Blackness meant many things to the American photographer Louis Draper. It was the empty social construct whose brutal effects he grew up with in pre-Civil Rights Virginia. It was the proud and defiant identity he fashioned as a response. And it was an aesthetic: a conscious negotiation of light and shadow, black and white contrast, and gray tones. His work, which is currently on display at Manhattan’s Steven Kasher Gallery, is fascinating because of the ways in which these disparate ideas of blackness inform and finally merge together. For consolidated, they result in a very rare thing: beautiful political art.

Louis Draper was born in 1935 into an African American family that his sister Nell would later describe as being “poor in money, but rich in everything else.” He graduated from the then-segregated Virginia State College with a degree in history before deciding—the catalyst was a chance encounter with Edward Steichen’s Family of Man exhibition—to move to New York City in 1957 and make it as a photographer at a time when the only known black photographers in America were Roy DeCarava and Gordon Parks. Though his father was an avid amateur, Draper had never seriously taken pictures before. His early classes in New York, with humanist pioneers Harold Feinstein and W. Eugene Smith, can thus be considered his formative introduction to the medium. Acknowledging their influence, Draper would later claim that, “I am a photographer rooted in the humanistic tradition. My influence [has] has been W. Eugene Smith.”

What Draper had to do was develop a new a visual language: one that portrayed his subject’s humanity, while also calling attention to how it was being denied.

This, I think, is only half the story.

Draper is certainly a humanist in his head-on depiction of social realities. But there is also an expressionistic, and indeed symbolist strain that runs through his work. His subject matter—black America—called for it. Draper began photographing black people in the late 1950s, a time when their humanity was still denied by the American government. The idea of ‘humanism,’ then, took on a dark irrelevance in the context of his work. What Draper had to do was develop a new visual language: one that portrayed his subject’s humanity, while also calling attention to how it was being denied. In other words, he had to figure out how to photograph “blackness.” Recognizing this, he once said that:

Starting in 1958, Draper embarked on career-long exploration of New York (particularly Harlem’s) streets. What he saw there facilitated the translation he sought to achieve.

Draper’s early work depicted ordinary black people with great sympathy. The girl in the untitled photograph below, for example, is caught with a mischievously pensive expression that one can’t help but feel curious about. Draper arranged the light so that her face is the most luminous surface of the photograph. Finally, and you will have to visit the gallery to ascertain this, the shot looks even better in Draper’s self-made vintage print than it does here. As another black photographer, Shawn Walker, would remark decades later, Draper’s “photographs were printed so well, they were three-dimensional. I’d never seen such beautiful photographs of ordinary black people.”

It’s important to note Walker’s surprise. Enough white photographers at that time took a perverse glee in parading black people in squalid surroundings or in distorting their facial features. Draper’s photographs were radical simply because they presented black people in a positive light.

But Untitled also carries a more explicit political message. Draper has framed his shot so that a black pharaoh painted on the wall neatly parallels the girl’s posture. As the scholar Iris Schmeisser notes, this is a direct allusion to the “’stolen legacy debate’ of Afrocentric discourse” as well as a comment on the “significance of a cultural anchor for black identity formation.” In other words, Draper has presented his subject against the backdrop of her stolen history.

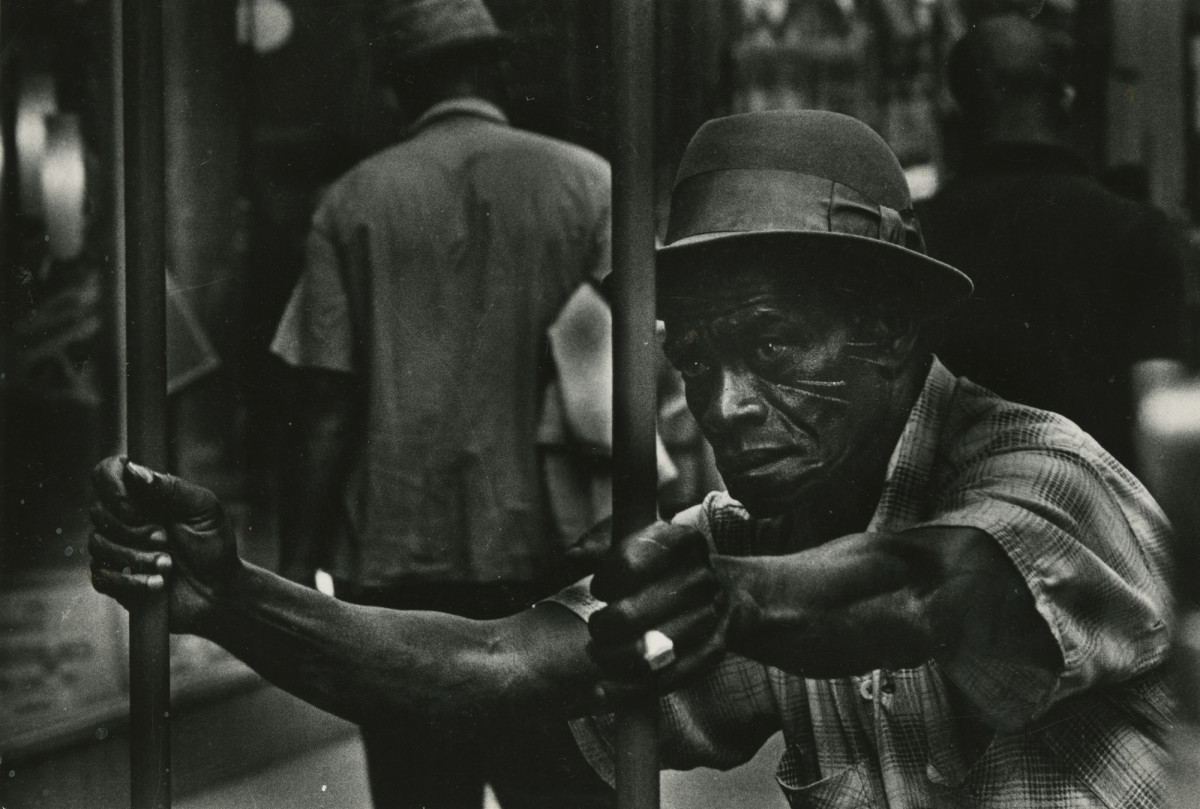

And his symbolism only gets darker and far more pronounced in the following photograph of a man resting on iron bars.

Wash out the background here and you’d be convinced that the man is in a prison cell. In truth, he’s really just standing on a street. The question, then—and I needn’t highlight its relevance to present debates about mass incarceration—is whether there’s much difference between these two places for him.

This juxtaposition—between the marginalization of African Americans, and their defiant black beauty and resistance—is in itself a powerful aesthetic.

Such symbolism (the pharaoh, the prison bars) allowed Draper to portray the social of African Americans. What’s important is that he didn’t allow us to equate his subjects with their situation, but instead drew attention to their inviolable will to live. Indeed the girl in the previous photograph looks nothing but graceful and lively, despite the ominous symbolism of her surroundings. The man here, likewise, is presented with an austere, sculpted handsomeness, as well a rugged endurance. This juxtaposition—between the marginalization of African Americans, and their defiant black beauty and resistance—is in itself a powerful aesthetic. But Draper would soon add to it the concept of tonal or visual blackness. And that final technical innovation was what unleashed his true artistic vision.

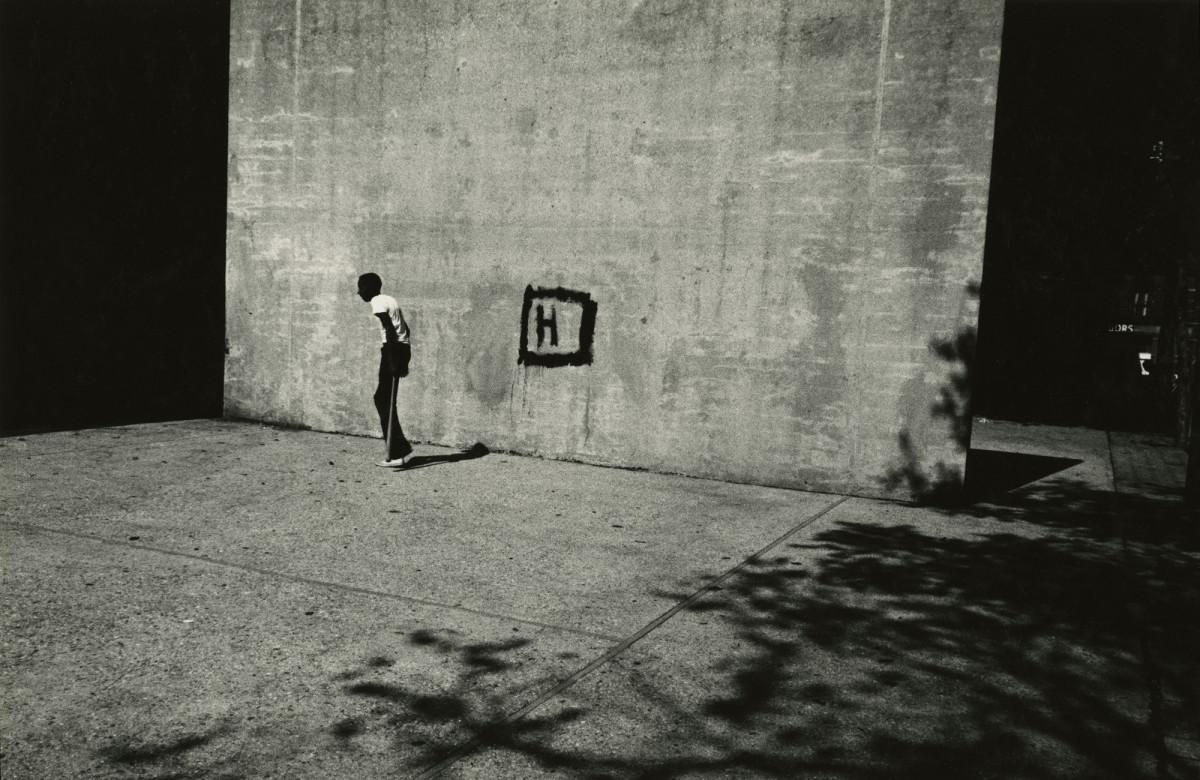

In Boy and H, one of the many memorable photographs he took of children in Harlem, Draper captures a skinny boy walking across a deserted pavement with his stoopball bat in the afternoon. As with previous photographs, Draper is using a city wall as backdrop for his subject. Interestingly, he has underexposed his photograph so that the boy, and almost everything on either side of the wall, appears pitch black. Whiteness is only present in the photograph’s central panel. The boy, then, is walking across the white zone and into the blackness at the edge of the frame.

But that doesn’t mean that he’s making some ominous metaphorical journey. In fact I would argue that Draper has subverted our social conceptions of blackness by focusing on the uncorrupted aesthetic aspects of color rather than a human story. Consider, for instance, how the boy’s facial features have been more or less washed out. And consider the pleasing formal tension of its black and white pattern. Indeed what strikes us first about Boy is its robust tonal effect.

Having said all that, I will admit that Draper is also playfully hinting at a metaphorical transgression of spaces (remember this was shot when America was still segregated). And such a transgressive gesture exists in the next (and perhaps Draper’s best) photograph.

Two children—a girl smiling delightfully in the foreground, and a boy running doggedly in the back—are captured crossing a street. The human drama of the scene here owes much to Cartier Bresson (another great chronicler of children) and his “decisive moment.” But the cunning tonal arrangement, as well as the spatial metaphor, is all Draper’s. As with Boy and H, he has placed a band of white (this time a zebra crossing) down the middle of his photograph, and is showing black children playfully transgressing that (color) line.

What’s different this time is that the children have themselves not been reduced to aesthetic objects. Instead Draper has captured their freedom and vitality with utmost clarity. The photograph thus operates as a double liberation. By depicting them as vital agents, Draper is liberating these characters from the negative stereotypes of the time. And through his clever formal arrangement, he allows them to metaphorically transcend the more intractable problems of spatial segregation.

Draper would have been an important political figure just on the basis of his photography. But he also supplemented his artistic work with a more direct form of political engagement: the formation of a black photo-collective.

Early in his career, Draper realized that America’s photographic community was “largely hostile and at best indifferent” to the interests of black photographers. DeCarava and Parks aside, black photographers were almost never given magazine work or displayed at galleries. This is the sort of injustice that can pit minority artists against one another. Instead, it led Draper and fourteen other young black New York photographers to form “Kamoinge Workshop,” America’s first black photo-collective.

In Kikuyu, Kamoinge translates to “a group of people working together,” and the workshop was intended to be space where black photographers could support and critique each other’s work. “We saw ourselves as a group who were trying to nurture each other,” Draper would later write, “We had no outlets. The magazines wouldn’t support our work. So we wanted to encourage each other…to give each other feedback. We tried to be a force, especially for younger people.” Kamoinge was founded in 1963, and over fifty years on, it’s still an active organization, making it America’s oldest black photo-collective (a retrospective of their work, titled “Timeless,” is currently on display at Wilmer Jennings gallery).

. “Why,” Adger Cowans, a co-founder of the collective, recalls asking at their first meeting, “are all the photographs that people take of us so ugly?”

Kamionge’s agenda of supporting black-artists went hand-in-hand with its commitment to positively depicting the black experience. Enough white American photographers, at the time, were incredibly derisive and condescending towards their black subjects. “Why,” Adger Cowans, a co-founder of the collective, recalls asking at their first meeting, “are all the photographs that people take of us so ugly?” It was a question, or rather a paradox, that haunted and spurred everyone at Kamionge, no one more so than Draper. Though he would go on to photograph celebrities like Michael Jackson and Miles Davis, and political activists like Fannie Lou Hammer and Malcolm X, he remained most interested and committed, throughout his career, to depicting ordinary black people with beauty and dignity.

In this way Draper’s career can be read as a response to the claim that Langston Hughes’s made in his 1926 essay “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” that a black artist struggles to “interpret the beauty of his own people” because “he is never taught to see that beauty.” Not only did Draper see this beauty, he managed – to our great benefit – to capture it for posterity.