Once upon a time it was a commonplace that Israel’s founding entailed the dispossession of the indigenous population. After World War II, Hannah Arendt observed matter-of-factly, “it turned out that the Jewish question, which was considered the only insoluble one, was indeed solved—namely by means of a colonized and then conquered territory…. [T]he solution of the Jewish question merely produced a new category of refugees, the Arabs.”

Nonetheless, Israel’s public relations apparatus managed through repetition to instill the myth that this “new category of refugees” was not the inexorable outcome of colonization and conquest, but instead the result of a circumstantial and incidental event for which Israel bore no culpability. The official Zionist tale alleged that via radio broadcasts, and despite Israeli pleas that the Palestinian population remain in place, neighboring Arab states had instructed Palestinians to flee in order to clear the field for invading Arab armies. Although researchers had already disproved this claim by the early 1960s, it required the industry and pedigree of an Israeli historian to lay it to rest.

In 1986, scholarly US journals published a pair of articles by Israeli historian Benny Morris chronicling the ethnic cleansing of Palestine. In one of them Morris graphically recalled the order given by Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion in July 1948 to expel Lydda’s 30,000 Palestinian inhabitants, the “large scale massacre” of upward of 250 Palestinians in Lydda that precipitated the expulsion, and the ensuing death march in which scores more Palestinians perished. The next year Morris reported this brutal episode and many others in his landmark study, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947-1949.

Israel’s founding entailed no wrong because no native population existed on which to inflict a wrong.

The principal organs of American Jewish opinion ignored at the time unwelcome tidings such as Morris’s. Commentary, at the right end of the political spectrum, and The New Republic, at the center, promulgated an “immaculate conception” version of Zionism, according to which Palestine had been literally empty on the eve of Zionist colonization; Israel’s founding entailed no wrong because no native population existed on which to inflict a wrong. The Nation magazine, at the left end of the spectrum, was scarcely better, and arguably worse. In 1989 it published an eyewitness account of the events in Lydda by an Israeli “peacenik.” He purported that “we never really conquered Lydda. Lydda, to put it simply, fled” [emphasis in original]; “From the jeeps, soldiers fired indiscriminately in all directions. Here they smashed a windowpane, there they killed a chicken”; “there was really no city to conquer. The whole place, except for [future Palestinian leader] George Habash and his sister, and a few others, was empty.”

One might wonder why The Nation would publish an article about a non-event. In fact, “the story I am telling here really begins,” according to the peacenik, “at night, [when] those of us who couldn’t restrain ourselves would go into the prison compounds to fuck Arab women.” Actually, to rape, but why get hung up on nuances in a story so irresistibly titillating, of an Israeli Jew who, unlike his scrawny American counterparts, gets to copulate with macho abandon? And anyhow, his enviously awestruck American editors and readers could rationalize, as the Israeli did, that “those who couldn’t restrain themselves did what they thought the Arabs would have done to them had they won the war.” Just as, if men were women, and women men; then women would rape men; ergo, it’s okay if men rape women. None of The Nation’s house feminists, who periodically erupted in politically correct indignation at the vaguest hint of sexism in the magazine’s pages, objected to the Israeli fucker’s logic.

Such was the impoverished historical and moral sensibility of American Zionism in its heyday, and even at its enlightened extreme.

But in the three decades that have since elapsed, the unsparing findings of serious scholarship have, willy-nilly, seeped into the consciousness of American Jews. They now know too much: the unvarnished truths displacing the old clichés conflict at all points with their liberal ethos, causing a crisis of Zionist faith. Like the tobacco industry after the Surgeon General’s warning in the 1960s, the formidable challenge confronting Zionist true believers is to repackage the old product such that it still sells despite its disquieting contents.

Judging by the response to Israeli journalist Ari Shavit’s book, My Promised Land: The Triumph and Tragedy of Israel, published in the US in late 2013, Zionism might yet be (or, be made) a marketable commodity among Jews. Prominent figures in the Jewish establishment across the political spectrum—from the Anti-Defamation League’s Abraham Foxman to The Atlantic’s Jeffrey Goldberg to the New York Times’s Thomas Friedman to The New Yorker’s David Remnick—have weighed in with effusive praise. “This is the least tendentious book about Israel I have ever read,” The New Republic’s Leon Wieseltier enthused on the front page of the New York Times Book Review. “It is a Zionist book unblinkered by Zionism…. There is love in My Promised Land, but there is no propaganda.” Coming from this arch propagandist, who formerly retailed the Palestine-was-empty thesis, such an endorsement does not carry conviction.

My Promised Land does acknowledge many uncomfortable facts about Israeli history and society but, besides love (indeed, a superabundance of it), the book is also shot through with exculpatory propaganda and contradictions. The question is whether Israel can yet again inspire American Jews after Shavit’s inspired repackaging of no-longer-evadable facts. The answer is probably no. It both recycles too many shattered myths and confirms too many ugly truths to exhilarate anyone outside the depleting (and aging) ranks of Zion’s worshippers.

The discursive crux of My Promised Land comes in the chapter recounting the ethnic cleansing of Lydda. Shavit’s telling of how “Zionism obliterates the city of Lydda” mostly echoes Benny Morris’s critical findings, from which he then proceeds to extrapolate a bigger two-fold truth, one factual, the other a value judgment. First, what happened in Lydda had to happen if Zionism was to triumph:

And second, what happened to Lydda, albeit a “tragedy,” “human catastrophe,” and grounds to be “horrified,” should have happened because of the greater (Jewish) good that ensued:

Insofar as Shavit has put forth what, in the wake of a deluge of damning scholarly revelations, is now being touted as Zionism’s best defense, it merits parsing his arguments, both on this point and kindred ones, to see just how well they hold up. If they fall, this would suggest that, short of an existential threat to Israel, American Jewry’s growing estrangement from it is irreversible.

Shavit is not altogether consistent on why “If Zionism was to be, Lydda could not be. If Lydda was to be, Zionism could not be.” At times he suggests a contingent explanation in which Zionists come off as reacting defensively to events outside their control and therefore ultimately blameless. In this rendering, the Zionists came to Palestine bearing benign intentions—indeed, “while some Palestinians do suffer, many of them benefit considerably as Zionism advances…. Jewish capital, Jewish technology, and Jewish medicine are a blessing to the native population, bringing progress to desperate Palestinian communities.” But then, beginning in the mid-1930s, just as “[t]he two peoples of the land are working side by side,” Palestinians inexplicably and irrationally explode in murderous rage, as an Islamic fundamentalist preacher’s call for an anti-Semitic jihad resonates among them. It was only “[f]rom this moment on”—i.e., in the face of Palestinian violence, and after the British Peel Commission recommended (1937) partitioning Palestine and “transferring” the Palestinians out of the prospective Jewish state—that the Zionist movement began to advocate expulsion. Thus Shavit writes: “What was absolute heresy when Zionism was launched became common opinion when Zionism confronted a rival national movement face-to-face.”

But at other points, Shavit posits that a significant Arab presence in Palestine conflicted with the very essence of Zionism, as in, “From the very beginning there was a substantial contradiction between Zionism and Lydda.” In fact, this thesis comes much closer to the truth: if an ethnic Jewish state was ever to arise, Palestine could not be. “Transfer was inevitable and inbuilt in Zionism,” Benny Morris observes,

For one disposed, as Shavit clearly is, to justify Israel’s creation at the expense of the indigenous population, the question then boils down to: How does one excuse ethnic cleansing?

Hence, in the sequence of cause and effect, it was not Palestinian violence that induced the Zionist movement to advocate expulsion but, inversely, the intent of the Zionist movement from its inception to ethnically cleanse Palestine that provoked Palestinian violence. As Morris puts it, “The fear of territorial displacement and dispossession”—a perfectly rational fear, as he demonstrates—“was to be the chief motor of Arab antagonism to Zionism.” And as Shavit surely knows, already at the birth of Zionism, the idea of expulsion, far from being an “absolute heresy,” was discreetly advocated by, among others, founding father Theodor Herzl.

For one disposed, as Shavit clearly is, to justify Israel’s creation at the expense of the indigenous population, the question then boils down to: How does one excuse ethnic cleansing? This is quite the challenge for a self-described champion of human rights. To begin with, Shavit reduces it to manageable proportions by contextualizing his response in a narrative wherein the expulsion of Palestine’s indigenous population is just not that big a deal. If one didn’t know better, between the natives, on the one hand, and the pioneers determined to replace them, on the other, one would surely root—as in pre-enlightened US accounts of the conquest of the West—for the pioneers, as bearers of Progress in an otherwise virgin land. Although Shavit waxes perplexed at how the first Zionist settlers could have blinded themselves to the Arabs’ presence in Palestine, his supposedly propaganda-free story just barely concedes their existence. In Shavit’s telling, Palestine might not have been a “land without a people,” but it was also not much more than a land with a few scattered and sickly persons, who obstructed the rugged agents of Jewish renewal. “I am no judge, I am an observer,” Shavit declares, but, alas, he observes through the judgmental lens of an unreconstructed European imperialist. Here’s a sampling of Shavit’s juxtapositions, packed into the book’s first 70 pages:

| NATIVE | PIONEER |

|

[Visitors] notice the infected eyes of the village women, the scrawny children. And the hustling, the noise, the filth. Once again [visitors] are confronted with the misery of the Orient: dark, crooked alleyways, filthy markets, hungry masses…. Young boys look like old men. Disease and despair are everywhere. This desolate land is where [Jews] will find refuge. Scattered among the fields were deadly marshes in which Anopheles mosquitoes bred, infecting most of the local Palestinians with malaria. [N]ative life meandered as it had for hundreds of years. Still, death was in the air. It lurked low in the poison-green marshes of Palestine. The waters flow slowly…, as they have for a thousand years. Every so often, water trickles into the ditches that the peasants dig in order to nourish their meager crops. But these waters create the boggy marshes from which rise the poisonous vapors of malaria…. Everything here…is idle—the torpor of an ancient land deep in ancient slumber. |

In the harsh conditions of this remote Ottoman province, Dr. Yoffe is the champion of progress. His mission is to heal both his patients and his people. Mikveh Yisrael is an oasis of progress. Its fine staff trains the young Jews of Palestine to toil the land in modern ways…. The French-style agriculture it teaches will eventually spread throughout Palestine and make its deserts bloom. [Visitors] are relieved to find [in a Zionist colony] such architecture and such a household and such fine food in this backwater. [The pioneers] will drain the thousand-year-old marshes and muck and malarial scourge and clear the valley for progress. Acre after acre, the marshes give way to fertile fields. Zionist planning, Zionist know-how, and Zionist labor push back the swamps that have cursed the valley for centuries. Malaria is on a dramatic decline. The gray, arid wasteland has given way to a rich habitat of flora and fauna…. What the orange grower sees all around him is man-made nature. |

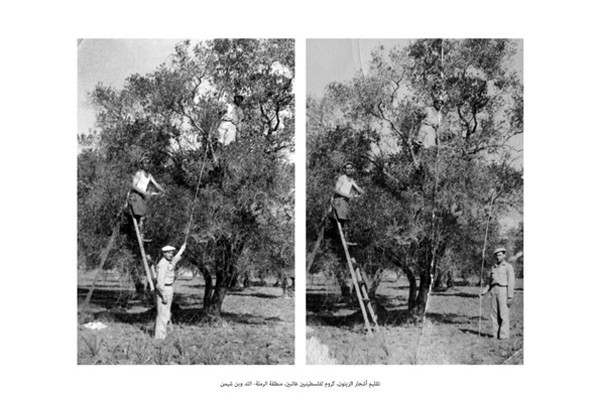

In Shavit’s distillation, even the sheep of these pathetic Palestinians are “gaunt.” Meanwhile, the Zionist pioneers manage, while making the desert bloom, also to peruse Marx, Dostoyevsky, and Kropotkin, revel in Beethoven, Bach, and Mendelssohn, and are even green-friendly, as they adopt a “humane and environmentally friendly socialism.” So determined is Shavit to prove the natives’ torpid ineptitude and so carried away does he get in his paeans to the resourceful Jewish pioneers that he lapses into bizarre non sequiturs. A chapter begins, “Oranges had been Palestine’s trademark for centuries.” But by chapter’s end, one of Shavit’s protagonists “wonders about the mysterious bond between Jews and oranges. Both arrived in Palestine around the same time…. Neither Jews nor oranges could have prospered if the British had not ruled over Palestine.” In fact, already in the mid-nineteenth century Palestine’s indigenous population practiced “intensive planting” of orange orchards, and “from 1880 until the outbreak of World War I, the acreage for citrus orchards more than quadrupled” while “the number of cases of fruit shipped through Jaffa’s port increased more than thirtyfold in the half century before the war, due to the increased acreage and partly as a result of new, more efficient agricultural techniques” (Baruch Kimmerling and Joel S. Migdal).

Moreover Shavit cannot resist a single cliché, no matter how insipid:

Not since Elie Wiesel set his pen to paper has such execrable prose been wrought.

Shavit has contrived a caricature reminiscent of now largely discredited apologetics from the epoch of Western colonialism.

Of course, the tale would not be complete without Shavit’s Oriental Wisdom 101 insight, channeled through a Zionist citrus farmer “who knows the Arabs, their tongue, and their ways”: “[T]he trick with the Arabs was to honor and be honored, to give respect and demand respect.” A strict yet benevolent disciplinarian, the orange grower “provides medical and financial assistance. The Arab villagers working in the grove respect [him]. They admire his knowledge, they appreciate his fairness, they dread his master’s authority…. They are committed to their work and devoted to their master. And yet the orange grower knows that one day, one day.” But, rest assured, the grower can always count on “[o]ne Arab [who] is different from the others,” named—could it be otherwise?—“Abed,” who “is totally loyal and enjoys the owner’s total trust.” One waits with bated breath for the Shavit sequel, Uncle Abed’s Hut.

It is not to begrudge the Zionist settlers the magnitude of their sacrifices and achievements, which impressed many progressive foreign observers at the time, even on the anti-imperialist left, to recognize that Shavit has contrived a caricature reminiscent of now largely discredited apologetics from the epoch of Western colonialism. If My Promised Land reads a notch better than Leon Uris’s Exodus, it is only because of the book’s knowing detail, and if it has triggered paroxysms of ecstasy among Zionist true believers, it is no doubt because they long for a return to the glory days when Exodus made Jews surge with wonder and pride. But those with a liberal sensibility—which means most American Jews—will surely recoil, if only from politically correct unease, at this moth-eaten conjuring of benighted natives inhabiting a wasteland who, wise Providence or inexorable Progress has decreed, must retreat before enterprising Europeans determined to transform malarial marshes into a citadel of Science and Civilization.

When he touts Israel’s innumerable breakthroughs in science, technology, and the arts, Shavit seemingly also lends retrospective justification to Palestinian dispossession. The tacit message is that Palestinians, if left to their own devices, would have produced just another destitute, dreary, and despotic Arab state, while the world would have been deprived of Israel’s high-tech industries, cutting-edge inventions, and flourishing cultural landscape. The argument is not a new one. In the US’s triumphant moment, Theodore Roosevelt averred in his classic The Winning of the West:

It is impossible to disprove this logic in terms of logic. It is arguable that, had the Europeans not conquered North America, it would still be dotted with teepees, and had Jews not entrenched themselves in Palestine, it would still be comprised of mud huts. The fact remains, however, that even an exiguous notion of human rights and international law—the cornerstones of a liberal outlook, to which so many American Jews subscribe—cannot be reconciled with such a moral calculus. The Shavit mindset is a throwback to another epoch that has been superseded in the West (in enlightened liberal precincts, at any rate, and if only as a protocol, not rooted belief) by one less confident of its civilizational superiority and more tolerant of cultural diversity. Nowadays, it’s just not good form to cheer giant bulldozers as they demolish ramshackle dwellings that are home to an indigenous people, forcibly relocated in order to make way for Progress, even if the people are offered accommodations elsewhere (which, it need be remembered, the Palestinians were not) in ultra-modern high-rises.

To justify the injustice inflicted on Palestine’s indigenous population, Shavit formally invokes the conventional Zionist arguments of greater need and higher justice: were it not for Israel’s founding, Jews would have disappeared both spiritually—because of assimilation—and physically—because of anti-Semitism.

When Shavit asserts that, if not for Israel’s founding, “I would not have been born,” and that it “enables my people, myself, my daughter, and my sons to live,” he in part actually intends, “I would not have been born as a Jew,” and it “enables my people, myself, my daughter, and my sons to live as Jews.” Hailing as he does from a distinguished line of British Jews, Shavit speculates that had his family not settled in Israel, he would today probably be an Oxford don. The problem, as he lays it out, is that, because of unprecedented worldly success, non-Orthodox Jews in the UK and everywhere else in the Western world are assimilating, intermarrying, and consequently as a people inexorably disappearing:

Valid as Shavit’s premises might be, it still defies logic, not to speak of justice, why Palestinians should have paid the, indeed any, price, to reverse the effects of a deliberate and altogether voluntarily option Jews themselves elected. If it would be wrong, and no doubt an avowedly enlightened secularist such as Shavit would think it wrong, to impose external constraints on Jews—residency, dietary, and personal status laws—in order to preserve their peoplehood, then it must be all the more wrong to use force majeure against an exogenous party in order to preserve Jewish peoplehood.

One would be hard-pressed nowadays to find anything Jewish in secular Israeli culture, and Shavit doesn’t even try.

The ultimate irony is that the Israel that Shavit loves and lauds is not recognizably Jewish. The Zionist movement’s seminal years witnessed an ideological clash, the principals of which were Herzl, who conceived a state comprised mostly of Jews but cast in the mold of what was highest and best in European culture, and Ahad Ha’am, who envisaged in Palestine a spiritual center infused with reinvigorated Jewish values. To judge by Shavit’s account of the contemporary Israeli scene (or, at any rate, the part of it that he embraces), Ahad Ha’am’s vision clearly lost out. It might be true, as Shavit purports, that in the course of Zionist colonization and Israel’s founding years, Jews created a secular “Hebrew culture” and “Hebrew identity.” Still, it’s difficult to make out what was distinctively Jewish, except for revival of the Hebrew language (to which Shavit seemingly attaches slight importance), about Israel’s collective Spartan existence back then—which, although according to Shavit it “sanctified the Bible,” had more in common with Bolshevism than the Bible. He himself acknowledges that this Hebrew identity “detached Israelis from the Diaspora, it cut off their Jewish roots, and it left them with no tradition or cultural continuity…. Lost were the depths and riches of the Jewish soul.”

In any event, one would be hard-pressed nowadays to find anything Jewish in secular Israeli culture, and Shavit doesn’t even try. Quite the opposite. He devotes a cheesy chapter of Time Out-like prose to boasting of Israel’s torrid nightlife (“The word is out that Tel Aviv is hot. Very hot”) and no-holds-barred gay life (“the straights now envy the gays,” “it’s the gays who are leading now”), the anthem of which is, “Forget the Zionist crap. Forget the Jewish bullshit. It’s party time all the time.” His book’s only points of comparative reference and ranking are the fashionable districts of Western metropolises: “Tel Aviv is now no less exciting than New York,” “a music scene…that rivals those of London, Amsterdam, or Paris,” “[N]o one ever thought [Sheinkin Street] would become Tel Aviv’s SoHo,” “Allenby 58 is perhaps the fifth most important club in the world…. DJs and drag queens from all over Europe want to come here…. Allenby 58 is for 1990s Tel Aviv what Studio 54 was for 1970s Manhattan,” “at Hauman 17, the outcome is a burst of energy unlike anything seen in London, Paris, or New York,” “Tel Aviv’s liberal and creative culture is just like New York’s,” “Before me is an Israeli Central Park on the shores of the Mediterranean, a Hampstead Heath in the Middle East.” Contrariwise, Shavit repeatedly expresses disdain for Orthodox Jews (and Palestinian Israelis) as a brake on Israeli society and economy.

For all anyone knows or cares, Israel and Israelis might be, as Shavit proclaims, “astonishing,” “a powerhouse of vitality, creativity, and sensuality,” “innovative, seductive, and energetic,” “awesome,” “fascinating, vibrant,” “extraordinary…absolutely unique,” “exceptionally quick, creative, and audacious…sexy even in the way they work,” “hardworking and tireless,” “one of the most nimble economies in the West…an extraordinary economic accomplishment,” “truly phenomenal…astounding…a unique entrepreneurial spirit…a powerhouse of technological ingenuity…a hub of prosperity,” a “mind-boggling success,” “something quite incredible…extraordinary…authentic and direct and warm and genuine and sexy…exceptional…remarkable,” “creative and passionate and frenzied,” “phenomenal…epic.” But, as distilled through the secular values he prizes, Israel is also just another narcissistic Western consumer society. Indeed, consider Shavit’s own description of the “typical Jewish Israeli city of the third millennium”:

A “vibrant Israeli culture”? Perhaps. A vibrant Jewish culture? No. The most convincing witness is once again Shavit himself: “In the last third of the twentieth century, Hebrew identity was dulled. In the early years of the twenty-first century, it seems to have disintegrated…. The Israeliness that was once here is not really here anymore. The Hebrew culture…is gone.”

The only thing Jewish about Shavit’s Israel is its demography. Shavit loves Israel not because it is Jewish but because those who created it are Jews. His is an apotheosis of biological superiority, not cultural uniqueness. Hence, the book’s paeans to Israel’s “outstanding fertility rate,” and its designating the “concentration” of Jews as “the essence of Israel.” It is also why wholly assimilated, on-the-make American Jews—the Alan Dershowitzes, Norman Podhoretzes, and Martin Peretzes—came to embrace Israel: not because it was distinctively Jewish, but because it was distinctively not Jewish. It confirmed that Jews stood in the front rank of Western civilization. Jews had beaten the goyim at their own game, even—especially—in killing non-Westerners. In any event, if the raison d’être of Israel’s founding, and its justification for dispossessing Palestinians, was so that Shavit could live a Jewish “inner life,” he might just as well have stayed in England and married a shiksa.

When he declares that, if not for Israel’s founding, “my people, myself, my daughter, and my sons” would not be alive today, Shavit also means it literally. The embryonic Jewish state provided in his telling a safe port of entry during the Nazi holocaust, while since 1948 Israel has offered sanctuary from the ever-latent potential for another outburst of lethal anti-Semitism. The race against time figures as a red thread running through Shavit’s depiction of the Zionist conquest of Palestine. Zionist leaders supposedly anticipated, and acted in the foreknowledge of, the destruction of European Jewry. Thus we read: “[T]he Herzl Zionists see…the coming extinction of the Jews”; “There is hardly any time left. In only twenty years, European Jewry will be wiped out”; “[Labor Zionist leader Yitzhak] Tabenkin…believes…the Jewish people are heading for disaster. Twenty years before the Holocaust he feels and breathes the Holocaust daily”; “There is a feeling not only of success but of justice…. Europe is becoming a death trap…. Only a Jewish state in Palestine can save the lives of the millions who are about to die. In 1935, Zionist justice is an absolute universal justice that cannot be refuted…. The racist laws of Nuremberg prove Herzl right…: the great avalanche had begun: European Jewry is about to be decimated.” In effect, the fear of a Nazi holocaust serves, in Shavit’s account, as a moral alibi for Palestine’s ethnic cleansing: if the Zionist movement rode roughshod over the indigenous population, it was only in the hope of averting a far greater crime against the Jews in Europe.

It is a staple of Israeli historiography that the Zionist movement acted with a ruthless urgency born of its unique insight into the impending doom. The constant repetition, however, does not make it true. Zionist ideologues disputed the liberal piety that Europe would eventually accommodate the Jews in its midst. The point is moot. What would have happened to Europe’s Jews had Nazism not come along cannot be known. The fact that Jews in postwar Europe have managed to gain acceptance (and much more) doesn’t disprove the pessimistic Zionist prognosis. Hitler did after all quantitatively “solve” Europe’s “Jewish question,” while Holocaust guilt might partly account for Europe’s postwar welcoming. Possibly the Zionists were correct that Europe had—in the metaphor of Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann—a “saturation point” for Jews beyond which it couldn’t dissolve them and consequently would “react against them.” But it is a fiction that Zionists predicted the Nazi holocaust, and acted as ruthlessly as they did in its backward shadow. The Zionist movement did not produce first-rank thinkers, let alone ones gifted with prophetic powers. Herzl, for example, posited that, whereas anti-Semitism would continuously disturb Europe’s social order, it would not reach the point of criminally violating it: “it will be hot enough to push the Jews out, but, in a basically liberal world, it can never break the ultimate bonds of decency” (Arthur Hertzberg).

Still, if Zionists did not foretell the Nazi holocaust, it did happen. Does this indelible, irreducible fact vindicate Zionism and concomitantly justify Palestine’s ethnic cleansing? Cool reflection suggests not. Had a Jewish state existed in Palestine before or during the Nazi holocaust, it could not have provided an answer to a crime of such magnitude. More Jewish lives might have been saved, but the sanguinary balance sheet would not have been substantially altered. Indeed, it was only a historical fluke, as Shavit himself acknowledges, that any Jews survived in Palestine. If the Wehrmacht had not been defeated by the Allies at El Alamein, Jews in Palestine would have suffered a fate not unlike Jews in the Warsaw Ghetto.

It might nonetheless be concluded that, although a Jewish state did not offer an answer to it, still, the Nazi hecatomb did validate the need for a Jewish safe haven: when push came to shove, Jews could not count on anyone except themselves to give sanctuary. “Past experience, particularly during the Second World War,” Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko memorably told the UN General Assembly in 1947 during the debate on Palestine’s fate,

Irreproachable as it surely is, this plea on behalf of a Jewish refuge cannot be said to sanction Palestine’s ethnic cleansing, which, according to Shavit, premised Israel’s creation—“If Zionism was to be, Lydda could not be.” Although Gromyko’s first preference was the establishment in Palestine of “an independent, dual, democratic, homogeneous Arab-Jewish State…based on equality of rights for the Jewish and Arab populations,” he was prepared to countenance, if such an arrangement proved unworkable, the partition of Palestine “into two independent autonomous States, one Jewish and one Arab.” But neither the Soviet Union, nor any other state that later signed onto the Partition Resolution, sanctioned the erasure of not only the indigenous population’s rights but also their physical presence in the prospective Jewish state. On the contrary, the Partition Resolution explicitly stipulated that the Jewish (like the Arab) state must guarantee “all persons equal and non-discriminatory rights in civil, political, economic, and religious matters,” and prohibited “discrimination of any kind…on the ground of race, religion, language or sex.”

To judge by Shavit’s own account, the physical safety of Jews would probably have been better secured if a Jewish state had not come into being.

The claim that the Nazi holocaust justifies Israel’s creation and the resulting dispossession of Palestinians proves yet more problematic in light of Shavit’s depiction of subsequent history. If the Jewish state’s raison d’être was to avert another Nazi holocaust, this purpose would appear to be defeated by the fact that, according to him, Israel is daily encumbered by fear of, and its survival has repeatedly been thrown in jeopardy by, a “second Holocaust.” “For as long as I can remember,” My Promised Land begins, “I remember fear.” From there on, until its last pages, the book comprises a litany of external perils endangering Israel’s population: “Israel is the only nation in the West that is existentially threatened”; “The Jewish state is a frontier oasis surrounded by a desert of threat”; “In May 1967…[s]ome feared a second Holocaust”; “Hundreds or thousands of Israeli civilians might be killed as every site and every home in the Jewish state will be within reach of the rockets of those enraged by Israel’s very existence”; “[O]n June 7, 1981…mission impossible was accomplished. One meticulous minute over the target [Iraq’s nuclear reactor] had removed the threat of a second Holocaust”; “[O]n September 5, 2007, four F-16 bombers took off for the Syrian nuclear reactor…. Once again, one meticulous moment hovering over the target removed the threat of a second Holocaust”; “Iran is not a Netanyahu bogeyman; it is a real existential threat”; “We dwell under the looming shadow of a smoking volcano.” The climactic image of Shavit’s book portrays “concentric circles of threat closing in on the Jewish state,” including the “Islamic circle” (“A giant circle of a billion and a half Muslims surrounds the Jewish state and threatens its future”), an “Arab circle” (“A wide circle of 370 million Arabs surrounds the Zionist state and threatens its very existence”), and a “Palestinian circle” (“An inner circle of ten million Palestinians threatens Israel’s very existence”)—and what’s yet more ominous, “In recent years, the three circles of threat have merged…. [P]ressure is mounting on Israel’s iron wall. An Iranian nuclear bomb, a new wave of Arab hostility, or a Palestinian crisis might bring it down…. [I]t is clear that we are approaching a critical test.”

Even allowing for Shavit’s hyperbole, fearmongering, and sheer propaganda, it would be hard to disagree that, next to the dangers confronting Israel, those hanging over the other constituents of world Jewry pale by comparison. To judge by Shavit’s own account, then, the physical safety of Jews would probably have been better secured if a Jewish state had not come into being. It cannot be a coherent argument justifying Palestine’s ethnic cleansing that Jews need a state to prevent a “second Holocaust,” if, of the many places on the planet where Jews currently reside, the only one where they face such a dire prospect is Israel. Indeed, nowadays Israel has arguably become the principal fomenter of anti-Semitism and menace to the welfare of world Jewry.

Shavit denotes the Nazi holocaust “Zionism’s ultimate argument.” He recalls that more Jews perished at the Nazi killing field of Babi Yar than “in all of the wars of Israel.” After emerging from an Israeli Holocaust memorial’s “tunnel of…devastation,” Shavit “cannot help but feel proud of Israel. I was born an Israeli and I live as an Israeli and as an Israeli I shall die.” Stirring words, for sure, but what exactly do they mean? True, fewer Jews have perished in Israel’s wars than at Babi Yar, but fewer Jews still have perished in the diaspora. So, how can the Nazi holocaust be Israel’s “ultimate argument”? True, in the state created by Zionism, Shavit can live and die as an Israeli, but by his own admission the secular milieu in which he is ensconced lacks Jewish content. So, how can living and dying as an Israeli vindicate Zionism?

In the book’s final pages, Shavit drops any pretense that the state created by Zionism can be justified by reference to it:

It is a weird odyssey that Shavit has traversed from the book’s first pages to its last ones. He starts by frankly acknowledging the ethnic cleansing of Palestine’s indigenous population by the Zionist movement. He proceeds to justify this crime and Israel’s attendant creation in the name of Zionism’s supposedly higher justice: to avert the spiritual and physical destruction of Jewry. By the end, he discards these rationales and justifies Israel’s existence still in the name of Zionism but on the grounds that Israel has enabled Jews to live “dangerously,” “lustfully,” “to the extreme,” and with “vitality.” What any of this has to do with Zionism is anyone’s guess (wasn’t Zionism supposed to enable Jews to live not “dangerously” but safely?), while how it can possibly justify ethnic cleansing simply baffles and bewilders. Was it okay to expel Palestine’s indigenous population so that Jews in Tel Aviv could boogie?

The fact is, there is no “ultimate argument” for Zionism, let alone one that justifies ethnic cleansing. Zionist ideology originally possessed a superficial plausibility. A century later, it lies in tatters, nowhere more so than in the pages of Shavit’s book. It is improbable that Shavit’s Zionist apologia will persuade American Jews. His implicit contention that Palestine’s (alleged) backwardness mitigates the fate visited by Zionism on the native population will find little resonance among Jews with a liberal sensibility. The claim that Israel has provided an answer to the spiritual and physical dangers threatening Jews will also not convince. The pleasures one can indulge in Shavit’s beloved Tel Aviv do not spring from the “Jewish spirit” and can be indulged on a much grander scale in Manhattan. The notion that Israel provides a refuge against a “second Holocaust” would appear to be the reverse of the truth: nowhere are Jews more endangered than in the Jewish state, which is why so many Israelis have taken out a second passport. American Jews no doubt feel a special bond with Israel, not because of Zionism, however, but because of a primordial connection grounded in blood. They will identify with Israel in moments of existential truth, i.e., if and when Israel’s physical survival is at stake, but not much beyond. Israel offers nothing to American Jews that they don’t already have in abundance, while a lot of what it does have in abundance—racism, warmongering—leaves American Jews, if not disgusted, at any rate, embarrassed.

Israel exists: that is its ultimate argument. It is a state like any other state, and has the same rights and obligations as any other state. Yes, it was born in “original sin,” which no amount of Zionist apologetics can erase. But most (if not all) states have originated in sin. It would be more prudent if Israelis put behind them, finally, Zionist mumbo jumbo and made reparation for the colossal wrong inflicted on the people of Palestine.

The above is excerpted from Old Wine, Broken Bottle, from O/R Books.

Norman G. Finkelstein is a writer and lecturer. He is the author of many books, including Knowing Too Much: Why the American Jewish Romance with Israel Is Coming to an End, What Gandhi Says: About Nonviolence, Resistance and Courage, and the international bestseller, The Holocaust Industry: Reflections on the Exploitation of Jewish Suffering.