T

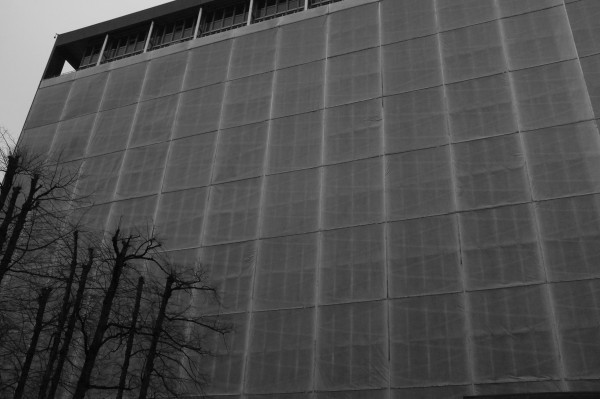

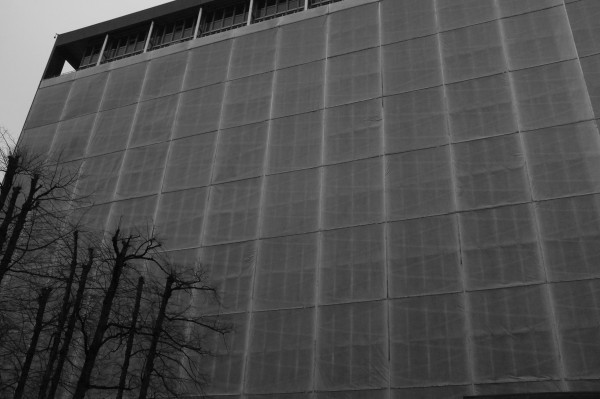

here is a tall green fence around the bomb site, but you can actually walk straight up to ground zero: the government high-rise known as Høyblokka, “the high block.” The building, which housed the offices of the Norwegian Prime Minister and also the Ministry of Justice and of the police, was the target of Anders Behring Breivik’s terrorist attack in Oslo, Norway on July 22, 2011. He set off his Oklahoma City-style bomb just outside the lobby, parking a van there with the bomb in the back. Eight people were killed, but the building still stands. It’s an empty shell, and what used to be a bus stop just in front of the building has been turned into a real-world version of those little museum texts placed next to the works of art on display: a short piece posted in Norwegian and English about what took place in 2011. “Ruins for the future,” says the note. “Relocating the past.”

According to state broadcaster NRK, neighbors of the planned memorial are now considering legal action to block the construction. The news story reports that they have engaged a lawyer, calling the planned memorial a “rape of nature” and a “re-traumatization of innocent witnesses to the 22 July tragedy.”

Immediately after the monument was revealed, the victims’ families started protesting. They hadn’t been consulted on the design, and were taken aback when they saw it—it’s not subtle.

The building is empty because nobody can decide what to do with it. Tear it down and rebuild a stronger structure, because it makes financial sense? Or would Norway’s resilience be better demonstrated by renovating the damaged building and putting it back into daily use? The bureaucracy tasked with this decision is unable to live up to its task. Attempting to write a news story about the case, I questioned the relevant authorities and was given a diagram of the decision-making process. It looked like a multi-stage rocket, with no dates or numbers on it to indicate when any decision would be taken. A January 2014 deadline to choose between five possible redesigns was not met: We needed to wait for a report authorizing the menu of options first. Then, on March 1, a report that would pass verdict on whether preservation was feasible from a safety standpoint was released—but though it was positive, no decision was taken. Now, into spring 2014, we are still at the very beginning of the planning rocket. Every deadline so far has turned out to be a mirage, and this is not likely to change any time soon.

In the meantime, the monument for the Utøya victims was chosen so swiftly that nobody had time to ask the victims’ families for approval. The memorial was ordered by the Ministry of Culture, the Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation was responsible for facilitating and preparing the grounds for a permanent national memorial after the attacks, and a committee known as the Kleveland-committee led the work of choosing the site for the memorial. An artist’s rendering shows a huge granite wall carving a tranche out of the landscape. A tunnel leads to a viewing platform from which an observer can see, but not reach, the other side, where the names of all 69 Utøya victims are to be carved into the stone, probably in very large letters. Immediately after the monument was revealed, two and a half years after the attacks, the victims’ families started protesting. They hadn’t been consulted on the design, and were taken aback when they saw it—it’s not subtle. Numerous families went on TV to publicly distance themselves from the memorial, and to ask that their children’s names were left off.

I covered the ten-week-long trial of Anders Behring Breivik for The Associated Press and later wrote about it for n+1 magazine. After ten weeks of testimony over the summer of 2012, as we neared spectacle’s exhausted end, two psychologists who specialized in grief testified to what the families of the victims were feeling, and would be feeling for years to come. During that time I sat in the front row of the courtroom, just a few yards from the terrorist. Nearly two years later, I cannot determine if what I felt, sitting there, was the man’s presence or his absence. Perhaps for this reason it was a relief to focus on the victims and their families, whose breathing, sniffling existence in the rows stretching behind me was palpable and unambiguous.

An entire year had passed between the terror attacks and the trial—actually no time at all, for the victims’ families. I agreed intensely with him. I remember the woozy horror of that first year after my brother’s death.

As we neared spectacle’s exhausted end, two psychologists who specialized in grief testified as to what the families of the victims were feeling, and would be feeling for years to come. Dagfinn Winje and Are Holen attested that the bereaved families would experience intense grief for a year or two. Others among them would feel it longer, or differently. And a small group would suffer from a more complicated grief that returned and faded and reappeared again over the years. The two mental health experts had studied many tragedies to come up with these facts, including the Måbødalen bus accident of 1988 which killed 16, mostly children, and the Laksevåg bombing of 1944, where an elementary school in Bergen was accidentally bombed by the allies during World War II.

It was odd to consider the victims first as individuals, as I had been doing for the duration of the trial, and then as data points, each of whom would, as time went on, distribute themselves among the categories. Who was fated to end in the “complicated” category? I felt sorry for them already. I felt afraid to be one of them. In 2001 I lost my little brother David in a skiing accident. When one of the psychologists pointed out that the time that had passed between the terror attacks and the trial—almost an entire year—was actually no time at all, for the victims’ families, I agreed intensely with him. I remember the woozy horror of that first year after my brother’s death. It was an entire year of no pleasure except for tiny and immediate sensory things like waking up and feeling warm in bed. Sometimes a nice cup of coffee could do it. Outside of that, everything was raining. Seeing people planning for their futures made me incredibly mad, and this lasted beyond the first year. Didn’t they know they had no safety, that actions like wearing seat-belts and getting bachelor’s degrees were nonsense? I used to want to wreck and shred material objects that had lasted longer than my brother, but was also overcome by a huge tiredness at this idea. There’s too much to break it all; the world was and is full of stupid, idiotic, useless things that are still here when he is not. But now that thirteen years have passed, I don’t think of that daily. Sometimes I catch myself feeling some kind of gratitude, rather than what used to feel like loss, and I don’t know when this change sneaked in. At which point would I have been competent to decide a lasting memorial to my brother? Feelings change. Which one do we want, or need, to memorialize?

Whether or not the Utøya victims’ architecturally designed granite wall memorial gets rushed into being, it will be located at Sørholmen, near the scene of the crime, a place far outside town where nobody goes unless they have business there. Høyblokka, the government high-rise, however, is in the middle of town and unless you put in a lot of effort, you cannot avoid catching sight of it when walking around Oslo. I’ve mentioned the tall green fences all around it, the area seemingly turned from bomb site to building site in one seamless maneuver. What’s going on at that building site, though, is totally unclear and if the bureaucrats planning the building’s future have their way, nobody will know for quite some time whether to tear it down or keep it as is. Nobody is rushing that building into its next stage. It will stand there for years to come, empty and ambiguous, yet physically imposing and relentlessly present in the cityscape. That is our true memorial