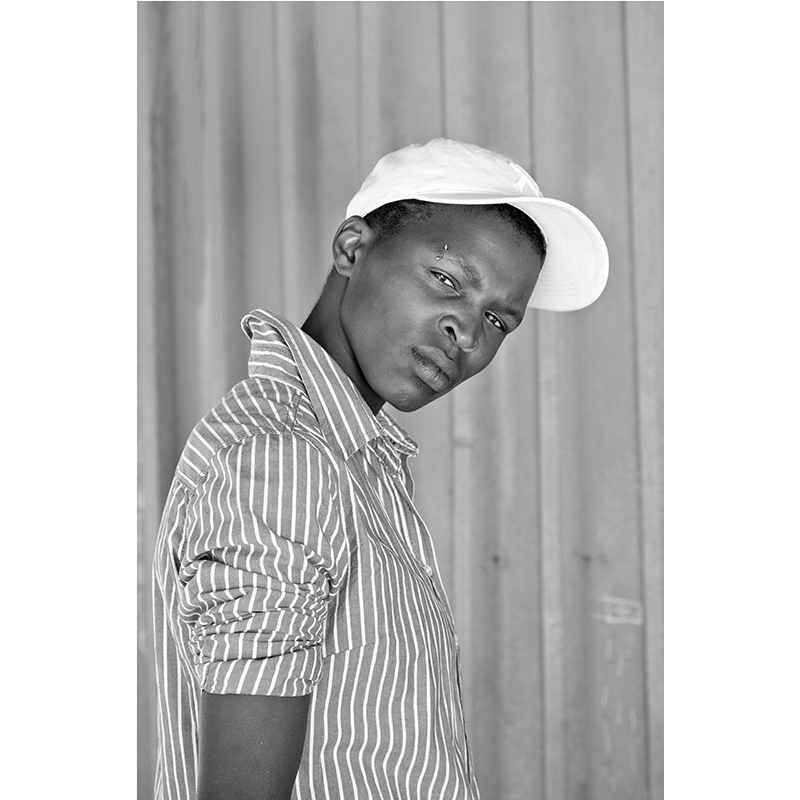

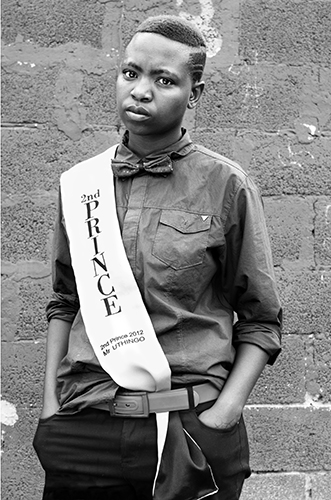

Zanele Muholi (South African, born 1972). Lithakazi Nomngcongo, Vredehoek, Cape Town, 2012, 2012. Gelatin silver photograph, 34 x 24 in. (86.5 x 60.5 cm). © Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of Stevenson Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York.

In 1975, the photographer Joan E. Biren was on vacation when she took a black-and-white self-portrait in Dyke, a small Virginia town.

Biren is smiling, standing in a sweatshirt and jeans next to the sign, which spells out the town’s name in caps. In the early seventies, she was one of the first out lesbians in the United States. “I mean, you assume you’re not the only one but you don’t know,” she said in a 2004 interview looking back on her career for the Women’s History Archives. This image documented a radical shift in photography in which queer artists and documentarians began to archive their experiences in front of and behind the camera, at a time when feminism was overwhelmingly a straight white woman’s game. In addition to herself, Biren captured mixed-race lesbian couples and black lesbians who were often sidelined from the forefront of movements for change in the US.

Zanele Muholi was born three years before Biren took that now-iconic photograph, and the South African photographer, who describes herself as a “visual activist,” counts Biren as an influence. Muholi grew up in Durban and studied photography in Johannesburg, where she began working for an online magazine covering LGBTQI issues as a reporter and photographer before co-founding the Forum for Empowerment of Women in 2002, an LGBTQI rights organization that gave black lesbians a (safer) space to meet and organize. Two years later, she created her first short film, Enraged by a Picture, which documented an early show at a Johannesburg gallery and screened at the Tate Modern in London this July as part of its series The Film Will Always Be With You: South African Artists On Screen.

Muholi’s current show at the Brooklyn Museum, Isibonelo/Evidence, on view through November 1, is the most comprehensive US exhibition for the artist to date. Organized by curators Catherine J. Morris and Eugenie Tsai, the multi-part show focuses on making the invisible visible forty years after Biren’s photo was first taken. The exhibition includes more than eighty works produced between 2007 and 2014 that confront what it means to be a LGBTQI person living in South Africa today, in the post-apartheid era. This is the next generation of queer youth, grappling with hatred from family members, former friends, and current neighbors, despite the fact that same-sex marriage has been legal in South Africa for almost a decade.

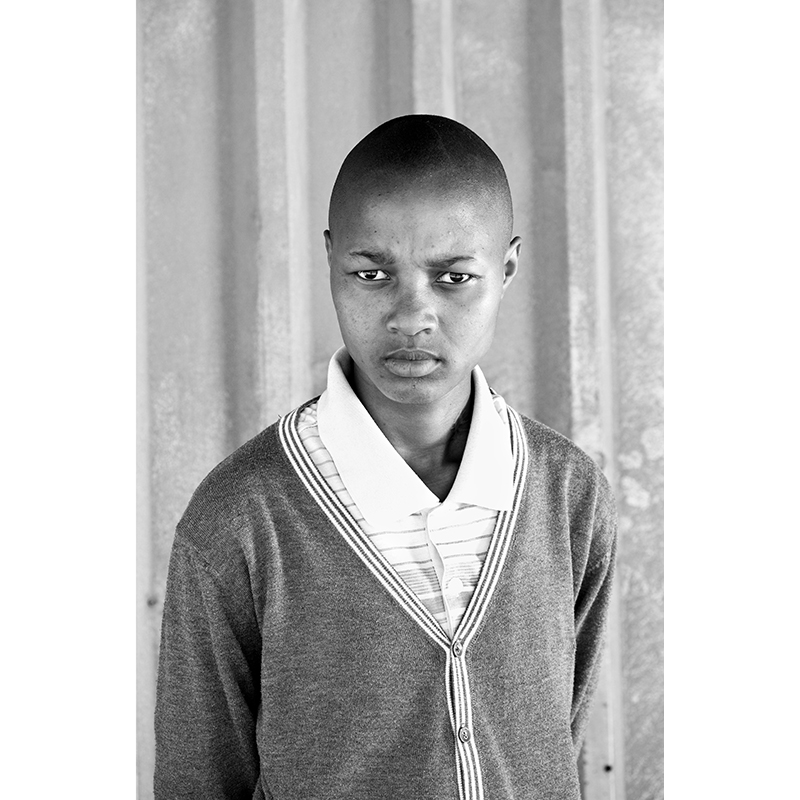

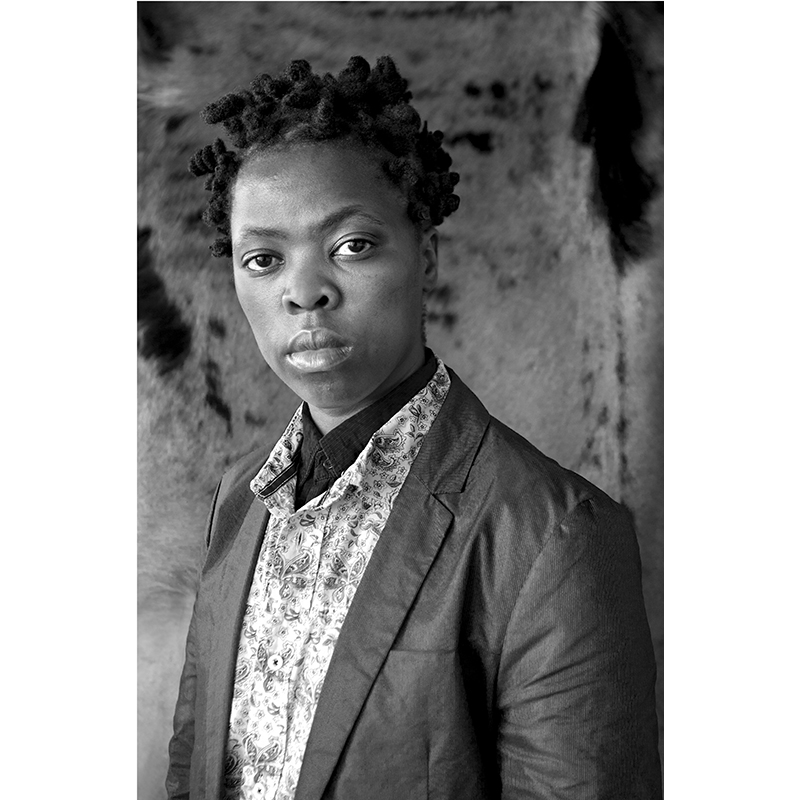

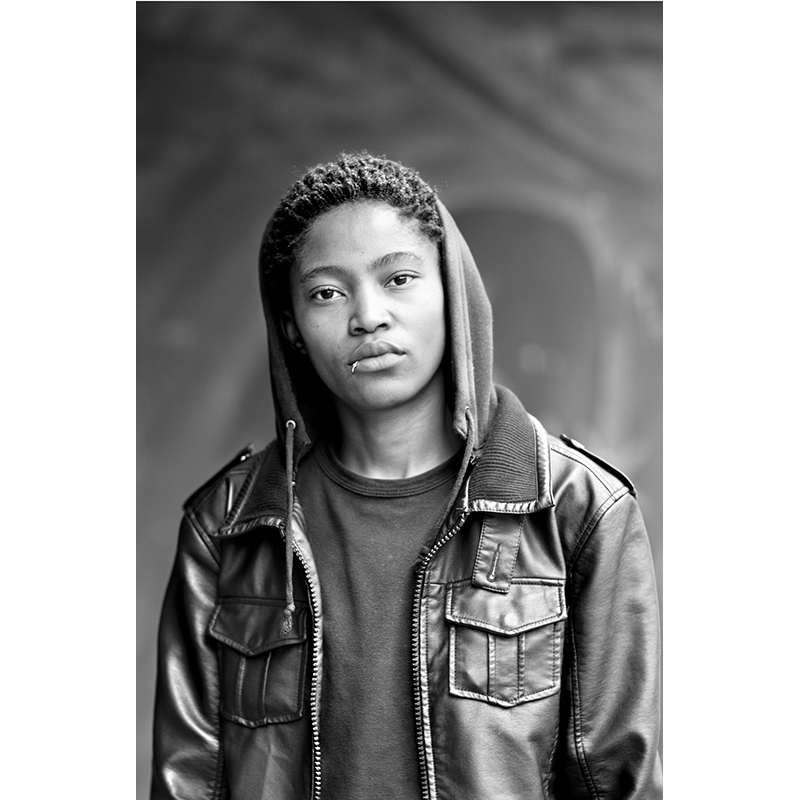

These subjects aren’t asking for your sympathy; they are acknowledging their own place in history, which has been hard-won.

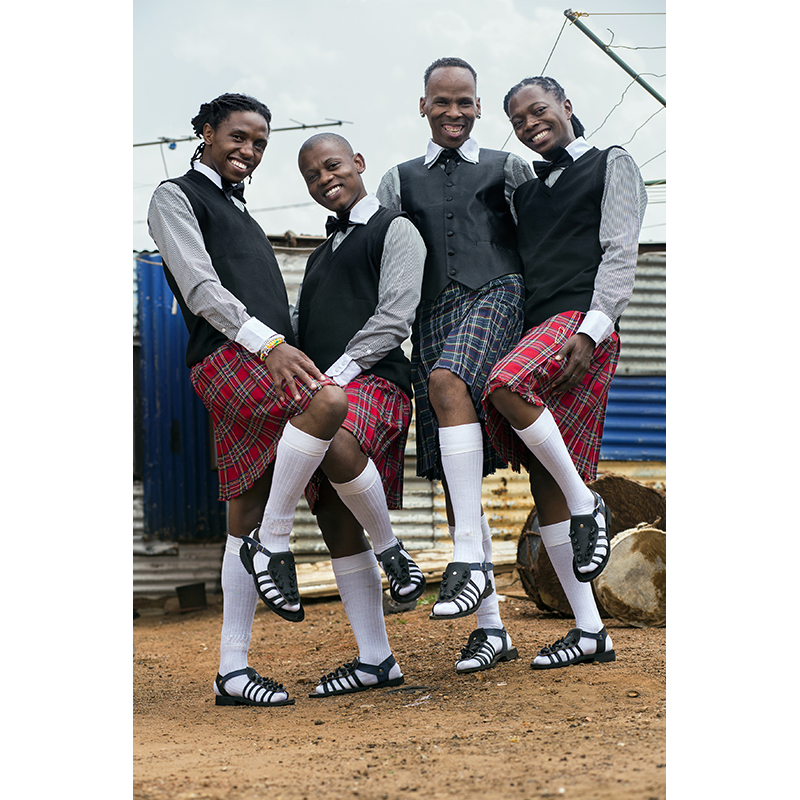

Photo: © Anders Sune Berg.

The first room features the photographer’s Faces and Phases 2006–2014 series, where rows of black-and-white images of lesbians, transmen, and gender-nonconforming individuals take up an entire wall. Faces and Phases—previously shown at dOCUMENTA 13 in Kassel, Germany, in 2012 and at the South African pavilion at the 55th Venice Biennale a year later—builds on Muholi’s idea that black women are often erased from established queer and women’s histories. “The mainstream archive and the women’s canon lack visual, oral and textual materials that include black lesbians and the role they have played in our communities,” she writes in the introductory text to the series.

Muholi’s subjects are able to challenge the camera with seeming ease. They exist in myriad forms—as coy and playful, like the woman wearing a “102%” t-shirt featuring interlocking female gender symbols, or as more serious, like the image of Collen Mfazwe, hands in pockets, proudly wearing a sash declaring her the 2nd Prince of Mr. Uthingo, 2012. These subjects aren’t asking for your sympathy; they are acknowledging their own place in history, which has been hard-won. Christie van Zyl, whose portrait is included in the exhibition, writes on Inkanyiso, Muholi’s visual arts and media advocacy blog, that the photographer asked her to pose in “the space between arrogance and innocence.”

The adjoining wall displays news reports about lesbians and gender-nonconforming individuals who were brutally killed in recent years. It faces another wall, full of chalk-drawn messages from the photographer’s subjects detailing their treatment by fellow citizens, who do everything from taunting them in the streets to resorting to “corrective rape.” Twenty-one-year-old Mamello “Meme” Motaung, a young lesbian in South Africa, writes, “Mamello is a South Sotho name meaning perseverance.”

“Can somebody just write about the dangers of taking these photographs. The fact we have to fear for our lives while we try to archive history.”

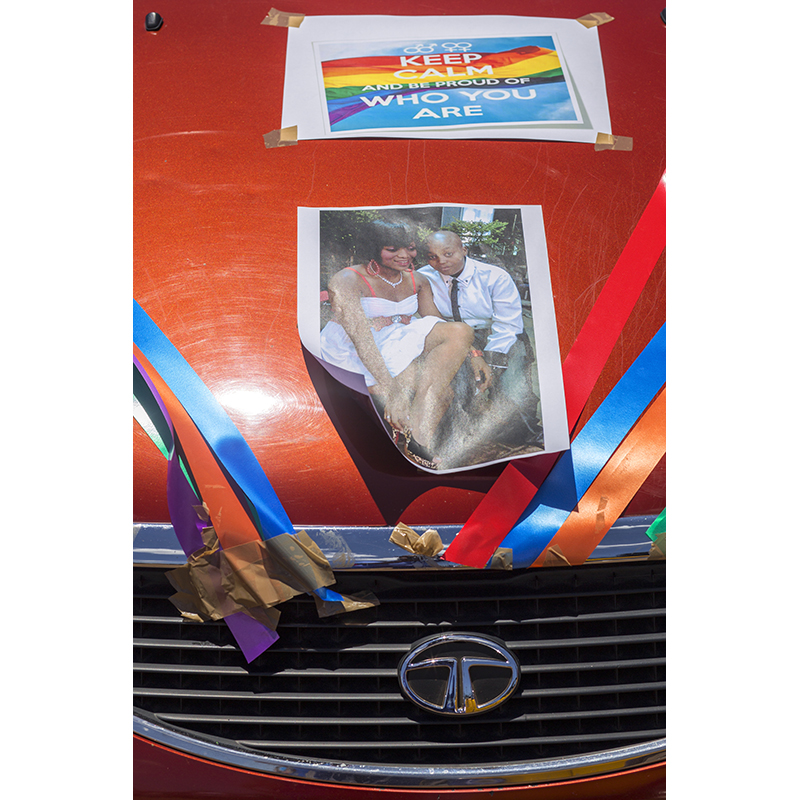

Zanele Muholi (South African, born 1972). Ayanda & Nhlanhla Moremi’s wedding III. Kwanele South, Katlehong, 9 November 2013, 2013. Chromogenic photograph, 18 11/16 x 14 in. (47.5 x 35.5 cm), framed. © Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of Stevenson Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York.

But just around the corner viewers are met with a celebration: Muholi captures young South African couples marrying with the support of friends and family in her new series, simply titled Weddings. Across the way is Being Scene, a deliberately out-of-focus video of Muholi and her partner having sex, in which blobs merge and separate and sound is an afterthought. (Video does not seem to be Muholi’s forte, but her activism here holds stronger than the aesthetics.) And in a darkened room off the side of Weddings lies a decorated coffin with Muholi’s framed portrait sitting in it. She is quoted on the Inkanyiso blog: “Can somebody just write about the dangers of taking these photographs. The fact we have to fear for our lives while we try to archive history.”

Like Biren, Muholi does not want to capture images so as to be included in historical footnotes; she wants to ensure that these individuals, and that she herself, are a part of history—period. Her subjects are lesbian, trans, and queer, but although they are part of a distinct community, they are no longer the silent minority.

Many LGBTQI people worldwide are still unable to live an authentic life, even in countries where same-sex marriage is protected by law. This summer, as we finally acknowledge marriage equality in the US, Muholi’s exhibition brings much-needed visibility to deeper issues of racism, misogyny, and erasure, reminding us that this is just the beginning.

Kathleen Massara is the managing editor of Artnet.