Win Tin, eighty-four years old when I met him, was a living legend not only in Myanmar but around the world. I was therefore a little timorous when I rang his phone number and explained who I was, but a wavering voice at the other end said graciously, “You may come to my house today at 5 p.m.”

To get there required a forty-minute taxi ride from downtown Yangon, out to the northeast of the city into a low-key suburban area, and a slow creep along several unmarked streets, searching for the place. The tarmac had crumbled at the edges of the dusty roads in which children ran riot. Wild greenery crept around the faded houses and threatened to turn the place back into jungle, and watermelon-red flowers splashed roadside bushes with color. When I finally found the house, a little girl answered the front door. She smiled broadly, revealing gappy teeth, and pointed behind me. I looked around and saw the tiny concrete cabin to the left of the leafy entrance gate, covered in ruby bougainvillea. I’d assumed this was where a security man might sit, or it could even have been an oversized kennel. But this was Win Tin’s home. He lived there alone. He couldn’t adjust to any other way. In his words, he had “no family life after spending almost twenty years in solitary confinement.”

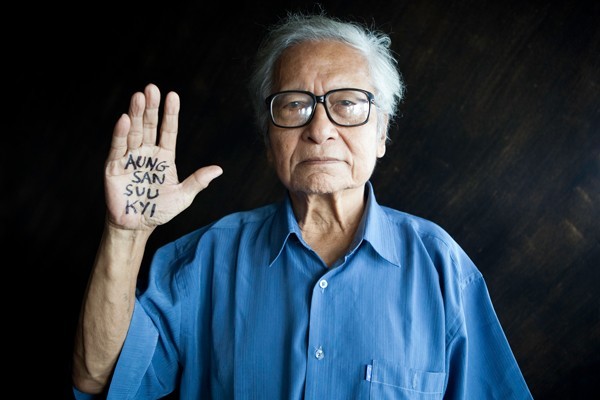

I knocked on the door and there he was, in the bright blue shirt he notoriously wore every day after his release, mirroring the uniform of the political prisoners who remain imprisoned, and whom he supported financially through the foundation he set up for the purpose. White-haired, bespectacled, and with twinkling eyes, he welcomed me in, apologizing that he was currently receiving a massage but that I could talk to him while it finished. A smiling younger man materialized, nodded at me, and sat down to pummel at Win Tin’s back while we spoke; it turns out the man was not a professional masseur but simply a pilgrim to his political hero, and he came to the cabin to provide massage for free four times a week.

I took a seat on one of the plastic chairs in the tiny living room and registered the décor. Spearmint walls, flaking slightly. An ancient, pale pink fan on an institutional table. A large, brightly colored painting of Aung San Suu Kyi on the wall opposite well-stacked bookshelves, and a faded, framed Amnesty International poster on the wall reading “Happy 75th Birthday Win Tin!” and showing that same face, only slightly less elderly, behind bars. Finally the great man came into the room and took his seat at the coffee table. The little girl darted in and brought us a thermos of tea, and we began to talk.

I asked after Win Tin’s health but he was not interested in that. Even though he had a pacemaker, chronic asthma, failing eyesight, back pain, and dental pain, among other health problems exacerbated by years of minimal medical care in jail, to his mind there were more important things to think about: his foundation, his work with the NLD as an elder adviser, the republication of his books, and ideas for the future. And despite all of that, for over three hours, in one evening, he regaled me in lucid prose with the story of his life, from his boyhood under Japanese and British rule, to his activism during a phase of fledgling independent democracy in the fifties when he set up an independent press council, to the arrival of the military junta, right through to the 1988 uprising, to his founding of the NLD party with Aung San Suu Kyi, and to his eventual imprisonment.

Very sadly, Win Tin died of organ failure while in hospital on April 21, 2014. Tens of thousands of people flocked to his home suburb in Yangon for a five-hour funeral in the roasting summer heat, many wearing blue shirts with his portrait printed on the front. Trucks rolled slowly behind the hearse, decorated with bouquets, wreaths, and red NLD flags at half-mast. According to The Irrawaddy, writer and NLD patron Tin Oo said in a eulogy that Win Tin’s death was “not only an immeasurable loss for the NLD but also for Burmese literature, national reconciliation, and the peace struggle.” The news magazine quoted one NLD member from the crowds as saying, “I came here to pay my respects…. For us, he is a symbol of courage. There is nobody else like him.”

Win Tin was not only the preeminent representative of the wrongs and the futility of Myanmar’s censorship regime, and a passionate advocate of freedom of expression, but he was a force of nature.

Win Tin’s Story

I was born in 1929, in a small town where my grandmother lived, but after only a few months I was brought back to Rangoon and I grew up there until the Japanese came in 1942. When the fighting between the Japanese and the British began a few years later, we moved back to my grandmother’s house to escape from it.

My parents were ordinary people, traders. But they were political, and I caught the political bug from them. My uncle, my mother’s brother, was a particular influence on me. He was one of the “thirty comrades” who went to Japan with Aung San [the founder of the modern Burmese army and the Communist Party of Burma], and he was Aung San’s personal assistant at the height of the resistance. I met Aung San back then, and I asked him if I should go for military service. He said I should not, because he had many followers who were keen to fight for him and had the ability to do so, but there were not enough who were educated. So he asked me to study instead. I took this seriously, so at university I studied hard.

I joined one of the university journals and trained myself, so that I could become a journalist and writer afterwards. I co-founded the Daily Mirror, which is still in circulation in Burma now. I wrote political comment articles on the economy, politics, and many things besides. If some people liked what I wrote and some didn’t, that was fine with me. It was quite normal back then.

In 1962 the military junta came to power. I managed to publish my articles about Eastern Europe in a book called A Moment in the Red World, but because of the liberal ideas it contained it was banned—it wasn’t published again until last year, fifty years later! That was the beginning of big changes for writers and journalists.

In 1967 and 1968, disputes escalated between us journalists and the government officers at the Ministry of Information. We asked for more press freedom, because we’d heard about the press freedom movement in Czechoslovakia against the Soviet regime. We put up similar suggestions to the minister, but myself and three other journalists were attacked as a result. In September 1988 we formed our party, the NLD, together with U Tin Oo.

They accused me of taking part in an uprising. There was no law I had broken, of course—this was a military tribunal and they didn’t go into details about the law.

I was first arrested and charged in 1989 for “helping outlaws.” The “outlaws” were two youth members of the NLD party who procured an abortion. I was accused of helping to hide them, which was not in fact true. At first I was sentenced to three years. But then, after about two years, I was summoned to the prison office. Speaking nicely and courteously, they asked me to sign a document to say I would never work in politics again after I came out. You are a journalist, they said, so you can write books instead. But of course I refused. Many young men agreed to this kind of thing, but I said, I cannot, I am getting older, and I am in a senior position in politics, and I will not lie about what I will do. So then, in 1991, I was sent to a military tribunal inside the prison.

Because I was president of the Journalists Association, I had set up a strike center downtown, where I had made a lot of speeches and talks about democracy before setting up the NLD with Aung San Suu Kyi. Because of this, they accused me of taking part in an uprising. There was no law I had broken, of course—this was a military tribunal and they didn’t go into details about the law.

I was tortured a lot at the beginning of my time in jail. I was interrogated and refused to answer questions and then I was beaten. They put their foot on my head so I could not see who was beating me. I lost all my teeth in the upper jaw right at the start, and without any teeth I had to eat prison rice—which was so hard and old—for eight years. Eight years with no dentures. Such beatings could happen any time, simply because they don’t like your manners or if they feel you are not very obliging to them.

I was kept in solitary all the time I was in prison. I never lived with other people, and I was locked up alone all day. I was never permitted to meet anyone else.

We only got prison meals twice a day. In the morning we got rice and beans or vegetable soup, and a little fish paste, and in the evening we got the same thing. Once a week we got some egg or meat as well—one portion only, which was two ounces. We were not allowed to get any meals from outside. Only at the family visits could we get things like fried fish and fried chicken.

Unless we were being punished for something, we were allowed family visits every two weeks, for fifteen minutes only. I did not have family come to visit me, though. I was single, and my parents were dead. I have got one sister, but when I went to prison she was working as a teacher, and—this is a tragic thing—she dared not come to visit me because she was on a government salary and she feared she would be sacked. So I was never able to see her. For six years one of my friends came to visit me. But then his daughter got cancer and he looked after her, and so another friend took over care of me for twelve years. Only when I was released did my sister come to me, and now she visits every month. She has children and grandchildren, and nowadays I see them too.

When we went out for the family interviews, they used to do full body searches on us. One of my friends—who is now in Australia—was so angry about this that one day he took off all his clothes and walked naked among the people. The officials were so shocked. They asked him to put his clothes on again. I don’t know what happened to him after that incident but I presume he was punished.

One friend of mine, another political prisoner, was the father of a baby daughter when he was arrested. She was too young at first to come for family interviews. But when she was about two years old, her mother brought her to meet her father in prison. The child was so happy, and she was asking about her father, and where he was, but when she came to visit, one of the prison guards was making the mother fill out forms and so on, and asked her many questions before they would give permission for both of them to see the father. The child thought that the man was her father! Ah, she was calling, “Papa, papa, papa,” and the mother got so angry and upset that she beat the child, and from then on the child never spoke about it. Both father and daughter are journalists now.

I would grind bricks on the floor and make a paste with water, and then I would use that to make chalk, and then I would write poems on the wall and memorize them.

Apart from the visits from my friend I couldn’t make any conversation because I was in solitary the whole time. The only time I saw others to talk to was when I was hospitalized. But I found ways to pass my time.

In prison I wasn’t allowed pen and paper. But I wanted to write, so I would grind bricks on the floor and make a paste with water, and then I would use that to make chalk, and then I would write poems on the wall and memorize them. But often I forgot the poems, and many got lost. I have only published a few since coming out. Others have been forgotten. One is called “The Tiger.” I wrote it when the weather was so bad and the roof was leaking and so many days were passing and I was suffering with my bad health and from brutality by the officials and so on. But I just thought: I don’t mind—one day I will be released, and until then I won’t be disappointed or lose heart, and nor will I change my political stripes. I felt was living like a tiger in a cage. I would tell my friends to memorize my poems and articles when I was able to see them during the family interviews. I would also use my chalk to write quotations and recitations from political and religious tracts for myself to learn.

There has been some change in prison life now. Prisoners are allowed to read and write. But when I was in prison, if they found a pen in your room then you would be punished—for instance, they would stop you meeting your family for two interviews. Interviews were only every fortnight, so if they banned you, you could not meet anyone at all for a month. I haven’t written much poetry since I came out of prison—I cannot concentrate properly and my poetic aspiration now comes second to my concern with politics and giving interviews.

I was not allowed contact with friends inside jail, but we found ways to communicate. For instance, I worked with Ma Thida in the NLD, and she was also in jail. Women are separately housed, so we had no chance to meet, but some of my friends whose wives were in prison occasionally had the chance to visit them, and I would give them a pack of noodles to pass to Ma Thida, and inside the noodles I would put a message. We had to cut the noodles in a way that was not visible and slot a letter inside. In prison, you had to be very imaginative—you had to have ideas, and find a way to carry them out. We were not allowed knives for cutting, but I would wait until I could get a piece of tin from a can of food, sharpen the lid, and use that. You had time enough in there to come up with ideas.

Very occasionally we could get paper for messages, using the slips in food packaging for fried chicken and so on. After a while we found ways to buy ball pens. The prison staff were corruptible. You could sell everything you got during family visits, even vitamin pills—there are always some buyers if you have something to sell. You even got real money in return. Political prisoners were not allowed to use money, but some prisoners were allowed to import it, as long as they gave 10 percent to the officer—they would just give word to their family that “the service man will come to you later, after the interview, and then you should give him 1,000 kyats.” After the interview, the service man would meet the family outside, the family would give him 1,000 kyats, then you would give 100 kyats of that to him, and then you could keep the money. We also tried to smuggle money inside edible things. You had to be ingenious.

I used to write messages to Tin Moe, a poet who later went to live in America. Back then he was also in prison, but in a different place from me. I would send letters to him in a cheroot. At the end of the cheroot there were some rolled-up papers from newspaper as a filter, so we would take that paper out, and all the tobacco too, and put in some rolled-up paper with a message, then give it to my younger colleagues who could move around more. They would pass it on to prisoners in his quarter who would get it to him. Once I had a chain of contact like that, I could send out pretty much anything. I couldn’t write a lot because of the size of the cheroot so the messages would have to be short. I remember, I wrote just three words to him after my meeting with an American congressman. I had met this congressman and told him our political program is to release all political prisoners and Daw Suu—so I just wrote three words on the piece of paper: “Suu,” “Hluttaw” (this is the Burmese parliament; we had elections in 1990 and the Hluttaw could not convene because the government refused to hand over power), and “Htwe” (this is a meeting convened for political dialogue).

As an alternative to paper for writing I also used the plastic wrapping of our food parcels. I would get a nail from the roof beam, grind and sharpen it to a point, and then write on the plastic by scratching, or if the plastic wrapping was very thin I would puncture the sheet with holes in the shape of letters. I would pass these on to other prisoners. But puncturing the plastic for messages was a laborious process. Sometimes it would take one or two days to write a message, especially since guards would be constantly walking around to check on us.

I would put Me Za, my crow, on my shoulder, and she would come along with me for some distance. You have to find ways to spend your time.

I also spent a lot of time with animals of different kinds. There were a lot of ants who would come in and out and down from the ceiling. I would put some water in a cup, get a dry leaf, and put two kinds of ant on the leaf and in the water, so they had nowhere to go with the water around them, and watch them ant boxing. Sometimes we got bits of tan ye, palm sugar, and I would take a tiny crumb of that and put it in a place where ants were not looking. When a searcher ant found the piece of sugar he would report back to the other ants. I saw him not as an ordinary ant but as an intelligence ant. When there was a piece of sugar big enough, he would go back to other ants, and they would come down to see the sugar for themselves—and then I would remove the piece of sugar again so the intelligence ant could not find the sugar, and I wondered if he might be punished or beaten for making the others look like fools.

There were many crows around too. Once I found a baby crow, took it into my cell, and fed it. When it grew up it was not accepted by the crow community because it had lived with humans, so it stayed with me. I named her Me Za: “Me” means black and “Za” stood for Zarganar [the Burmese actor, comedian, and critic of the military government]—and in Burmese language the word meza means exile. Legend has it that this word derives from a famous poet called Meza Taunggyi, who was sent into exile but wrote poems and sent them to the king, and his poems were so great that he was pardoned and called back to the nay pyi daw, the kingdom. When I would go out to see my friend for the family interview I would put Me Za my crow on my shoulder, and she would come along with me for some distance. You have to find ways to spend your time.

Stray cats were common in the jail. Our cell doors were just iron bars so cats could slip in. Some of the cats asked for food. We would get a small portion of meat every week but sometimes it was too hard to eat so we would just give it to the cats. They became messengers too. I had an inhaler for my chest, so sometimes I would put letters inside the inhaler, tie it to a cat’s body, and send the cat out. The cat would visit another cell and so the message would get passed on.

Sometimes snakes came into our cells. There were lots of bushes around the cells where snakes lived, and the rooms just had bars and not doors so they could get through, and at the back of the cell in the toilet there was a drainpipe which the snakes could climb over. When a snake came in I just had to throw my shoe at it so it would go away.

I did not always have a toilet in prison. For a long while I lived in a cell where we had to put our night soil in a tray with some ashes, and then in the morning we had to take it out by ourselves and throw it into a big pot. The first cell was about 9 x 12 feet, and it didn’t have a bed. I don’t remember how long I was in the first cell—I was in solitary, but they worried about me making contact with people and didn’t want to let other people know I was there, so I was always on the move, from cell to cell—I don’t remember how many times.

The worst place was the “doghouse.” I was sent there for seven months once as punishment for smuggling out a report on our prison conditions to the UN human rights rapporteur. The room was about 9 x 10 in size, with a small hole for light in the roof. I had already been in the prison more than seven years by then and I was over seventy years old, but I had to sleep on the floor, with no mat or sheet. I was given no medical assistance at all. I complained a lot of times, in particular I really needed dentures, but they didn’t agree to this for eight years. The whole time I was in the doghouse I was allowed no family interviews at all.

Special Ward was much better. It was called Special Ward because it always housed some senior politicians or privileged or supposedly dangerous political people. We were very close to the intelligence HQ there, where all the interrogation was done, and we could be kept under close watch by military men. I lived there right at the beginning, and again for three or four years at the end. At the back of those cells we had a bathroom with a toilet. You could put water in the toilet and you could get water from the tap to drink. It even had a little outside space, a small courtyard, above which there was a roof of iron mesh. I would then be allowed fifteen minutes to go out in the courtyard and sunbathe. The courtyard was only 9 x 10 or so.

We did manage to smuggle things in during our family visits other than food, mostly reading material. The prison guards helped—some were corrupt, so we would give them money, longyi, or shirts to bribe them to help us. Some were politically enlightened so helped voluntarily, but very few political guards dared to come to me because I was already such a well-known name, being founder of the NLD and the colleague of Aung San Suu Kyi, so they were afraid to associate with me. But anyhow I managed to obtain things and pass on messages through others.

I smuggled in lots of periodicals—The Economist, Newsweek, Asia Week—a variety. One day I got Time magazine and on its front page was a picture of Aung San Suu Kyi next to a picture of Khin Nyunt—the military intelligence chief, who was notorious and hated by the people. I translated this into Burmese on plastic sheeting to pass around for others to read, and I made a headline: “The Lady and the General.” In Burmese, when you shorten “general”, it can mean “death,” and I made reference to the cartoon story of the lady and the tramp. Other things I remember reading in prison were the biography of Mrs. Clinton, a book about journalists working while Blair was prime minister in the UK, and then I read a famous book, by a Scottish woman—oh, I know, Harry Potter! I read all of those books, I liked them very much. She is such a clever writer.

After a long time, five years in jail, I smuggled in a portable radio. I called it Radio Parrot, because a team of us would send out messages to others to repeat what was said on the radio. We had a chain of people for transmission. The first person who had the radio in his cell would listen to a program and take short notes about it, maybe on some plastic sheeting. That would be passed to the next person, who would decipher it into news form, and pass onto others, and finally one person who could get ahold of paper and pen would make it into news bulletin form, then we would pass that bulletin on to other people, cell to cell. That way we got the chance to publish and read articles about Burma and America. My jail news bulletin was called D-Wave—I could not publish it regularly, of course, but whenever I got a chance to. D stands for democracy. The current NLD journal called D-Wave is named after my bulletin. The only way we could pass it around from cell to cell was during bathing time. Sometimes it could even get passed over to other blocks. But it was hard to hide the radio. The search officers would come to visit our cells early in the morning, about 5:30 or 6 a.m., and they could come in any day. They only found out about the radio when the UN rapporteur publicized the report we smuggled out to him on human rights abuses in Burma’s prisons.

That is another story: over time we befriended the prison officers and servicemen, finding that many of them were corruptible, and I decided that we should ask for their help to collect human rights violations in prisons across the country so that I could compile them into a report and get it to the rapporteur. There are more than forty prisons in Burma. Some are harsher than others, but in most there is hard labor, ill treatment, and torture. The officers and servicemen rotate positions so that they don’t have to spend all their time in remote prisons, so we were able to collect a lot of facts from them. The report took a lot of organizing, but it was not all done by me. The officials didn’t want to deal with me because of my position, so they dealt with young men, and gave them all the information, and then I wrote up the paper, and handed it back to the young men to be smuggled outside. Our friends outside gave it to the rapporteur.

The report was announced in the news, and that was how the prison authorities found out. In 1995 they closed down the prison completely and searched all our rooms. All our flooring was dug up—and of course that was where everything we had was hidden in holes. They found all my writings, and the news bulletins. They were not kept in my room but in other people’s rooms who were not so suspect, but at that point everybody’s rooms were searched. They pinpointed twenty-four culprits, including me, sent us to the doghouse, and extended our sentences.

I was never tried in a court outside the jail, and no hearing was ever open to the public, even to family, and no lawyer was ever allowed.

I was sent to court again to be sentenced, with the others, but the court was inside the prison compound. We were not allowed to hire a lawyer. We complained to the officials about that and they said, All right, you can hire a lawyer—just give money to your family and they can do it. But because we were all being kept in the doghouse, that meant, among other things, that we were allowed no family interviews for seven months, so of course we had no chance to meet our family. We complained to officials about that, and they said they couldn’t help because banning our family interviews was an “administrative matter.” So we spent some two months in the courtroom with no lawyers. We were all tried together, while handcuffed. They did not ask us many questions. The chairman of the judges usually used to go to meet with military officers in a small room, and after a while we would be sent back to the cells again. Sometimes we would be sent to court at about ten or eleven o’clock, then after an hour we would be sent back to our cells. We had no chance to make submissions to the judges. I was boycotting the trial anyway, on principle, so I refused to say anything. Some of the young men would shout and so on, but it didn’t do any good. Altogether the group of us was sentenced for 117 years. I was sentenced for five more years. So altogether my sentence was twenty years, out of which I served nineteen years and a few months. I was never tried in a court outside the jail, and no hearing was ever open to the public, even to family, and no lawyer was ever allowed.

I got many other punishments when I was in prison. One was over my relationship with Aung San Suu Kyi. Early on the military said I was her “puppet master” because I had been a very close colleague with her in the party. They just wanted to show that she was being manipulated by someone, so as to minimize her influence, and I refused to admit it. This saw me punished further. There were lots of different punishments, like putting people in the stocks in the middle of the prison courtyard. They did not care how much they degraded us. I remember one official, making a speech to prisoners, who said, “We don’t care what you do, we don’t even care whether you die or not, but just die intermittently, not en masse—that way we don’t have to report to higher officials.”

I had bad medical problems, so I was occasionally sent to the hospital. That was the only time I got to meet other prisoners and talk. If they found my blood pressure was too high or my heartbeat irregular, I would be hospitalized in the jail’s hospital, but if I was seriously ill I was sent to Rangoon hospital in the Guard Ward. The jail hospital was not too bad—it was a two-story building, wooden, but quite good, built many years back by the British government, so of course the timber was good and strong, and it is still used as a hospital. It was better than the prison cell, anyway.

Finally I was released. But when I came out I had nowhere to live. Before prison I had my own house in downtown Rangoon, but when I was arrested I was evicted. Now I live in my friend’s house. His daughter built this small cabin for me, with a toilet and dining room and living room and a television room and my bedroom, so I can live alone. My life is simple. I didn’t eat dinner in the evening in prison for many years. So they just give me breakfast in the morning, and I am not much trouble for them.

People as a whole in the country still feel as if they are in prison, even though there is no wall around their houses or streets.

When I came out I started to work again with the NLD immediately. I had to—I was a founding member. On the very first day I was released, that evening, I met with the media men in my house and told them that although I am free now, I don’t feel I am really free, because there are still restrictions on what I can do and say, and also because people as a whole in the country still feel as if they are in prison, even though there is no wall around their houses or streets. So I told them I would work for all these people to be free as long as I live, and that I would wear blue shirts like prison uniforms as a symbol for the political prisoners left behind. Although I am a politician I still feel even now as if I am a political prisoner. I still show solidarity with those political prisoners, and not only that—I actively help with all my earnings. When I sell my books I give them my royalties. Last year I also formed a foundation for political prisoners—the Win Tin Foundation.

I have no grudge against the military rulers and junta members, but I cannot forgive and forget, as long as they don’t change their minds, practices, political ambitions. How can we forgive? Thousands of people are dead, in prison, and so on.

My most important priority is still democracy. I want to achieve that. I want freedom and liberty in our society, because we lost this for such a long time. Most people in the country have had no real experience of democracy. So nowadays what I care about most is liberty in society, freedom of press, freedom of expression, freedom of assembly, and an end to oppressive laws.

Burmese writers have lived under the censorship law for such a long time that they have it sitting there on their backs, weighing them down.

I think the Press Council should be more independent—it was appointed by the government, not like the Press Council I formed fifty years ago. I am afraid that the current progress of media law reform is showing that press freedom can’t yet be achieved in a country like Burma, which has been ruled for so many years by a military junta. While the government says they are changing, their mentality has not actually changed much. They are still not happy about the prospect of free expression.

And even though the censorship board is now scrapped, censorship is still in the minds of Burmese writers. They have lived under the censorship law for such a long time that they have it sitting there on their backs, weighing them down. So nowadays they are practicing their own censorship. That’s a problem. There are journals, about 300, but most of the writing they contain is still about trade or health and so on—just reporting facts. There is not much expression of thought, and few leading articles that express opinion. Not only that, but the journals rarely produce other people’s opinion articles either. There is little op-ed. The reason is that they are anxious about the implications of expressing their opinion. In Burma, although it is said there is no censorship law anymore, and that there are now many journals, presses, and some semblance of a free press, actually there is not much real freedom.

The constitution is a big problem. As it is now, it is just expressing the old principles of the regime. Every aspect of it needs to be changed, including on matters of demonstration, judiciary, and nationality. There is a movement for constitutional reform now, and I think it will be reformed, but I don’t know how much. Even if it is reformed, many things that are already mentioned in the constitution can’t be practiced in reality. For instance, the constitution mentions the right to demonstrate, but in fact legislation in place says that you have to get advance permission from the police to do so, and they never give permission. And the constitution still contains principles such as the non-disintegration of national solidarity. I have been in the media world for more than fifty years, and I remember when this type of wording came in. It has been normal for a long time now, and it still reflects the mentality of the old military rulers. And as long as all such wording remains in place, there will continue to be oppression. So I say please try to reform the constitution and to make news laws that support the media, instead of laws that restrict our movement and our expression.

The Tiger

The sun might be searing,

Or it might be smothered by fog.

The air might be chilly,

Or it might be piping hot.

But in this narrow room,

Light cannot enter,

Air cannot enter,

You cannot see the sun,

You cannot see the moon,

You cannot see anyone.

You can sit and stare,

You can sleep or think,

But you cannot sing a tune, let alone get the news.

You cannot write a poem, let alone read a few.

You cannot even talk, let alone state your views.

Excluded from the hubbub of life,

My world is a tiny cell.

I pace round it and gaze through the bars,

All day and half the night as well.

Yesterday was a waste,

Today is a waste,

Tomorrow will be wasted too.

Waste.

Waste.

A waste of all I could do.

But be it a day or a lifetime,

A month or a week, a year or an era,

I will never submit.

While an anvil I may be beaten,

But once a hammer I will hit.

Truth is on our side.

People are on our side.

God is on our side.

But when will they realize?

See that tiger in the zoo,

Rolling in a cage,

Do they think it has turned harmless?

How wrong, and how hilarious!

I ask you to remember this.

As long as it bears black stripes on gold,

Vivid and distinct,

It will always be a tiger.

Fearless and fierce.

Adapted from Saffron Shadows and Salvaged Scripts by Ellen Wiles. Copyright (c) 2015 Ellen Wiles. Used by arrangement with Columbia University Press. All rights reserved.

Ellen Wiles is a British writer, human rights lawyer, and scholar specializing in literary culture. She lives in London. She can be found on Twitter @ellenwiles.

Win Tin was a writer, journalist, editor, and politician who co-founded Burma’s NLD party with Aung San Suu Kyi and was a political prisoner in the country for nearly twenty years.

To contact Guernica or Ellen Wiles, please write here.