People have been awkward at least since the middle of the fourteenth century, when the word was coined in English. It means “moving in the wrong direction” (like “northward,” but awk + ward), zigging when a zag is in order. Even the spelling of “awkward” is awkward if you stare at the “k” sandwiched between two “w’s.”

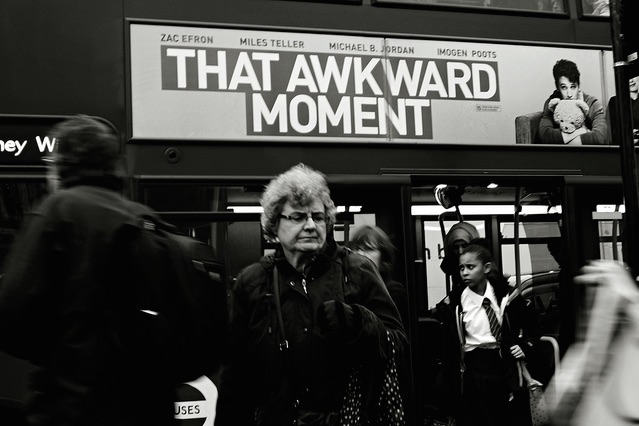

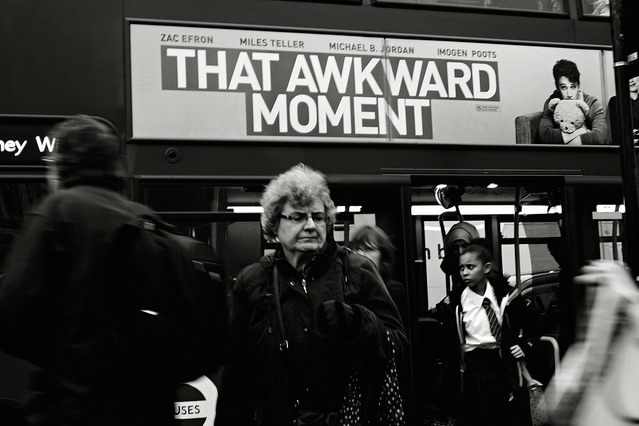

Awkwardness is to be avoided at all costs, and people will go to great lengths to be sure that their interpersonal encounters contain as little awkwardness as possible. (This is why breaking up via text message is such a useful innovation; it lets you skirt that twitchy moment of definitive separation.) At the same time, awkwardness is one of the most turned-to sources for entertainment, inside or outside the media; there is something delightfully painful about witnessing awkward scenes. In his book Awkwardness, Adam Kotsko takes a celebratory position toward the phenomenon, tracing its history and philosophical underpinnings in Western culture and identifying its function in popular cinema and television. While it is nice to see someone embrace the concept as potentially productive for the human psyche, I want to think through its ubiquity in America, and piece together the possible repercussions for a populace that simultaneously avoids and steeps itself in this kind of social discomfort.

It’s not that there are suddenly throngs of awkward, creepy people everywhere; it’s that we know less and less how to deal with even the most basic negotiations necessary for face-to-face interaction.

A sharp student of mine named Gabriella has a compelling theory about awkwardness. She says that when a person describes another as awkward—or that other favorite buzzword today, “creepy”—it only means that the accuser is unable to manage the social situation at hand. It’s not that there are suddenly throngs of awkward, creepy people everywhere; it’s that we know less and less how to deal with even the most basic negotiations necessary for face-to-face interaction. Circumstances that twenty years ago would have been viewed as coming with the territory of talking to another human being are now considered “awkward” or “weird” or “uncomfortable.” Anything that doesn’t cleanly fit into a pre-scripted expressive category is automatically regarded with suspicion.

There are some interesting synonyms for “awkward,” but they never quite do justice to the all-encompassing concept: inept, bungling, clumsy, unskillful, heavy-handed, tactless, undiplomatic, inconsiderate, incompetent, klutzy, inelegant, unsophisticated, cumbersome, unwieldy, ungainly, graceless, blundering, gawky. I like the expressions “all thumbs,” “butterfingered,” and especially “ham-fisted.” Some of these terms describe a person; others, an action. But “awkward” is the best catchall word to describe an individual, a circumstance, a sentence, or even the uncomely fit of a piece of clothing.

“Awkward” is sometimes difficult to translate into other languages. In French, you have maladroit and gauche (which means “left”), both of which have made their way into English. The latter hints at a kind of social incompetence while the former seems to imply a lack of physical proficiency. To describe an awkward conversation, the French use the adjective délicat or maybe gênant (embarrassing). In Italian, you have words like goffo, impacciato, and sgraziato, which all imply a physical clumsiness or lack of grace. To describe an awkward phase, like adolescence, Italians use words such as problematico, difficile, or complicato, whose equivalents in English don’t get anywhere near the efficient beauty of “awkward.” In Spanish, there’s torpe, which shares an etymological root with the English “torpor” and implies numbness, or desmañado, which suggests that the person is not good with his hands. In German, an object that is unhandlich is not easily handled. There’s also ungeschickt (which refers to the fact that fate, das Geschick, doesn’t come to your aid), unbeholfen (that you can’t be helped), linkisch (“leftish,” like gauche in French, as in having two left feet), and tölpelhaft (like a clumsy sea bird). My favorite is tollpatschig, a word borrowed from the Hungarian word for foot soldier. Apparently, Hungarian foot soldiers in the seventeenth century often had no shoes, so they strapped soles directly to their feet with strings, which made them walk in a funny way. Austrians were the first to use this as a derogatory term to describe a clumsy person. It’s notable that in English and other languages, the feet and hands are so important to the concept of awkwardness. These appendages can be the biggest nuisance in the management of one’s environment. Hands and feet, the body’s tools for doing and for going, are often the primary impediments to physical competence. The faux pas, or false step, brings about the social tumble.

The limbs and tongue compete to embarrass the person who owns them. In Italy once, I meant to order an espresso and a croissant (un cornetto), but instead ordered an espresso and a man whose wife sleeps around (un cornuto). In high school and later, I attended many of my brother’s heavy metal shows—he is a drummer, the kind who breaks sticks and obliterates drumheads—which caused, I believe, some hearing loss. For this reason, I am always speaking too quietly or too loudly, and I have to ask people to repeat what they’ve already said multiple times. Furthermore, I move according to the laws of vaudeville. I run into things. I forget the dimensions of my body and bump into easily avoidable, breakable obstacles. My three-dimensional vision is deficient: I notice this most when trying to parallel park, never sure at all of the size of my vehicle even though it sits plainly around me. The car balloons into a massive object or shrinks to miniature proportions when I look at its contours through the rearview mirror, but it never seems to me the size it actually is.

I often daydream about falling down in front of large crowds of people, usually walking toward the podium at an important conference in front of illustrious colleagues and biting the dust as hard as one possibly can.

I’ve been told by friends and acquaintances that my walk is ridiculous. I have a sort of bouncing, elastic gait to my step even when moving slowly. Some say I move belly first in a weird kind of slouch. Others have noticed I have a hard time moving in straight lines. Some claim I drag my heels. Still others have identified an awkward smoothness in the way I still roll my feet as I learned to do in marching band. How can a person bounce, slouch, swerve, drag, and roll all at the same time? I don’t know, but that’s the only way I know how to describe my walk. My boyfriend calls me “gazelle.”

The moment my walk is called to my attention, I become hyper self-conscious about it. My gait changes instantly. I have yet to catch a pure sample of myself walking; as soon as I pay attention to my walk, it becomes something very different from what it was. I had a professor once who walked like a slow-moving waterbird, the stately and long-legged kind, like a flamingo or a heron. Her gait was quicker, but the mechanics were definitely avian and of the aquatic variety. You could identify her in a crowd from three acres away by her strutting head. A friend of mine claims she can recognize everyone she knows based solely on the sound of their steps. Each person is marked by a singular peripatetic cadence: swish-clop-swish, scuff-scuff-scuff, tip- tap-tip-tap. The rhythm of one’s feet is a kind of identity metronome.

The French philosopher Henri Bergson had a theory about why we laugh about tripping and other such forms of awkwardness. He argued that when people are too trapped in the automaticity of their mechanical movements and when these are insufficient in dealing with the environment at hand, a comical situation presents itself. Bound by the habits of movement, people sometimes forget to adjust for new terrain or unexpected obstacles, or they get so accustomed to their standard environment, they expect the body to do all the work intuitively. I often daydream about falling down in front of large crowds of people, usually walking toward the podium at an important conference in front of illustrious colleagues and biting the dust as hard as one possibly can, grabbing at whatever is closest to keep from falling, which happens to be the sleeve of the tweed blazer of a renowned specialist of twentieth-century French literature, which rips emphatically in the silence of the startled conference hall. Or I jolt the table in front of the panelists waiting to give their talks and spill Dasani on their crotches. In some versions, my shoe flies in an unnatural direction, as if my fall caused physics to undo itself momentarily. Or I knock out my front teeth on the lectern. I’ve mentally rehearsed all the possible scenarios of this second Fall of Woman.

Tripping is the great equalizer. When you are intimidated by someone, it is helpful to imagine either what this person was like when they were seven years old or what they look like when they lose their footing on the stairs. Either way, the hidden vulnerabilities of the intimidating individual are exposed, making them human and fallible like everyone else. The fact that we all can fall creates proximity between the most disparate types of people. It works like the allegorical danse macabre frescoes painted on the walls of medieval churches, which show death in a dance with people of all social ranks, a depiction of death’s universality. Tripping is like death; not one of us is exempt from it.

An interesting if little-known fact: the etymological origin of the word “scandal” means a trap or a stumbling block intended to hinder an enemy. The scandal is that which trips up one’s social life. The awkwardness of political scandals, especially those of a sexual nature, comes from the public visibility of the secret part of someone’s life. When the private becomes public, awkwardness is always a possibility.

Intimate life is generally carried out with the understanding that there is no audience (outside the intended one) to bear witness to the confidential palette of one’s desires. When this expectation is frustrated by public exposure, the reflex is to cover up quickly. But this is a hopeless impulse. Once the image of someone’s tweeted junk is flashed before the public, it is etched with an acid quill on the surface of the brain. Like the blood on the hands of Lady Macbeth, the picture is indelible even once the tangible object is no longer visible. Such awkwardnesses cannot be effaced. I predict that the threat of blackmail will be much less effective in the not-so-distant future, since people will be more and more aware that their own digital goings-on have the potential to be hacked and exposed. The thrill of seeing it happen to someone else will decrease with this knowledge. Someone else’s exposure will make you think increasingly of your own exposure and thus the revelation of naughtiness will lose its appeal as a source of entertainment. The power of this kind of blackmailing will dwindle since an indecorous picture will no longer trigger public indignation.

In Milan Kundera’s The Art of the Novel, in a chapter called “Sixty-three Words,” Kundera writes an entry on the word “obscenity,” noting the difficulty of seducing a woman with obscene words in a language that isn’t your own. If you’ve had lovers who didn’t have a strong command of your language but tried to seduce you with it anyway, you understand this farcical scenario, which turns the flushed skin of passion into the flushed skin of embarrassment. Sex has a highly systematized vocabulary and grammar. While the foreign accent can triple or sextuple a person’s appeal, the misuse of a preposition can cause the whole thing to come crashing down. Using an idiomatic expression that doesn’t exist in the target language—“I want to butter your biscuits”—induces more laughter than desire.

Italo Calvino’s Mr. Palomar chisels out a long shoreline of awkwardness. The protagonist is out of sync with the world, fumbling at life because of his tendency to overthink. In a chapter called “The Naked Bosom,” Mr. Palomar comes across a topless sunbather on the beach. Confronted with the non-neutral fullness of the female form, he deliberates how he should behave in this encounter. Should he ignore her, as if she were part of the scenery? Should he “create a kind of mental brassière” to keep his eyes from grazing her breasts? Or should he acknowledge that her body is beautiful by looking at it unambiguously, as one would a flower?

He vacillates, pacing and wondering what to do, which disturbs the woman, causing her to pack up her things quickly and leave, “as if she were avoiding the tiresome insistence of a satyr.” This is only one of his countless indiscretions. When in the company of others, he has purposely developed the habit of biting his tongue three times before saying anything, to avoid saying something stupid.

Palomar is an observer; he walks through the world noticing in particular those elements of life that are slightly off-kilter, like himself. He loves to watch giraffes race at the zoo, admiring their “unharmonious movements”: “The giraffe seems a mechanism constructed by putting together pieces from heterogeneous machines, though it functions perfectly all the same.” He watches the clumsy mating ritual of two tortoises who fumble at love, making it impossible for an outside observer to tell if their lurching and slow acrobatics were the picture of successfully choreographed coitus. Palomar even turns stargazing into an awkward affair through overpreparedness, as he arms himself with star maps, a flashlight, and a deck chair. He suddenly realizes that in the dark—as he’s been craning his neck, twisting and turning in his chair, fooling with his stubborn charts—he has transformed himself into a spectacle more interesting than the sidereal show above. A small crowd has gathered around him in the dimness, “observing his movements like the convulsions of a madman.” Palomar is representative of our time because he is self-aware to the point of immobilizing himself. Too busy scrutinizing his every thought and action, trying to analyze and prepare himself for every possible scenario, he never does what comes naturally.

There is something delightfully painful about witnessing awkward scenes.

Over one hundred years earlier, Emerson took a different stance on the question of awkwardness. For him, its cause is too little thought. He wrote this beautiful passage in an essay called “Social Aims”:

Nature is the best posture-master. An awkward man is graceful when asleep, or when hard at work, or agreeably amused. The attitudes of children are gentle, persuasive, royal, in their games and in their house-talk and in the street, before they have learned to cringe. ’Tis impossible but thought disposes the limbs and the walk, and is masterly or secondary. No art can contravene it or conceal it. Give me a thought, and my hands and legs and voice and face will all go right. And we are awkward for want of thought. The inspiration is scanty, and does not arrive at the extremities.

At first, Emerson seems to put nature at odds with thought, since he claims that the sleeping man, in his unpondered and innate bearing, displays no awkwardness. Children, who have not yet “learned to cringe”—what a thought!—are as natural and perfectly postured as the man in slumber. Cringeworthiness is a meaningless concept to a child. But in his last sentences, we see that thought is somehow an extension of nature, a rectifying force. While Palomar is awkward in his surplus of thought, for Emerson, “we are awkward for want of thought.” And here, once again, the problem of the extremities presents itself. Heady inspiration has trouble trickling down into the arms and legs. There isn’t enough thought to go around. So while nature is the posture-master, the human, largely cut off from nature, relies on the brain to calibrate posture. Consciousness can program the body to move fluently. But only in sleep can we return to the fully unprogrammed, graceful state reserved for children, poplar trees, and herons.

There is something unbearable about witnessing scenarios that have moved inextricably deep into the awkward zone. It makes you want to run away. And when you can’t run away, you show your discomfort visibly, which is why words like “facepalm” and “cringeworthy” have gained a lot of currency in recent years. Interestingly, for a moment to be cringeworthy, it requires you to temporarily put yourself in the place of the person who has committed the sin of awkwardness; it is an empathic response. You imagine yourself to be that guy who wanted to give a high five but was snubbed, his hand suspended dumbly in midair with no hand to answer it. Or that pageant contestant who answers a question about world affairs of grave importance with prettily spoken nonsense: you cringe at her brainlessness but you secretly know that if you were onstage in heels with lights in your face and pressure weighing on you to be perfect, all this fueled by a lifetime of weirdness that would put you on a pageant stage in the first place, you would likely have a difficult time producing a clever response. We cringe because we project ourselves into the scene, making ourselves a character in the drama of the uncomfortable. The person who made the error cringes, as do the witnesses to this error. In this mystical way, awkwardness engenders a community of the embarrassed. We recognize each other by our red faces.

What are we to make of this ubiquity of awkwardness, in all its various degrees and settings? Is it the expression of a general sense of alienation? You can’t really assume any longer that the person sitting next to you was brought up in a similar way, shares your political views, or even speaks your language. Our social intuition is out of joint because the clusters of individual experiences brought to the table are decreasingly similar. Everyone now has the potential to be odd in the eyes of someone else.

America is a muddle of influences. In the 1950s, there was perhaps some standard of social behavior that worked as a code of conduct. Manners were established at home, where both parents were often present, or through church or school. Many people had more contact with others outside their own age group: sometimes three or perhaps even four generations lived under the same roof, which meant that the values of the grandparents were more easily transmitted to the grandchildren. People are now cloistered by age. Back then, the middle class was pretty big. Races mixed less; classes mixed less. There were fewer newly arrived foreigners, or at least there were foreigners from fewer places. People were trained by the historical inertia of cultural habit. All of this has changed, I think for the better. While at times it may feel destabilizing not to have a clear code of conduct in the social world, everyone is basically in the same boat. What a unifying feeling that we are all equally lost!

My point is that awkwardness comes with the territory of diversity. I don’t mean racial diversity or even cultural diversity, but rather, more comprehensively, the very basic diversity brought about by being a different human from someone else, that is to say, the atomization of the collective into individuals. This has been one of the principal projects of America: to elevate the individual above all other units. But at what cost? Awkwardness is the outcome of not knowing how to deal with an unfamiliar (i.e., foreign) situation. We are becoming increasingly alien to one another by virtue of the mediated existences we lead. By making everything outside the body more and more foreign, more and more remote, we cause the occasions for awkwardness to increase exponentially. Any encounter contains within it this risk. Awkwardness is about feeling out of control and incapable of maneuvering things back to a manageable state. It is produced by the anticipatory anxiety of knowing that whatever comes from outside threatens the equilibrium of the closed self.

While awkwardness is entertaining at times, it bespeaks an unnecessary anxiousness in the face of the unknown and the unknowable. Feeling ill at ease is not the only possible response to a situation in which you don’t know what to do. The next time you find yourself in an awkward circumstance, imagine if you embraced fully the foreignness of the moment. You are no longer intimidated that you’ve never encountered this kind of moment before. You are aware of but not oversensitive to the unclearness of your role in the situation. You watch it as a detached observer. Recognize it as an occasion for thinking beyond yourself, outside your body and your routine. Be and love the alien. Can the uncanny. Realize that when it’s over, it constitutes part of your broadened repertoire of experience. Remember: the “awk” in “awkward” is a fictional direction. Just assert yourself calmly in the flow of the unknown. When every possible direction is interesting, there is no such thing as waywardness.

Christy Wampole is an assistant professor of French at Princeton University. Her research focuses primarily on twentieth- and twenty-first-century French and Italian literature and thought.

Adapted with permission from The Other Serious: Essays for the New American Generation by Christy Wampole. Copyright (C) 2015 by Christy Wampole. Reprinted by permission of Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.