When they came to strip us of Chuchu, Ma spat on the oficiales.

After Daniel ran away from home and hadn’t been back, it wasn’t exactly bread-and-butter dining. You could hear the vans parked outside of the building. They beat-boxed a masquerade, throwing a fog of party bus techno lights, and Chuchu would soon be swerving on that stretch of highway that crawled its way towards San Juan.

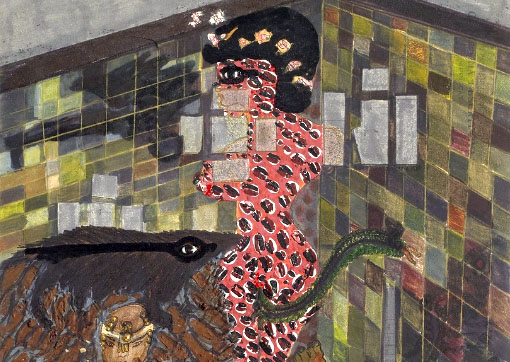

He sat cornered, roasting on the barred balcony as the sun ventilated its primetime special in el barrio. El Casero, as he was known by us—lanky man who always wore his Sunday best on a daily basis—was zip-tied to a basketball pole for striking the masked men who berated el residencial with controlled silence. Packs of ghosts, disappearing into each space and returning with bags filled with meow-meows and soft barks, black bags dragged behind each moving statue and tiny holes cut into each sack, brown eyes bright through the small creases.

“Don’t you dare take him,” Ma yelled out as she was restrained.

“Orders are followed, it is our responsibility to maintain sanitary conditions,” the figure said.

They had come to clean the mess we rolled ourselves in. They had come because the alcalde told them to. They came with false expectations; we never wanted to be clean.

Casero was the meanest cabrón that idled through the courts during mealtime. He would convince the oldies that he was cool because he sharpened his clothes to cut eyes, and if you looked too quickly at his gator shoes, you’d tear up blood from the glaring leather. Danny idolized Casero. He would tell me at night that he was “going places,” that Casero would bring hope to el barrio and that there wouldn’t be a need to push around el local anymore to make ends. That was Danny’s wish, but Ma wasn’t having it. So she went out and bought Chuchu from Casero. I believed it distracted everyone from the naked man in the room, the signs that were laminated in bronze lettering pointing up our nostrils and every fool boy from that shack. Running header: we were breadcrumbs. Birds were there to keep us from getting too fancy-eyed.

I stared from our balcony looking at Ma fence through Casero’s stock of dogs. He would sell them to drug thuggies at steep prices but kindly withdrew his haggle in order to satisfy a lonely viuda.

“Baby, I’ll sell you a pit for just 300. Pup that was bred by me especially for you from la madre patria. He’s about two months young. Your breed will like him,” he said through cigarette smoke coming from his bulbous lips.

“Ay no se. They’re a dangerous kind.”

“Only if you raise them to be. But I don’t think a fine fox like yourself would have to worry about that with your boys looking after it.”

She shied away from that comment and continued rummaging through the rusted cages. Casero probed her as she leaned, he’d flare his eyes every time she bent over, her brown dress lifting above her quads. With a keen drag of his cigarette, he walked up behind Ma and brushed her thighs with his pelvis. He patted her down and coiled his fingertips just under the edge of the dress.

“I’ll give you a discount if you’ll do me a favor.”

“What favor?” She turned to look at him. He blew a smoke cloud towards her while he cupped her chin. They stared for a moment, speaking through glares. I hadn’t thought, at that moment what that actually meant, but I figured there would be a good long prayer said to Jesuscristo—a bit of fuck, coño, and que rico to add to the flavor.

It had been a lonely time for Ma. She descended into the life of a common puta, picking up smoking like wildfire, later using her body to get little jobs here and there.

It had been a lonely time for Ma. She descended into the life of a common puta, picking up smoking like wildfire, later using her body to get little jobs here and there. She knew Casero before she married Pa. When he died, Casero skipped his way into Ma’s skirts and eased her grief with his fabled “anaconda lullaby.” See, I’m not sure if Danny was delusional about Casero, that maybe he’d take up Pa’s place. Maybe Danny really thought Casero was fat-lady luck flying in on that rainbow he needed to get out of here. He became so caught up in mimicking Casero’s speech, his strut, his rhythm. There were times it was just sad to see the two of them standing next to each other, an experienced cat teaching a hairball how to roll. Yet I knew Casero toyed with Danny, hanging over his head his late fucks with Ma. Almost telling him within earshot how he easily won over Ma’s affection while Danny had to be there picking up the pieces, not only the XL condom wrappers but even, at times, the baby battered blankets Ma was just too lazy to wash. It drained him.

We spent the days neglected. Skipping school and trolling the basketball court with college leftovers from the Caribbean University—a box of a building that hired any worker to teach remedial subjects to hopeful peeps. One by one, after the mirage of a better life faded, you’d see the boys drop off single-file. They’d tail their asses towards cockfighting, selling, soaking. Me and Danny hatched out of that shit.

“You think we’ll ever make it to the metro?” I asked Danny.

“Don’t matter much, there’s no difference here or there. Besides, I don’t think Ma would do good alone.”

“I don’t want to be here anymore than you do, Danny.”

“Grow up, Marcos.”

I wanted to follow him wherever he went. I’d grow up. Right there.

Danny and me attempted to progress on our schoolwork. Ma yelped for God fifteen minutes straight that night. The knocks of the wood banging up the concrete serenaded the apartment.

“There goes Ma praying.”

“Leave it.”

It wasn’t like we hadn’t grown accustomed to male wooers after Pa danced his way out of the picture, but something about Casero, that old bag, pissed me off. Though he manicured clean, shaved every hair on his body and even girls our age frolicked over his aging muscles, the wrinkles on his hands unmasked the years. Danny cooled his anger with his fantasies while I tapped my pencil on the table, syncing with the thuds of wood.

“I want him out of here,” I said.

“I said leave it, Ma’s got her own crap to deal with without your bitching.”

I kept attempting to focus on the police sirens that shuttled their way past the residencial. My eyes fixed on the mosquito that bit my leg. Or the tiny cockroaches that skated on the kitchen walls.

“I’m going in there, Danny,” I said getting up from the table.

“What are you on, Billy Jean? Easy with that moonwalk. You’re not doing that,” he said, grabbing my wrist and tying me back to the table.

“Listen, here’s a way to cope with it,” Danny got up and ran into our room. He returned with a VHS and handed it to me. “Take it to the bedroom, it’ll relax you.”

“What is it?”

We both stood there shaking the VHS between our hands.

“You’ll see, mijo. I’ll warn you though, lower the volume of the TV when it starts.”

I took the VHS and made my way into the bedroom. The room darkened as I entered and sat on the bed that overlooked the tiny TV. Static from the set cloaked the room with a gray light. In a sudden change from colorless to a sharp image of a familiar bed, I saw two images embracing each other. Their naked bodies stroking at each other’s genitals. An aging male figure with muscles that primed his sagging skin, while the woman, petite figure, and a handful of breasts began sixty-nining on the bed. The bedroom door was closed. Our bedroom door was closed. But I recognized that hair, black and coarse, easily malleable. Scars of a cesarean on the stomach.

My dick kept poking at me. Asking for attention. The echoes that resonated through the apartment continued to thump with wood against concrete. It was music to the throbbing in my jeans. Moans of “que rico, more papi, sí” harmonized with desire that soaked into the flashing images on the TV. An erotic film performing similar positions I’d grown used to seeing in flashy pornos Danny used to slip to me. I couldn’t control the movements of my hand strokes. I began to mime the repetitive thumps around me.

Casero just breezed by me and Danny on his way to the door. He tossed us a wink as he threw his shirt over his shoulder.

“Come by tomorrow and pick up the Dogo for the boys. Don’t be late nena because I have plans that night,” he said closing the door behind him.

Ma came up to us and sat down, her face dripping with sweat and her black hair sheared at the ends, a knot gesticulating at us her full commitment to our happiness. There wasn’t much said between us. The stares were enough. As she sat there panting, Danny scooted his way next to her and combed her hair, brushing it down to a more presentable shape. She just looked into his eyes and smiled. But I couldn’t.

I grew a liking to him from the very first barf on the new rug Ma had bought.

Chuchu wasn’t very big the day he tripped his way through the door. Ma had bought him an oversized black studded collar. He’d stumble around attempting to lift his round body, often gnawing at the leather strap left over. I grew a liking to him from the very first barf on the new rug Ma had bought. I hoped he was a rebel, he’d fit in perfectly with Danny and me. We wanted to be rebels, but for some reason, it was always me who put up the front. Danny would admire the thugs, the down hipsters, the pushers, but whenever he saw Ma weak, he’d come flailing to her aid.

“Do your work, Daniel. If you don’t graduate, you’ll have to join the army,” she said as she dried the plates in the kitchen while Danny passed each of them to her.

“Ma, I’m not joining those sellouts. I’ll pass and start up a business with Casero, he mentioned something about working with dogs.”

“Mira imbécil, are you stupid or something? Casero works with dogs for fighting, nothing else. You’re not getting caught up in that mess.”

“Ma, he’s got a plan, OK? Better than those fruity dreams Marcos keeps entertaining about universities,” he said this as he whistled an elongated note to me. I tugged on a yellow rope with Chuchu. I didn’t tell Danny about the envelope that came in the mail. I didn’t tell Ma about it either. I hoped to keep it a secret from them until we found out if Danny was going to graduate.

“Fruity dreams? Coño hijo get your head in line. Your brother’s been doing good in school, maybe he’ll get in at Arecibo.”

“Nah, he’s not thinking Arecibo. He’s stuck on Río Piedras,” Danny said, laughing. Ma smirked and let out a giggle upon hearing my idealistic wet dreams.

“Marcos, Río Piedras is a long shot. You’d be lucky if you made it into Arecibo.”

“Do you think you are better than us?” Danny said, flicking water at me from the sink. “Are we not good enough for Dr. Marcos and his air head?” I kept playing with Chuchu, ignoring the droplets that fell on my cheeks, wiping the ones that got irritable, the ones that Danny swam in, slapping my cheeks with his authoritative force. Pa smiling in Ma’s grin. Pa chuckling in Danny’s laugh.

I tugged Chuchu all the way to the bedroom and lay on the bed hoping for Danny to fail his year. He spent his time in a tally waltz with the girls he recorded. “Don’t you worry ‘bout a thing Marcos. When you start spicing up your dick with pussy juice, you’ll learn what it means to be a man.” Pa used to say the same thing. When we’d be sitting in the living room as a family, Pa would grab Ma’s thighs and high-tail his fingers up her skirt, and she’d always playfully attempt to slap them away, smiling that same smile she always shone through her teeth, as if telling us something through her dark eyes, asking for forgiveness.

I walked out of the apartment looking to air out my frustrations. I had taken the sealed envelope that I hid under the TV set from our bedroom. Wanting to escape from the gates that trapped me there, I pranced towards the entrance of the complex. Old lady loca sat on a bench. Her life soaking through her pores, letting in the bad sun that cooked her into a bronze statue. She was that eighty-year-old fossil that wore diapers to avoid the dripsies. She yelled out to anyone who crossed paths with her that the world was ending, we were all doomed, and nothing would save us. She fancied herself the prophet of Lomo and christened her subjects with her apocalyptic words. I frowned at her and frowned at the boys playing basketball. I saw the dogs walk around el residencial. The gates open. They could come and go as they pleased, but they remained, lying down, smelling their behinds, choosing to stay.

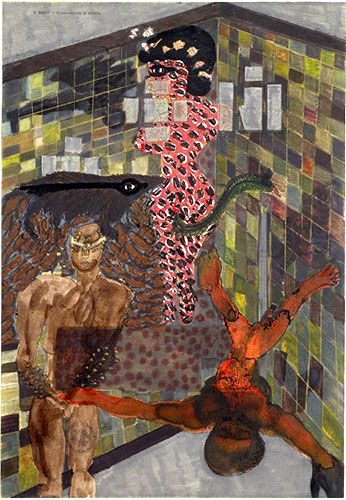

You and Luis headed the caravan that overtook el residencial Tito Lomo. You were given orders by the mayor to seize the pets harbored by the residents. The imminent threat of overpopulation and risky sanitary conditions was the only reason given. The residents, however, ignored their government handouts—buying and selling the lot of dogs amongst each other, creating gardens of manure and a smell deep in excrement. Most of the afternoon was trapped with an eastern sun, a haze of Sahara dust dancing on the thin clouds. You stood with a rifle in hand and a two-way radio saddled on your shoulder. You’d oversee the abductions from your lead car at the northern entrance of the complex, drying thick sweat that fell from your head on the patch of blue-collar. You grew impatient as dirt rose from the scramble in cages. Moans of cats being tossed into duffle bags; dogs stung with Tasers if they weren’t compliant while others noosed with a thick rod were dragged into the kennels at the back of each van. The noises barked into the open space of the central basketball court. With more noise grew your need to leave. You wanted to return to your house with the cool mountain breeze.

Luis stormed into apartment six. The door buckled from its hinges tearing itself away from the hollow wood lining. Marcos ran out of his bedroom and threw himself at Luis. His mother did the same. They performed a maddening play, screeching those sounds only a god would care to listen to. Their tears soothing, the only response.

After an hour of work, you straightened your stance and signaled your goons to group.

“Luis, finish up that last section. We’re heading out,” you said.

“We driving straight?” Luis responded as he threw a duffle bag full of cats into the back of his van. His shirt stained with damp yellow and patched with the sting of urine. Your arms marked with steady grazes and blood dried to black.

“Let’s hope so, no surprises on the way,” you said.

“None. But the vans are at full capacity. The weight is straining the wheels.”

“Then let’s get a move on.”

You investigated and collected animals from the apartments, dragging along Chuchu by his collar, pushing him into a kennel. The drive moved away from Barceloneta and neared Vega Baja. You led the caravan of four vans as they came upon the bridge. Your mind strayed into the line of water that could be seen. The tops of flowered trees cut across the valley and decorated the nestled mountains.

“Eh jefe, we have a problem. We need to pull over.”

“Shit, Luis. We need to make time. If that shelter closes, where do you think we are going to drop off the cargo?” You yelled into your shoulder.

“We need to stop,” Luis repeated, his breath muffled with every break. Tires slowed as the line of vans pulled to the emergency lane and came to abrupt stops. Luis was the first to open his door and walk towards your lead van. The other men in the two exterior vans slowly made their way out, slamming their doors as they tailed Luis.

“Luis, qué carajo pasó that we need to stop in the middle of a bridge?” You said, confronting him.

“Some of the dogs are dead in my van. There are some cats that also died. The smell tells it. We weren’t supposed to bring dead animals to the shelter,” Luis said.

“It’s going to cost a hell of a lot of money to euthanize this many maldito animals,” you reply. The highway was desolate. “And to bag the ones that died, disposing of them is going to create paperwork.”

“Boss said to take them straight on,” the passenger said to the Luis.

“I’m not driving all the way to San Juan with dead satos.”

Over the mountains, the houses began to light up under the darkening sky.

“We toss the dead over,” you said, signaling at the horizon. You grasped a duffle bag, opened the zipper and strewed the white, black, calico bodies out into the landscape.

“Oyé, mano, what are you doing? Are you insane?” Luis ran up and tugged the duffle bag of cats.

“The live ones, aim for the rift in between those trees,” you said as you mangled a living cat, its green eyes melting with the tight grip on its neck.

“The live ones, aim for the rift in between those trees,” you said as you mangled a living cat, its green eyes melting with the tight grip on its neck. “That creek spills into a sewage duct, that’ll drown them.”

“Drown them? They’ll be dead on impact,” the man said.

“The stubborn ones won’t.”

Luis overlooked the men digging into the vans as they tossed the animals—each of them, as if opening boxes of toys on Christmas morning. He did not participate in the fire sale. Yet you mockingly toed your way to the edge of the bridge, humming a tune by Tito Puente. You painted the sky with the animals in dreaded syncopation. At the peak of each tree, you were sure to use the ink of brown cats; they blended well in the green canvas. The heavier dogs would be better off mixing with water, so you used your hands like a pincel, and dashed the light with streaks of big bodies. Your drumsticks conducted the overture. You were the king of the timbal.

I returned to the apartment at night.

He tossed the plate at Ma as I tackled him.

“Malagradecido,” she said.

“Cool it, Danny. What’s gotten into you?” I said as I clawed him to the ground. Danny and me wrestled in a floor tango while Ma began the assembly line process of throwing out his clothes over the balcony. And in a momentary lapse there was immediate quiet. The tango had ended, the music had come to death. Danny shrugged his body away from mine and stood glaring at Ma.

“Take them with you maldita sea,” she yelled. Her hand grasping a plastic bag filled with steel jeringuillas. “I hope you meet him there.”

“I’m done with this shit. You’ve turned into nothing but a ghost. It’s no wonder you’re alone. Take a look around you, there’s nobody there. I’m gone,” he said, stomping his way towards the door. Ma’s imposition fell as quickly as it rose.

“Hijo, please.” Ma ran towards him letting the bag drop to the floor. “Don’t go. Get help but don’t go.”

“Get off me.”

Danny slammed the door behind him.

“Are you ever coming back home, Danny? Ma hasn’t left her bed in a week,” I said to him. We sat there for a while. Tata cooked us a meal in the kitchen.

“I’m thinking of staying around here, Marcos. It’s much cooler. Besides, Tata gives me food. And a beat-up car that I can use to drive about. I’ll start it up again around these parts.”

“What about school, then?”

“Ah, forget about that hole, mano. Life’s too short to be messing with books, look at what happened to Pa. He fed us that crap our whole lives and now look at him, staring up at us from the ground.”

“The government showed up in Lomo and took all the animals. Chuchu is gone,” I said in a dead tone. Danny just fiddled with the couch cushions and stretched out his hands in the air, letting out a sigh.

“Well mijo, what can you do?”

“What you mean what can you do? Show some compassion, dude. Shit’s getting slushy around there. Casero’s been living with us. He’s pushing hard now. And well, you know what that means for Ma.”

“What. She’s el carro público then. What’s the difference now? At least she’s getting paid some,” Danny said, standing up from the couch.

“See, Danny. That’s the type of crap that pisses people off.”

“Don’t start growing some big cojones now. You wouldn’t want to get slapped around,” he said. The kitchen pans clattered in the backdrop. “Listen Marcos, Chuchu’s gone, we can’t do nothing about it. He was a temporary thing in your life, like Casero, like any man that comes around that place. Ma’s been sleeping around since Pa kicked it. Look for a way out.”

“Like Casero, right? The mighty Savior. The guy you always pulled pants down, sucking that dick any chance you got.”

Danny stared at me. His fists clenched and shaking, ready to rumble. His eyes flaring like Casero’s had the day Ma transacted for Chuchu.

“It doesn’t give you a right to sell those tapes around the block. It doesn’t give us a right,” I said. My eyes growing heavy. “You know that shit killed him. You knew she would flip when she saw that bag. I told you not to get involved with Casero.”

“Fuck her man. Tata’s been more of a mother than that perra. Pa treated her exactly the way she was supposed to be treated,” he said.

I couldn’t understand his logic. Yet I didn’t blame the guy. Ma was lost in her grief.

I couldn’t understand his logic. Yet I didn’t blame the guy. Ma was lost in her grief. The train of guys making their stops into our space had us tired. She expected each one to be treated like her man. They weren’t. But I couldn’t help feeling we raped Ma. With everyone we let slip into the apartment. With everyone that sold her jumping breasts to our neighbors. And that weight we carried around our necks, telling the crowds of Lomo that we were that puta’s sons, we were the twins that sold their mother to gigolos, no different than any ordinary pimp. We failed. We watched her die over and over before our eyes, changing with every moan she cried, asking for our forgiveness. And we’d simply wash our hands in a bowl like Pilate.

“Whatever, man, I’m heading back,” I said.

“You thinking of walking? It’s getting late. You won’t make it till morning. I’ll drive you,” Danny said with a low voice, his anger subsiding.

“No, I’d rather walk.”

“Don’t be a puss. Let’s go,” he said kicking his legs at my shoes.

We walked out of the house. I yelled out to Tata that Danny was taking me home. At the hillsides of Vega Baja, the outskirts of the town that met the highway would glow in a green bubble as if in that small section of PR, the amapolas bloomed a full party. The trees desired heaven, trying to escape the blueness of a tropical sky, a perfection that reflected a plastic mess. Danny and me walked down the concrete walkway towards his rusted Corolla.

“That smell, you smell it, Marcos?” Danny said stopping at the car door.

“Smells fishy. But bad fishy, like old tuna,” I said.

“Like a bad pussy,” he said as he walked towards the edge of the road where a small creek trickled its way down its side. We followed the smell up the road that moved its way up a long line of imposing trees, towards the bridge of the highway.

“It smells like death, Danny,” I said covering my face.

“Look in here, mano.”

He positioned himself over an uncovered manhole. A smell of old cheese and humid eggs soaked into my nostrils. You could make out black nose tips in the muck of still water. Clusters of white hair sprinkled themselves atop the goo. And, like a cork that bobbed and weaved through a water landfill, icy eyes stared back at me, sinking me closer to their trance.

“Are those . . .?”

“Yup,” Danny said. He made to push me into the watery hole, but I dodged and shoved him away.

“Look over there,” I said pointing away from the road and into the shrubs of trees that flicked the belly of the highway.

We cleared the road and headed towards the bridge. A smell of sulfur pillowed our push past the thin trees. When we reached the corner pillars of the highway bridge, Danny elbowed me at the direction of the treetops. There, skewered into some of the bare branches were cats hung by their legs, drooping like falling kites in the sky, tangled astray on the leaves of those trees. At the footing, lime blanketed the roots. Danny and me walked closer to the lifeless bodies of decaying eyes, a studded collar, dogs half smiling with their tongues licking the white powder, and cats absently shunning away from our existence.