The premier of NBC’s The Playboy Club, which aired on September 19th, opened with a bang as blood vessels popped in the brains of feminists across the nation. There might be one, over a month later, still lying in the ethereal glow of her television screen, catatonic—in a state of kernal panic brought on by system inputs that didn’t add up. By the time the show’s second and third episodes aired, the switchboard of American thought was blinking furiously. Articles had spread across the Internet expressing the outrage, compassion, and even gratitude for a new version of the Playboy narrative. And also, for a new version of Hugh Hefner. Even though by now the dust stirred by the show has settled back down on our memories of Playboy’s heyday, there is something curious about our reactions to it. Beneath the inevitably evocative subject matter in the Playboy Club, something even more interesting bubbled and almost spilled over. And that is, how aggressively we’d like to bury Hugh Hefner’s contributions to second-wave feminism.

The Playboy Club show was canceled, if you haven’t heard. Not because the Parents Television Council denounced it, or because Gloria Steinem spoke out on its poor taste; but that certainly didn’t hurt. No, it was probably just that the numbers weren’t adding up—Nielson ratings indicate that the show started with just over 5 million viewers and dropped to just over 3 million viewers by the third episode. Compare those numbers to say, NCIS on September 5th, (9.5 million viewers) and you start to get the picture. Some people said that no one really had any hope for the show. Others said the show wasn’t really about Playboy, so PTC could denounce away. But can you make a high-budget show called The Playboy Club and expect no one to watch it and no one to associate it with porn? For no one to associate porn with anti-feminism? The thing is, the feminist movement was exploding at the same time the show was supposed to take place. Not a political plot? Silly rabbits.

Under the spotlight in the ultra modern Playboy Club, Chicago circa 1960, bunny Carol-Lynne finishes her number and bounds offstage to the waiting arms of her dapper don, Nick Dalton. Dalton, the club’s key-holder and lawyer, is just back from winning a case where his two “victims” were awarded monetary damages to the tune of 50 thousand a piece. He relays the news to Carol-Lynne who says, “Where do I sign up to be a victim?”

“You couldn’t be a victim if you tried,” replies Mr. Dalton as Carol-Lynne smiles, pearly teeth shimmering in the club’s diamond-studded semi-darkness. Oh, but she is trying to be a victim, our conservative values yell—just look at what she’s wearing! Yet the (probably accidental) double-entendre the show shoves through this repartee is: Bunnies are not victims; they’re not being objectified in their Bunny tuxedos, they’re being empowered. Bunny Carol-Lynne has Mr. Dalton, and every man, under her spell when she’s wearing her magic sexy suit. Hugh Hefner, it has been said, was empowering women by breaking the spell of puritanical sexuality in America.

At the time, Hef was progressive, aware, forward, and pro-women. He was even fixed up on a blind date with Gloria Steinem, as Levy recounts, before Steinem went undercover.

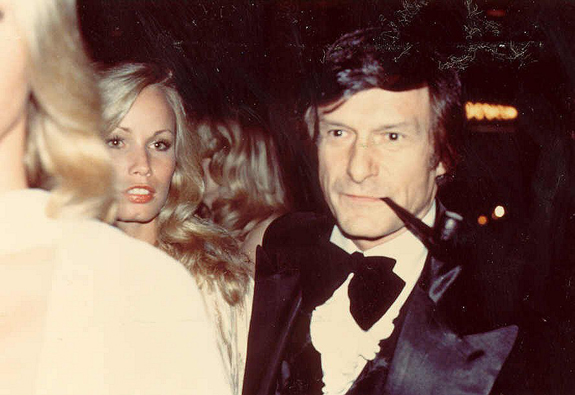

Hugh Hefner was once called a protofeminist and a social radical. But it’s been a while. Ever since Gloria Steinem put on a bunny-tard and tail for her undercover, investigative journalistic foray into the Playboy Mansion (resurfacing shocked and outraged), the world was hard pressed to see Hugh Hefner as anything but a lecher and Playboy as smut, if it didn’t already. But Hugh Hefner was not always regarded so conservatively. He went all-in for more than one controversial round of business roulette, backing (financially and ideologically) “The liberal political scientist Max Lerner, the sex education crusader Mary Calderone, Dick Gregory, Eugene McCarthy, Jesse Jackson, NOW,”as listed by People magazine in 1980. And in her examination of contemporary feminism: Female Chauvinist Pigs: the rise of raunch culture, Ariel Levy writes that “Roe and the legalization of the birth control pill—both of which were crucial to feminists—were both helped by funding from Hefner.” At the time, Hef was progressive, aware, forward, and pro-women. Levy writes that “a mutual friend even tried to set him up on a date with Gloria Steinem before she became famous. (It didn’t work out).”

But let’s be honest, was he pro-women or pro-sex? People decided for themselves pretty quickly back in the day. So while feminism broke off into factions of race, class, and geography in the 1970s, Hefner’s Playboy clubs, Playboy magazine, and the mansion lost almost all feminist cachet. Next to Steinem, Hefner now represents something like her opposite. According to People magazine, February 1985, Hefner was hurt that he had become the villain for feminists (even back then). “’Women are the major beneficiaries of getting rid of the hypocritical old notions about sex,’ says Hefner, who believes he played a large part in burying those notions. ‘Now some people are acting as if the sexual revolution was a male plot to get laid. One of the unintended by-products of the women’s movement is the association of the erotic impulse with wanting to hurt somebody.’”

And so when, in the first episode of the Playboy Club, Bunny Maureen buries her heel in the neck of a jilted suitor who is getting too frisky (sex appeal invoking violence?), we hear the apologist whisper from between the lines of the screenplay, “Ok, maybe he was wrong about some things,” says the voice. “But Hef meant well!” The voice whines. He never wanted women to get hurt, only to be sexually liberated. Though, I don’t think he promoted the idea of them being anything they wanted.

“The Bunnies were some of the only women in the world who could be anyone they wanted to be,” Hefner narrates in the same episode. This could easily be misinterpreted. What I gleaned from his sentence was that while she wore her Bunny suit, a Bunny could pretend her past didn’t exist; she could reinvent her identity each time she put on her bow-tie and tail. Women were given a chance to live in a Cinderella fairytale of male sexual appreciation, forever (or until midnight), like a prolonged Halloween. A forever Groundhog Day of Bunny dress-up. Yes, the Bunny did indeed see her shadow and it has been a long cold winter for women’s sexuality.

The Playboy Club wasn’t an apology for Hugh Hefner; and the nut of it was not a retelling of his story in a way that makes us see his historical contributions. If it’s in there, then it was accidental. But, there’s enough accidental apology to make us mad. Whether NBC admits it or not, the show is a Mad Men-era trend grab; a snatch at what’s been dubbed “retro-sexism;” the appeal of simpler values, and a juicily political moment, to boot. It just happened to peg the entire plot to an extremely controversial figure. The show’s creator Chad Hodge told the Hollywood Reporter, “I think there was a perception that we were trying to do something politically ambitious or make a statement or make this a show about empowering women, which sounds super boring to me… This is a fun, sexy soap.”

We are happy to embrace the Bettys and the Dons as they act out our history, but we’re not ready to see the Bunnies, and Hugh Hefner, express any aspect of women’s lib. We’re still figuring out how we feel about all that. This little television blip will probably be forgotten completely in a few more weeks—a little black mark on the timeline of feminism; an enemy submarine of ideology, blinking on the radar of America’s family values. Meanwhile maybe someone should make a show that narrates second-wave feminism, placing Bunnies in the appropriate hutch along the rainbow of advancements in equality. Hef could even be a character. Until then, the Bunnies will remain in between liberation and repression; living out whatever stigma we’ve attributed to them as they dance in their bunny costumes on the pages of history.