David Bowie is dead.

The sadness of that statement is with me as I type, and it’s been with me since I woke up on January 11th. For days, I couldn’t stop thinking about him, as though his life and now his death were a pair of beautiful, painful baubles I couldn’t stop inspecting. I tried the words in different patterns: “Bowie’s dead.” “Bowie: dead.” “Bowie. Is. Dead.” I wasted hours reading all the articles about him in my newsfeed and poring through Google image searches to find the photos that matched my ideas about who he was. It didn’t make any sense. How could a personage of that magnitude do something as ordinary and time-bound as dying? How was it possible that nobody had known he was so sick? And who was I to give a shit, really? He wasn’t my dad, he wasn’t my husband. But when I stepped outside to walk the dog the air felt different, as if it had lost a smell I had always taken for granted. I know that sounds melodramatic—and it is—but it’s also true. I thought about living on the same island as so many celebrities and why none of them resonated with me as much as the man who had just died.

In order to figure out why, I spoke with Simon Critchley, Hans Jonas Professor of Philosophy at the New School and moderator of The Stone, a New York Times blog which features writing from contemporary philosophers “on issues both timely and timeless.” He’s also the author of many books including Bowie, a collection of lyrical mini-essays about the eponymous icon and the different thematic and conceptual valences of his music.

As we spoke over beers in Brooklyn last week, the night took on a magical sheen. Our little booth was a bulwark against the world where business moved as usual. All around us people came in and out of the bar, chatting, laughing, taking off and putting on coats, hats and scarves. Being friends. Having a good time. As though one of the biggest stars of the modern era hadn’t just died, or as though they didn’t care. Near-vintage pop hits reverberated in the background—Hall and Oates, Sade, Tom Petty, Marvin Gaye, etc.—but no David Bowie. Yet it was as if by talking about him for so long Simon and I recaptured a bit of the dark sparkle he had embodied and transmitted to his fans and the culture at large.

-Ari Braverman for Guernica

Guernica: Why do you think David Bowie’s music has maintained its appeal for so long—and do you think it will last now that he’s gone?

Simon Critchley: It will. No doubt at all. On some level when you’re talking about music you have to be vulgar and be able to say, “This is just really good.” A lot of people did what Bowie did, a very few of them before Bowie (Tony Newley, Syd Barrett) the rest of them after, but no one for me came anywhere close to being as good. There’s something about the craft and quality of his work that just makes it better. The technical proficiency of what he did with his voice, given his vocal range (he didn’t think his voice was good enough, back in the day), is often overlooked, the amount of time he spent in the studio just trying to get the right effect. Robert Fripp shares this story about watching Bowie in the studio, trying for hours to get his voice to match the emotion in the music. That’s complete artifice, complete inauthenticity, and yet he’s able to hit those feelings in a way no one else could. And what you feel when you hear that is something simply strong, powerfully true. That’s where he achieved his magic. In the songs. Without it Bowie could just have been a really clever mobilization of a Warholian aesthetic. The stage performances, the shows, the costumes, the interviews he gave—in a sense we could say they’re really, really important but they’re not the thing for me. For me, it’s all about the songs. On almost all of his recorded albums he was able to do something which no one else was able to do. It resounds on the level of your being. It shakes you up. It makes me tingle just thinking about it. Bowie was a fucking genius and the most important artist in any domain in the last half century. Period, as you say here in the US.

The connective line through all of it is him, it’s David Jones, who couldn’t really be a pop star and so became something else, something much more intelligent.

Bowie’s star quality is intrinsically linked to his exposure, his weakness. He wasn’t Mick Jagger or Iggy Pop, who are pure phallus. He wanted to be like that but he knew he wasn’t, hence the mutability. These were pretenses he put on and took off, which isn’t unlike what his fans do. What so-called “regular people” do. The connective line through all of it is him, it’s David Jones, who couldn’t really be a pop star and so became something else, something much more intelligent.

Guernica: Is that why so many people feel so bereft after his death?

Simon Critchley: The address of Bowie’s work has always been incredibly intimate and visceral. When “Starman” was performed on Top of the Pops on July 6, 1972 there’s this bit where he sings “I had to phone someone so I picked on you” and points right at the camera. In that moment he was picking you out, from the audience. The call was clear. You felt like he was allowing you to feel a whole range of things you didn’t even know existed. On one hand he mobilizes this self-conscious aesthetic of fiction and metafiction and irony in which everything is television and everything is a film set with this dystopian backdrop. It’s the most self-referential, most reflexive music we have, but it’s his inauthenticity that enabled this intimacy to happen. His music isn’t cold; it’s throbbing with desire. With warmth and love. It offers his listeners the possibility to synthesize themselves and to become something else, offers people new ways of being the kinds of people they want to be.

There’s an extraordinary vulnerability about Bowie’s work. He sang about isolation, despair, depression, and he sang about yearning for love, for actual human connection. Often those feelings are side by side in the same song. “Heroes” is like that. You’ve got the title track from Sound and Vision which is about depression and isolation and then the next track is “Be My Wife,” which is a demand for someone to please to come be with him. Bowie’s music is not a celebration of exile, it’s a yearning for connection—that’s what he’s left us.

Guernica: I told someone that I had literally never considered the fact that he might die. It was like he had almost become a natural force.

Simon Critchley: Yeah, it won’t happen again. I can’t think of anybody remotely comparable. The music industry has changed, what it means to be famous has changed. Now you can be famous by virtue of being famous, which usually means by virtue of your family position and the entitlements you have. You can be a Kardashian or a Miley Cyrus. Bowie’s father worked for St. Barnardo’s Children’s Home, his mother was a waitress. They were just ordinary working people. Bowie knew that making it as a star meant you could be really rich and that was enormously appealing. And he made it happen. He was constantly working, constantly listening, constantly reading, constantly soaking things up. There was an absolutely stubborn single mindedness to him as an artist. He just did what he wanted and pushed it through. He was also a lot cleverer than the people around him. He kept moving. But it is the sheer intelligence of Bowie that is breathtaking. As he said, he wasn’t a rock star, he was a medium for a new range of artistic creation.

Ultimately, he represents a fifty-year slice of pop cultural history—and therefore cultural history.

Guernica: Often it seems like artists find the thing they’re good at and stick to that.

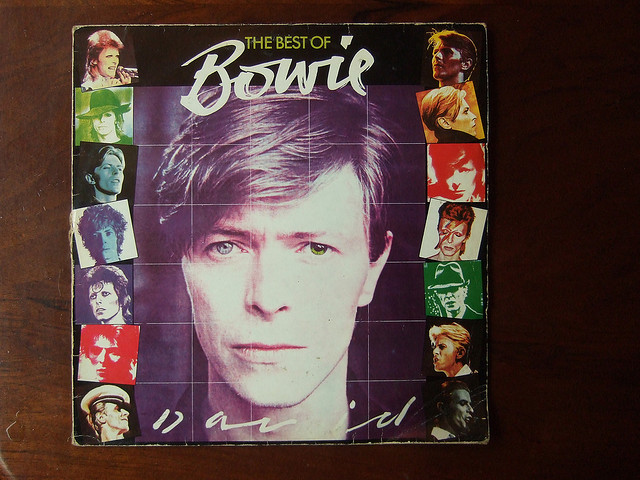

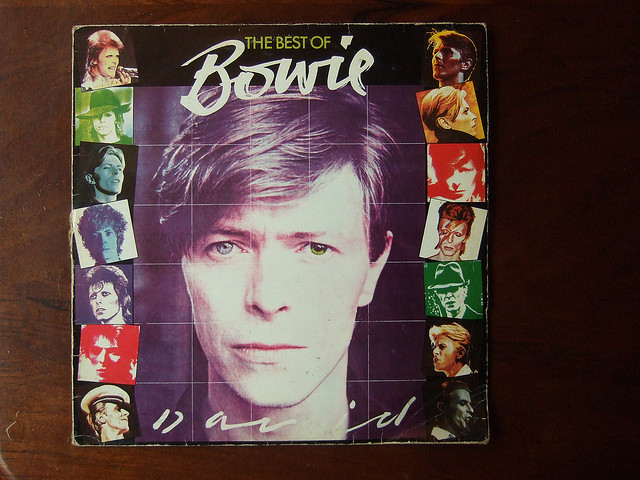

Simon Critchley: And they do it for maybe three albums if they’re really lucky. And that can be great—take the Velvet Underground for instance. But it’s all they do and then they’re frozen in that moment. Bowie knew when to stop and that’s remarkable. He was nimble. Look at the period from 1971 to 1980, which for me is the great period. Hunky Dory is a perfect singer-songwriter album. It’s intelligent, clever, it was very well-received, critically speaking. But it didn’t sell. Immediately after that he does Ziggy Stardust and The Spiders from Mars. It takes about three weeks to record and then he makes it big in the UK. Having become a huge star he does Aladdin Sane, where rock begins to unravel. Then comes Diamond Dogs where rock disintegrates. After that, with Young Americans, he shifts from the most dystopian, Burroughs-esque butt-end of glam rock into his version of R&B, what he called “plastic soul.” But he was already anticipating his next change. He was listening to a lot of German experimental music in that period, and in Station to Station you can feel the aesthetic begin to shift and open towards what he would then do in Low and Heroes, which were commercial disasters. You can see Bowie twisting these forms that have made him hugely successful, all the way through to Scary Monsters, by which time he had become the most influential figure in British popular music. For an artist to go through that period of production its amazing. Ultimately, he represents a fifty-year slice of pop cultural history—and therefore cultural history.

Guernica: And now, with his death, he’s become a part of that history. How do you feel about him dying, these couple of days out?

Simon Critchley: My book on Bowie was a fan’s book, a pledge of love for David Bowie. One reason that I came to New York—and I know this sounds creepy but it’s true—was that I could be in the same city as David Bowie. Seriously. Reality came out shortly before I left England and I thought, “Yeah, fuck! I’m gonna be in New York and Bowie’s in New York. Maybe I’ll meet him! Maybe we’ll have a natter and it’ll be nice.” It’s ridiculous! The last few years, particularly when The Next Day came out in 2013, it was his survival that became hugely important to me. He endured. That was the way I’d set it up in my mind, so I’m feeling…completely bereft in some way. I feel like I’ve lost the man I most admired.

Ultimately his death is something I’m still trying to figure out. It’s really peculiar listening to Blackstar. I was playing it to everybody on the Saturday and Sunday and went to bed and Monday morning was awoken by these text messages from England saying “Bowie’s dead.” In a certain sense listening to the album now that he’s died is a very different experience. He released it and died two days later. And yet it’s a Bowie album in continuity with other Bowie albums and so we must consider it in that light, too. All of his work has been very largely about death, from Space Oddity onwards, so it’s not as if there’s a shift in theme. He was fascinated with those creatures that somehow had a foot in the world of the living and the world of the dead. Bowie was a kind of ghost figure. Major Tom is a ghost figure. “Lazarus” is a prime example of all that, so it didn’t necessarily stand out when people first heard the album. But obviously Bowie’s actual death has changed that. That being said, I find the video for “Lazarus” almost too much to bear. I can’t look at him dying.

Guernica: I know you think of Bowie’s death-haunted, dystopian project as an ultimately utopian vision. Will you explain that a little more?

Simon Critchley: The context for his music is post-revolution, as in “The sexual revolution happened and it’s shit. It’s just the same reactionary stuff, only with more hair.” Bowie left England for New York in 1974 and he never lived in England again, at least not permanently. What replaced it was America. If he wants to be “David Bowie” it’s where he’s got to be. He was compelled by America. And yet there was something terrifying about America for him. In Diamond Dogs America is dystopia, the vision of hell, that commodified, degraded, flat, brutal, barbaric hell. A kind of hyperreality. Bowie’s utopianism is a really radical position. It communicates the need for constant de-creation, this persistent emphasis on nothing in the name of some other register of experience. There’s even a spirituality in Bowie which is completely at odds with any kind of organized religion or any faith in an existent God. And all of it communicates that this whole shitshow called civilization has gotta go. In its absence, Bowie, his personae, allow us to imagine different ways of being, different gatherings of people. For me, that’s politics. There could be a bunch of people in a back garden somewhere, or a bunch of people in a bar singing karaoke badly, and for those moments we can be us in some different way, maybe just for a day. Bowie’s music is one of the things that allows that to happen. I think that’s about the best that human beings can manage. Call me a little pessimistic but I think that’s quite a lot.

In Bowie I hear a voice crying in the wilderness. Really. He is this plaintive voice which feels radically alone, commanded by a black star.

Guernica: You’re describing a constant negation which at the same time demands, yearns for that connection you mentioned earlier.

Simon Critchley: In Bowie I hear a voice crying in the wilderness. Really. He is this plaintive voice which feels radically alone, commanded by a black star. That’s what’s coming for all of us, and that’s the sign that hovers over all of Bowie’s work. It’s only when that black sun of melancholy and depression is exerting its force most strongly that the counter movement could be felt. That is the apparent paradox of his work. This is also the riddle of great comedy: that it’s always about the dark side of the moon. It always portrays an experience of the most incalculable pain, and it’s only when you’re in the company of someone who’s frequented that pain, who is open to it, that something really resonant can take place. His music comes out of that feeling, out of a very basic mood which asks “Are there people who feel at home in the world?” It always seems like there are. Those people at the bar seem to be having nice time, but I’m sure to them it seems like we’re having a nice time, like we’re at home in the world, talking to each other over a beer. But I never felt at home in my skin, so when Bowie spoke to me I had that sense of connection with someone who understood how remote someone could from this world and how anxious this world makes you feel. And eventually, of course, you discover that everybody else feels like that too. Bowie is legion.