like, “Success stories!” And then shit on everyone else.

And I know that my work, my livelihood, my images can be used against my own people. That’s the contradiction of doing this type of work. When we think about what it’s going to take to obliterate the system, the first thing is an acknowledgement that there is a system, because we’re still in a political economy where people only understand oppression to be interpersonal, which is so boring to me.

It’s very clear that when we write about, “I got called a terrorist,” or, “I got called a faggot,” people are like, “Oh my God. Yeah, that sucks.” The solution then becomes, “That’s a bad person,” not, “This is a bad world.” When I write about my empathy and my love for the people who hurt me, that’s more complicated for people because they don’t understand that the root cause is not that person at all. It’s a structure that we live in.

First, it’s about mass political education about what systematic violence is and a history of what state violence is and continues to look like.

Janani Balasubramanian: It’s not always going to be clear what the result of those things are. You can’t be fully committed to results or profit in the same way that I think capitalism drives us to be, where you can see the direct impact of everything—except in finance, where we’re not supposed to see anything. The work of social transformation is often very, very invisible work, both the means and the ends. It’s like: do things, but don’t expect anything.

Alok Vaid-Menon: When people ask me, “How do I help the transgender community?” I say, “Start carrying a purse around.” Why is that not part of our political economy? If you’re a white person, it’s going to be going home on your vacations and talking about hetero-patriarchy, talking about the enduring legacy of slavery. You’re not supposed to talk about these things, but we talk about them all the time. Be the kill-joy.

Janani Balasubramanian: Be the kill-joy. And you don’t have to be mean; you can crack jokes. I’m a really great kill-joy when I go home.

Guernica: What does it look like when you write for a performance?

Janani Balasubramanian: We have different writing processes. I have a very hyperactive subconscious, so I come up with a lot of material in my dreams, and then I just write it down and edit it. Or I come up with a lot of ideas when I’m running. It’s mostly in these meditative dreamlike states where I come up with something.

Alok Vaid-Menon: I don’t really have a writing process; I have a living process; the moments that I’m writing don’t feel separate from the moments in which I am producing other types of discourse. I’m an artist, which means that when I get dressed, when I’m speaking, when I’m talking to you, when I’m gesturing, when I’m thinking, when I’m eating, when I’m fucking—it’s all intentional, darling. It’s all just part of a bigger thing. I actually feel like my biggest art form is my social media performance. Honestly, when I think about my life’s work and what I’m doing, I’m like, look at my Instagram feed, darling. Look at it. Let’s talk about the privileging of the text over the image as a patriarchal project, because beauty is just the domain of femme. Look at this, this is me last night, getting across the political message, using internet memes, and looking good while doing it.

Under capitalism and colonialism—but they’re the same thing, remember!—femininity is also constructed as excessive. The default body is always masculine. We have to put on a dress, and then we become feminine. We have to purchase, or participate in capitalism. Femininity has no originality. It has to be contrived; it has to be excessive. What that logic erases is that masculinity is also a capitalist construction.

Guernica: You’ve spoken about how capitalism and the state always want to colonize movements, but that the trans and queer movements seem to resist that colonization. How do you navigate that? How do you find allies when your allies might colonize you and pull you into the state?

Alok Vaid-Menon: That’s, like, my life’s question.

Janani Balasubramanian: You find friends, not allies. I think that’s the goal. You have to recognize which relationships you’re building for political utility and which relationships are actually going to support you, regardless of whatever political condition or thing we’re advocating for. Those are the sorts of discernments we need.