Henry Simon | Industrial Frankenstein

By Roslyn Bernstein

My association with the left goes back to my high school years in Long Beach, NY. It was there, in a friend’s basement, that I first read issues of the Communist Party newspaper, The Daily Worker. Several of my friends’ parents had been thrown out of the New York City school system during the McCarthy years and they had gone into hiding in this small beach town, 45 minutes outside the city. Occasionally, I saw flyers and posters in the basement, too, demanding better working conditions and higher wages for the proletariat; they were left over from rallies in Union Square and from secret meetings in Greenwich Village.

I bought and read John Reed’s Ten Days That Shook the World, originally published in 1919. My Modern Library Edition from the 1950s included a foreword by Lenin and an introduction by Granville Hicks. Inspired by the book, I traveled to the Thalia Theater on the Upper West Side, famous for showing avant-garde films, where I was mesmerized by Sergei Eisenstein’s footage for October: 10 Days that Shook the World, a film produced on the 10th anniversary of the Russian Revolution. The film, filled with stark and powerful black-and-white images of workers and technology, traced the defeat of the provisional government and the triumph of the Bolsheviks set to music by Dimitri Shostakovich. What could be more exciting than the opening footage of the film with revolutionaries tying ropes around the head and torso of Alexander II, Emperor of Russia, and then crashing the statue to the ground?

Hearing Herbert Marcuse lecture on Communist philosophy at Brandeis University in the early 1960s took on a more personal meaning when I discovered that Nikolaus Basseches, allegedly a distant cousin on my mother’s side of the family and an Austrian journalist who reported from Russia, had authored Stalin, the first biography of Joseph Stalin, published in translation by E. F. Dutton in 1952, one year before Stalin died.

The artists shunned the traditional landscapes and portraits of bourgeois art, turning their attention instead to such socially conscious issues as the class struggle, labor organizing, immigration, socialist mysticism, utopian communities, and racial justice.

So, when word arrived that The Left Front: Radical Art in the “Red Decade,” 1929-1940, would be opening at NYU’s Grey Art Gallery, I was happy to revisit the art of this era. Organized by the Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art at Northwestern University, and expanded to include documentary material from NYU’s Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, the Grey exhibit focuses on activist artists who, following the Great Depression, sought to define and produce art that was socially engaged.

Under the auspices of the Communist Party, the John Reed Clubs (JRC) were founded in New York City and spread to thirteen other cities after the stock market crash in 1929. The JRC and their less doctrinaire successor group, the American Artists’ Congress (AAC) 1935-1939 embraced the idea of “art as a social weapon,” according to co-curators John Paul Murphy and Jill Bugajski, both recent PhDs in art history from Northwestern University. Whether the artists used printing presses or brushes or cameras, Murphy said, they shunned the traditional landscapes and portraits of bourgeois art, turning their attention instead to such socially conscious issues as the class struggle, labor organizing, immigration, socialist mysticism, utopian communities, racial justice, and the Spanish Civil War.

The timing for mounting an exhibit on the history of art in political activism was perfect. It was the fall of 2012, after America had finally recovered from the worst recession since the Great Depression, after the Occupy Wall Street Movement had spread from the financial district in lower Manhattan to around the world, and after the upheavals of the Arab Spring promised to topple long-time governments in the Middle East.

Poking through the substantial print archives at the Mary and Leigh Block Museum of the Art, Northwestern University, where he was then a fellow, Murphy noticed that many of the artists in the Block collection had one thing in common: they all belonged to John Reed Clubs. While previous exhibits focused on these artists as WPA workers, immigrants, and Jewish artists, “no exhibit had focused on their political edge, on the link between their activism and art,” Murphy said. “Their prints reminded me of what was in the air in 2012. I decided that it was the opportune moment to see how artists responded in the 1930s and what we could learn from their experience.” The Left Front’s original exhibit ran at Northwestern’s Block Museum from January to June, 2014.

Conceived as a modest exhibit for a small space, the project ballooned as Murphy and Bugajski drew upon their shared interest in the visual culture of socialism and activism, Murphy focusing on the Arts and Crafts movement from1880-1910 and Bugajski on the art of the 1940s. Their collaborative decision, Bugajski explained, “was to organize the show around fine art prints,” although many, if not most, of the artists in the exhibit, displayed their art in the press—in periodicals, newspapers, magazines and poster art. Several were cartoonists including Henry Simon, Hugo Gellert, and William Gropper, who drew thousands of political cartoons for Liberator and New Masses. They published brave and often defiant work, focusing on images of class, race, and gender prejudice in the club journals, New Masses (1926-1948) in New York and Left Front (1933-1934) in Chicago. They supported the rights of prisoners, and they taught art to the working class through JRC programs.

“These were artists who would have said, ‘Je Suis Charlie’ for sure,” Murphy said. “They made bold statements about the world. When we looked into the 1930s, we saw their criticism of bureaucracy, police brutality, the church, and racism.” The decision was made to organize the show chronologically and thematically, with the first half oriented around the JRC and the second around the AAC.

The manifestos of both groups hang prominently in the Grey Gallery exhibit, displaying their vastly different rhetoric. The six points in the John Reed Club Manifesto all begin with the word Fight while the language of the AAC Manifesto is less harsh and more inclusive; it is obviously an effort to bring together a coalition of the enemies of Fascism. During the five years of its existence (1929-1934), the JRC was militantly anti-capitalistic, brought on by the events of the depression when there was a 50 percent unemployment rate in the United States. “But the rise of Fascism, turned the lens of its successor, the AAC, to what was happening in Europe and the Spanish Civil War,” Bugajski said.

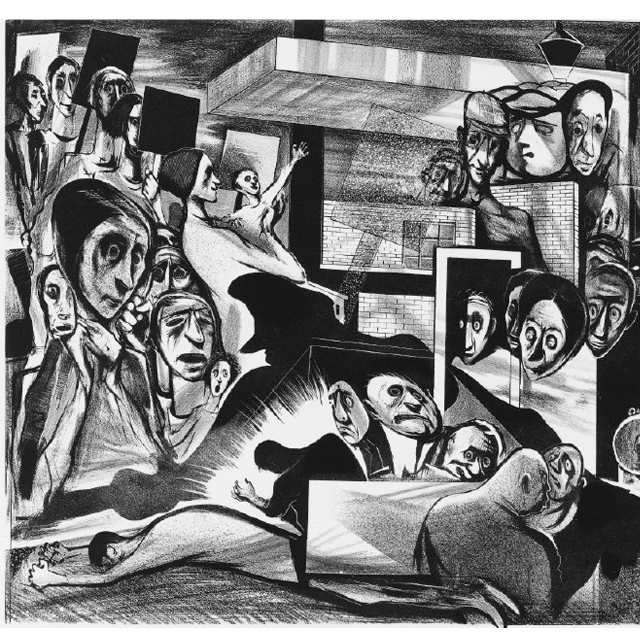

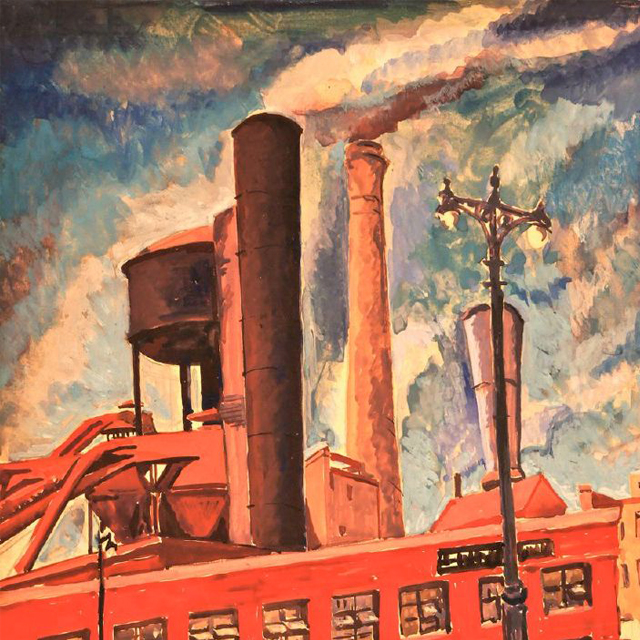

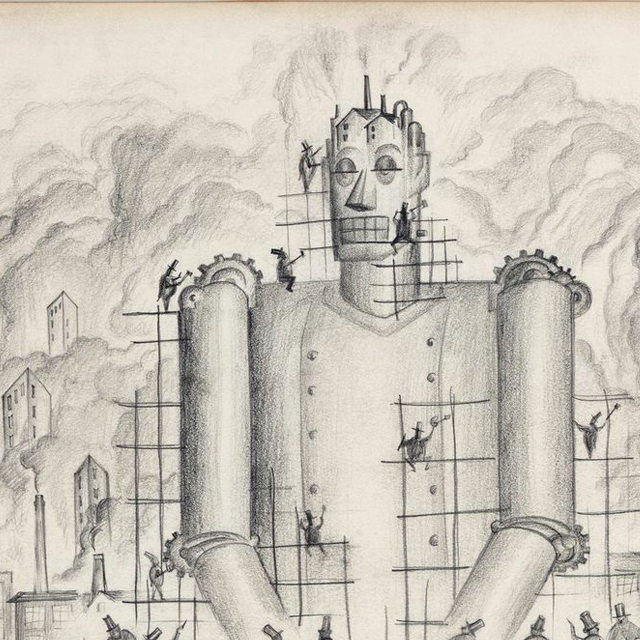

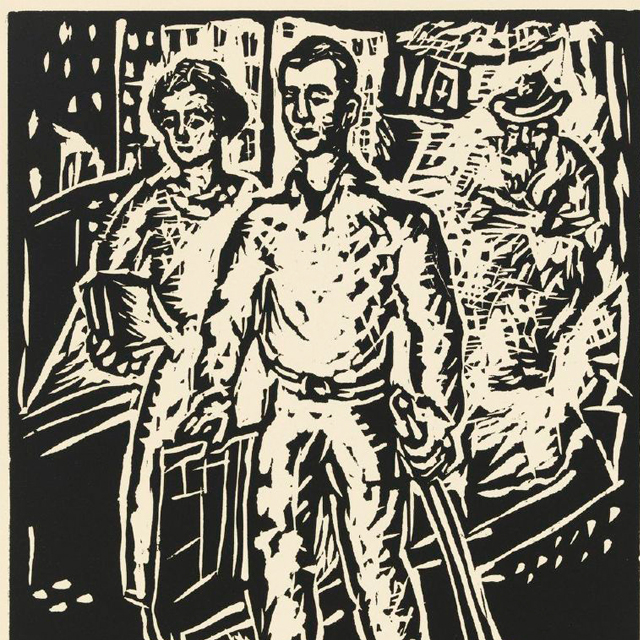

Thematically the exhibit is divided into four sections, the first two using Marxist categories and slogans, The Class Struggle and Workers of the World Unite! Included in the second section are two subsections, one on Industrial Frankenstein featuring Henry Simon’s drawings/designs for a diorama for the Chicago’s World Fair. Progress, as interpreted by Simon, was a Frankenstein monster built by fat-cat Capitalists. The other is a subsection on Scottsboro, where activist artists lobbied for interracial solidarity.

Section Three, What is Revolutionary Art, resists the notion that art of this period is best described by the term social realism to show that the artists of the 1930s were truly diverse. They debated the nature of revolutionary art, with many rejecting the idea that it was solely about workers with raised fists. Instead, several artists substituted abstract or surrealistic visions of the struggle.

They rejected the bourgeois definition of an artist as a genius aloof from his or her historical moment.

Opening the Grey Gallery exhibit is a wall-size blow-up of a photograph of a protest march held in 1934 by the John Reed Club and the Artists’ Union, the first Artists’ Union ever organized by the JRC. Shot by an unknown photographer, the photo shows protestors carrying flags and placards with the words: “Artists Fight Against War and Fascism.” They represent the new “culture workers” or “worker-artists,” their self-designated description, curator Murphy writes in the gazette that accompanies the exhibit, one that could easily be rolled up and carried to a march. “They rejected the bourgeois definition of an artist as a genius aloof from his or her historical moment.” It is indeed ironic that, despite their proletarian leanings, all of the marchers here are formally attired in suits, ties and hats, the standard dress of the time.

Featured in the Class Struggle section of the exhibit are works by Morris Topchevsky, Ernest Fiene, Reginald Marsh, Boris Gorelick and Henry Glintenkamp, who was a student of Robert Henri and shared a studio with Stuart Davis. Gorelick’s lithograph, Industrial Strife (c. 1938), depicts the sunken faces of workers, some standing and some prostrate, a grouping of bosses, with inflated, bald heads and white shirt collars, a large black shadow of a policeman with a club, all in a factory setting amidst wheels and other machinery. The style is surrealistic and the message unmistakable: workers are downtrodden. Glintenkamp’s Voter Puppets, a wood engraving from 1929, depicts a puppeteer, clearly an industrialist in a black coat with a top hat, his arms raised, pulling the strings of marionettes (the workers) on a stage. Behind him, workers in identical suits and hoods are lined up like robots to drop their votes in the ballot box.

While most of the 100 works in the show by 40 artists are woodcuts and lithographs, mediums suited to printing multiples, Morris Topchevsky’s Unemployed, (undated), an oil on canvas, and Down with Capitalism, (c. 1930), a watercolor, ink and graphite, convey workers’ frustration with softer brush stokes and muted color, although Topchevsky was one of the most radical of the artists, actively involved in the Chicago branch of the John Reed Club. It has not been a good day for two workers seeking jobs in Topchevsky’s painting. One is slumped over, leaning on his arms, which are folded in his lap, his head obscured by a big hat, his pants revealing thin legs and too short blue socks. The other sits staring off into space, his hat tilted over his head, in one hand, the day’s newspaper with the help wanted ads, almost fallen to the ground. Clearly, he has had no luck.

The case here includes printed materials, some from NYU’s collection. There’s the May 1933 issue of New Masses, the monthly publication of the New York chapter of the JRC (1929-1935), a copy of William Siegel’s The Paris Commune: A Story in Pictures, (1931), a 1919 edition of John Reed’s Ten Days That Shook the World, and a 1931 pamphlet from Amerikanskiye Khudozhniki “Dzhon Rid Klub,” American Artists of the John Reed Club, with a dramatic drawing of a worker in a bright, red jumpsuit on its cover.

Class Struggle is followed by Workers of the World, Unite! a section that focuses on labor and the struggle to organize. Thematically, much of this art work depicts factory and construction workers and seasonal farm hands, all of whom suffer from poor working conditions, no benefits, and low pay. Two etchings and aquatints by Blanche Grambs, one of several women in the show, are especially notable. In Grambs’s Mill (c.1935-1937), the rooftops of the mill buildings form a stunning geometric pattern. Nearby, Riva Helfond’s Miner and Wife (1937), depicts the couple’s grim faces. The miner wears his cap with its light. Prominently placed in the work is his hand, clenched in a fist.

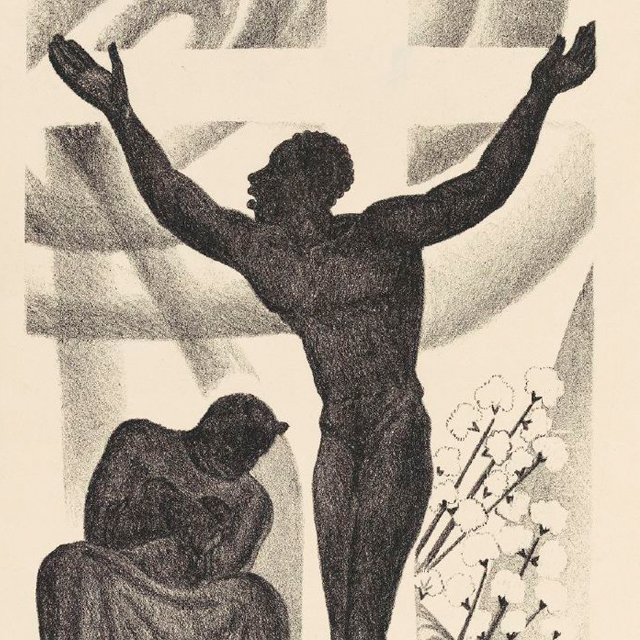

The Scottsboro subsection, both on the wall and in the accompanying case, makes it clear that to these artists racial solidarity was class solidarity. The synergy between prints and printed matter is apparent in the work of Prentiss Taylor, whose illustration for Langston Hughes Scottsboro Limited: Four Poems and a Play in Verse, (1932) can be seen in the case whose lithographs hang on the wall. There are three here, most compelling his Christ in Alabama, from the portfolio Scottsboro, 1932, where one of the black teenage defendants is depicted as Christ on the cross.

Despite their agreed-upon activism, though, there was considerable disagreement over art. Attracted to Russian-style social realism and European modernism, activist artists struggled to forge an American aesthetic, a theme explored in the section What Is Revolutionary Art? The debate over how best to look at the world often came down to those who favored abstraction vs. those who insisted that art with a social message needed to be grounded in recognizable figures and objects.

The variety of styles here punctures the prevailing epithet of socialist realism inspired by a cold war mentality. Side by side, there is the American realism of Isabel Bishop and the 14th Street School, surrealism, and Stuart Davis’s modernism. His lithograph New Jersey Landscape (Seine Car) 1939, a flat, geometric abstraction.

Diagonally opposite this work is a printing press that belonged to Alex Topchevsky, Morris’s brother, included in the exhibit to emphasize why and how prints threatened the gallery system where the single, painted canvas was valued. The press is small, easily fitting into an individual artist’s studio. Framing it, are two posters one for a color lithography workshop taught by Margaret Lowengrund at The New School. So many of the New York City-based JRC and AAC labor activities and so many of the artists’ studios were located near the Grey Gallery, that it is particularly fitting that this show has a Greenwich Village venue.

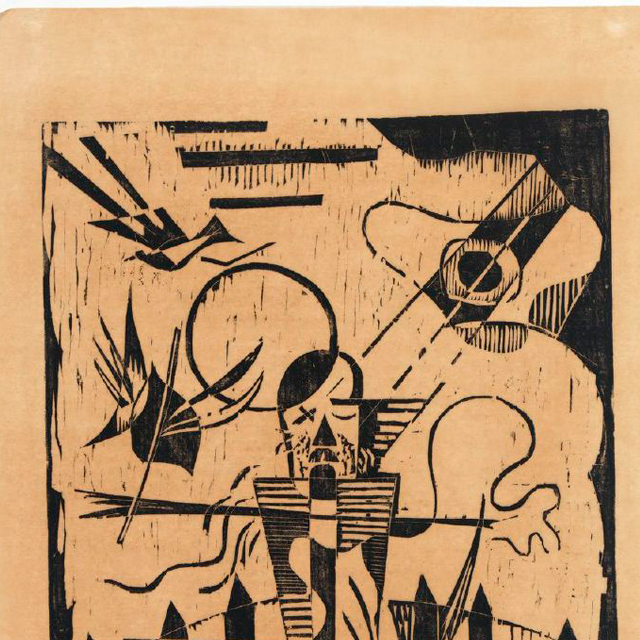

The last section of the exhibit, The Popular Front, focuses on activist artists in the period after Hitler seized power in 1933. Werner Drewes’s woodcut, It Can’t Happen Here, from the portfolio It Can’t Happen Here, 1934, references Sinclair Lewis’s novel, published around the same date. Colloquially called, The Broken Swastika, the work is a geometric abstraction but it is nevertheless recognizable as a political symbol. Threatened by Fascism, art had a definite role to play. The bombing of the Basque town of Guernica by the Germans, who were supporting General Franco during the Spanish Civil War, provoked American activist artists. This is apparent in Henry Simon’s Bombing of Guernica, a graphite and colored pencil work from 1937, created the very same year as Pablo Picasso’s Guernica, which was on view in his first retrospective in America at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) from November 1939 to January 1940. Mitchell Siporin’s watercolor Spanish Civil War (after Goya), 1941, references Francisco Goya’s The Third of May, 1808, an oil on canvas. Known as a court painter, Goya, like many of the artists in this exhibit, was also a printmaker. At its peak in 1939, AAC boasted about 900-artist members although in 1940, one year after Stalin signed a non-aggression pact with the Nazis in August of 1939, only 15 percent of AAC members renewed their membership.

Set on one wall as a parenthetical moment is The Biro Bidjan Portfolio, a complete set of prints by Chicago’s progressive Jewish artists. It was created as a gift for a new art museum in Biro-Bidjan, a region in Siberia that Joseph Stalin sought to establish for Jews. With the rise of Nazism, American artists supported this utopian idea, convinced that it might provide Jews with a safe haven, an area where Jews, with their Yiddish language and culture, could survive and even thrive. Included among the artists here are Todros Geller, David Bekker, and Bernece Berkman, whose woodcut Toward a Newer Life resonates with Picasso’s Guernica. Two hundred art works were sent but they got lost and never arrived.

In many works, one feels an undercurrent of apocalyptic yearning.

Social Mysticism, the title of the last section of the exhibit, is a description that both curators claim as their own. “It was a way that these artists drew on allegory and romanticism,” Murphy said. In many works, one feels an undercurrent of apocalyptic yearning especially in Rockwell Kent’s lithograph Solar Flare-Up, (1937). Out of the shadows of the art of the raised fist, come experimental prints by Kent and Carl Hoeckner, in whose lithograph The Death of Truth, (1936), military helmets are hidden in the dark background.

A ten-minute color film shot by John Albok of the 1937 May Day Parade in New York in the last room reminds viewers that art was deeply entwined with intervention. The activists march triumphantly with their placards and posters and they ride on elaborate floats. There is the sense of power that comes from thousands of bodies in one space. But the moment of triumph is short-lived. The exhibit ends on a melancholic note with Julio de Diego’s Industry Becomes More Complex, (1943) and the larger truth that activist artists could not prevent World War II.

The Left Front: Radical Art in the “Red Decade,” 1929-1940 runs from January 13-April 4, 2015 at the Grey Art Gallery, New York University, 100 Washington Square East.