In 1979 around 400 armed fundamentalists led by Jahayman Uteybi pulled out their guns and laid siege to the Grand Mosque in Mecca. It was November 20, the last days of that year’s Hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca, and while many of the million visitors had packed up and left, thousands remained within the grounds, praying, sleeping, talking.

Saudi forces, incapable of dislodging the fundamentalists from the city’s underground tunnels, had to call on the expertise of French elite units to break the deadlock. By the time the siege ended two weeks later, the walls of the Grand Mosque were pockmarked with bullets holes, and the ground ran with blood and entrails. The Saudis declared afterwards that 127 of their armed forces had been killed, 117 of the rebels and 26 of the civilians. Independent observers put the death toll at more like 1,000.

That the incident has been excised from school textbooks in Saudi Arabia is unsurprising—the kingdom is hardly one that embraces open criticism. That the siege of Mecca was not mentioned in the new exhibition about the Hajj at the British Museum was rather more surprising.

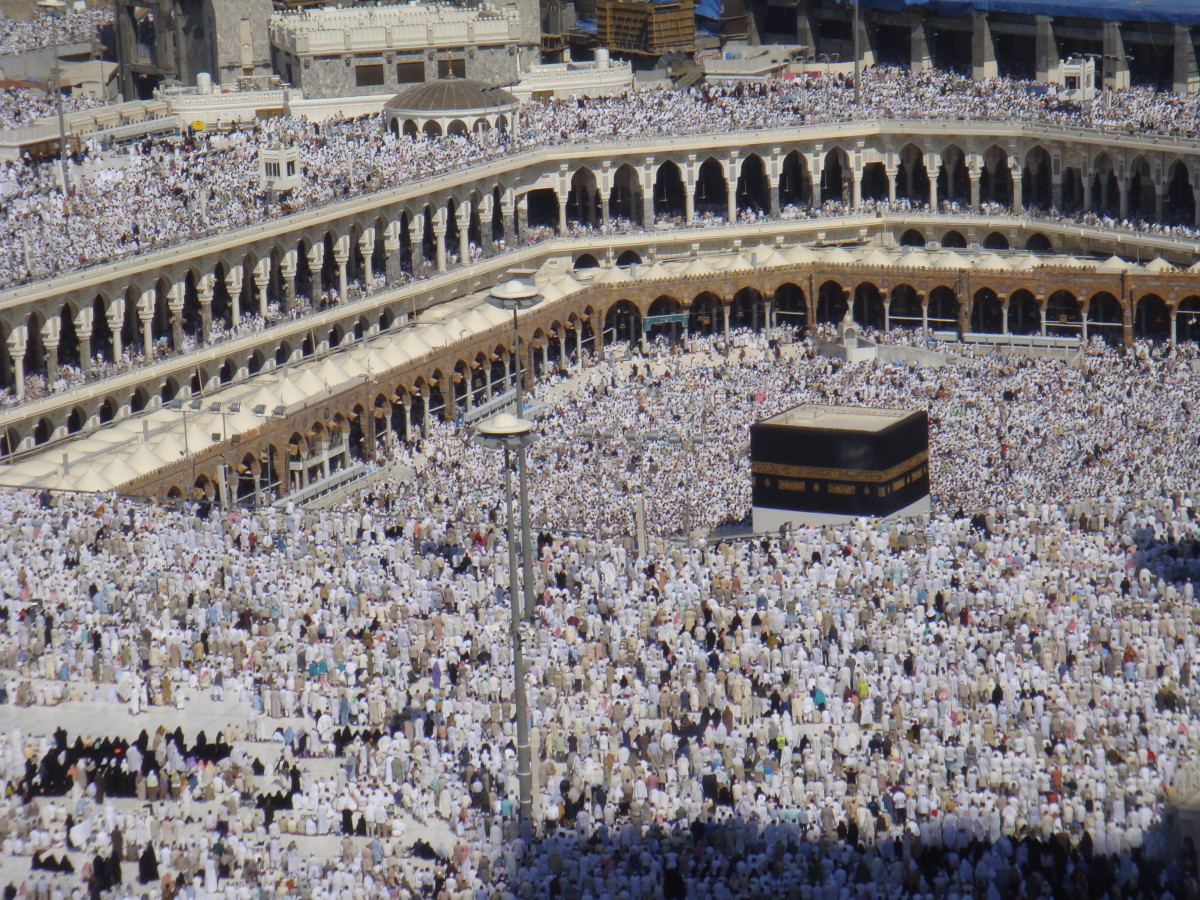

The Hajj exhibition, which opened at the end of January is an ambitious and impressive one, charting two millenia of the history of Mecca as a destination for pilgrims, even before Mohammed. Processions across North Africa in the Middle Ages, present day pilgrims jetting in from across the world in their millions, the rituals around the sacred Ka’ba, the cube at the centre of the Grand Mosque, all work into a grand narrative, well-told as one would expect from the British Museum, home to Britain’s national collection of antiquities. It is soul-stirring stuff.

But the omissions from the exhibition tell another story. The Hajj exhibition is utterly lacking in contention, quite a feat since at its heart lies Saudi Arabia and Islam.

Aside from the siege, even more predictable tragedies have been pushed aside. Death in numbers is a regular feature of the Hajj. Every few years, walkways collapse from the sheer number of people, and pilgrims are crushed. Stampedes claim hundreds of lives—a stampede in a tunnel in 1990 killed 1,426 people. Fires have broken out in the tented village in nearby Mina, where pilgrims sleep overnight for the stoning ritual. In 1997 70,000 tents went up in flames, and three hundred died. Despite extensive vaccination requirements, the confluence of so many people from across the globe makes the spread of infectious diseases another hazard. They receive a mention in the catalogue, in an essay by scholar Ziauddin Sardar, but not in the halls of the show.

Putting together the Hajj exhibition involved much diplomacy. The items in it were drawn from collections across the world, but getting Saudi Arabia to cooperate was key. Neil MacGregor and the curator Venetia Porter visited the kingdom in 2009 where they met with Prince Sultan bin Salman, Prince Faisal bin Abdullah, and Princess Adelah bin Abdullah. It was agreed that the King Abdulaziz Public Library, founded by the current ruler of Saudi Arabia as part of a project to establish Saudi heritage, would become the partner to the event. HSBC Amanah, the branch of the bank that provides shariah-compliant loans, offered sponsorship.

Despite warm thanks for their support from both MacGregor and Porter on the opening of the exhibition, getting to that point was not easy. Saudi officials were wary of what potentially could go wrong. In December, a month before it opened the final shipment of exhibits had yet to arrive and, according the Economist, there was a chance the show wouldn’t go ahead. One person associated with the show, who asked not to be named, suggested to me that the Saudis held the cards when it came to how the exhibition was staged.

The British Museum maintains the exhibition was entirely under its own control, and disputes the idea the show was held in the balance by the shipment. “The selection of all the objects in the exhibition and the decisions on structure and themes was made entirely by the BM curators,” says their spokesman. “The Saudi authorities never questioned the choice of objects.”

However, for a country tetchy about its image abroad, the Saudis enjoyed this spotlight. The opening was attended by a clutch of British royals, many of whom double up in government roles, as well as our own Prince Charles. The Hajj is one of the few openings into the closed kingdom, and Saudi dominion over Mecca is not without controversy. ”The Hajj is a very important use of soft power,” says Dr Mai Yamani, the Saudi scholar. “The Saudis have spent a lot of money on it, to create a form of legitimacy in the Muslim world. When King Fahd adopted the title of Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques, that was partly a response to the threat of the Islamic revolution and Khomeini questioning why the al Saud’s were the rulers of it of it.”

As the river of black gold runs dry and the Hajj continues to grow, it is not unthinkable that it will become the country’s greatest financial asset.

The exhibition is something of a showcase of achievements. Among the exhibits is a maquette of the new mosque expansion due for completion in two years time which will see it enlarged to accommodate another 1.2 million worshippers. Over the last forty years, the holy sites have gone through cycles of rebuilding to try to absorb the ever-growing flood of pilgrims. Issuing visas, accommodating in Mecca, shepherding from place to place, and providing the space for worship for over 2 ½ million people in one week makes the 2012 London Olympics preparations look like a village fete by comparison. For the stoning of the devil ritual, every pilgrim collects 49 pebbles on the plains of Muzdalifah, then carries them to the Jamarat, originally pillars, now three huge walls. Consider the logistics of that. What used to a bridge for the pilgrims is now being redeveloped in a twelve-story building. The old Ottoman parts of the Mosque are being replaced by multi-level praying halls.

This is worship on an industrial scale, and the Saudis, particularly the King as Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques, performs it as part of a duty. The mosque expansion is due to cost $10 billion.

But there is another way of looking at this. In 1924, the Abdulaziz bin Saud tribe, which had been conquering swathes of what is now Saudi Arabia, had their £5,000 (about $7820) annual grant from the British government withdrawn. Six months later, they set their sights on the capture of Mecca, then ruled by the Hashemite King Hussein. Territorial expansion was one incentive, the other was that the city’s cash cow – the pilgrim tax then levied on the 20,000 visitors, was handy for the then-slim al Saud purse. When Hussein abdicated his way out of the al-Saud conquest crisis, he left his kingdom with £800,000 (about $1.25 million) in his suitcase, 15 years worth of the tax. The exhibition notes that the al-Sauds dropped the local levies when they assumed control of the holy site. Other accounts record that local tax payable became a state tax with wealth dispersed across the kingdom.

The Hajj visa may now be free, but the pilgrimage is not. The accredited tour companies who run the Hajj offer packages with names like “VIP super deluxe.” The economy package comes in at around £2,500 from the UK but for £6,500 one can be accommodated in the top hotels, have VIP European-style tents at Mina, goodie bags and fully qualified Sheikhs as guides. Incidentally, the British Museum hosted a Hajj tour operators exhibition earlier this month.

It may not sit easily in an exhibition about the spiritual aspects of Islam, but business is part of the Hajj. One of the prayers said by pilgrims is, “God make this a blessed hajj and a successful business”. Long a market place for pilgrims, bringing carpets and gemstones from across the world, Mecca has transformed over recent years. The city boasts 5 star hotels and shopping malls. Casting its shadow over the Mosque is the just-completed Clock Royal Tower Hotel, the world’s second tallest building after the Burj in Dubai, which has a replica of Big Ben atop it.

Gulf News has estimated that the Hajj and the Umrah, the lesser pilgrimage that can be conducted at any time of year, contributes $30 billion to the economy, through the provision of accommodation, travel services, even animals for slaughter. That is 6 percent of the Saudi’s total GDP—with oil revenues stripped out, it’s more like 15 percent.

Saudi Arabia’s status as patron has been repaid magnificently. As the river of black gold runs dry and the Hajj continues to grow, it is not unthinkable that it will become the country’s greatest financial asset.

The fate of old Mecca doesn’t merit a mention in this exhbition. Until 50 years ago it was thronging with 7th century buildings. These have been largely demolished, including the houses of the Prophet Mohammed, his first wife Khadijh and Caliph Abu Bakar, father of another of the Prophet’s wives. Only a handful of historic buildings remain and even they are under threat.

Such cultural vandalism is authorized by Wahhabism, the particular strain of Islam the Saudis follow. In their interpretation of the Quran, the worship of gravestones is proscribed, and so too anything old and venerable. “Conservation Saudi-style is out of step with almost the entire Muslim world,” says Sadakt Kadri in his new book Heaven on Earth. “The Sphinx still gazes contemplatively from Giza; the pre-Islamic cities of Palmyra and Persepolis survive replete with graven images in the deserts of Syria and Iran; and domed shrines are part of the municipal furniture in cities from Istanbul to Agra. Only the Taliban have displayed a similar aesthetic, when they restored two ancient sandstone statues of the Buddha to oblivion with rocket launchers in March 2001”.

For the British Museum, the preservers of cultural history, to fail to mention the fate of Mecca seems at best negligent. Put with the other omissions, the exhibition at times has the gloss of an advertising brochure.

In the final room of the Hajj exhibition, set alongside reflections from everyday pilgrims of their experience of Mecca, are a handful of quotes from globally worshipped superstars, Mohammed Ali and Yusuf Islam among them. This quotation from Islam, formerly Cat Stevens, about his first Hajj in 1980, is printed in large fonts on the wall.

“I had at last found that dimension where human existence ceases to be held by the gravitation of sensual and worldly desires, where the soul is freed in an atmosphere of obedience and peaceful submission to the Divine Presence.”

The observer could not leave the exhibition without wondering whether all the omissions amounted to another form of submission.