In October of 2011, I drove to the town of Mesilla, New Mexico to watch a screening of El Sicario, Room 164, a documentary about a cartel hitman who tortured and killed hundreds of victims in Mexico. I arrived late and was turned away at the box office. As I stood in disappointment outside the tiny Fountain Theatre, a man lurched through the door and into the daylight, disheveled and dressed in faded jeans, boots, and a vest. It was Charles Bowden, the writer and co-producer of the sold-out film. I approached him timidly and introduced myself, telling him I was a Border Patrol agent who had come from El Paso to see his movie. Bowden looked at me, less surprised than I expected, and patted me on the back. He ushered me inside the adobe building, ignoring the ticket collector who grumbled about the lack of seats, and left me in the care of an elderly usher. She walked with me to the concession stand, where they refused to take my money, and then led me to an empty seat in the back.

I had become familiar with the work of Charles Bowden only a few years earlier, shortly after beginning work for the United States Border Patrol. At the time I was living in a remote corner of southwestern Arizona, trying to come to terms with day-to-day existence in a desert devoid of pity. I began with Blue Desert, a collection of essays that includes an account of a forty-mile border crossing Bowden made in the summer of 1983 through the same desert terrain I was then patrolling. “They play a game here but nobody watches from a box seat,” he wrote. As someone new to the game, I valued Bowden’s compulsion to walk along migrant trails, to see and understand things as they were, not as he wished they might be.

For Bowden, to live and write in the Southwest was to ceaselessly reconcile scenes of natural beauty with human perversion.

Much of Bowden’s early writing came out of his experiences working at the Tucson Citizen, a now-defunct daily newspaper where he spent three years reporting on immigration, murder, and sex crimes. Of his time there, Bowden later wrote:

“I would quit the paper twice, break down more often than I can remember, and have to go away for a week or two and kill, through violent exercise, the things that roamed my mind. It was during this period that I began taking one-hundred-or-two-hundred-mile walks in the desert far from trails. I would write up these flights from myself, and people began to talk about me as a nature writer. The rest of my time was spent with another nature, the one we call, by common consent, deviate or marginal or unnatural.”

For Bowden, to live and write in the Southwest was to ceaselessly reconcile scenes of natural beauty with human perversion.

Bowden spent most of his life in Tucson, where he established himself as a true “desert rat” and a staunch defender of the Southwest’s arid landscapes. He became close with Edward Abbey, the notorious author of The Monkey Wrench Gang, whom he credits with inspiring him to leave newspaper reporting and write on his own terms. Although Bowden wrote passionately about the natural world and regularly held court with ecologists and environmental activists, he seemed unable to look away from the relentless social plights he had encountered as a crime reporter.

“In Juárez you cannot sustain hope,” Bowden wrote. “We are talking about an entire city woven out of violence.”

In the mid 1990s, on a visit to Ciudad Juárez, Charles Bowden came across a photograph in the back pages of a local newspaper that would change the course of his writing career. The image was of Adriana Avila Gress, a maquiladora factory worker kidnapped, raped, and killed in the still-early years of the Juárez femicide. Haunted, Bowden kept a copy of the picture for years in a folder on his desk. The murders of women in Juárez continued for over a decade, only to be eclipsed by the unprecedented storm of drug war killings that began in 2008. Obsessed with understanding the city’s dire social and political intricacies, Bowden eventually moved from Tucson to Las Cruces, New Mexico, barely an hour’s drive from Juárez. In his subsequent work, one could sense the darkening of his worldview and the diminished presence of nature. “In Juárez you cannot sustain hope,” Bowden wrote. “We are talking about an entire city woven out of violence.”

As I read through this bleak turn in Bowden’s work, I began to regard his vision with great trepidation. During those years I was careening wildly through the hard realities of the Arizona desert, chasing border crossers and drug runners, offering meager comfort to migrant children and pregnant women, and retrieving from the wilderness dead bodies and stammering men who had forgotten their names in the heat. Grim scenes lingered in my mind and teetered into nightmares. In an essay on the years he spent reporting on violent sex crimes, Bowden wrote, “I do not want to leave my work at the office. I do not want to leave my work at all. I have entered a world that is black, sordid, vicious. And actual. And I do not care what price I must pay to be in this world.” But I was not like Bowden; I feared the price I might pay to remain in such a place.

In his later years, in appearances on news programs and in documentaries, Bowden would sometimes seem on the verge of coming unhinged, as though exasperated at describing, in layman’s terms, the scale of destruction swirling across Mexico and the borderlands. As Bowden saw it, the Mexican government, through its deployment of police and military forces and their complicit dealings with drug cartels, was engaged in the wholesale slaughter of ordinary Mexican citizens—a kind of “social cleansing” perpetrated with the financial support of the US. But I struggled to comprehend how Mexico’s shifting colossus of violence could possibly be something designed and orchestrated with intention. Perhaps I was naive, perhaps I was fearful of the implications, but I felt unable to follow Bowden into that place; I could not hazard myself to believe something so sinister.

While Bowden brought back dispatches from the abyss, I could only hover at its edge. For me, for most of us, a glimpse of the void is enough, is already too much.

In his book Murder City, Bowden declared, “you cannot know of the slaughter running along the border and remain the same person.” In 2011, I left the Sonoran Desert of Southern Arizona and drove across the Chihuahuan grasslands to the city of El Paso, Texas. On a nightly basis I beheld the shimmering lights of Ciudad Juárez with staggering dread and compulsion. During the time I lived and worked in El Paso, I never once went to Juárez, I never crossed over to the other side. While Bowden brought back dispatches from the abyss, I could only hover at its edge. For me, for most of us, a glimpse of the void is enough, is already too much.

Inside the crumbling Fountain Theatre in Mesilla, New Mexico, the credits rolled and the house lights came on. As the crowds dissipated, I approached Charles Bowden once more and thanked him for getting me into the movie. He seemed to tower above me, but spoke to me with calmness and measured warmth. He asked how I liked the Patrol, and we stood for a while talking about Arizona’s wild places, about Ed Abbey and the desert rats. We didn’t speak of our dark work on the border, of the dead migrants in the Arizona desert or the cartel killings in Juárez. We talked about landscapes, about plants and vanishing animals, and about walks in the desert far from trails.

Francisco Cantú served as a Border Patrol Agent for the United States Border Patrol from 2008 to 2012. He is also the recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship. A frequent contributor to Guernica Daily, his writing has appeared in South Loop Review, J Journal: New Writing on Justice, and in Dutch translation at De Groene Amsterdammer.

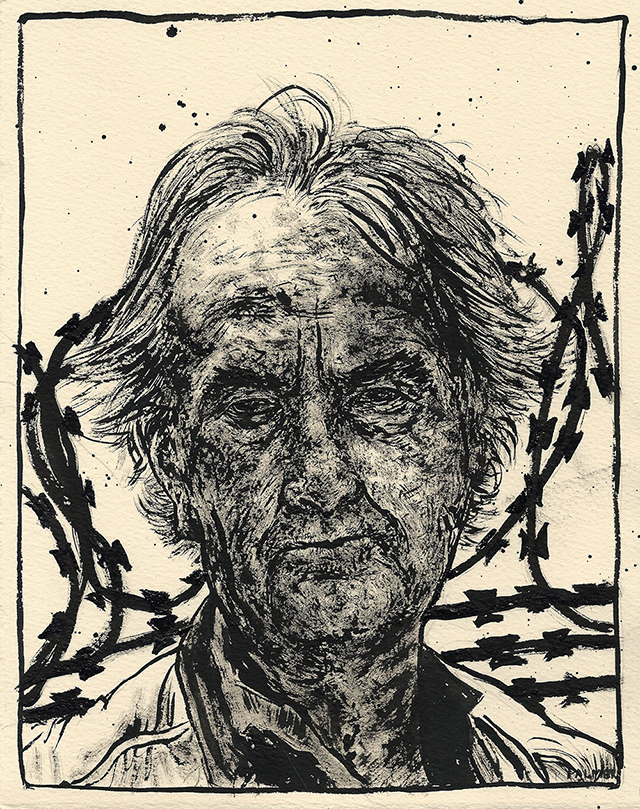

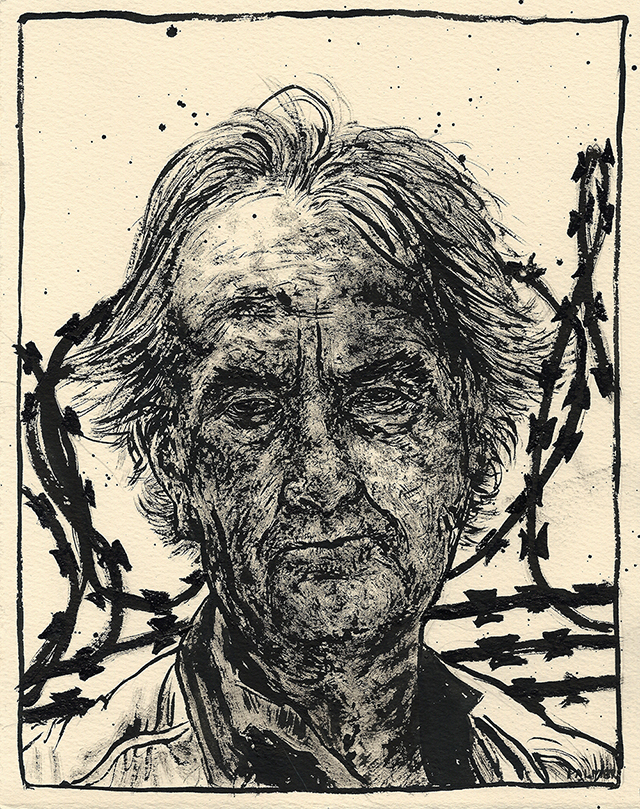

S. Jordan Palmer was born and raised in Prescott, Arizona. Coming from a small mountain town, there was ample time to spend alone drawing, reading, and thinking of crazy shit. This pastime quickly became a passion, and is now more than that. A regular studio practice is the only thing keeping him out of trouble.