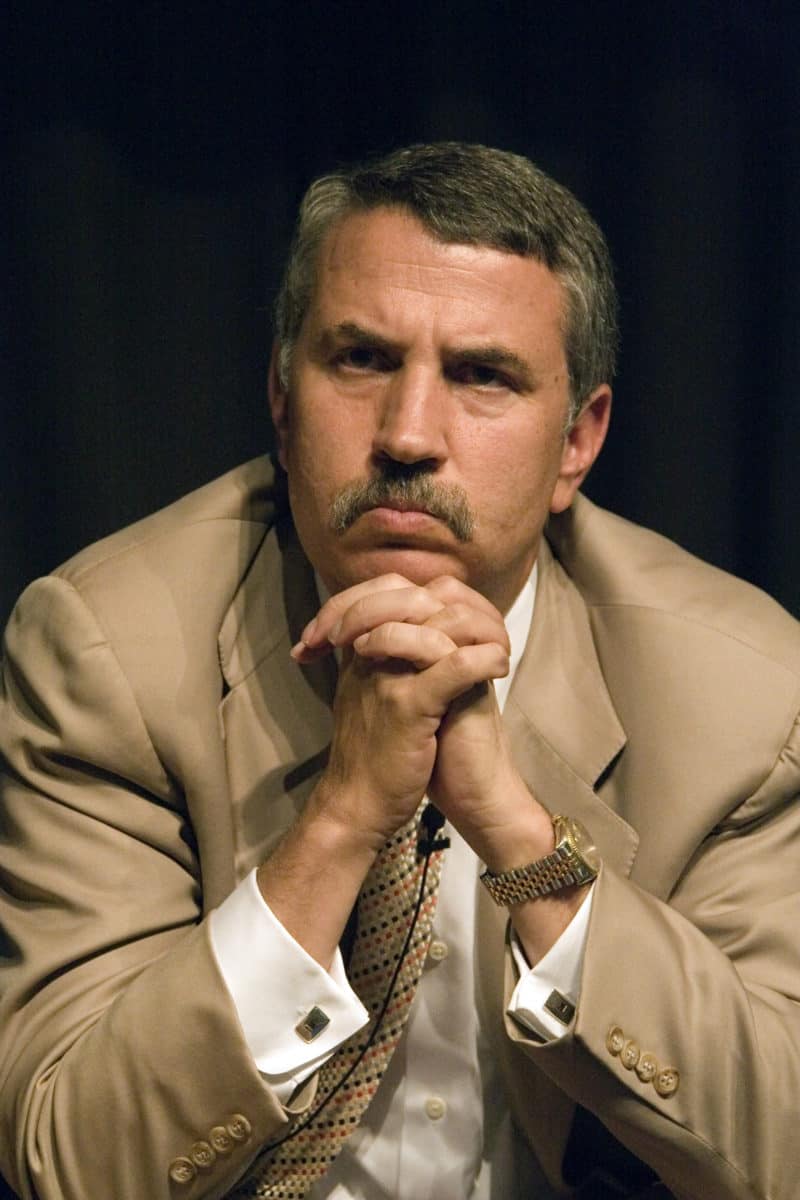

The Imperial Messenger: Thomas Friedman at Work is a take-down of the three-time Pulitzer recipient and foreign affairs columnist for the New York Times. One of the primary establishment cheerleaders for the war on Iraq, Friedman is known for such moves as instructing the entire Iraqi nation to “Suck. On. This” in response to 9/11 despite himself condemning the Bush administration for suggesting a link between Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden. He meanwhile urges the U.S. public to believe that the invasion is “the most radical-liberal revolutionary war the U.S. has ever launched” while simultaneously defining himself as “a liberal on every issue other than this war.”

The following excerpt appears in Section I of the book, “America,” shortly after a discussion of Friedman’s 2002 stipulation that war-based democracy installation in Iraq is “the most important task worth doing and worth debating.” He admits that it “would be a huge, long, costly task—if it is doable at all, and I am not embarrassed to say that I don’t know if it is.” The excerpt covers some of the complications that arise when foreign affairs columnists are not required to maintain a coherent discourse. All quotes and figures are properly cited in the work itself.

—Belén Fernández

Recent years have seen a surge in Friedman’s insistence on the need for “nation-building at home,“ in order to resolve issues ranging from the United States’s “mounting education deficit, energy deficit, budget deficit, health care deficit and ambition deficit” to Penn Station’s “disgusting track-side platforms [that] apparently have not been cleaned since World War II” to the fact that, while China spent the post-9/11 period enhancing its national infrastructure in preparation for the Beijing Olympics, “we’ve been building better metal detectors, armored Humvees and pilotless drones.” Friedman’s fury over funding cuts to the National Science Foundation might be more understandable, however, had:

1. The NSF appeared somewhere on the 2002 hierarchy of most-important-even-if-impossible-tasks.

2. He specified that the Iraq war be fought without Humvees.

3. He not advised Democratic presidential candidate John Kerry in 2004 to “connect up with that gut fear in the American soul and pass a simple threshold test: ’Does this man understand that we have real enemies?’“ by “drop[ping] everything else—health care, deficits and middle-class tax cuts—and focus[ing] on this issue.

Everything else is secondary.”

Consider for a moment that over half of U.S. government spending goes to the military, an institution Friedman lauds as the protector of American economic hegemony in The Lexus and the Olive Tree:

“Indeed, McDonald’s cannot flourish without McDonnell Douglas, the designer of the U.S. Air Force F-15. And the hidden fist that keeps the world safe for Silicon Valley’s technologies to flourish is called the U.S. Army, Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps. And these fighting forces and institutions are paid for by American tax- payer dollars.”

Consider, then, the 2007 estimate by the American Friends Service Committee that the hidden fist’s not-so-hidden maneuverings in Iraq were costing $720 million a day. The Washington Post reports that this sum alone “could buy homes for almost 6,500 families or health care for 423,529 children, or could outfit 1.27 million homes with renewable electricity,” as well as making substantial contributions to the U.S. education system, which Friedman has categorized as one of the many areas in which the country “has been swimming buck naked.”

This is not to imply, of course, that had these funds not been used on war they would have been used on these specific domestic nation-building projects, but rather to point out the sort of self-contradictions one invites by maintaining unwavering commitment to few principles aside from the idea that America should dominate the world.

Despite Friedman’s newfound annoyance that the United States is preoccupied with nation-building abroad and that “the Cheneyites want to make fighting Al Qaeda our Sputnik“ while “China is doing moon shots“ and turning from red to green, he credits the U.S. army with “outgreening al-Qaeda” in Iraq. In Hot, Flat, and Crowded, we learn that this has been achieved via a combination of insulation foam and renewable energy sources, reducing the amount of fuel required to air condition troop accommodations in certain locations.

After speaking with army energy consultant Dan Nolan— whom he “couldn’t help but ask, ’Is anybody in the military saying, “Oh gosh, poor Dan has gone green—has he gone girly-man on us now?“ ’—Friedman announces that the outgreening of Al Qaeda constitutes a typical example:

“of what happens when you try to solve a problem by outgreening the competition—you buy one and you get four free. In Nolan’s case, you save lives by getting [fuel transportation] convoys off the road, save money by lowering fuel costs [from the quoted ‘hundreds of dollars per gallon’ often required to cover delivery], and maybe have some power left over to give the local mosque’s imam so his community might even toss a flower at you one day, rather than a grenade.”

The fourth benefit, courtesy of Nolan, is that soldiers will be so inspired by green efforts at their bases in Iraq that they will “come back to America and demand the same thing for their community or from their factory,“ which Friedman reports as unquestioningly as he does the allegation that the U.S. army prompted the desegregation of America by “show[ing] blacks and whites that they could work together.” As for the first three benefits gotten for “free” with the Al Qaeda outgreening purchase, it should be recalled that the very appearance of Al Qaeda in Iraq was itself no more than a free benefit of the U.S. invasion, as were convoy fatalities, heightened fuel costs for the U.S. military, and grenades. A deal indeed.

It is no less than remarkable that, in a matter of six pages in a book purporting to serve as an environmental wakeup call, Friedman has managed to greenwash the institution that holds the distinction of being the top polluter in the world. The feat is especially noteworthy given that, smatterings of insulation foam and solar panels notwithstanding, the U.S. military’s overwhelming reliance on fuel means that its presence in Iraq is not at all reconcilable with Friedman’s insistence that dependence on foreign oil reserves is one of the greatest threats to U.S. security. The greenwashing incidentally also occurs after Friedman has decreed that the United States should cease operations in Iraq so as not to “throw more good lives after good lives.“

In 2010 it is then revealed that certain branches of the armed forces are strategizing to outgreen not only Al Qaeda but also the Taliban and the world’s petro-dictators. Friedman exults over the existence of aviation biofuel made from pressed mustard seeds and the existence of a green forward-operating Marine base in Helmand Province, Afghanistan, offering encouragement such as “Go Navy!“ and “God bless them: ’The Few. The Proud. The Green.’ Semper Fi.“ It is not clear whether Friedman has forgotten that he is vehemently opposed to the military escalation in Afghanistan.

This excerpt is from The Imperial Messenger: Thomas Friedman at Work

Copyright © Belén Fernández 2011

Published by Verso Books

Reprinted here with permission.