By Franco Galdini

The black SUV screeched to a stop. Through the smoked glass windows, I could only catch a glimpse of a silhouette in the inside. All of a sudden, the door in the back swang open. The voice on the other side of the phone ordered me to hop in. I hesitated for a second and then yielded. Manas met me with a smile punctuated by golden teeth. One sturdy bodyguard sat between us; another was in the front seat next to the driver.

A former mercenary with the Russia-backed rebel army in eastern Ukraine, Manas returned to his native Kyrgyzstan after feeling betrayed by Russian propaganda. “We were told that fascists were rearing their ugly heads in Ukraine,” he said once we reached a safe house, “but I haven’t seen any during my time fighting there.”

Upon his homecoming in March 2015, Manas received a hero’s welcome in Kyrgyzstan, a small former Soviet republic in Central Asia that has increasingly gravitated back into Russia’s orbit in recent years. People would shake his hand in the streets of Bishkek, the country’s capital, which he proudly walked wearing a uniform with the insignia of the Luhansk People’s Republic (LNR), one of the self-styled independent entities carved out of the eastern Ukrainian region known as Donbass (the other is the Donetsk People’s Republic, or DNR).

He was even invited to the White House, the seat of Parliament in Bishkek, to meet with prominent politicians. He remembers how “at that point, I could walk openly, with my head held high, as I’d fought for Russia. At the White House, everyone was greeting me; the atmosphere was very friendly, warm even.” Two members of Kyrgyz President Almazbek Atambayev’s own Social Democratic Party suggested that he appear on local media “to support our cause,” basically toeing Russia’s line that this was an existential battle against fascism.

Until June 2014, Kyrgyzstan was the only country in the world to play host simultaneously to a US and a Russian airbase”

That day, he noticed a group of people demonstrating outside Parliament against Russia’s meddling in Ukraine. Among them was an old friend of his. An altercation broke out between the two, as the LNR uniform betrayed which side Manas had fought on. His friend begged him to “clear your conscience and tell the truth,” as the situation in Ukraine wasn’t that removed from Kyrgyzstan’s: “pro-Russian forces are making a comeback in our country, too.”

A few days later, Manas entered the studios of Radio Free Europe (RFE) in Bishkek where he gave an exclusive interview, exposing the extent of Russia’s involvement in the war in Ukraine on the side of the rebel forces. The interview was a hit and turned him into a wanted man overnight. “That’s when I realized how pro-Russia we are. I told people the truth and their attitude towards me changed completely.”

A marked man, he took refuge in his native town of Talas, in the country’s northwest, where he lived in a safe house among trusted friends with a security detail. This was spring 2015. He has been on the run ever since.

Russia’s long shadow

Explanations vary widely as to why Manas decided to go public about his experience in Ukraine. For one, he claims that true patriotism moved him to join the fight in the first place, as his grandfather had served in the Red Army against the Nazis during the Second World War. The same patriotism now obliged him to reveal Russia’s duplicity.

A local opposition politician who met him after his return from the front mentions a more prosaic reason: money. Russia had failed to pay Manas—and many other mercenaries—for his last three months of service, so he wanted to square accounts with his former master (Manas alleges instead that he lost 4,500 USD in unpaid salaries as retaliation for his RFE interview).

Be it as it may, his public declarations catapulted him into a game far greater than himself, where his personal story became embroiled in geopolitical rivalries and the regional repercussions of the war in Ukraine.

Until June 2014, Kyrgyzstan was the only country in the world to play host simultaneously to a US and a Russian airbase. Located at Manas civilian airport in Bishkek, the Manas Transit Center turned into a key hub to airlift NATO and coalition servicemen and women, as well as supplies, in and out of Afghanistan in the context of the war on terror. Russia, which had acquiesced to the opening of the base following the September 11 attacks, viewed with suspicion a US military presence in what it regards as its post-Soviet sphere of influence.

Observers believe that a combination of Russian pressure and economic incentives won over the Kyrgyz side to ease the US out of the country. While the Manas Transit Center shut down in summer 2014, Russia renewed its lease of Kant airbase, some twenty kilometers east of Bishkek, for another fifteen years in 2012 and has since increased its military imprint in the small Central Asian republic. Kyrgyzstan has moved even closer to the Russian fold this past summer by joining the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union (EEU).

Following the RFE interview, Manas alleges to have met with a First Secretary and Section Chief at the US Embassy in Bishkek (a RFE journalist confirmed this to me and Manas produced his business card as proof. A request for comment to the diplomat’s official email address elicited the following answer: “You should address this inquiry to the Public Affairs section at the embassy”). Fearing for his life and desperately looking for safe passage to a third country—“I don’t fear the local intelligence services. I fear the Russian FSB”—he revealed everything he knew about Russia’s involvement in Ukraine to the US diplomat, in the hope that that would help him obtain asylum.

He often wondered out loud about the reason the US had reneged on the promise to help.

“He questioned me for four hours in a safe house I identified in Bishkek, as I didn’t want to be seen at the US Embassy. He recorded our conversation and I gave him a mobile phone memory card with all the documentation I had taken in Ukraine, including clips about military operations and evidence of Russian participation,” he told me during one of our many meetings after our first two-day encounter in Talas. “In the end, he asked me if I had a passport and could go to Almaty [in neighboring Kazakhstan], adding that we’d solve the problem very fast, but that he couldn’t promise anything concrete at that point.”

That was the first and last time Manas heard from the US diplomat. During meetings, he often wondered out loud about the reason the US had reneged on the promise to help. At times, his frustration would explode in fits of vodka-filled rage. During meetings, his tone would switch back and forth between conciliatory and threatening.

Chased by the Russians and shunned by the Americans, he felt isolated, cornered and most of all betrayed by everyone: the Russians for their propaganda; the RFE journalists for the interview; and the Americans for failing to deliver.

‘Swiss’ no more

Russia’s direct intervention in the Ukraine conflict sent shockwaves throughout Central Asia that are being felt to this day. While Kazakhstan for one supported Moscow’s March 2014 annexation of Crimea, the country’s leadership wasted no time in passing new legislation criminalizing calls for separatism the following month. In 2015 alone, at least three Kazakh nationals have been tried under the new law, with one receiving a five year prison sentence this November.

Kazakhstan can count on massive oil and gas wealth, however, to craft a diversified foreign and economic policy between Russia-led integration projects—Astana acceded to the EEU in January 2015—and other international partners such as the European Union and China. Kyrgyzstan has no such luxury and Russia’s overbearing presence is being increasingly felt in the cash-strapped country. Bishkek’s entry into the EEU was accompanied by the promise of a 1.2 billion USD aid package from Moscow.

At the ballot box in October, a majority of voters elected pro-Russian parties to Parliament and, only a few months earlier, the government scrapped a 1993 cooperation treaty with the US over a Human Rights Defender Award row. If there is little doubt that the US record on human rights in Central Asia is patchy at best, it is equally undeniable that these developments signal a worrying trend for Kyrgyzstan.

And it doesn’t end there. The new parliament is expected to pass a draft bill imposing tighter controls on NGOs and labeling foreign-funded activists as ‘foreign agents,’ as well as another banning ‘gay propaganda.’ Both are modeled on similar legislation adopted in Russia in 2012 and 2013, respectively.

This is a far cry from the country that little more than a decade ago could pride itself on the title of “Switzerland of Central Asia” and was considered one of the US’s closest partners in the region. Yet, Kyrgyzstan still boasts the most vibrant civil society in Central Asia and the Ukraine crisis has also seen a fierce, if limited, backlash against Russian interference.

The friend who rebuked Manas for his role in the war had gone to Ukraine to show solidarity with the protest movement in Kiev’s central square, the iconic Maidan. A number of prominent activists and opposition figures also traveled to the Ukrainian capital at different times. One met Manas a few days after the US diplomat. He didn’t mince his words: “he told me I should be arrested along with all those who went to fight in Ukraine,” Manas recalls (the activist confirmed this to me).

From color revolution…

Developments in Ukraine and Kyrgyzstan briefly appeared to run in parallel in the first half of the past decade. As a result of widespread electoral fraud, the two countries experienced massive demonstrations a few months apart that resulted in the toppling of long-serving corrupt regimes.

These events became known, somewhat optimistically, as the color revolutions. The Orange Revolution brought reform-minded Viktor Yushchenko to power in Ukraine in January 2005; the Tulip Revolution swept opposition leader Kurmanbek Bakiyev to the presidency in Kyrgyzstan in August of the same year.

From the start, the leadership in Moscow viewed the color revolutions through geopolitical lenses and has fought ever since to roll back what it considers Western interference in the internal affairs of its former Soviet periphery. In this context, the second half of 2000s witnessed a raft of legislation regulating NGOs—identified as a chief catalyst for inciting domestic subversion—which culminated in the 2012 foreign agent law. As recently as March 2015, President Putin warned against the possibility of a repeat of this scenario, this time in Russia.

Manas insists that he played a key role in the storming of the White House on March 24, 2005, which effectively marked the end of Askar Akayev’s—independent Kyrgyzstan’s first president—15-year rule. Along with other “revolutionaries” under his command, he secured the weapons cache of the Presidential guard located in the cellar of the building. “This is one of the main reasons why the 2005 revolution wasn’t bloody,” he brags. “We avoided a bloodbath. During the following days we also helped to reestablish order in the city,” where looting had spread in the ensuing chaos.

‘’[What’s happening in the] Ukraine is not a civil war, it’s an invasion. Russia has occupied and annexed the Crimea, and it controls the armed groups in the east.”

Hopes of a democratic transition were soon crushed, however. Newly-elected President Bakiyev took to running the country as his personal fiefdom, awarding government positions and profitable businesses to family, friends and cronies. Despite burnishing his revolutionary credentials in virtually every conversation, Manas occupied various positions in government institutions under Bakiyev, including a stint as assistant to Usen Sydykov, the then head of the presidential administration.

This was until his arrest in 2008. “I was detained on trumped up charges of possession of firearms and explosives,” he says. Manas argues that the real reason behind this was his outspoken criticism of Bakiyev’s authoritarian bent, which crystallized in his joining the opposition party Erdik Birimdik (‘National Unity’). The party’s then leader Ruslan Shabatoyev, a member of parliament, disappeared under mysterious circumstances in September 2008. Bakiyev’s rule was plagued by a series of high-profile killings that many believe were orchestrated by the President and his entourage. Shabatoyev’s body was found on the outskirts of Bishkek on October 1, 2009.

By the time unrest engulfed Kyrgyzstan once again in April 2010, this time against revolutionary-turned-autocrat Bakiyev, Manas was languishing in jail (he would be released the following year). Still, he maintains keeping a direct line of communication with his associates in Talas, where massive protests first broke out: “I knew the date set for the demonstrations was April 6th, so I organized my men in Talas via mobile phone. They kept me abreast of developments and, in turn, I gave them orders.”

While Russia’s direct involvement in removing Bakiyev is difficult to prove, observers note that Kyrgyzstan-Russia relations had hit a new low in mid-2009, when President Bakiyev recanted on his promise to close the Manas Transit Center in exchange for a 2.15 billion USD credit line from Russia. Instead, the US secured a lease extension for the airbase with a 3.5-fold rent increase to 60 million USD.

Moscow’s sudden imposition of custom duties on refined petroleum exports to Kyrgyzstan fuelled the energy price hikes that provided the trigger for popular unrest, against a background of rampant corruption and cronyism. Finally, once Bakiyev had been ousted, the Kremlin moved fast to give its blessing to the new leadership in Bishkek. As TIME magazine reported at the time, “it seems clear now that Kyrgyzstan will quickly return to Moscow’s sphere of influence after months of strained relations with Russia.” That remains the case to this day.

…to Russia’s invasion

If experts may still debate the degree of Russia’s meddling in Kyrgyzstan during the 2010 revolution, Manas has no doubt about the role it played in the war in Ukraine in 2014. “[What’s happening in the] Ukraine is not a civil war, it’s an invasion. Russia has occupied and annexed the Crimea, and it controls the armed groups in the east,” he keenly highlights.

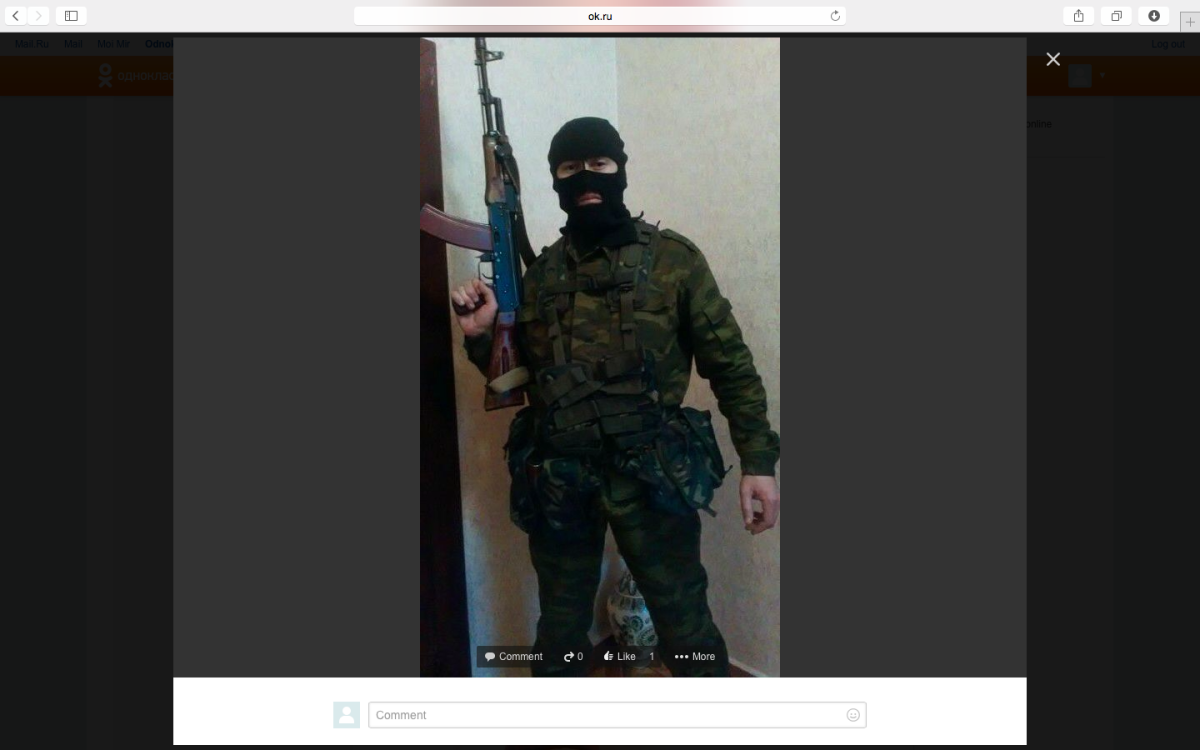

A graduate of the Military-Political Academy in Simferopol, Crimea, Manas revived his ties from Soviet times in order to join the fight in the Donbass region. He contacted an ex-commander from the Academy via Odnoklassniki—or “classmates,” a Russian social network widely used in the former Soviet Republics—who in turn put him in touch with a representative of a Cossack organization in Rostov-on-Don, Russia.

Over several mobile phone conversations en route, a Cossack going by the name of Vano provided Manas with the logistical and financial help to travel from Bishkek to the Russia-Ukraine border crossing at Izvarino via a combination of train and bus trips in August 2014. Before entering Ukraine, Manas received a last call from Vano: “he told me never to phone again from inside Ukraine and then instructed an FSB Colonel at the border to let me through,” he recalls (after his RFE interview, Vano allegedly took to calling Manas a “traitor” on Odnoklassniki).

On the other side, pro-Russian rebels had been in control of the crossing since June 2014. They took Manas to their headquarters in the town of Krasnodon, a 15 kilometer drive from Izvarino, where he stayed for about five days during which his credentials were checked. He was assigned to a special reconnaissance unit headed by a Kazakhstan-born Russian using the nom de guerre Che Guevara.

Manas explains that these forces consist of at least three separate formations that constitute what he calls a “hybrid army.”

During the night, he could hardly sleep due to the roar of engines from tanks and Ural and Kamaz heavy utility trucks rolling into Ukraine from Russia. Manas calculates that “during my stay, three to four thousand Russian soldiers passed through the town on 300 trucks, plus 40 tanks, dozens of heavy artillery pieces and multiple rocket launchers, and thousands of boxes with rifles, ammos, and supplies.” This confirms reports that appeared from mid-August 2014 onwards of reinforcements crossing from Russia into Ukraine.

Russia’s intervention extended to command-and-control of the rebel forces, too. Manas produced the original one-year enlistment contract he signed on November 25th, 2014, with some Major General Sergey Yurevich Ignatov, commander of the LNR People’s Police (another mercenary confirmed to me the contract’s authenticity). In summer 2015, Ukraine’s intelligence services revealed that Ignatov’s family name is actually Kuzovlev, Chief of Staff of the 58th Army in Russia’s Southern Military Sector, which borders the Donbass. Kuzolev is one of five Russian generals who played a key role in organizing and commanding separatist forces inside Ukraine.

Last time I saw Manas, he was at his wits’ end and he seemed resigned to a life on the run.

Manas explains that these forces consist of at least three separate formations that constitute what he calls a “hybrid army.” First, there are contract servicemen from the former Soviet Union, battle hardened soldiers who fought in the two Chechen wars, Transnistria and South Ossetia, wear special unmarked uniforms and call themselves ‘the army.’ Then, there is a special brigade positioned along the Russia-Ukraine border ready to intervene in the event of a rebel set back. And finally, there are volunteers recruited from other ex-Soviet Republics as well as locally, whom ‘the army’ calls militiamen. Manas belonged to the latter.

The battle for control of the strategic city of Debaltseve—a railway hub that connects Donetsk and Luhansk—best illustrates the key role Russia played in the conflict. “Without Russia, we could never have taken Debaltseve. Morale was low and the Ukrainians had dug in in trenches reinforced with containers, cement and iron bars against artillery fire,” Manas reminisces. “Had the Ukrainian army been allowed to break through at Debaltseve, it would have advanced and cleared all areas of rebel forces from there up to the Russian border. The war would have been effectively over.”

Instead, in the second half of January 2015, “the special brigade set itself up along the frontline and subjected the Ukrainians to the heaviest artillery barrage I’ve ever seen in my life. It was relentless.” This was common practice, Manas contends. “The Russians would use their superior firepower to obliterate the enemy. Only then would the rebels move into the area, for photo ops with journalists.”

By mid-February, the Ukrainian army had been forced to withdraw from Debaltseve in what the Guardian called a strategic victory for pro-Russia forces and a stinging defeat for Kiev. The withdrawal came only a couple of days after the entry into force of a ceasefire agreed in Minsk by the leaders of Ukraine, Russia, France and Germany with the mediation of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE).

When speaking of the militia commanders, Manas refers to them as “bandits,” each in charge of an area that he ran as his own turf with the help of a motley crew of undisciplined fighters. He mentions episodes of rapes and killings of captured soldiers—some involving him—that may amount to war crimes. His recollections expose a leadership marred by internal rivalries and dependent on Moscow. He argues that the assassination of key rebel commanders opposed to the Minsk Accord were orchestrated by LNR head Igor Plotnitsky with the tacit consent of the Kremlin, the real master of puppets in Donbass.

As if to prove his point, he discloses that before the mysterious killings Viktor Penner, Plotnitsky’s advisor, had asked him to become part of an “operational intelligence unit, as Plotnitsky feared that a rebellion against his authority was in the offing. We would look for enemies within our own forces and, if we found an opponent, we’d kill him.” That is when he decided it was time to leave.

Last time I saw Manas, he was at his wits’ end. All his attempts to leave the country had come to naught and he seemed resigned to a life on the run. His tone was more conciliatory than threatening, but as usual self-criticism was conspicuously absent. It was everyone else’s fault that he had driven himself into a corner. In his mind, he was still a misunderstood Kyrgyz hero, as the pseudonym he had chosen for himself made abundantly clear (the Epic of Manas is considered the national heritage of the Kyrgyz people).

Apparently, this is not so uncommon. A former Russian volunteer in eastern Ukraine interviewed by Dozhd TV channel stated that “most of those who came back either went on fighting, but for Kiev, or were jailed. They get into fights with the police or other people, trying to prove they are heroes back from the war. But come to think of it, are we really heroes?” Addressing President Putin, he concludes that the war “isn’t worth it.”

Just how not worth it all was becomes painfully evident on assessing the state of the Donbass region today. “The war has come and gone, leaving behind poverty and pain,” writes Novaya Gazeta special correspondent Pavel Kanygin.

If the conflict has passed its peak intensity, the situation on the ground remains extremely volatile, as recent incidents show. The media spotlight may have moved on, but left behind are the shattered lives of the thousands upon thousands of civilians who have to pick up the pieces.