Before Zack Snyder, there was Joel Schumacher. Both directors exhibit a certain essentialism to superheroes but in very different forks of the road. During production on 1997’s Batman & Robin, Schumacher (in)famously quipped, “They’re called comic books, not drama books.” This line of thinking produced a film, a superhero film, redolent in neon, featuring costumes festooned with nipples, faux-abdominals, magnificent codpieces, and cinematography that lingered over the human body’s curvature lusciously, almost as explicit as any painting by Titian or Botticelli.

This project, the second in Schumacher’s Batman series, was to be his last. And his essentialist formulation of what superhero movies should be has long been mocked, derided for not being “mature” or “serious” enough for mainstream tastes. Above all, as many fans claimed, his Batman wasn’t their Batman. So bad was the reception that it wrecked the character for almost eight years, precipitating a dearth of appearances by the Caped Crusader on the big screen between 1997 and 2005.

Of course, delays between superhero films means an asset lies dormant i.e. money isn’t being made. The quick turnaround of franchises, such as Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man 3 (2007) begetting Marc Webb’s The Amazing Spider-Man (2012), Ang Lee’s Hulk refreshed as The Incredible Hulk (2008), Tim Story’s Fantastic Four (2005) and Fantastic Four: Rise of the Silver Surfer (2007) rebooted as Josh Trank’s Fantastic Four (2015), and, the illustrative example, Schumacher’s entry giving way to Christopher Nolan’s Batman Begins.

On March 25th, Nolan will give way to Snyder. Batman will appear again, along with pal Superman, in Batman V. Superman: Dawn of Justice, and fight each other because that’s what’s supposed to happen. Based on the trailers and marketing and the ostensible prequel, Snyder’s Man of Steel, this looks to be a grim affair.

“comics are words and pictures. You can do anything with words and pictures.”

No superhero spectacle escapes this rapid reinvestment, parlaying past cultural capital into newer, more broadly appealing installments. The superhero film originator, Richard Donner’s bright, corny Superman (1978) came back as Bryan Singer’s drab, dour Superman Returns (2006). Even forgotten, misguided entries, like 1990s hokey, B-grade Captain America, returned in 2011. Television, too, does this, turning the Tim Burton tinged, Danny Elfman scored, short-lived The Flash (1990-91) into today’s ongoing The Flash, currently on The CW.

Partly this tendency comes from the source material: superhero comics, predicated, as they are, on the premise of never ending struggle. Their very serialization makes endless chains of reboots and reimagining not just a tic, but part and parcel of the whole package. More than that, however, superhero comics are, as all comics are, the intersection of text and image. As famed comic artist Harvey Pekar noted, “comics are words and pictures. You can do anything with words and pictures.”

Yet, in superhero films, it seems you can’t quite do anything, or, more accurately, anything falling beyond what cash deems worthy.

Yet, in superhero films, it seems you can’t quite do anything, or, more accurately, anything falling beyond what cash deems worthy. That essentialism voiced by Schumacher, rejected by audiences, has returned in an inverted form embodied by Snyder. These books are now drama books, not comic books, and their filmic interpretations reflect that. As superhero films have become bigger and bigger, ballooning budgets, massive box office receipts, flattened by the tastes of a global marketplace, the range of what a superhero film can be has narrowed. This trend is not unlike an oft-quoted observation made by famed linguist Noam Chomsky: “The smart way to keep people passive and obedient is to strictly limit the spectrum of acceptable opinion, but allow very lively debate within that spectrum….”

Since Batman & Robin’s demise, and especially since 2008’s The Dark Knight, superhero films have increasingly fallen into a narrow spectrum of what’s acceptable and what isn’t, as if there’s a secret formula that studios have finally cracked. Consider the visual similarities between X-Men, X2: X-Men United, Fantastic Four, Batman Begins, X-Men 3: The Last Stand, Superman Returns, Fantastic Four: Rise of the Silver Surfer, The Dark Knight, Iron Man, The Incredible Hulk, Iron Man 2, Green Lantern, Captain America: The First Avenger, The Dark Knight Rises, The Amazing Spider-Man, Iron Man 3, The Avengers, Man of Steel, The Amazing Spider-Man 2, Captain America: The Winter Solider, Avengers: Age of Ultron, Fantastic Four, and glimpses of the impending Batman V. Superman: Dawn of Justice, Captain America: Civil War, and Suicide Squad. This omits numerous films that are tangentially linked in visual style (Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man trilogy, Daredevil, The Punisher, Catwoman, Punisher: War Zone, X-Men Origins: Wolverine, Thor, X-Men: First Class, The Wolverine, Thor 2: The Dark World, Guardians of the Galaxy, Ant Man) but, for argument’s sake, let’s stick with these larger tent poles.

Although most of these films come from a few directors (three from Christopher Nolan, two each for Jon Favreau, Tim Story, Joss Whedon, the Russo Brothers, and Zack Snyder, respectively) the visual bleed over between them is immense. All feature elongated (some would say excessive) action scenes, typically the climax, set either at dusk, ruddy sunlight, night, or in darkened, interior conditions. The color blue is favored, either as a visual filter or explicitly in effect shots, usually paired with flame or other orange-ish light source, providing the complementary pairing of blue/orange, featured prominently in so much marketing material. Many films involve blue lasers shooting into/from the sky. Starting with 2008’s Iron Man, end credit scenes multiplied, cross-pollinating studios.

Certain signifiers are satisfying, color arrangements seduce our brains, and darkened conditions often mask the rougher edges of compositing special effect shots.

Our protagonist’s costumes, the calling cards of superheroes, are either CGI or body sculpted like Grecian armor, very similar to each other, but quite distinct from the traditional spandex of Adam West, Lynda Carter, or Christopher Reeves. Color wise, everything’s been knocked down a shade. Red has become scarlet, blue is royal, yellow is gold, gray is black. As comic writer Warren Ellis in Do Anything remarked about Jim Lee, currently DC Comic co-publisher, an artist that launched a thousand imitators, who was being pushed into redefining Batman in late 2002 but ended up doubling down on the traditional depiction of the character, “Don’t look for new ways to make marks and shape figures, Jim. Batman wouldn’t like it.”

Of course, film is a visual medium and the duplication of visual vocabulary is to be expected re: the appetites of audiences and demands of the market. Certain signifiers are satisfying, color arrangements seduce our brains, and darkened conditions often mask the rougher edges of compositing special effect shots. However, tonally, the similarities are even more striking.

Despite doses of levity in James Gunn’s Guardians of the Galaxy, Joss Whedon’s two Avengers films, or Shane Black’s Iron Man 3, post-1997 superhero movies, by and large, are grounded, serious, and, above all, striving for realism. Even those aforementioned entries still root their subject matter or piggyback on tropes from other film genres. These are movies, largely science based, beholden to objectivity, rationality, and logic, which are, invoking Heath Ledger as the Joker, interested in bringing superheroes “down to our level.” A key criticism of The Dark Knight Rises was Bruce Wayne’s sudden appearance in Gotham after detention in a prison of indeterminate location, presumably the Middle East. That’s not logical, fans said. Yeah, it’s not, but neither is a reclusive billionaire combatting criminals in an S&M bat costume. Rather than being labeled bad, dull, or derivative, superhero films are more frightened of being seen as less-than-serious, not grown-up. Drama books, indeed.

However, this drive to standardize and flatten superhero films is intertwined with notions of ideology and the role of the artist.

However, this drive to standardize and flatten superhero films is intertwined with notions of ideology and the role of the artist. For me, the most intimidating (and impressive) part of any superhero film is not the villain’s plot or the extensive scenes of action. No, what always staggers me is during the end credits, after actors and directors and writers, the giant wall of effects artists: white lettered names rolling past, illuminating the theater with a vicious intensity. The organization and coordination is awe-inspiring but it is also a bit of a downer considering that so much talent and energy is devoted to content that is so similar and undifferentiated from each other.

Jack Kirby, a legendarily prolific artist who actually birthed a scary quantity of characters, defined much of the vocabulary for superhero comics. His distinct style (kinetic, blocky, exaggerated) has been aped and mimicked beyond tally. Indeed, his work, in a diluted form, became the signature look of Marvel, so much so that artists were directed by editorial to produce work in “the Kirby style,” something he deeply rejected. When he decamped Marvel for DC in 1970, Kirby was given opportunities to indulge, to revitalize the line of a once dominant publisher. Do anything, essentially.

The artist opted for a low-tier title, Superman’s Pal, Jimmy Olsen, as a backdoor to kick off his long gestating Fourth World saga, a series of interconnected titles (The New Gods, The Forever People, Mister Miracle) that would form an entirely distinct mythology for a key twentieth century art. So Everest in dimensions was the hype that “KIRBY IS HERE” was blazoned along the masthead. Kirby got to script his stories, had his choice of inkers, and escaped the editorial control that, partially, drove him from Marvel. What he didn’t get however, was Superman’s head.

Body, backgrounds, every other character was fully under Kirby’s control and direction, left to the artist to decide. The head, spit curl and all, wasn’t his to work with. He drew his pages with a decapitated Superman, resembling a chicken sans head. Because his style was deemed “off-model” a longtime company man was brought in, Al Plastino, whose talents hadn’t evolved along with the medium, to finish off Kirby’s Superman to better reflect DC’s house style and the mountains of merchandizing that had largely supplanted the comics as the center of concern. Warren Ellis remarked that this decision “speaks to a management notion that artists are interchangeable, artists are flunkies, artists may not speak in their own voice even when servicing corporate assets for a passionate audiences, artists are just cogs and wheels and should shut up.”

Thank you for Batman, Bill Finger, but, please, kindly go away.

This incident, Kirby not allowed to draw Superman’s head, might be a relic of a less enlightened time, when comic artists were treated as temp labor, who scribbled and toiled and created and were told to take a hike after it all. Thank you for Batman, Bill Finger, but, please, kindly go away. Same with the horrendous treatment meted out at Superman’s creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster. But such trends continue to this day, only transfigured to digital cinema. For those shocked by Edgar Wright’s departure from Ant Man mid-production over creative differences, or Joss Whedon turning down another Avengers film, citing exhaustion and purported behind the scenes friction, or Ava DuVernay turning down Marvel’s upcoming Black Panther because it really wouldn’t be her movie, or the mess that was Josh Trank’s Fantastic Four due to countless studio interferences, hinted at via his Twitter feed, don’t be.

Superhero films, like superheroes, can be anything. Often, they end up being quite the same, confined to a tight spectrum. Whether that’s the gender or race of the characters and the actors that portray them, or the tone and style of the films, the similarities are staggering. If so much money is being spent (Avengers: Age of Ultron’s budget topped out near $280 million), enabling filmmakers to do, literally, anything, why is so little difference being done?

What this reflects is something approaching an ideology. It’s not unlike defenders of neo-liberal economics who stress, fervently, that they are not ideological, not biased, that their proscriptions and predictions are neutral, objective, level-headed, a reflection of historical fact, and not some sort of tightly clutched preference that benefits those who cut the checks. Audiences want grounded, serious, similar superhero films, we’re told, because that’s what the market wants. Superman has been deemed corny, dumb, a character not worthy of relating to by the higher ups. That’s why he lost his over the suit undies in Snyder’s Man of Steel. That’s why he must fight Batman, the most profitable character, in a new movie, also made by Snyder. That’s what the people want.

But there’s a way out stretching back to Kirby and Ellis. Do anything. Consider Deadpool. It’s a hard R movie. And it has made bank, one of the highest grossing R-rated films of all time. That was a major risk on Fox’s part. It stepped out of the narrow PG-13 confines, eschewed the blue laser, lowered the stakes, and poked fun at the superhero establishment. Though I didn’t particularly enjoy this film, I understood its goals and why it mattered that it was different and unique. This was a separate space that wasn’t for everyone and it didn’t have to be. It put a pie in the face of superhero film ideology and, again, grossed big because it embodied the do-anything ethos of the best comics. New space should have been blasted wide open.

Studios have reconsidered upcoming releases. Sadly, given Deadpool’s success, they seem to have absorbed the wrong lessons, as director James Gunn noted. The difference is now looked at as a new norm. Batman V. Superman: Dawn of Justice has an R-rated cut for home release due to Deadpool’s success. DC’s Suicide Squad is just on the cusp on an R-rating. The same is being whispered about Marvel’s Captain America: Civil War. A third reboot for Fantastic Four might also follow this emerging ideology.

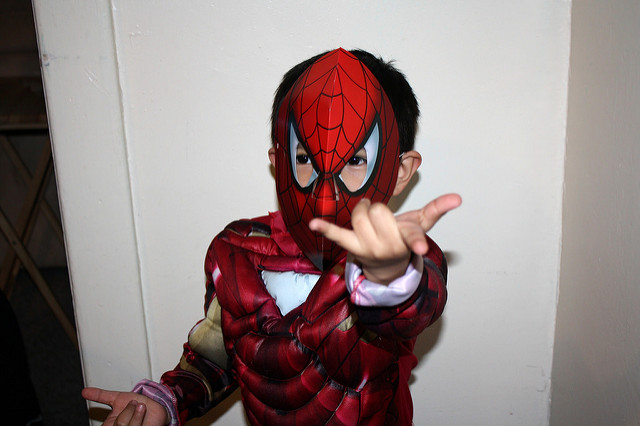

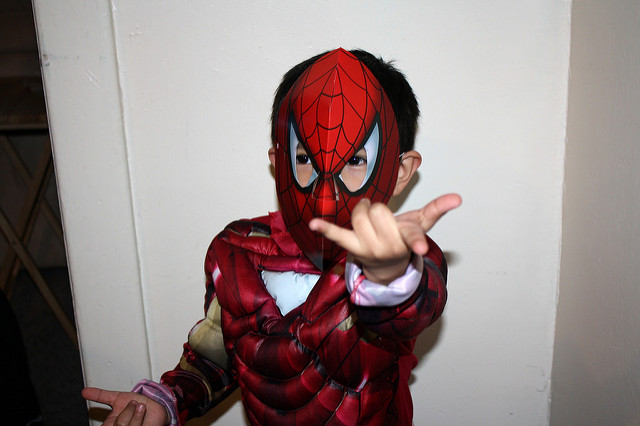

There’s nothing wrong with an R-rating. However, producing every superhero film as such discounts the actual content. It’s an ideology that subverts the actual source material, flattening difference in favor of profits. Superheroes were commercial products from day one. Yet, the inventiveness of the artists are what people latch onto. These characters, and the work of writers, artists, colorists, inkers, letters, editors speak to us in ways cultural, ethnic, racial, more than simple capitalist ideology can, enough to where protestors in Cairo’s Tahrir Square sported Superman t-shirts, Ta-Nehisi Coates, writer of an upcoming Black Panther revival, reflected on Spider-Man’s marriage, and a school principal in Taiwan addressed students in an Iron Man suit. These characters encourage thousands of people to don costumes and attend conventions, adding their own twists, doing anything they please. The do-anything ethos of superheroes penetrate the planet more than markets can ever hope to.

Batman V. Superman: Dawn of Justice appears to be the ur-form of superhero film ideology by the studio. The film might be a fine one. It looks expensive. But Snyder’s work isn’t original, nor will it capture what makes comics interesting, or the few superhero films that work. But, like any problem, acknowledgement is necessary to allow these characters to fly once more.