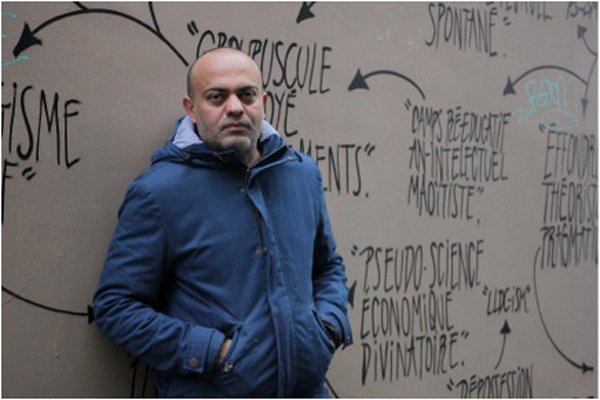

Since its publication by Penguin in February, The Corpse Exhibition: And Other Stories of Iraq has been celebrated as perhaps the most important work of literary fiction printed in the U.S. to depict post-invasion Iraq from an Iraqi point of view. Culled from two preexisting British collections of short fiction written by Hassan Blasim, an Iraqi filmmaker and writer who was granted asylum in Finland in 2004, the book deserves to be read by Americans not just for its perspective on the war but for its psychological depth, and for the deftness with which Blasim interposes his flinty prose with hallucinatory moments of black magic. His heroes are Kafka, Calvino, and Borges.

Blasim himself began inventing fiction as a child, growing up in a Shiite Muslim household in Kirkuk and Baghdad with nine siblings, an illiterate mother, and a father in the military, who died of a stroke when Blasim was sixteen. Blasim wrote poetry, plays, and crossword puzzles, and went on to study at Baghdad’s Academy of Cinematic Arts, winning awards for his short films and attracting the less welcome attention of Saddam’s secret police. In 1998 he fled to Kurdistan, where he made his first feature under a pseudonym in order to protect his family.

In 2000, he illegally crossed the border into Iran and from there began a three-and-a-half year clandestine journey across Turkey and Bulgaria, ending up in Finland’s third-largest city, Tampere. There, he made shorts and documentaries for Finnish TV, and had two short story collections translated into English and published by the British small publisher Comma Press. The first, The Madman of Freedom Square, went on to be published in Polish, Finnish, Italian and in the original Arabic—though it was heavily edited, and banned in Jordan. The most recent, The Iraqi Christ, is currently on the shortlist for the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize, and both have won the PEN Writers in Translation Prize.

Blasim isn’t sentimental about his occupation. He has based stories on the real-life horrors experienced by family and friends, and a degree of unease with the acclaim he’s won as a result can be read into his story “An Army Newspaper,” in which a journalist becomes a star by plagiarizing the fiction of a dead soldier. “I constantly have doubts about the art of writing and the role of the writer,” he said. “Writing about the violence in Iraq requires much caution because events take place one after another and attitudes change and the bloody turmoil is constant.” In The Corpse Exhibition, people clamor to tell their tales for cynical purposes—to gain asylum or win a competition—as well as therapeutic ones, and the truth is inevitably laced with fabrications.

Despite this ambivalence, storytelling seems to be as necessary for Blasim as it is for his characters. “I am physically exhausted after finishing a story,” he told me, “and I feel like taking an extended break from writing… but soon enough I get back to it. I get confused and extremely lonely when I’m not creating.”

Blasim emailed answers to my questions in Arabic, and they were translated by Jonathan Wright, the translator behind all the English-language collections of Blasim’s work.

—Jessica Holland for Guernica

Guernica: Can you describe your childhood in Iraq? How you have seen the country change?

Hassan Blasim: The Iran-Iraq war began the same year that I went to primary school, at the age of six. We were living in Kirkuk and the city was unstable because of the Kurdish resistance and the atmosphere of war. In art class at school we learned how to draw tanks and soldiers opening fire at [Iranian leader Ayatollah] Khomeini and his beard. They didn’t teach us the names of the flowers that grew around us in the city—wild flowers of all kinds and all colors. The math teacher used to whip the kids with his trouser belt. My father was constantly violent toward my mother for the most trivial reasons.

We used to watch executions. I mentioned that in one of my stories. There was a piece of open ground near the area where we lived and we used to play soccer there. That was where they used to hold public executions for soldiers who deserted the army and members of the Kurdish resistance. They would tie the victims to wooden posts and leave the posts there afterward to frighten other people. We children would take the posts later and use them for goalposts.

I’m talking about the essence of humanity. Hope is mixed into the blood of every human being, everywhere and in every time.

There’s no violence worse than the violence of Iraq. For the last fifty years Iraq has been living a nightmare of violence and terror. It’s been a horrible experience and people in Iraq will need a lot of time and work to get over the disastrous effects. But first we have to think about how to stop the violence, so that the bloodshed stops. In spite of everything, on the personal level I don’t easily lose hope.

Guernica: What keeps you hopeful?

Hassan Blasim: Losing hope means ceasing to love my son and my girlfriend and many friends and people around the world. We in Iraq have not descended from another planet. Just as people in many other countries have gotten over the tragedy of war, Iraq will get over its ordeal. I’m talking about the essence of humanity. Hope is mixed into the blood of every human being, everywhere and in every time. It’s true that we in Iraq are now paying a heavy price as a consequence of senseless violence, but nonetheless there are many positive things happening generally on the part of people in Arab countries who were living in darkness and absolute silence because of dictatorship. The people in Arab countries are now speaking out and asking many questions about human rights, minorities, religion, democracy, “the other,” and so on.

Guernica: When did you first start writing, and at what point did you start using colloquial Arabic in your work?

Hassan Blasim: I began writing and became attached to writing at an early age. I began by writing poetry and experimenting with dialogues: modest plays, in other words. I also used to describe at great length the way people in the area lived. I also wrote crossword puzzles, some of which were published in a local newspaper while I was a teenager. But I didn’t start publishing literary texts until I had left Iraq. At the Academy [of Cinematic Arts] I was busy with short films.

It’s ridiculous and painful to use the Arabic of an Iraqi poet who lived centuries ago to describe what we in Iraq are suffering today.

I’ve spoken about the problem of literary and colloquial Arabic on several occasions. I still write in literary Arabic but I try to rid it of the rhetoric, the symbolism, and the stuff that ordinary people don’t understand. I often use colloquial [language] in dialogue. In future writings I’m going to try to use more colloquial. All the children in the world, when they go to school, have the right to study in their mother tongue. But we go to school and run into literary Arabic as children. It sounds like a foreign language. The words for “house” or “table” or “lamp” are not the same as the words we use at home, and most of the other words are alien to children at school. Classical Arabic is one of the prisons of the Arab world. You learn something from the classics but your feelings and your imagination operate in the domain of the colloquial. We need to think seriously about reforming the Arabic that we use today. It’s ridiculous and painful to use the Arabic of an Iraqi poet who lived centuries ago to describe what we in Iraq are suffering today, for example. How can one talk in a classical language about a child who’s torn apart in an explosion in the market near his school? People in Iraq don’t talk about their joys, their problems, and the destruction of the country in literary diction.

Guernica: As a filmmaker during Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship, you were threatened by the secret police. What compelled you to keep working, and were you afraid?

Hassan Blasim: In fact I didn’t think about fear much at the time. I felt angry about everything that was happening around me: the violence of the dictatorship and the violence of society. While I was studying film at the Academy, the problems started. I wasn’t a political activist directly in the time of Saddam, because the dictator was so cruel and brutal that no one could criticize or complain. I felt futile and empty. The only solution in Iraq was to run away.

I studied at the Academy during the years of economic sanctions. Life was almost dead because the sanctions imposed on Iraq by the civilized world were so strict. We paid a heavy price in those years for the crimes of the dictator, who had been supported by the West and America for many years. The Academy of Arts was hardly functioning as well. I was active and set up a film group inside the Academy and started to make films. Although the films didn’t criticize the regime directly, the Baath Party in the faculty tried to frighten me. I was questioned several times. One of the Baathists once told me, “If you’re not careful, I’ll have you put away,” and those words meant death. I felt stifled and I very much wanted to run away and talk freely. Whenever we went out to film in the street we would end up in the police station and in the offices of some other security agency. They deliberately intimidated us. I moved to Kurdistan and changed my name and made my first feature film in Kurdistan with very basic resources.

“Secret migration” across borders is a form of human degradation and evidence of the depravity of the human conscience.

Guernica: How did your experiences as an undocumented immigrant affect you?

Hassan Blasim: The trail of “secret migration” was a shock to me. I knew a little about the difficulties, just bits of news in the media. “Secret migration” across borders is a form of human degradation and evidence of the depravity of the human conscience. I’ll tell you a short personal story. We were walking across the Turkish-Bulgarian border. We were a group of Iraqis and Nigerians. There was a fat young Nigerian woman with us and she found it hard to walk. Our smuggler, an Iraqi, suggested we take turns carrying her. Between us we carried the woman through a cold rainy night in the mud of the woods and fields. The Bulgarian army caught us at the barbed wire and beat us up. Then they took us to their military unit on the border. The soldiers raped the Nigerian woman in the room next door. We could hear her voice and we cried in silence. We had carried the woman through a cold, wild night so that the army of the modern world could rape her.

Guernica: How did you process this, emotionally?

Hassan Blasim: By writing, thinking, and imagination. Migration was not the only unpleasant experience I went though. I was born and lived in a country ruled by a brutal dictator whose wars never ended, and from an early age I was passionate about understanding the world through knowledge. Knowledge and imagination are the life buoy and the extra lung for breathing outside the walls of a tainted reality.

Guernica: You have said that you won’t participate in literary festivals in countries with poor human rights records, and that it’s important to express yourself without censorship. How does this affect your public role as a writer?

Hassan Blasim: The Arab world is full of corruption, in the time of the dictatorships and in the time of anarchy. This corruption is not only in politics and the economy, but also in the field of creative activity. There’s an elite that controls the festivals, the newspapers, and the reviews. They are just a corrupt clique with no interest in creativity.

I’ve been working on the margins and I was aware of this choice from the start. I buy most of what’s written and produced in the Arab world and I don’t much like it. For seven years I wrote and published my texts on the Internet and no Arab festival invited me and no Arab publishing house wanted to publish my books, and I wasn’t known in the Western world because of my political positions. I live in a small country in Europe—Finland—and I don’t speak English well and I had nothing to do with publishing houses in the West. I lived in complete isolation.

But when my stories were translated into other languages and received good reviews in the international press and won prizes, some Arab festivals and newspapers began to take an interest in what I had produced. This sudden Arab interest is a form of hypocrisy and nonsense. For example, the Abu Dhabi book fair now invites me to take part, but can the Emirates publish my work or print one of my books? Can any other Gulf state do that? Let them respect human rights and freedom of expression and then talk about a book fair. It’s just disgusting commercialism, like the new trade in slaves from Asia who work in the Gulf. My stories were translated and had many reviews before I had an interview with any international or Arab newspaper. If the stories hadn’t succeeded, you wouldn’t have asked me my position on Arab festivals and I wouldn’t have been interested in the festivals anyway, because I would be in seclusion, writing.

Guernica: How do you feel about the fact that you’ve won British awards but not any in the Arab world?

Hassan Blasim: Some Iraqi writers are more daring today and have excellent imaginations and their material is rich in human experience. But the Arab prizes, once again, are part of the context of life in the Arab world—anarchy, confusion, and corruption. I’m not much interested in prizes, whether from the Arab world or from the Western world. Writing is a very difficult process and I want to continue my work. For the International Prize for Arabic Fiction in 2014, one of the judges works in the Saudi Shura Council. The Saudi Shura Council is not a parliament that is elected and free and that defends the interests and rights of Saudi citizens. It’s an obscurantist council that is a tool of oppression in the hands of the king of Saudi Arabia and his family. How can someone who doesn’t speak out about all the human rights violations in his country judge a literary prize?

To contact Guernica or Jessica Holland, please write here.