Growing up as a middle-class Indian in the 1990s and 2000s, I had access to two very different kinds of comic books. On the one hand, the Amar Chitra Katha imprint produced hundreds of slim volumes drawn from Indian mythology. On the other, there were western comics with their charming imperial adventurers (Tintin), war-mongering ancients (Astérix), and young American consumers (Archie). Though they represented different cultural universes, these two bodies of work shared one trait: they had absolutely no connection to my life. Indeed, I never imagined the comics would be more than a fundamentally escapist medium for me.

That all changed in 2004 with the publication of Corridor, Sarnath Banerjee’s debut graphic novel. Rendered in a mixture of photographs, drawings, and text, Corridor followed the lives of three ordinary men who whiled away their time in a second-hand Delhi bookstore. The world it depicted—one of roadside hustlers and garish billboards, of liberated college students and their conservative landlords, of trendy parties and shady markets—was, for the first time, entirely familiar.

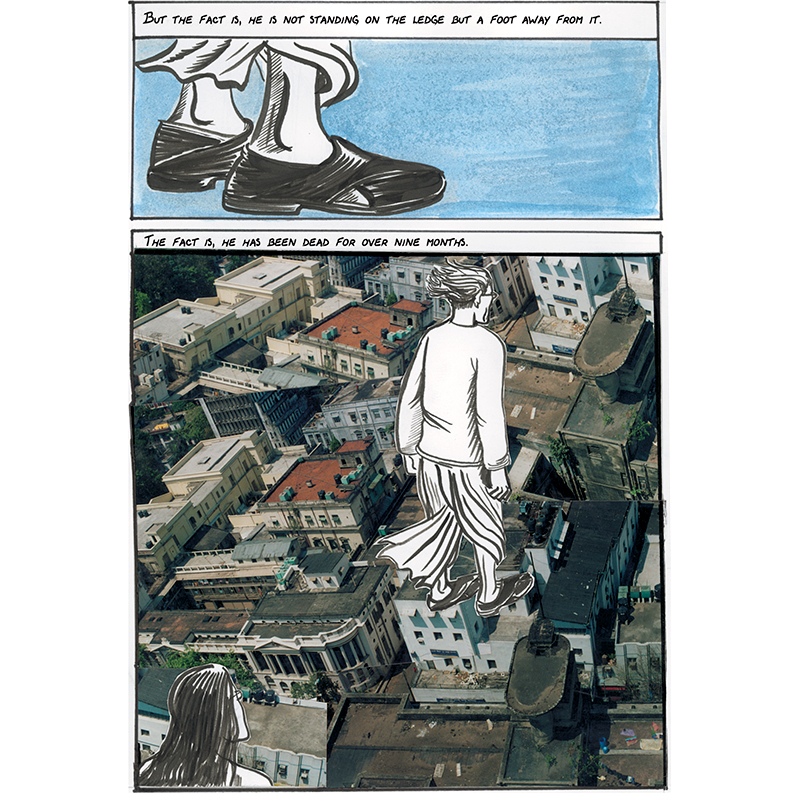

Though rooted in the local textures of Delhi street life, Corridor was driven by an assured, cosmopolitan sensibility. Banerjee made it his business to gleefully make collide east and west, culture and kitsch, high and low—to make Baudrillard wash himself with the local Liril soap. His early aesthetic, in which characters drawn in a sparse western comic style are often superimposed on billboards and street photographs of Delhi, brilliantly mimicked the mentality of post-colonial urbanites who straddled different cultures.

Corridor didn’t make him millions (the graphic medium has yet to find a commercial footing in India) but it brought Banerjee critical acclaim, as well as a cult following amongst high school and college students, your present correspondent included. Corridor also paved the way for other Indian graphic novelists to have their work published. Three years later, Banerjee followed it up with The Barn Owl’s Wondrous Capers, a more ambitious project that used the symbolic figure of the wandering Jew to examine forgotten (and perhaps fictitious) episodes from Calcutta’s colonial history. Like Corridor, Barn Owl was bracing in its cosmopolitanism.

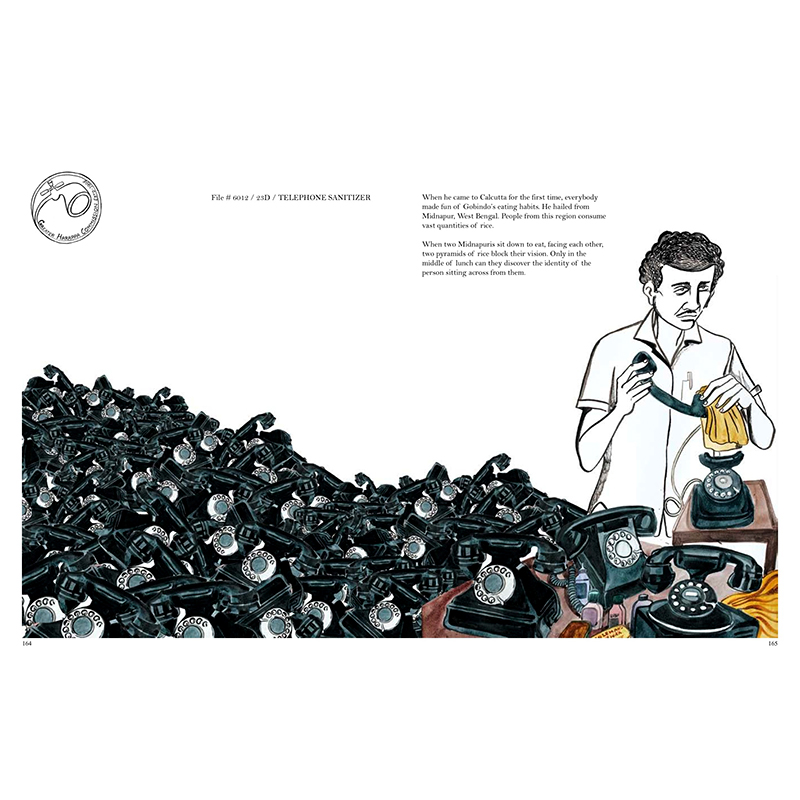

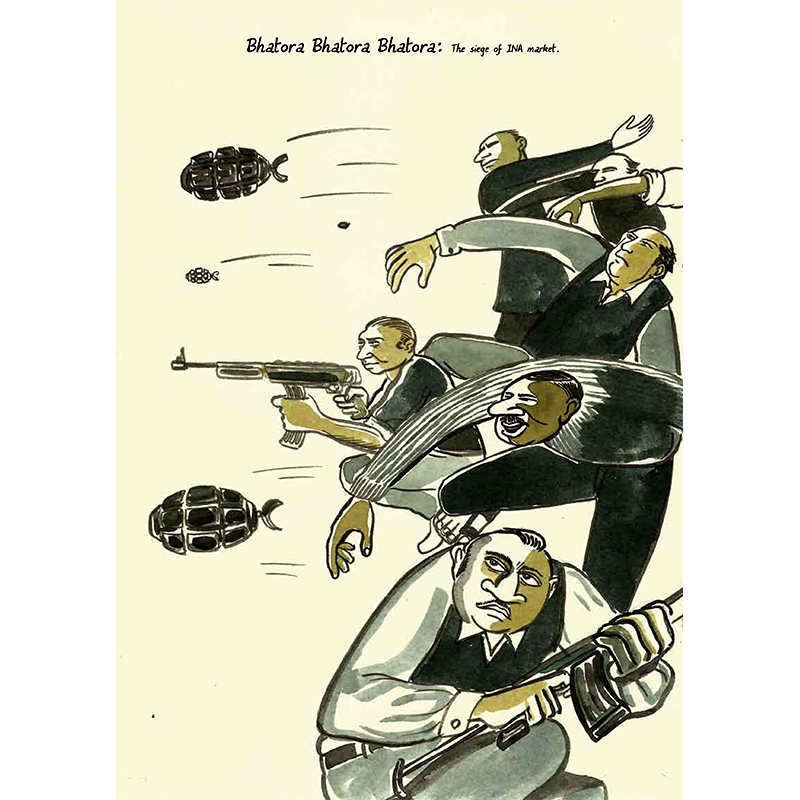

In 2011, Banerjee released the The Harappa Files, an encyclopedic collection of illustrated micro-stories featuring middle-class Indian characters. The book was obliquely inspired by early Mughal and eighth-century Iranian sources, and marked a stylistic breakthrough for Banerjee. Where Corridor and Barn Owl included a mashup of visual styles—from political caricature to zany punk to rough pencil sketches—Harappa unfolded in a careful sequence of lush, atmospheric watercolors, entirely appropriate to its darker political matter. This January, Banerjee published All Quiet in Vikaspuri, a dystopian, prescient (and very funny) story that depicts Delhi in the throes of a water war fought across class lines.

While his books vary in terms of formal structure, Banerjee’s central concerns remain constant. Time and again, he delves into the psyche of middle-class India—that fraught zone of consumerist aspiration, post-colonial angst, and conservative leaning—and emerges with reports on its citizens’ yearnings and fears. Yet Banerjee’s books are never didactic. He has a special affinity for the ultra-rich deformed by their own money and addresses dark episodes from colonial history, but his take on these subjects is sly, playful, and at times even absurd.

It helps that Banerjee draws well—so well, in fact, that he’s become a visual artist in his own right over the past few years. His images have been displayed at various international biennales and at the MoMA. In 2008, Banerjee was even commissioned to design billboard art for the London Olympics, a series he titled A Gallery of Losers.

Banerjee grew up in Calcutta and Delhi, but has been living in Berlin for the past five years. This interview was conducted over two long Skype sessions, one early in the morning EST, one late at night BST. As an interlocutor, Banerjee is maddeningly free-spirited. Instead of answering my questions, he’d use a phrase or idea from them to set off on a digression that, like his books, nimbly jumped from one topic to another. Even if I had wanted to, there was no stopping him once he set off like this.

—Ratik Asokan for Guernica

Guernica: You were a pretty big deal in my high school. Students put on plays of both Corridor and The Barn Owl’s Wondrous Capers.

Sarnath Banerjee: You went to Rishi Valley, right? I was very honored by that. It’s more meaningful to be accepted in certain places as compared to others. There are different reasons why people write: for themselves, or for other writers, or to get prizes, or keeping an audience in mind. In my case, it felt really nice that a certain type of readership read the book and liked it, even though my readership is not as wide as certain popular books.

Only a very specific kind of writer keeps their reader in mind while working.

Guernica: Whom do you imagine as your ideal reader?

Sarnath Banerjee: Only a very specific kind of writer keeps their reader in mind while working. Such writers don’t want to irk their readers; they don’t want to challenge their readers; they want to produce exactly what their reader expects them to produce. I’m not like that.

I want to make sense of things, to understand the world, but my work is never really instructional. I have no wisdom to impart or give, so I think my dream readers would be people who just use the book as an excuse to get into their own cycle of thoughts. The book is just like a map. It’s just a jotting-down of things that you can interpret in your own ways.

My books also serve as archives of thoughts and emotions, like a tonal history that captures how I felt at a certain time of my life. It’s not very informational. You’re not going to get comprehensive knowledge about the Han dynasty of China or about India’s Emergency. But you might learn how one person felt about the Los Angeles Olympics.

Guernica: What drove you to become a graphic novelist in the first place?

Sarnath Banerjee: I used to make documentaries for Business India TV. I made a few, and they were probably quite mediocre. The problem was that I felt constrained by the conventions of industry, although BIT, at that time, was one of the most adventurous TV channels. All the stories I wanted to do were considered unimportant and banal by others. They were rich with tonal detail, but people said they were just an exercise in tonality.

Guernica: Could you give an example?

Sarnath Banerjee: In Bhopal I met a man who, on the night of the tragedy, had conducted hundreds of autopsies. And from the gas trapped in his lungs he got himself gas-affected. Now, this man had an amazing private archive that he called his biodata. This archive consisted of laced cigarettes, forced-aborted babies, a finger chopped as a kidnapper’s ransom, a knife that was used with such force that it bent—things he had collected from years of forensic work. I was very interested in that kind of detail. The man himself used to wear this very nice double-breasted suit. Every day I met him, he would come in this pastel-colored suit.

People are infinitely more interesting than characters that I come up with.

Guernica: He sounds like a character from your books.

Sarnath Banerjee: People are infinitely more interesting than characters that I come up with. Because the characters I come up with are basically combinations of people I’ve met. Combinations. You select certain details, that’s all.

Anyhow, this man required an entirely different treatment—he’s a film in himself. But the film wouldn’t have a script point. A broadcasting guy would say, “That’s all very fun. It’s like a nice drawing-room conversation. But we can’t see the point of doing this.” People are interested in more relevant stories. In big events. But I’m not interested in big things; I’m interested in the smaller details of life.

Likewise, if you planned to make a film on Delhi, it had to be something ‘big’ about Delhi. You couldn’t make a film—like Corridor—that was just about people who sat around Connaught Place, endlessly. You couldn’t make a film that simply questioned what happened in their heads. You couldn’t make a film that followed a common hustler, a property agent who shows people houses everyday. But there’s nothing common about a common hustler–property dealer. He is interesting; he’s a dream maker; he makes you imagine a household, and the sunlight falling at a diagonal through the window. He makes you imagine drinking Earl Grey tea while looking out at a golf course.

This hustler is creating a fantasy, and I’m interested in the tonal details of that fantasy. I’m also interested in the secondhand bookseller who is an autodidact, who knows everything from lightweight boxing to chemistry to Bhatnagar’s chemical experiments. I wanted to create the full texture of a city, an encyclopedia of characters. But that wasn’t possible in a film, because it had no ‘plot point.’ And that’s what drew me towards graphic narratives.

Guernica: Interest is one thing, execution wholly another. A close friend and I embarked on several ‘Sarnath Banerjee–style’ graphic novels in high school; we never got far. How did you end up actually writing the book? I mean, for kids of my generation, Corridor was some mysterious form of contraband. It came out of nowhere. India’s first graphic novel!

Sarnath Banerjee: Aside from working on the documentaries, I was pitching these graphic ideas to people, but they were going nowhere. Then, finally, I got a commission from this gentleman named Rajib Sarkar who was the editor of—he has disappeared now by the way, he’s absolutely disappeared from earth—Gentleman Magazine. Sarkar was the biggest bibliophile I’ve ever met. He worshipped books. And at that time in India, the early 90s, a magazine could actually run features like “5 Canonical Texts Retold in a Bombay Setting.” So, for example, The Metamorphosis would be happening in Borivilli [a suburb of Bombay]. Each story would be done by a writer and a cartoonist, and I was commissioned to draw one story.

Rajib introduced me to a writer who later became one of my all-time favorites: Isaac Bashevis Singer. I was to do the visual treatment for a retelling of “Gimpel the Fool.” The Indian writer I was paired with set the retelling in a Parsee neighborhood. I didn’t know much about how the Parsees of Bombay lived. In fact, I didn’t know much about Bombay either at that time. So to learn about them, I befriended Sooni Taraporevala. Do you know her? She is the writer of the films Mississippi Masala and Salaam Bombay. She also made Little Zizou. She’s also an award-winning photographer; she made this book called The Parsees.

Guernica: I’ve seen that.

Sarnath Banerjee: Yes, everyone seems to have. So Sooni gave me a lot of the photographs of Bombay Parsees. She has been such an important influence in my life. A lot of my visualizations are actually like Sooni Taraporevala’s visualizations. She has the ability to use her camera to probe into the deeper, funnier, more eccentric aspects of people. She’s amazing. You should see her work. So I looked at her photographs, tried to learn from them, and did the project.

And I was deeply satisfied with my work. The process was very important, because it made me realize that, fuck, man, this graphic medium will allow me to explore a new subject every day. It’s going to give me an excuse to get into different people and different ways of looking at things.

After that I kept on doing comics, and no one would publish them. I think it’s really good not to get published. It sounds crazy but it’s true. People want to get published very soon, but the moment that happens, you lose a bit of your originality. Once you publish, you are always doing things made-to-order. You stop being a weaver and become a tailor. You are tailoring things to suit other people’s fashion. I did a lot of very interesting work during the time I remained unpublished. Then one day I got the MacArthur grant.

Guernica: You got a MacArthur grant before your first book!

Sarnath Banerjee: Yeah.

Guernica: On the basis of a few clips?

Sarnath Banerjee: No. It was a combination of luck, the documentaries I had made—some people thought they were nice—and the strength of the proposal. This is not the MacArthur “genius” award that is given to American citizens. This is something similar but given to Asian people. I was in amazing company that time: Vikram Patel, who is one of the most important experts on depression, he’s a psychiatrist; Amar Kanwar, the artist. It was a great gang, and the MacArthur helped us a lot. Remember, in India we don’t have a lot of arts grants like in the west. I also got tons of money. Money I didn’t know what to do with.

Guernica: When you say tons of money, do you mean by an artist’s standards or a CEO’s standards?

Sarnath Banerjee: An artist’s standard—which, I suppose, is equal to what a CEO makes in a month. I went completely bonkers with the money. I worked and worked. But I didn’t have the confidence to draw. I didn’t have the confidence for a whole graphic novel.

So I took my ideas to Orijit Sen—who, by the way, actually wrote India’s first graphic novel, River of Stories, back in 1994; it was a graphic novel, but it wasn’t marketed that way—hoping that he would illustrate them. I actually went all the way there from Delhi to Goa, where he was living at that time. Now Orijit was phenomenally helpful, and we spent a lot of time working together, but for some reason the collaboration did not work. Nevertheless, he was instrumental in encouraging me to draw.

Then I drew it myself. I started at the deep end. I learned while writing the book. I started drawing all the time after that. Like a maniac. My ex-wife recently told me that when she was cleaning up our house she found trunks—I had forgotten about this—trunks and trunks full of notebooks on which every surface had been drawn. I drew everything. I drew toasters, air conditioners, chairs, people and flowers. I was a maniac. I drew, drew, drew, drew, drew. And that’s how I learned. Purely by doing. In Japan there’s a phrase for it, it’s called aware karada, which basically means learning through your body. You practice something to the point where you don’t think anymore about it. It just comes out. The brain and hand barrier is absolutely taken out. So I think now I don’t think about my drawing at all. It just comes the way it comes. Another thing that was good about working in this entirely new medium—new to India at least—and not getting published was that it makes you learn everything from scratch. Which is why I feel that every graphic novelist from India—Amruta Patil, Vishwajyoti Ghosh, Orijit Sen, Appupen—is phenomenally original.

Anyhow, Corridor came out of the MacArthur, and after countless rejections from publishers, it was finally accepted by Penguin.

As a non-western artist, you have to ask yourself a question fairly early in your life: do I want to become a bridge maker, do I want my culture to be understood by the west? I have no intentions of doing such things.

Guernica: Corridor is about the lives of three people from very different social backgrounds who happen to visit the same secondhand book dealer in Delhi. The loutish Anglophile middle-class intellectual, Brighu, I understand, but how did you come to write about Digital Dutta, a Marxist IT guy, and Shintu, who comes from a much less westernized background?

Sarnath Banerjee: I have been a loiterer all my life. I’ve met these people. The truth is, you have to lead a certain lifestyle to write a certain kind of literature. Corridor comes out of my sustained experience with Delhi. I think what you’re getting at is less a class thing and more a western versus non-western thing. Because Corridor’s protagonists are all just middle class. You relate with Brighu because he’s an Anglophile, and, as we all know, European and American sensibilities are not underexpressed in our culture. If anything, they are overexpressed, which is why you find Brighu familiar. And the reason you might find Digital and Shintu a little unfamiliar is because I’ve not tried to explain them.

As a non-western artist, you have to ask yourself a question fairly early in your life: do I want to become a bridge maker, do I want my culture to be understood by the west? I have no intentions of doing such things. I’m fine being a little strange to a non-western audience. It doesn’t bother me if my book doesn’t change a generation of American readers, like Jhumpa Lahiri’s books are doing, or Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s books are doing. In order to write universal literature, you have to iron out a lot of particularities. And I’m not interested in making things friendly reading for Americans. We come from huge landscapes: India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh. If you put that world together, it’s a lot of people.

Who gives a fuck about New York? What’s great about being in one small section of the bookshop in the Strand? I don’t think it makes me feel any culturally greater. I think that age has gone: of having my work understood in New York, or by an Anglophile Indian for that matter. It’s not my intention to be understood. I will continue writing for a readership that is fundamentally local. Because if you want to produce universal writing, you run the risk of losing your local knowledge. Your views are so universalist that the street aspect disappears.

Guernica: And the street is very important to Corridor. Especially the street hustlers.

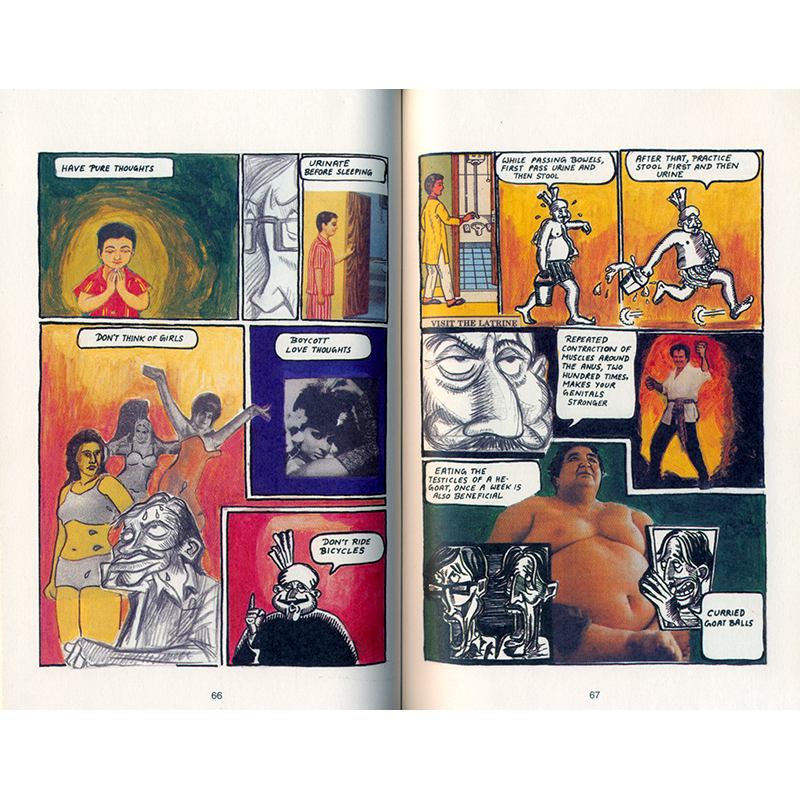

Sarnath Banerjee: Hustlers, yeah. Hustlers are lovely people. They have so much personality. They are such charismatic people. But we are all hustlers. Whom I’m especially interested in are the downgraded hustlers. The juice wallah who is also a property dealer who will also fix your erectile problem. These downgraded hustlers are the most charismatic people.

Guernica: You portray them so well: without sentimentality, and yet with great warmth. How did you come up with your unique visual idiom? I know no one who captures everyday Indians like you do. Who were your early visual influences?

Sarnath Banerjee: Everything you draw is influenced. It’s like yogurt. You need a little bit to start the next batch. So there were a lot of people. Taraporevala has been a very strong influence because she had the ability to use her camera to probe into the deeper, funnier, more eccentric aspects of people. Her photos are so narrative. I absolutely love her work.

If I start listing my influences our interview will never end. But I’ll try to tell you some people whom I can immediately think of. There’s of course William Blake, and Goya. And Albrecht Dürer. These are the westerners that I’m absolutely fascinated by. Tintin, without any doubt. In terms of cinema, Alain Resnais; his visual technique, his way of telling stories was very important. Night and Fog is an amazing film.

By the time I had acquired enough confidence to work on a local idiom, I got really interested in a lot of local stuff, like Sai Paranjpye, who made Chashme Buddoor. Basu Chatterjee. Their cinema I started liking. So not just the highbrow stuff like Satyajit Ray and Ghatak and all. I got interested in people who really made it their business to make their art available to people.

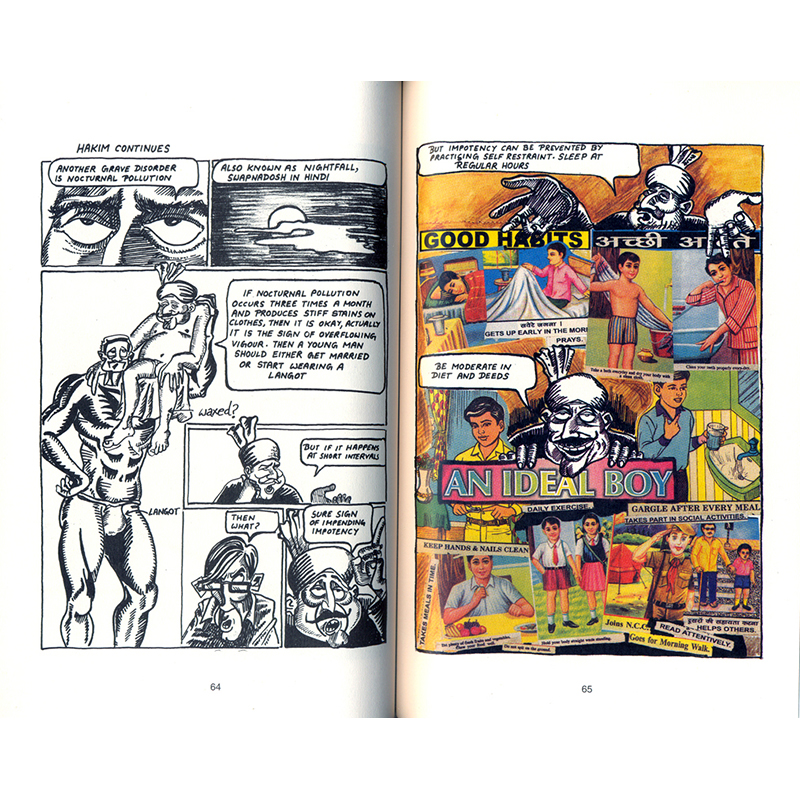

The whole idea is to make knowledge available without hiding behind big names.

Guernica: Another thing that strikes me about Corridor, and the rest of your work, is how easily the highbrow stuff sits with the lowbrow: like, Benjamin will share a page with a hustler selling sketchy aphrodisiacs. Baudrillard and Phantom comics are evoked in the same discussion. You incorporate Cartier-Bresson and Vigée Le Brun without acknowledging their names.

Sarnath Banerjee: I like what you say about the heavy knowledge sitting beside things that are almost silly or banal and profane. That tonality is partially shaped by Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift, who in the seventeenth century started the Scriblerus, where they postulated that the only way one can display learning is by playing with it. Because the truth is that there’s something embarrassing about displaying heavy knowledge. You feel sort of Bengali, sort of annoying.

Also, quoting big thinkers—though they certainly affect my thinking—reminds me of being an MA student. And I don’t want to sound like an MA student. The whole idea is to make knowledge available without hiding behind big names. Maybe it is not a rejection. It is simply having the confidence to speak without having to quote people.

This also leads me to the difference between fiction and nonfiction readers. People who read nonfiction want to dispense knowledge. Even if they don’t mean too, it comes across in their writing. They know everything about Siachen [a glacier in the Himalayas], they know everything about psychology, they want to tell you why Syria is happening. They’re constantly trying to find a solution to things. Fiction readers, on the other hand—and I’m one of them—don’t have this compulsion. They don’t have an arrogance which leads them to display their knowledge. Because often there isn’t any knowledge that you acquired. What fiction does is bring you closer to the essence of truth, as opposed to simply giving you the truth. And there’s no knowing truth. Truth seekers are all charlatans. You can only feel the truth of something. Blake, for example, had a sense of heaven and hell. But he never really tried to postulate what they were.

Guernica: Barn Owl is structured as a false history. I say false, but most people—or me, at least—have no idea which parts of that book are true, and which parts are made up. You evoke the historical era so well. What got you so interested in history?

Sarnath Banerjee: I find the historical method very interesting. Philology. The idea of reading different texts and creating an interpretation of them—history is in its interpretation. As you know, that’s an important issue currently in India. History textbooks are being… you already know this. [In 2014, the Gujarat state government introduced several dubious books into its elementary school curriculum. Written by right-wing Hindu nationalists, these books freely merged myth and history, and even claimed—citing the Hindu epic, the Ramayana, as primary evidence—that airplanes existed in ancient India. Prime Minister Modi is from Gujarat and used to be its chief minister. He even wrote a preface to one of these ‘textbooks.’]

I feel history is more of a story than a lesson. Okay, I know this idea of presentism: this idea of constantly evoking the past to justify the present moment. A lot of people will tell you, “history is how we got here.” And learning from the lessons of history. But that’s imperfect. The Russians tried to learn from the lessons of Napoleon and decided—after Lenin died—to evict Trotsky because he was too willful a man. Their solution was to give the top job to an ambitionless bureaucrat. That’s how they ended up with Stalin! So if you learn from history you can do things for all the wrong reasons.

This history as presentism is not entirely true. I agree with it, to an extent, but I’m not interested in it. I’m interested in history because it’s a discipline that requires a lot of effort from the imagination. You need to put in a lot of imaginative effort to figure out how people lived in an era that is not yours. And in that understanding of people from a different era, I feel, is an important gateway into humanity. Because you understand human behavior. In order to understand humanity, history is important.

And I like historians. They have good interpretive skills. They are also often great storytellers. In fact I’m more interested in historians than I am in history. Which is why I’m planning this history biennale.

Guernica: You’re setting up a biennale for historians?

Sarnath Banerjee: It’s a sort of joke. But all my projects begin as jokes. I shared the idea with Kamran Asdar Ali, who teaches at the University of Texas (he heads the South Asia Institute there, and is also a remarkable scholar and anthropologist) and he told me, “tum bade joke karte ho” [you joke a lot]. So I said, fine, I’ll put in some money. And now he’s going to put in some money so the biennale stops being a joke. And then Vazira Fazila-Yacoobali Zamindar, who wrote this amazing book on partition, called The Long Partition, she invited me to come to Brown and start talking about it. So I’m raising money from all these people.

And then Gyan Prakash, a professor at Princeton, who wrote Mumbai Fables, which was made into a film called Bombay Velvet—he’s a rockstar historian, he joined. Then a few others from Columbia. These guys are all supporting the project. And I’m going to get ten historians to work with ten visual professionals, not necessarily artists—animators, illustrators, set designers, architectural model makers, fashion people, I don’t know—to give their research a form that you and I could read. Perhaps they can make historical sets.

This idea came from Barn Owl, of course. Because my historical research for that book didn’t just involve reading one text after another. It involved going to the British Museum India office and trying to figure out what twentieth-century guns looked like. What were dresses like then? In my line you have to do a lot of visual research. And research is so much fun! The seeds of the biennale idea came at that time.

I’m not interested in, and not capable of, direct politics.

Guernica: How do you think that historical research affected the next book, Harappa Files, which is a series of graphic vignettes about today’s middle-class India?

Sarnath Banerjee: I’m not interested in, and not capable of, direct politics. What I can do—I try to figure out the underlying principles. I’m interested in the psychological forces that divide us as a nation. What forces create this mass conservatism? Why is India’s middle class so conservative? Why are our parents so conservative? In order to be secular liberals do we have to be elite? These are the questions I was trying to ask.

Because you have to live with these people. They’re like bad cousins. Siblings gone astray. Harappa was my effort to understand the roots of Indian conservatism. Why is our default politics conservative? Why are we such a conservative country? And I never mentioned these questions—not once—in the book. The book doesn’t spell out answers to these questions. It just explores them.

Guernica: You say you’re not interested in politics, but the latest book, All Quiet in Vikaspuri, is very directly political. I mean, what could be more political than a dystopian Delhi torn about by a class war fueled by water shortage? In fact, I heard your original publisher backed off after seeing the manuscript.

Sarnath Banerjee: They called me a communist! But the truth is I don’t like direct comment. I’m not an activist-artist. It’s not that I’m not interested. I’m not particularly good at it. There are other people who are good at it. I’m a little more Zen about it. I would like to, you know, not pull out my sword from my scabbard. There’s an old samurai saying that the sharpest sword remains inside the sheath. Not that I’m the sharp sword, but still.

Having said all that, I should acknowledge that the Vikaspuri book grows out of my obsession with our country’s obsession with development. I’ve told you a lot about love and empathy and liking people, but I find it very difficult to relate to India’s new middle class. This very patriotic and neoliberal group that mixes religion and economics together. I find them very irksome. Very difficult to like. They are privileged, but they don’t want to talk about their privilege. It’s difficult to find poetry amongst these people. Some sort of hidden spirit of beauty. But I tried with this book to mock the South Delhi people. They don’t just have a caste system: they have instilled a caste system amongst their staff, from the driver to the gardener they have a caste system. It’s almost as if whatever they touch they turn into a caste system.

Guernica: I see your willingness to depict, to actually draw, non-privileged people as a political statement in itself. I mean, it’s a big middle finger to the standard middle class mentality that our drivers and maids are less than real people.

Sarnath Banerjee: Absolutely. Look at our country. We have had years of this Brahmanical hegemony; years of casteism; years of subservience to these ideas of growth and colonial practices. I now live in Germany, a society that’s relatively classless. Or at least it aspires to be classless. And being here you realize that, my God, India has sanctioned phenomenal injustices for years and years and years. And normalized it. And we are carrying that burden. And then some twenty-four people decide what nationalism is and tell us what to do. There is no sympathy in these right-wing voices. They are all trying to cover their backs. There is no understanding of what it means to be born into a class that has been denied basic human dignity for generations and generations.

We all grew up being told that Hinduism is a benevolent religion. Santana likes it. Madonna likes it. How can it be bad? “We Hindus are all tolerant. Hinduism is not a religion. It is a way of life”—I’m sure you remember uncles saying these things to you. But what Hinduism has achieved is a process of relentless othering. They have successfully dehumanized Dalits. Just because a person is Dalit, they say, he has another coefficient of suffering. That he is genetically equipped to deal with more suffering than you because you are princely and you can’t bear that kind of hardship. You can’t till land in 52 degrees centigrade. But those guys, they can.

Guernica: Both Corridor and your subsequent book, The Barn Owl’s Wondrous Capers, are very much concerned with cities—with their psychic and physical cartographies, from the fleeting relations between residents to the relationships between people and the city itself.

Sarnath Banerjee: The Scottish writer Alasdair Gray said that the city does not exist unless it’s been written about. I completely agree with him.

Imagine you own a roadside bookshop. You know where the books on geography are, where the medical textbooks are, where the SAT preparation books are, where Auden’s poetry is, where the contemporary South African fiction is, where the Tintins are. But if you don’t write this down, and you die, then the catalog dies. It just becomes a mess. It doesn’t exist as a catalog anymore.

Somewhere down the line, a city is a bit like that: a gigantic group of cluttered books. But a writer or artist has a way of making sense of it, of understanding how it is cataloged. The catalog lives in the writer’s head. Only if you write will the city-catalog be expressed. If you don’t, it slips into chaos.

And the most important part of a city is its people. In fact, people for me are like little cities. When you meet someone, it’s like you’ve found a new city to explore. You take a tram, visit the museums and operas and cafes. I have a genuine lust for people, and every time I meet someone I’m in absolute lament that I don’t know him better: that I don’t know what he does, what he thinks, what his secret world is, what his deepest passion is, what his victories and defeats are, what his sense of foreboding is, what his nightly dreams propelled by his state of digestion are.

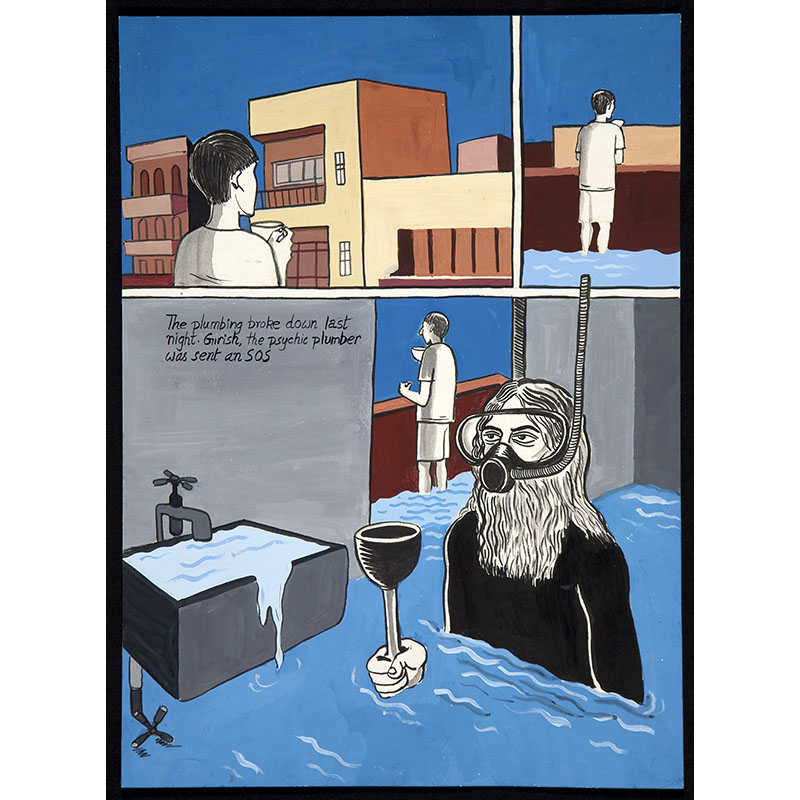

But I’m normally not interested in these posturers or these grandstanding big guys, who pronounce their opinions. In Delhi you find a lot of those types: mollycoddled from childhood, elite. Those guys are not very interesting. The people who are interesting are those you would not really think about, like a plumber. I’m obsessed with my plumber. Or the telephone cleaner who eats rice pyramids. The interest is not sentimental at all. It is just love. There is a degree of love involved. You just want to eat up all these people. Cannibalize them somehow. Because they are delicious.

Guernica: It’s wonderful that you love the everyman. I’m not sure if the same can be said about the everywoman. Indeed, women are woefully underrepresented in your work.

Sarnath Banerjee: It’s a handicap. It’s a serious handicap. I don’t know what to do about it. I’m mostly with women. Most of my friends are women. I’m phenomenally close to them and it doesn’t reflect in my writing. It’s very embarrassing and I cannot seem to come out of it. What I am doing now is a series for Vogue called Women I Know that’s basically an attempt to depict, in the standard graphic and text format, the personalities of women I actually know.

A lot of these historians I work with are women. Hopefully that changes things. It’s an issue, I understand. But I haven’t figured out an intelligent way to get more female characters into my stories, although I seem to hang out with them, and am mostly influenced by them. It’s a weakness, and I have to work on it. Thanks for reminding me.