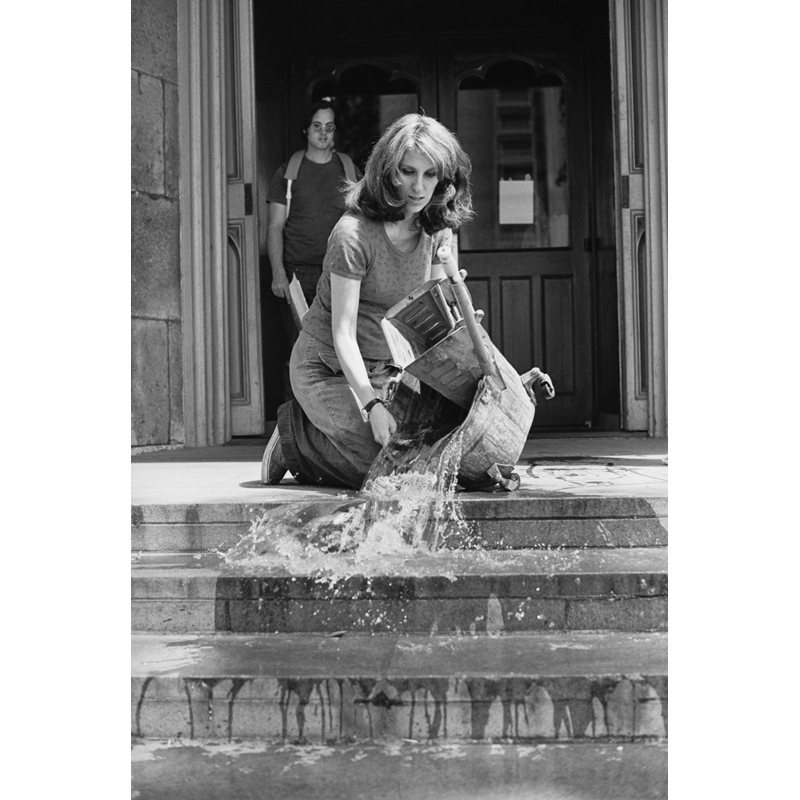

Mierle Ukeles, Hartford Wash: Washing, Tracks, Maintenance:Outside, 1973 performance at Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, CT, part of Maintenance Art Performance Series, 1973-74. Courtesy the artist

O

pen Engagement is an annual conference committed to examining how artists, institutions, and publics approach art and social practice. Co-presented by the Queens Museum and A Blade of Grass foundation, the three-day program sets out to expand the dialogue around the production and experience of socially engaged art. Founded in 2007 by artist and professor Jen Delos Reyes, this year’s theme is Life/Work: the rewards, penalties, drawbacks, and sacrifices that, although always personal, unite the creative class in myriad social, political, and economic ways.

This year’s keynote speakers, J. Morgan Puett and Mierle Laderman Ukeles, are veteran creators who leverage the everyday into art. Puett explores pedagogical structures, systems of labor, sociality, and ethics; her work is realized as beautiful clothing, raucous dinner parties, and interior design. At her Pennsylvania home and artist colony, Mildred’s Lane, no household item is ugly or left to languish, no chore is tedious or unpleasant. Her life is a consistently evolving tableau of interdisciplinary art-making. The Mildred Complex(ity) is the Narrowsburg, NY, location of this enterprise, an office/storefront/project space.

Ukeles has a more urban existence; she reframes labor as potent work. In 1969, after struggling with the demands of young motherhood and her creative calling, she wrote Manifesto for Maintenance Art, redefining her daily routine of housework and childcare as what they are: vitally important, life-giving activities. She wrote, “keep the dust off the pure individual creation; preserve the new; sustain the change; protect progress; defend and prolong the advance; renew the excitement; repeat the flight; show your work—show it again / keep the contemporaryartmuseum groovy / keep the home fires burning.” As the artist-in-residence of the New York Sanitation Department for over three decades (and the only person to ever hold this position), her performances and projects focus on environmental, ecological, and sustainable issues. Her first work there was “Touch Sanitation” (1977-80), where she shook the hands of 8,500 sanitation employees, telling them, “Thank you for keeping New York City alive,” bringing attention to the frequently maligned yet invaluable city system.

With an extensive program, the conference will take place at the Queens Museum and various other locations around New York, and will present a series of open houses that will showcase (among others) Creative Time, Aperture, Flux Factory, and MoMA Studios, panels, lectures, and presentations on topics as varied as bike repair, Tania Bruguera’s Immigrant Movement International project, and the city’s Watershed Relief Map. Workshops such as “Curating for Socially Engaged Art” and “Introduction to Cultural and Community Organizing” will be held. On Friday, May 18, at 5pm, “Writing for Socially Engaged Art”—presented by Guernica’s own Chelsea Haines—will bring together artists, art critics, and curators to tackle the question of writing about art that doesn’t immediately look like art.

A blog leading up to the events presents interviews with a hundred artists to kickstart the dialogue. Mark McFarland was asked, “What does social practice offer white artists?” To Shannon Jackson: “How do we know if social practice is being transformational?” To Jon Rubin: “How do we move on beyond navel gazing, choose a question to answer and answer it in depth?”

The following conversation between Puett and Ukeles, moderated by Delos Reyes, is condensed from a version that will appear in the conference catalogue.

Was there a particular moment in your practice when you made a conscious decision to merge your life and your work as an artist?

J. Morgan Puett: The conscious decision was realized in graduate school. Once out of school, engaged in filming-dwelling-clothing-researching projects, I found that making clothes for people gave me great pleasure. Somewhere along that path I realized that was a way to survive as an artist. Although, in learning the industries, I forgot that pleasure for a time while struggling with capitalism. I thought of my work in the rag trade as a series of conceptual storefront projects; then later I created a long series of research projects and art installations for institutions that were about those (disturbing) experiences in the fashion industry. It was all extremely important to the development of the ideas and methods that permeate everything I do now.

The artist must survive. It is art that must change.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles: I lusted for the freedoms expressed in the work of my art heroes: Jackson Pollock, Marcel Duchamp, Mark Rothko. I wanted that life of the autonomous artist, pushing into the unknown, creating the new. I struggled for many years. Then Jack Ukeles and I had a baby in 1968. My teacher in grad school, seeing my pregnant belly, said—despite my being his best student—“Well, I guess you can’t be an artist.” This gurgling baby was depending on my constant maintenance. I found that my art heroes didn’t change diapers. I tried to split my life in two: half the mother/maintenance worker, and half the artist. Why hadn’t my education prepared me for this? I was in a full crisis. Then, after one and a half years of twirling, an epiphany! If I am the boss of my freedom, if I have this power, then I call maintenance, art; I call necessity, freedom. I can collide these two poles, crash them together. In a quiet rage, in October 1969, I sat down and wrote the Manifesto for Maintenance Art, 1969! I named Maintenance as Art. Why? Because I say so. The artist must survive. It is art that must change.

What are the advantages and challenges of having a practice that is so entwined with aspects of daily living?

Mierle Laderman Ukeles: The advantages: my insight in 1969 enabled me to go into the dark gap in Western culture where those who serve and support are not inside the picture. By which I mean: the picture of power, of culture, inhabited by the powerful and the cultured—those who are meant to be seen. Well, that’s not how democratic culture is supposed to work. I was seething. Why was I so pissed off? Because my education promised me that I belonged to the entitled; it was supposed to be me in the picture. And here I was stuck changing diapers. People had stopped asking me questions, as if they knew all about me, and it wasn’t very interesting. But with my epiphany, a door opened. I could have a chance to become connected to most of the people in the world who spend most of their lives surviving and enabling life to continue, most of whom the Western Culture hadn’t seen, didn’t know how to see, how to acknowledge, honor, or respect.

The challenges: So how do I eat? Keeping going as an artist has been difficult, and never gets easier. The philosophy and conceptual aspects are so much a part of me—that’s not hard. Most of all what keeps me going has been Jack Ukeles, my soulmate who believes in me as I believe in him. Everyone and everything that keeps life going feeds me as an artist and person.

J. Morgan Puett: My life as a traditional artist never ceased. Those tools are just more complexly integrated into my existence. I started the fashion business fresh out of graduate art school to have an income. Now I have created a new contemporary art complex and school of sorts, the Mildred’s Lane Project. It does not support me financially, but it does enrich me intellectually and allows for me to share with my friends. I feel the need to make every aspect of living meaningful, artful. Life as a practice; being as the practice.

Many art schools do not teach the skills and approaches necessary to creating and supporting practices like yours. What assignments would you give students to begin to build a foundation for these ways of working?

Mierle Laderman Ukeles: First: The artist needs to trust her/himself. The art grows out of this trust, which goes to the core of the person. The artist needs to understand her/his metaphysical state of being free, and to cherish freedom.

Second: Freedom education. Who has power, who does not, and why. Open to the delightful understanding that all in the world is open to you.

Third: Strategy. How to know if what you are doing is what you are doing. And, are there different ways to move? Are you missing central items and key subtle items?

Fourth: Learning skills. Skill education can be gendered in a hidden way. I was too ideological in school and refused to learn traditional skills if they didn’t fit directly into what I was crazy about at the time. It helps to learn how to handle a huge variety of materials, ideas, and social constructions.

Fifth: Integration education. Practice putting everything together into a perceptible whole. If it doesn’t make you sick, practice putting it together in different ways. A goal is so people can perceive the whole of what you are doing, even if the parts are very different from each other.

Sixth: Flexibility. What is the difference between being in school, and being done with school? Think about it as a place to practice stuff and try lots of things.

J. Morgan Puett: Collaboration is an essential practice in the 21st century; we can’t make change happen alone. Open a storefront practice instead of a studio. Be in the world. Be of the world. Be for the world in any way you can.