Five men had lit a fire outside the Social Security offices in Nikaia in the middle of a January night. They were retirees, former office workers or manual laborers, unshaven and down at the heels. They started gathering there at three in the morning so they’d be the first to see the doctors before it got crowded and the line stretched all the way to the sidewalk. They didn’t know one another and none of them bothered to introduce himself—they had other things on their minds. Besides, their names weren’t important. What mattered was the order, that the order of the line be strictly maintained. Which is why each of the men thought of himself and the others as numbers in a list that would keep growing as the night advanced.

They were five men but also five numbers.

That was one of the things they had on their minds.

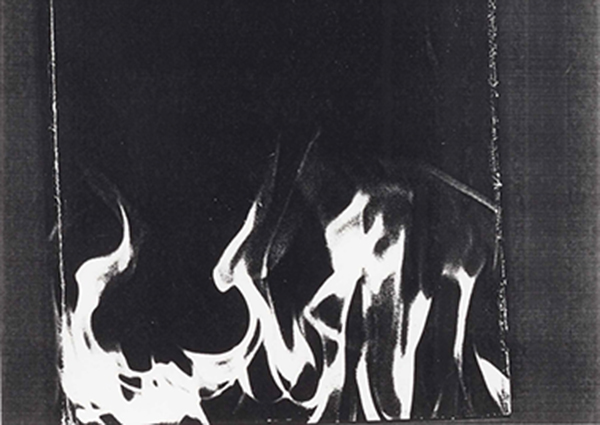

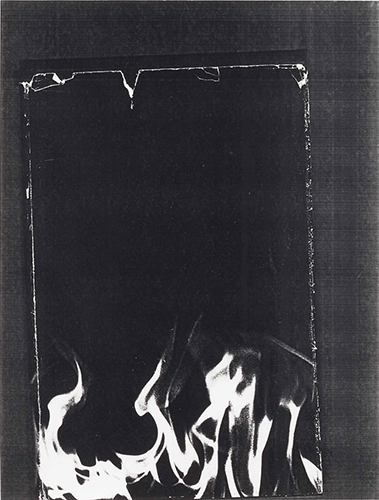

They had lit a fire on the sidewalk outside the front steps of the building.

Winter, bitter cold, a night that seemed to stretch on forever. It had rained early that evening and now the damp had turned to frost that sparkled like silver dust on all the parked cars. At first they paced up and down on the sidewalk to get warm, watching silently, with a kind of awe, as their breath rose into the darkness like smoke signals. Then the first man to have arrived, number one, who had cataracts and was almost blind in his right eye, had an idea. They could light a fire with some wooden pallets and cardboard boxes that were sitting next to a Dumpster on the street. The others immediately agreed because they were all very cold. One of them remembered that on his way there he’d seen a bunch of barrels outside of a building site on the next street over. He suggested they bring a barrel over and light the fire in it. They agreed to that, too, because they needed some way to keep the fire going until morning—that was another thing they had on their minds.

Then they all gathered around the barrel and stretched out their hands and watched silently as the flames leaped before their eyes.

Two of the men went to get the barrel, revolving it heavily over the sidewalk, and set it in front of the steps of the Social Security building. Then number three, a heavy-set man in his seventies with a growth on his intestines, broke up one of the pallets and stacked the planks in the barrel. Beneath the planks he’d already put some little branches he pulled off the mulberry tree on the corner. They lit the fire with a newspaper. It wasn’t easy, the wood was damp. But when the fire finally got going, they ripped up two cardboard boxes and tossed the pieces on top of the wood. Then they all gathered around the barrel and stretched out their hands and watched silently as the flames leaped before their eyes. Everyone except for number two, who had brought a small folding stool from home because he suffered from sciatica and couldn’t stand for very long. He opened the stool and sat down with his legs crossed and, looking absentmindedly at the fire, murmured in a husky voice as if chanting:

In Nios where they sent me

I saw churches and windmills

and was welcomed

by a flock of fleas

The drivers on Petros Rallis Street kept slowing down to gawk at them. But numbers one through five didn’t care. They were very cold and knew that without a fire they wouldn’t make it out there all night on the sidewalk. They didn’t care what people thought, they had other things on their minds. They were tired and sick. They were old. They had other things on their minds.

Number three tore up a box and threw the pieces into the fire. He stirred it with a thick branch and then looked at the guy sitting on the stool.

You like it, huh? he asked.

What do you mean?

For other people to work while you sit there scratching your balls.

I told you guys, I’ve got a problem with my back. Didn’t you hear?

We’ve all got something. That’s why we’re out here tonight. Get up and help, you old shit.

Don’t talk to me like that, said the man on the stool. Tough guy. Who do you think you are, telling us what to do?

I know how your kind is, said number three. Lazy bums who like to have a good time. I’ve met plenty of you in my day. You just make sure to cover your own ass, and everyone else can go fuck themselves for all you care.

Come on, that’s enough, broke in the man who’d arrived last, number five. He was the youngest, around sixty. He wore thick glasses and his teeth, crooked and with large gaps between them, looked like a broken fence. He spoke with a lisp, too. Come on, stop, he said. We’ve got enough going on, the last thing we need tonight is a fight.

Gap-mouthed fool, number three shot back, and went to get another cardboard box.

Number two got up off his stool then sat back down and crossed his legs the other way. He lit a cigarette and blew the smoke out hard. His hands were trembling. He took his Social Security booklet out of a plastic bag and started flipping through it noisily. He was muttering something to himself. Now his legs were shaking too. Then he closed the booklet and leaned over and pointed to number three, who had bent down next to the Dumpster, and asked the others in a whisper:

Is that guy crazy?

No one spoke. They didn’t even turn to look. They kept their hands stretched out in front of them and stared at the flames wondering whether there was enough wood and cardboard for the fire, if they would manage to keep the fire going until morning.

They carried their Social Security booklets and identity cards. They carried packs of tissues and keys and coins and a few bills—some in wallets, some shoved into their pockets. Each carried a bottle of water, pills, and capsules for his various ailments. Number five, who’d had rheumatism for years, carried a large brown envelope with X-rays inside. Almost all of them carried lighters or matches or extra cigarettes to help them stay awake. Two or three carried bus passes or tickets for the trolley or metro. Number four, who was sixty-eight years old but had thick gray hair and a thin gray mustache, carried stones in his kidneys and a small black comb in his coat pocket. Number three carried a pair of prescription glasses that he never wore in front of other people because he was embarrassed. Four of the five carried cell phones. Number two, who had brought his folding stool from home, carried in his wallet a photograph of his son who had died the previous month in a car accident in Halkidona. Number one, who was almost blind in his right eye, carried a booklet enumerating the miracles and visions of Saint Efraim the Martyr. He read two or three pages a day, with difficulty, to gather strength or hope or to forget his troubles.

All of them carried secrets, hidden sins, and things they rarely—or never—showed to anyone else.

They all carried years of hard work on their backs. They carried deprivations and dreams that hadn’t come true. They carried the weight of the time they had spent with their wives and children. They carried compromises they had accepted, vows they had broken. They carried betrayals they had committed and others they had sustained. Deep down each carried fear and stress and worry about time and illness, which came like conscientious gardeners to trim a bit off their lives each day.

They were poor people, with debt to the banks and unpaid bills.

One of them owed money to a loan shark.

Two or three of them carried lottery tickets, scratch-offs, and quick picks.

All of them carried secrets, hidden sins, and things they rarely—or never—showed to anyone else.

Number one, who had glaucoma and was almost blind in one eye, carried a bracelet made of elephant hair that a woman had given him many years ago at the airport as she was leaving for South Africa.

Number two carried the dog tag his son wore around his neck while a conscript in the army.

Number three had carried a Kershaw knife ever since the night he’d seen two druggies beating an old man black and blue for his money down under the bridge.

Number four carried a key chain with the keys to his family house on Aegina, which he’d been forced to sell for practically nothing.

The one who’d arrived last, number five, carried the coin he’d found in the New Year’s pie five or six years ago. It was the only time in his life he’d gotten the coin in his slice and for a while he carried it around for good luck. At some point he got a hole in the pocket of his winter coat and the coin fell into the lining and he never went to the trouble of fishing it out. By now he’d forgotten it altogether.

They carried lots of old songs, lots of images and memories from the days of their childhood. They carried a nostalgia for the things of the past, a nostalgia that became more and more bitter with the passing of time, and instead of filling them with joy now only made them feel older and more incapable.

They carried the smells of their homes. The stale smoke from the coffeehouses they frequented. The dirty air of Nikaia. The scent of bitter orange trees blooming at Easter time. There were times when they thought they carried the whole city inside them, streets named after forgotten homelands—Delmisos, Sinasos, Nicomedia—and others after the honored dead—Alekos Mouhtouris, the Heroes of Grammou, Armenian Fighters—and the side streets where refugee houses sat hunched in the shadow of six- or seven-story apartment buildings. Sometimes they felt as if they carried city squares with broken benches, churches and graveyards and old outdoor cinemas that had been turned into supermarkets and nightclubs.

They carried so many images and voices, of the living and of the dead.

All of them, but some more than others, carried a deep hatred of politicians and doctors and the civil servants who worked at the Social Security office—for anyone they could blame for the fact that they were sitting here tonight like bums on the sidewalk in the freezing cold far from their homes.

Two or three carried a deep hatred of themselves, too, for being so small and insignificant.

One carried his hatred of God, who had proven himself to be even harsher and more unjust than people.

They carried the weight of their weakness, the weight of time, of the illnesses that ate at their bodies.

Above all they carried a silent fear but a secret longing for the day that was dawning and all the days that would dawn after that.

Every so often someone brought a cardboard box or broke a pallet and threw the pieces into the fire. The drivers passing by slowed down and looked at them. Some shook their heads, others honked, either in greeting or with derision. Most of the people in the cars were young, couples or groups of men who were probably headed home after a night out.

The one on the stool, number two, carried a bottle of tsipouro in a plastic bag from Galaxy Supermarket. He opened it, took a swig, and held it in his mouth before swallowing. The previous week he’d sworn on his son’s bones that he would never drink again. Of course, he knew the oath was no good since he’d been drunk when he gave it. But now, as the tsipouro flowed through him, burning all the way down, he felt the hair on his nape rise and something cold slap him on the back. He shuddered.

Hey guys, he said. Guys, why don’t we call the stations?

What stations?

The stations. TV. So they’ll come and show everyone what a sorry state we’re in. How the little guy is sitting here suffering out in the cold. Fuck Social Security and all those government ministries.

You know, it’s not a bad idea. It might just—

Forget it, big guy, said number three, who was stirring the fire with a branch he’d pulled off the mulberry tree. I don’t like the sound of it.

Why?

Because. I’m not going to become a spot on TV. I’ve got my dignity.

The man on the stool started to laugh.

Hear that, guys? The gentlemen over there’s got his dignity. Why don’t you tell him pass some over to us if he’s got any to spare?

The others laughed too.

Number three looked at them and then pointed with his branch at the man on the stool.

Watch it, you cripple. Don’t mess with me, because I dance a tough dance.

Are we going to go through all that again? shouted number five, the one who’d gotten there last. Enough already. Fighting isn’t going to get us through the night.

Then he turned to number one, who was standing to the side reading his book, his lips moving as if he were talking to himself.

You started to say something earlier, he said. Come over here so we can all hear.

Number one closed his book and slipped it into his coat pocket and drew closer to the fire. The corneas of his eyes were white from the cataracts, the pupils almost entirely covered. He’d seen how the others had looked at him—he’d seen lots of people looking at him like that—and for a moment he thought it was time he bought a pair of sunglasses to wear when he went out, even at night. He didn’t like for people to look at him that way. He didn’t want to scare people and didn’t want them to pity him.

Go on already, said number three. Or do you want us to beg?

They all gathered around the barrel and stretched out their hands, very close to the flames.

I was headed home late one night from Amfiali. It was cold and foggy, but I decided to walk so I wouldn’t have to pay for a taxi. Suddenly somewhere around the water plant I hear a crash and all of a sudden there’s a violin lying in front of me. I was terrified, my knees gave out beneath me. It was a close call. If I’d been two meters ahead of where I was it would have smashed me right on the head. I look up. There’s a huge apartment building so tall you get dizzy just looking at it. One of the balconies has a light on. I hear some noises and a woman shrieking. Everyone else is asleep, and no one wakes up and comes out. There isn’t a soul in the street, either. And the fog is so thick you could barely see a thing.

Look at that, I said to myself. That violin won’t ever make music again. No song will ever come from its strings.

A few minutes later, I see a young guy come tumbling down the stairs of the building. He’s wearing a wifebeater and he’s got one of those things on his arm, what do they call them, a tattoo. Barefoot and with his hair all crazy and the kind of eyes that make your blood freeze. But I wasn’t afraid.

What’s going on, man? You almost killed me.

Go fuck yourself, grandpa, he answers. Not angrily but like he might start crying any second.

Then he drops to his hands and knees and starts gathering up whatever he finds on the sidewalk. The instrument is in thousands of tiny pieces. The strings in one place and the wood in another, it’s a total mess. But the young guy picked up every piece, didn’t leave a single splinter. Then he held the whole mess all in his arms and sat down on the stairs. He was holding the violin in his arms as if it were something alive, some baby or little kid. I was standing off a little ways and watching him messing with the pieces and trying to put them back together again. Look at that, I said to myself. That violin won’t ever make music again. No song will ever come from its strings. That’s a damned sad sight.

The violin’s a beautiful instrument, said number four, the one with kidney stones. My father, may his soul rest in peace, used to cry whenever he heard the violin. He was a refugee from—

It’s nothing like the accordion, though, broke in number two, shifting on his stool. There’s no instrument like the accordion. I tried everything to get my son to learn to play it, but he wouldn’t listen to me. He never listened to me. He didn’t listen to anyone. That’s why he.

He took a swig of tsipouro and the same shiver ran down his back again. He stood up from the stool took the comb out of his pocket and started running it through his hair, which felt hard and prickly like thorns.

Number three struck the branch he was holding against the side of the barrel, hard.

Will you guys shut up already? Come on, man, tell us what happened next.

So I was thinking those things, number one continued, but I didn’t say a thing. I just watched him stroking that violin and didn’t let out a peep, not a word, as if I were a priest who’s just given a dying person his last rights. On the one hand I felt sorry for him and on the other I was afraid of saying something he might take the wrong way. Because he was clearly pretty upset.

Hold on a sec, broke in number three. I missed something. Who’s the dying person?

Number two, the one with the tsipouro, started to say something but then bit his tongue and bowed his head.

What’s he laughing at? Didn’t I tell you not to get on my nerves? Didn’t I tell you—

We all heard you just fine, said number two. You dance a tough dance. So why don’t you show us your moves? You’re all words. Come on, let’s see what you’ve got!

Number one touched him on the shoulder. Please, he said. In the light from the fire his eyes were a strange yellow color. Number two shuddered. He hunched over on his stool and didn’t say anything else.

Then number one turned to number three.

When a priest goes to give a dying person his last rights he’s not supposed to talk, he explained. Not before and not after. Otherwise, it doesn’t work. I didn’t know either. I found out when my Maria died. I called the priest from the hospital and he came and left without saying a word. I’d been in the hospital for a week from morning until night and hadn’t shut my eyes once. I begged him to tell me something, to say just a few words, it didn’t matter what. Aren’t there moments in your life when you need to hear something? Moments in your life when you really need some human conversation. When you need to hear something so as not to.

He stopped and took a gulp of breath as if he were drowning. By now he was yellow all over. No one said a word. All you could hear was the roar of the fire and the crackling of the wood in the barrel.

What happened next? asked number five. You didn’t finish the story. What happened next?

I hear a voice overhead. I look up and see the top half of a woman hanging over the balcony railing and she’s shouting and shouting. You wouldn’t believe me if I told you all the things that came out of her mouth. I couldn’t see her face or anything but she had long black hair that was hanging loose in the air. It felt like you could reach out a hand and touch it. The things that hair reminded me of. Anyway. She was cursing up a storm, it’s one thing for me to describe that language and another for you to hear for yourself. My jaw dropped, since I’d never heard a woman cursing like that. And the young guy turns to me and says:

You hear that, old man? It’s not enough that she killed my violin, now she’s swearing at me, too. But you should stick around for the next episode. I’m going to go back up there and throw her TV off the balcony. First it was her turn and now it’s mine. Aren’t I right? Don’t worry, I’ll even things up. Stick around and you’ll see what kind of party we’re going to throw here tonight.

That’s what he said but he didn’t budge at all. He just sat there and messed with his violin, stretching the strings and trying to piece together the broken pieces of wood. But it was no use.

The nail on one of his toes was black.

You’re going to lose that nail, I say to him. It hurts a lot to have a toenail fall off.

I don’t know what got into me next, but I turned to him and say: Don’t give up, kid. You have to have hope. If you fall down you have to pick yourself right back up again.

Okay, old man, he says. Whatever you say.

And he actually stood up with the violin in his arms and started to walk away. At the door to the building he stopped and said to me:

You know something, old man? It’s not the fall that kills us but the sudden stop at the end. You understand? It’s the sudden stop that kills us.

I thought about it for a minute.

That’s a big thing you said, I finally tell him.

But he’d already gone. I turn and see him climbing the stairs inside the building with his head bent and then I couldn’t see him anymore.

I walked as far as the corner and waited. I can’t tell you how anxious I was. I kept thinking he was going to come out onto the balcony cradling the television and throw it into the street and then who knows what might happen with that woman. Because I was worried about her, too, even after all the curses she’d dumped down on him. I was thinking about how young they were. Such young people, just kids really, so where does all that hatred come from?

Then what happened? asked number three, who had almost put out the fire from stirring it so much. What happened next? Did he throw the stupid television over the edge? Maybe he pushed his lady friend, too? She deserved it, that’s for sure.

Nothing happened, said number one. I waited there for a while but nothing happened. I didn’t even hear the woman’s voice again. Then I saw the light go out on the balcony and everything got quiet.

What kind of bullshit is this? number three shouted, hitting the branch against the barrel again. Come on, tell us what happened next. He can’t have done nothing. No way. What kind of man is he?

Yeah, he must have done something, said number five, who’d taken off his glasses and was cleaning them with his scarf. He can’t have just left it at that.

Nothing happened, I’m telling you. I waited there in the fog for about ten minutes and smoked a cigarette but nothing happened. Then I left but didn’t go straight home. I’d been so shaken up I couldn’t sit still. So I started walking down toward the port. On the way I thought about what the young guy had said about falling and the sudden stop. I had lots of ready answers in my head but none of them suited the situation. As I walked I watched the lights from the port grow in the mist. At first they were beautiful. Then they got scary.

A car with a broken exhaust pipe passed by on the street. The clattering startled them all.

Go fuck yourself, you asshole! shouted number three.

Then he turned to the man with the tsipouro.

Is that how things work in your village? Yiannis treats and Yiannis drinks? Pass that bottle around, you pig.

He grabbed the bottle and poured some tsipouro into his mouth without letting the rim of the bottle touch his lips. Then he handed it to the next guy. They each took a swig.

A real man would have done something. Instead of sitting there and whining over his broken violin.

We could have done without that story, the man on the stool said to number one. What were you thinking? You crushed our morale. Fuck it.

Yeah, said number four. He’s right. He looked number one in the eye and then turned to look elsewhere. You crushed our morale. A real man would have done something. Instead of sitting there and whining over his broken violin. You didn’t handle the whole thing very well, either. You didn’t give him the best advice.

Number one looked at each of them in turn but didn’t speak.

Number three stirred the fire with his branch and then threw it in the barrel.

Man, if I’d been there I’d have known what to do, he said. But what do you expect. The world is full of fairies these days. There’s not a single man left with a real dick anymore.

He pulled a switchblade out of his pocket and weighed it in his palm. He pressed a button and the blade sprang up, glinting in the firelight.

I know what I’d have done, he said.

Number one silently looked at each of the others with his sick eyes. He’d shrunk beside the barrel with his hands wrapped around his upper arms and hiding his face in the collar of his coat. His shoulders were shaking.

What kind of people are you, he finally said.

For a while no one spoke. In the glow from the fire their faces seemed transformed, full of shadows that kept changing shape. Then someone, number three, took a step backward and tilted his head until he was looking straight at the sky. It was gray and blurry like a TV screen with no signal. He looked at the sky with such concentration, almost motionless, as if he were trying to figure out how much the sky weighed or to calculate the distance between him and the sky, which seemed to have sunk down so low that it was resting on the roofs of the buildings.

This night just won’t end, he said. What time is it, anyway?

And then he said:

These days I keep on dreaming that I’m falling. That I’m tripping on something and falling. I’m woken by fear with my heart pounding so hard I think it might burst or come flying out of my ears or something. It’s a terrible thing to be falling. Really. Terrible.

Now the others were looking up, too. They had all tilted their heads back and were staring up at the sky.

What’s worse, though? asked number one. An endless fall or a sudden stop?

You’ll have to tell us. You seem to be the reader here.

I don’t know. The things I read don’t jive with the things I see. Or with the things I think. Nothing jives with anything.

The fire went out. Someone went to get another pallet. It was the second to last. And there weren’t many boxes left, either.

They all huddled around the barrel. Even number two, who could now feel a deep pain shooting up from his heels to the middle of his back, got up from his stool and stood among the others. They all crowded together with their hands stretched close to the fire. Very close to the fire. Their bodies were touching, their elbows and arms. They jostled and pushed against one another as if they wanted to work through their heavy winter clothing and touch one another’s skin. They came as close to one another as they could get. But instead of warmth they felt a shiver pass from one body to the next—they felt a cold current leaping unrestrained and breaking the circle of bodies heedless of the fire that was burning so close to them, so close to their hands, so close to their chests and faces.

Early in the morning, passing by on my way to work, I found them still standing in a circle around the barrel. By then others had come and were waiting on the sidewalk, old men, women, foreigners. But they were still gathered around the barrel, five men with faces white from sleeplessness and cold, watching silently as the fire slowly died out in the freezing light of day.