Image courtesy of the artist.

I first encountered Tim Youd’s performance art mid-performance, in front of Faulkner House Books in New Orleans’ French Quarter. Seated at a card table, pecking away on an Olivetti Studio 44, the Los Angeles–based performance artist was retyping, word for word, John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces, the fortieth entry in his 100 Novels Project. “I’m an unorthodox typist,” Youd said wryly. “I’d say that I’m probably as good as I’m going to get.” For the project, Youd was retyping, as the title suggests, 100 novels, each on a single, continuously rolled sheet of paper.

The criteria by which Youd selects the novels he’ll retype are relatively broad: They need to have been written in English (translations, Youd asserts, don’t capture the true flavor of a work or an author’s style) and on a typewriter (he’s amassed quite a collection since, whenever possible, he uses the same make and model that each author used).

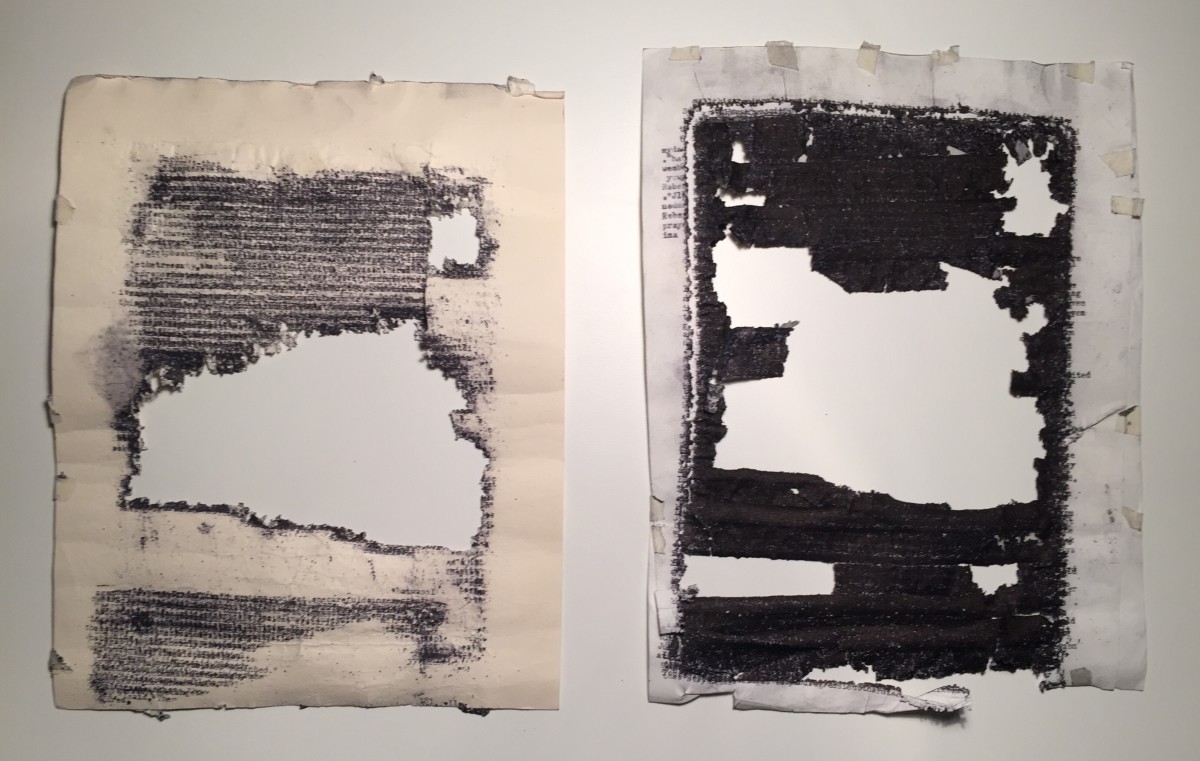

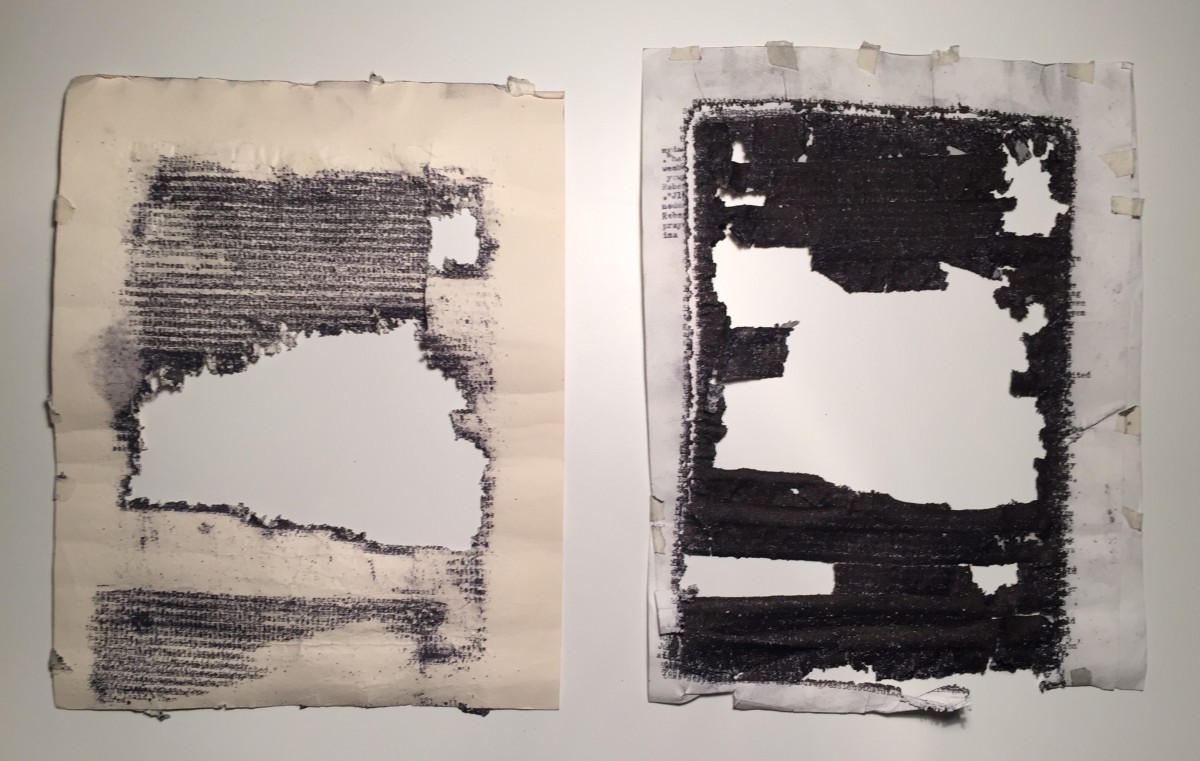

The result of each performance is a diptych that echoes a book’s visual formality—the sheet of worn, illegible, masking tape–patched typewriter paper and the backing sheet placed side by side and framed. For Youd, though, that result is secondary to the performance itself, which involves him setting up folding chair and card table, unpacking the typewriter, and sitting down to perform in locations specific to the novel he’s currently retyping.

The project has attracted the attention of museum curators and gallery owners, with the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego (MCASD), the Savannah College of Art and Design, and Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE), among others, hosting Youd for on-site performances, which he intersperses with site-specific performances. I spoke with Youd at the New Orleans Museum of Art, where he was retyping Ernest J. Gaines’ The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman, and where the exhibit “Tim Youd: 100 Novels” was on display.

—Heather L. Hughes for Guernica

Guernica: In addition to having been written in English and on a typewriter, what are your other criteria for selecting novels to perform?

Tim Youd: Well, I have to like it; I have to feel it’s something I want to spend more time with. Because some of them, in the instance of Confederacy for example, that was pretty close to 100 hours of typing in a very concentrated sixteen or seventeen days out of eighteen days. The exercise for me is to really try to come to terms with that novel over the course of the performance, so I want to make sure it’s something I feel is worth exploring.

Guernica: Has your work always been performance art- and word-based?

Tim Youd: I’ve never done performance art before this. For quite a while, my original art has had to do with texts of literature, but it was really all about how texts and literature manifest themselves visually. That was a gateway into this project in the sense that I was trying to get at that formal rectangle within a rectangle. And then the performance just kind of happened, accidentally and organically, and that’s been great for me. Because I’m not always anxious to get up in front of people; I mean, that’s not my thing. So it’s forced me out of my comfort zone.

The diptych was what came first; that came before the performance. I was producing this diptych, so I backed into the performance when I realized that it could be about the reading and it could be about this devotion to the text as much as it is about the production of a physical piece of art.

Guernica: So far, most of the novels you’ve retyped are by male authors. When you compiled the list of novels you might want to retype did you consider gender?

Tim Youd: For starters, I didn’t know I was going to type 100, so the first novels I retyped were Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint, a couple of [Charles] Bukowski novels. They’re all kind of aggressively male writers; I probably have read more in that direction than in anything else. It may be more that I had done visual work around Bukowski and Roth and Henry Miller and so they were on my mind. Maybe that’s what I happened to be reading around the time this thing started.

I don’t want to wind up picking a novel just because it’s by a woman, because that wouldn’t be very honest.

And then the Miami thing happened [Youd retyped Elmore Leonard’s Get Shorty at the 2013 Aqua Art Miami, a satellite fair to Art Miami]. And that led right to the MCASD show, which was all seven Philip Marlowe novels, so all of a sudden I have twenty and I haven’t typed any [by] women. And by that point, I know I’m retyping 100. So, the ratio is out of whack, and by the end I will have retyped twenty or twenty-five novels by women. I don’t want to wind up picking a novel just because it’s by a woman, because that wouldn’t be very honest. And the reality is, particularly for the typewriter generation, it’s an odd change that kind of occurred, because if you think back to Victorian times, women [authors] are dominant or certainly creating works that are influential. But at some point, in the early part of the twentieth century, it becomes very male dominated in terms of what got published.

It was fascinating when I was in England. I retyped To the Lighthouse in Cornwall, on Godrevy Island in St. Ives Bay. [Virginia] Woolf used to summer there with her family when she was young. And even though the novel is set on the Isle of Skye in Scotland, it was really about the Godrevy lighthouse. So I sat out on this bluff and it was wonderful, really beautiful. And then I retyped Orlando at the country home that she shared with Leonard, her husband, in East Sussex, right where the river Ouse runs, which is where she killed herself.

What was fascinating to me was that the National Trust manages the Virginia Woolf property and it also manages Rudyard Kipling’s property, which is in that same area. Kipling became a very, very wealthy man, and Bateman’s is like a country mansion or a country estate. And the sense that I got from talking with people is that that property gets far more attention than Virginia Woolf’s; it’s a bigger draw for tourists. And I was trying to make sense of that. I mean, I love Rudyard Kipling’s children’s stories, but his mature work? He’s a jingoist and he’s a racist. He was a man of his time; I’m not saying that he was abnormally cruel or out of step with his time. And then you have Virginia Woolf, who’s for all time and one of the greatest novelists ever. I mean, if Virginia Woolf is even today somehow—not literarily, but in terms of a literary pilgrimage—if she’s rated below Rudyard Kipling, then you’re up against something, right? I mean, something is kind of messed up.

Guernica: You’ve mentioned before that the retyping is a devotional act for you. When you retyped Fear and Loathing, and you weren’t aware at the time that you were going to do 100 novels, was it still a devotional act for you, or was it more of an unusual piece of performance art?

What’s more of a staple of modernism and post-modernism than just a rectangle inside of a rectangle?

Tim Youd: It was devotional in the sense that I was really reading the novel. I wasn’t just mechanically typing to create the diptych, to create the relic. Although the idea was, “Okay, here’s what I see when I look at a book,” [which is] where the whole impetus for the project comes from. When you’re looking at a page of a book, you’re looking at this rectangle of black text inside the rectangle of the white page, and again on the next page, right? So you’re looking at this very formal thing, right? What’s more of a staple of modernism and post-modernism than just a rectangle inside of a rectangle? I was intentionally trying to create that artifact, but I was definitely closely reading while I was doing it. And if it had not been satisfying in terms of the time spent, not in terms of the output but in terms of the time spent—in other words, if I wasn’t getting something out of the reading, I can’t imagine that I would have said, “Okay, I’m doing 100 of these.” As I’ve gotten further into it, I’ve seen even more clearly that not only is it an act of devotion toward that specific novel that I’m retyping, it’s also this opportunity to not just be a good reader in the moment but to become a better reader over time, which makes the journey exciting for me. I’m going to be better at something that I love to do; in fact, it’s probably what I love to do most.

Guernica: Do you find that the conversations you have when you’re performing at a site-specific location are different from those in a more “curated” setting, like an art gallery or a museum?

Tim Youd: It’s definitely different. Certainly Pirates Alley in the French Quarter [where Youd retyped part of Confederacy] was a singular location in terms of the characters that I met. And there were a lot of people interested in engaging with me. That’s not always the case when I’m typing outside of an art context, but I think the particular nature of the Quarter and that you have others on the street performing or engaging with people made the idea of approaching me fit in with the mind-set of the place. And a few drinks doesn’t hurt either. But sometimes I’ve been in places where people are a little more reluctant. Am I just an unstable person sitting and typing? What am I doing? Am I a “give me a dollar and I’ll write you a poem” guy?

Guernica: What has the reaction been like?

Tim Youd: I had a guy today—he was a psychologist and he was pressing on why am I doing it, and by typing over and over the author’s words, isn’t it an affront to the author? I’ve heard that a few times before, but 99.9 percent of the time if someone’s engaging with me, they’re not tripping over that.

I understand intellectually what he was trying to say. But for me it’s another celebration of the work, and as a visual artist it would be kind of lame to just type out something. I mean, it’s going to be full of typos and do you really want my complete retyping of A Confederacy of Dunces so you can read it? You’re not going to read it; you’re going to go buy the book so you can read it.

Guernica: How many of the authors whose works you’ve retyped so far are still alive?

Tim Youd: Besides Roth, Tom Wolfe. In May and June, I’m going to retype two novels by John Rechy: City of Night is an important novel sociologically, and it’s a great novel in terms of literature. It’s a little over fifty-years-old now, and it’s the story of [Rechy] as a male hustler. I actually got to meet him. He still has the typewriter that he typed City of Night on.

The other novel that he wrote on the same typewriter was Numbers. And again, it’s a thinly veiled autobiography telling the story of his attempt to… how many men could he have sex with in Griffith Park in twenty-four hours?

LACE sits up on Hollywood Boulevard, where a lot of hustling was taking place, and although I think the city has pushed a lot of the prostitution off the Boulevard, there’s still an edge to it, certainly at night. For City of Night, part of the time I’m going to sit out on Hollywood Boulevard. I’m going to retype the thing in the middle of the night basically. So it’ll be interesting.