There’s this woman I see, usually once a week but sometimes more, who is lately always telling me about her husband. He was a negative force in your life, I tell her. But he did it so positively! she says. I’m not easy on her. I’ve been seeing her for years. So far as she says, the guy was a lazy lump with a guitar and a part-time job where he had to wear a name tag, so I tell her that some men are like hair; they need to be cut off to grow back stronger. And I tell her that these are her best years, and there’s only so much makeup can do. She should sign the papers and go back to going by Miss. I think Margarita appreciates the honesty, or else we’ve had a relationship too long for her to find someone who knows her like I do, the texture and cowlicks, the inky kinks, the volume where it gets to be too honky-tonk for her, though I’d call it Bridget Bardot.

“Anyone you want,” I tell my girls. “Just tell me who, and I’ll make you anyone you want.” And these days, generally, she is not aiming for Bridget.

Most of my girls come from Next Door, Next Door being the topless spot. They want me to blow them out or sew the hair extensions in extra tight, so they don’t lose them whipping around the pole. They want highlights and dye jobs and to look good enough that the creeps are worth it. Margarita used to be one of them, but now, bless her, is a nurse. I lose most of them when they stop dancing, though there are some who still come around, new nurses and lawyers and homeowners. “Jolene, you’re a catch,” the loyal ones explain, but I know that blandishments are in a stripper’s nature. What they mean is, I’m cheap.

I’ve been flown, so you’d think I’d have arrived by now. A few years back, a production company bought me a plane ticket out to Hollywood so I could make the star’s faces. I let my sleeping-dog boyfriend lie in the bed he made for himself and packed my gamut of skin tones in powder, cream, and sheer formula form. I touched famous faces by day and looked at their pictures in magazines at night. It was like being in a movie, but tactile. Then pink eye took a week out of filming, and I was the one carrying the infection in my compacts, they said. I bought a ticket to New York City and the salon took me when even soap operas wouldn’t. I didn’t tell the girls a new look would change their lives. I told them, If it looks like a duck, it must be a duck, and left the walking and talking up to them. That’s why some still come back.

But it’s true. For example, when you have a gap between your two-fronts, people will assume you’re dumb or trailer. This was one problem I had until recently. So I saved up several years and bought myself a mouth full of metal. I say you don’t have to put up with anything you don’t want to, even if it’s part of yourself. I’ve dropped girls who made appointments and didn’t show. You see, it’s not really what they’re doing; it’s what I’m not doing. When they don’t come, I can’t even get my hour of their lives. I’m alone in this prairie plain of being me. These girls. They don’t know what they do to me.

A few weeks ago, I didn’t get a cancellation from one of the former next-door girls. I had a name penciled for the Saturday last cut, and she never showed. I’d come into the salon sore with improvement. Earlier that morning, I’d gotten my braces tightened. It was the first time, and I hadn’t counted on my mouth getting so cut up. I’d go in the bathroom to spit blood-pinked saliva.

“There’s blood in my mouth,” I complained to Celeste, the receptionist. Everyone else had their hands in people’s hair. She ducked her head and looked side to side as though she was about to cross the street.

“Like, murder?” she whispered. “What have you done, Joley? Why?”

“Just tell me if anyone comes in.” That girl is half an idiot savant.

Normally, I would have scuffled my tail home, but the no-show had booked three hours—cut, color, and style, that she didn’t end up using. I watched the clock and touched my braces with my tongue, hoping someone who hadn’t prepared to get beautiful would stop in. That happened, I knew. People would decide they weren’t a woman who let a man put his hands on them and go out to get themselves some pink hair. The bells hanging on the door shook as it opened.

The ones I took were a new pair, snotty girly homos whose hook at the club was that they were sisters. They wore matching dresses sized like scarves that let their holes hang out. Mickey and Minnie they called themselves. I think of them as The Rats. I don’t care what the hell gets anyone’s bread risen. I just didn’t like how they acted like they’d tricked the system.

So The Rats sat there talking about the little black baby they were going to adopt and how it was only going to eat vegetables from the Hudson Valley and no bread at all. He’d be given dolls and trucks and soy milk. When he was three, they’d explain to him that he peed out of his urethra just like girls did so he didn’t develop a patriarchal superiority complex. I combed Minnie’s hair while her fake sister sat flipping through the dye swatch book.

“I brushed Michael Bolton’s hair once,” I said, “and moisturized George Clooney too.”

“Do you know that once at the grocery I saw a woman spank her little boy right in the middle of the produce section?” Mickey said. “It’s like, what do you think your child is going to learn from that?”

I’d personally learned a lot of things that way, such as don’t talk to strange men and don’t accept anything from them either, don’t steal candy from the store, and do your part instead of letting your mother and sister do all the work. “My daddy striped me up with a belt, and look how I turned out,” I said.

“A hairdresser,” said Minnie. She stared right at me through the mirror, and Mickey choked on her to-go latte laughing. The two of them slapped their knees, and some of the foil from Minnie’s head fell to the floor.

“I brushed Michael Bolton’s hair once,” I said, “and moisturized George Clooney too.”

“Congratulations,” they said. But they were laughing and calling jinx and clapping their hands. One of them was wheezing to the point she sounded like she was dying, or else that was my own positivity shining a little light.

For a moment I thought I’d like to leave their hair half done and let them walk ten blocks in public to the next salon. They’d look as twisted up as they were. But there’s an expression my pops told me when I was a kid that won’t let me forget it: “Don’t be too poor to paint and too proud to whitewash.” I stuck it to them the only way I could, charging them authentic prices for polyester hair. It was never about money.

So when they’d left and the hair was swept, and I was sitting at home with cooling takeout, I decided to call the cancellation. It wasn’t exactly her fault, The Rats, but it wasn’t quite not her fault either. I’d tell her that whatever the excuse it was meager enough that her dog better be shitting homework. No one picked up the phone. I called again. Then once more. A hairdresser!

Later, when I’d let the television smooth me down some, I thought it was better the call never went through. There was this magazine article I’d read once called “How to Be Angry the Right Way.” The author, a Dr. B.D. Gillman, had been inspired by the Greek words “Anyone can be angry—that is easy. But to be angry with the right person, to the right degree, at the right time, for the right purpose, and in the right way—this is not easy.” His point was that you had to be careful not to starve your kid because your husband ate the last cookie. You were supposed to ask yourself if one anger was just an easier way to be angry than the way you were angriest. Once I pondered it, the answer was clear as club soda: I wasn’t angry about the cancellation. I was angry with my lousy ex-boyfriend who didn’t know much about anything except venereal diseases and living in his mother’s basement. He was the one who deserved a furious phone call. In fact, the next time I saw the cancellation, I’d congratulate her on being a strong, ambitious woman with a 401K and retirement plan. She, at least, thought about the future. It was satisfying to realize that the world was a perfect sphere again.

Or at least it was for an hour. I put my leftovers in the refrigerator to eat for lunch the next day. I sat down to watch some reruns. But after a few laugh tracks, all I could do was sneak greasy takeout noodles one by one every few minutes. When I was a smoker, I used to crave cigarettes all the time. Since quitting, I’ve come to crave cigarettes and food all the time. So by the time I got to bed, there was no lunch for tomorrow, and I was pretty certain I needed to go up a jean size.

I thought about calling my mom and pops, but it was too late for old people to be awake. I thought of calling my ex-boyfriend, but the way I was feeling, I didn’t need to talk to him to feel awful anyway. So I called the number on the television and said I was interested in buying the all-in-one Garlic Pal, which could mince, slice, and deodorize.

“You won’t be sorry,” said Theodore, a man who sounded as though he was sleep-talking. Then I hung up when he asked for my credit card number.

A day later, the detectives came to the salon. They wanted to know when was the last time I’d spoken to Elena Czarinsky, JD and recent cancellation. The detective with the saggy cheeks sat down in one of the salon chairs, but the young one who looked so proud of his badge stood with his hands holding his belt. I got the feeling he was trying to look amused but also like he had enough of these cases under that holster of his that this was like slicing butter. “Her appointment book said she was supposed to see you for a cut on Saturday at 4 p.m.,” he said.

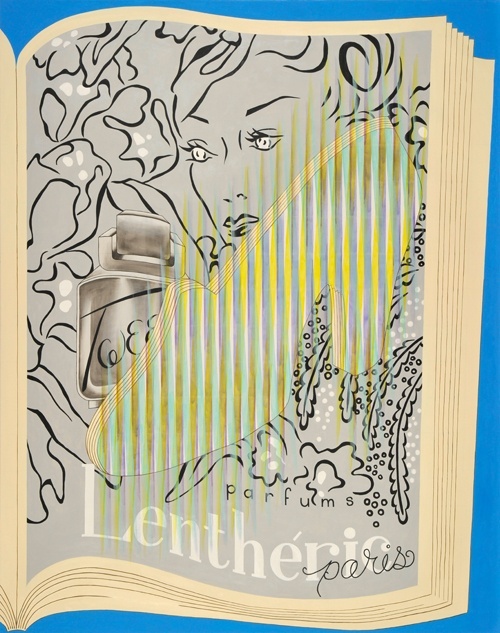

“Well, she didn’t, and you can ask those lesbian strippers if you need verification,” I said. Let’s just say I have less respect for the police than the real animal they’re often called. Pigs, it’s known, are intelligent. “What’s this about? Can’t you see I’m busy?” I pointed to the Color Sophisticates product line on the shelf. “Those colors don’t mix themselves.”

Saggy cleared his throat. “What this is about is that Elena Czarinsky can’t be accounted for since six on Friday.”

In my experience, it has usually been men overlooking the crimes of men that makes unsolved mysteries.

“She’s a strong, independent woman with a 401K,” I said. “What’s it to you?” My eleven o’clock was pretending to read an upside down magazine in the waiting area, and though I was trying to orate along the lines of Bill Clinton, the only Democrat my pop ever voted for, inside I was frail as his loopholes: “I did not have sexual relations with that woman.”

“She’s the prime suspect in the homicide of her husband, Oliver ‘Ollie’ Malone,” said the young one.

“Homicide?” I said. “How do you know it wasn’t him who did it?” In my experience, it has usually been men overlooking the crimes of men that makes unsolved mysteries. Put a woman cop in there who has the hell-topping fury that’s deserved when she’s scorned, and you can bet someone would pay.

“Read the papers, ma’am. That’s the official word.” Now my eleven o’clock wasn’t even pretending anymore.

“Well I don’t know where she is,” I said.

“And if you did?” the junior one asked.

“She got nothing.” This was the older one baiting. “She doesn’t know anything. Give it a rest.” There were some looks back and forth, some jack-o’-lantern grins meant to agitate me. I smiled right back and touched my two-fronts to indicate spinach stuck in the young one’s teeth.

“Well give us a call if you learn anything,” he said sulkily, pulling the greenery from his teeth. Then he handed me a card and the brass chiming bells smacked the glass door behind them.

The rest of the day I made a lot of mistakes and probably screwed up a bunch of girls’ social lives for the next six to eight weeks, at which point, I knew they wouldn’t come back for a trim. Slick salon chairs, adhesive mousses, noisy air: this was all it was. “My wedding is tomorrow!” one woman complained. “And now I’m bald in the front! I’m going to be bald in my wedding photographs!”

“True love is unconditional,” I said and pushed her out the door.

She began banging the glass. “This is supposed to be the best day of my life, and now it will be the worst!”

“Then you’re lucky!” I mouthed. Maybe I would’ve felt bad if she hadn’t come back fifteen minutes later, screamed “Nice braces!” then dumped a bottle of shampoo on the floor. Celeste had to wipe it up and we were slipping around, falling on our knees and bruising our bottoms, all afternoon.

During my lunch break, I thought about what I thought about Elena Czarinsky. Honestly, I’d never liked her much. She was one of those women who flashed her electronics around to remind everyone she had a real job where she was irreplaceable. She tipped with the generous lunacy of a woman who’s had to take her clothes off for a living. Once she told me she got off bad guys just to show she knew the law better than the next guy, and it wasn’t an apology. Actually, I could have hated the woman.

But then there was Margarita. She and Elena had been best girls since their days at Next Door. So there had to be something about this woman besides her tips.

At the end of the day, I waited for Celeste to leave. When I was certain she was blocks off, I got Margarita’s number from the Rolodex at the front desk. The first call there was no answer. The second call she picked up.

“Hello?”

“It’s Jolene, sugar.” I tried to speak calmly.

“Gracias a dios,” she said.

I’d never been to Margarita’s apartment before, though I did make her up for her wedding. It was a real nice up-do, teased in the front with a neat French twist in the back that blossomed at the crown of her head in curls I’d sewn with tiny pearls. A picture of this and her old good-for-nothing sat on a table right inside the entrance to her apartment, I noticed, when she opened the door. Her eyes looked like swollen beestings from crying, and there were glistening threads of snot clinging to the inner rim of her nostrils. It took a moment for her to keep the tears down long enough to speak, and I hovered at the threshold like a shy bride.

“Oh Joley, thank you for coming. I’ve been next to myself.” Margarita sometimes made these sayings mistakes when she was upset. It was one of her better qualities. Right after she separated from her husband, I only understood halfway for weeks. It was awful to take such pleasure in a person when she was in pain, but I couldn’t help it. It was odd to be invited into Margarita’s life this way, and it was wonderful. She began to hyperventilate or cry, and I waited until she stopped to answer.

“Where do you keep the hemorrhoid cream around here?” I said. “A touch of that and some cucumbers will take the puff right out of your eyelids.” I’d learned this trick in Hollywood. Stars and their help swear by it, but Margarita stared. I looked right back, and her eyeballs trembled liquidly. She’d lost a good hunk of weight this past year, and her sweatpants hung on her hollowly.

“I don’t care about my face right now,” she said. I didn’t either, but I’d wanted to fix something, anything. I looked at my feet, large and filthy things, big enough to belong to a man, then pressing my heels to the floor, fanned my toes out and in.

“It smells nice in here. Soapy or something.” There was something stuck to my shoe, and I bent down to rip it from the sole. “Cilantro?” The smell was sharp and green and clean. For a moment, there was the awful possibility that she’d ask me to leave.

“I’m sorry,” she said slowly. “I’m just a little—”

“No apologies,” I said quick as whip. “A lot of people don’t like the idea of rubbing anus ointment on their eyes.”

“Oh Joley,” Margarita said. “Thank God you’re always yourself!” Then she hugged me, and it was almost like having a sister. Through our t-shirts, her warm soft breasts squished velvetly against mine. She took my hand and led me inside.

The camera refocused on a neighbor who said the Czarinsky-Malones had always seemed like a normal happy couple, as though such a thing existed.

I didn’t feel like I needed to hear the story to know Elena was right, but already she was on the news. Apparently this husband of hers was one of those guys mothers tell children not to take candy from. I’d met the guy once before. I guess he was one of those handsome perverts. “I killed a mentally ill person, and he was my husband,” Elena told reporters on the eight o’clock news. “I killed a mentally ill person,” she said again before the camera refocused on a neighbor who said the Czarinsky-Malones had always seemed like a normal happy couple, as though such a thing existed.

“We spoke last week,” Margarita said quietly. “She said they were having problems. Not disasters! I would have done something.” I didn’t ask what she would have done, because I could tell Margarita already was trying not to cry. She was a giver. She’d give someone the hair off her head and had. Last year we made of a wig of probably eight years’ worth of her hair for her sick sister. Now she wanted to give Elena her innocence, and she couldn’t. There was a chessboard on the table and she spun a black queen between her fingers. “It was a crime of passion,” Margarita said finally. “The court will have to understand this. He was a dangerous sex fiend!” She stood up and then sat right back down. She moved a chess horse in a forward L and then angled backward. “Don’t you think?” she asked. “Don’t you think it will have to?” Purplish shadows hung beneath her eyes. She looked so beautiful and tired that I wanted to lie. “Don’t you?”

“Maybe,” I said.

“But justice?” Margarita said hopefully, grabbing my hands. “There must be justice, of course?” I shrugged. “What’s the sentence for it? Fifteen years? Twenty?”

“For a husband, maybe life,” I said.

“No!” she said.

“Maybe,” I said.

Margarita went to the kitchen to fix tea and a fruit platter. I could hear the slide of her blade against the wooden chopping block, and the bright metallic sound whined hopefully. The shrill kettle screamed with steam, and finally, she padded through the doorway between the kitchen and living room with her tray. The fruit was cut to look like giant pineapple smiles. I saw her fiddle in her pocket. Then she lit a joint and passed it.

“I don’t normally do this, but,” she said.

“Today isn’t normal,” I said to be gracious.

For a while, we sat in front of the television, smoking and staring at the news. The faces appeared strangely specific, both defined and far away. When I turned to Margarita, I couldn’t take my eyes off the pineapple juice droplets dribbling over her bottom lip. She was a messy eater, and when she dripped, her tongue roved all the way down her chin.

“Fifteen?” she said, again full of sudden hope.

“Maybe,” I said. In the corner beside the TV, I noticed a plant with waxy leaves stretching up out of a woven wooden basket. It looked too good to be real.

It was all so simple, I was sure. I could already see it now. If Elena became me, and I became no one, I could be everyone.

“Fifteen is still forever,” she said. Then she put her face in her hands.

What would it be to be loved like this? I didn’t know. I was certain I’d never been loved as large and hard. Probably I never would, nor would Elena again. But then, it was all so simple, I was sure. I could already see it now. If Elena became me, and I became no one, I could be everyone. I’d change my look a lot. There’d be a perm that wasn’t permanent like the name suggests, a brunette phase, a smart little pixie cut. Sometimes a man might ask me out on Monday and two days later ask me out again. He wouldn’t even know why he got left sitting alone in a restaurant on a Friday night, but I’d save myself a lot of heartache and moping to country songs. I’d start and end a new life every day, and for the first time, Margarita would love Joley like a real friend.

“What if she were me?” I said. Margarita turned in my direction and opened her eyes, slow as pouring honey.

“Excuse me?” She rubbed her mouth with the inside of her elbow.

“What if Elena posted bail, left the country for somewhere the law wouldn’t apply anymore, and pretended to be me? She could get on a plane. I’d give her my passport.”

“You’re a redhead,” she said. Her brown eyes went matte and dark.

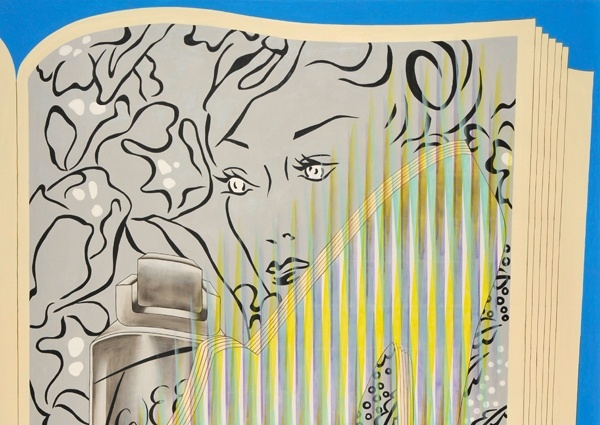

“Don’t tell me you haven’t seen the commercials now, Margie. Naturally Yours: Colour Sophisticates!”

“You’re naturally blonde?” She put down half a fruit slice.

“I’m a professional,” I said.

“I didn’t think I could laugh at a time like this,” she said.

I pointed out that she hadn’t.

For a while I thought she’d say something, but I thought I’d say something even more. I thought and thought, and neither happened. My mouth felt heavy, and the air in the room began to press on my chest. When it became obvious she wasn’t going to say anything, I pulled a brush out of my bag. With one hand, I gripped the dip in her shoulder where it met the neck, and with the other, got stroking. At first she started a bit, but after a few runs of the boar bristle down her scalp, I felt her settle back into me.

Her bottom was wedged in between two plush couch cushions, and I straddled her hips from behind with my thighs as I worked the knots out. Bracing her this way made the spinning room stay in place. “That’s it,” I said. “That’s all right now. That’s it.” Her entire head of hair was gathered in one of my fists, and I flicked the ends until I could glide my fingers through with ease. With the tips of my fingers, I dragged her lids closed gently, then skimming my hands over her cheekbones, worked my fingers in the fold behind her ears. When I slid down her neck, I could feel a drowsy pulse, and her breath caught a little. Then I squeezed my knees together and really got the brush rhythm going. A few times, she let out a series of little gasps. “That’s nice, sugar,” I said. “We’re getting there. That’s it. That’s it.” After a while, my palm went buttery with sweat, so I made the hard handle tight in my fist. She was getting silky, the rewards of my work pliant in my hand, and though I could hear my heavy breath, I just kept at an even tempo with the brush shaft up and down. Closer. We were getting closer. I can’t explain why, but my hands were vibrating, and I could feel the blood washing warmly through me. My eyes started sinking in the aqueous black gleam of her hair. It occurred to me that I could get lost in there and never care to be found again. Once, I remember my sister telling me about reincarnation. She said it was when you didn’t really die, just became an animal. This was what it had felt like: reincarnation. Or else it was just that something with a long, horrible history had fallen away. The hot, damp smell of the oils from Margarita’s scalp rose, and I was certain that this was what freedom felt like.

“Time to pee-pee,” Margarita said, standing up abruptly.

“That was amazing,” I said, the bright buzz still in my chest. But the room had already started slowly spinning away from me once more, and I could see her face exaggerated with awful bafflement. I guess I thought my luck was changing, but there’s this joke that goes, “Who can shave thirteen times a day and still have a beard?” The answer’s a barber.