I

t’s not very often that you set off for the theater with wilfully lowered expectations. I recently went to the Royal Court in London for a performance of Abhishek Majumdar’s play, The Djinns of Eidgah, set in my hometown of Srinagar, with near-zero expectations but also quiet prayers for it be good. There is a reason for this. A lot of Indian writing on Kashmir—not all, I hasten to add—in the press or in the cultural sphere, usually disappoints. It frequently toes an official narrative that peddles the Islamist bogey, more often than not it sees Kashmir only through the chronic territorial tug of war between India and Pakistan, and if it ever attempts to look at one of the world’s largest military occupations with understanding, it does so with the condescension reserved amongst an increasingly pro-establishment middle class for those tireless natives forever crying of victimhood. Even some of the brightest and allegedly liberal voices only hesitantly, grudgingly, depart from what is played out in a populist media or taught in sanitised middle-school history textbooks.

Majumdar’s elegiac, surreal, and often chilling theatrical look at contemporary Kashmir—or indeed by extension at any conflict between the powerful state and a disenfranchised subjugated population—proved to be a bright new addition to the small but slowly growing tribe of intellectuals, artists and journalists who take it upon themselves to debunk the canard-ridden narratives prevalent in a lot of the mainstream cultural spaces. The play revolves around orphaned siblings Bilal and Ashrafi. The brother Bilal (ably played by Danny Ashok) is conflicted between his allegiance to his people and land, and his duty towards his traumatised mentally ill younger sister who, it is made evident early on, is under the care of psychiatrist Dr. Beg. He believes that by fulfilling his promise as a star footballer, he can take better care of Ashrafi—whose days and nights are filled with fear and memories of their murdered father who used to tell stories of Amir Hamza and battles between good and evil djinns. His friends aren’t too happy that Bilal has been absent from the daily street protests against Indian rule and that he may even consider playing in the enemy’s colours to pursue his dreams. Much of the action takes place near Eidgah, a real prayer ground that is also home to Kashmir’s largest martyrs’ graveyard. There are djinns here, a metaphor for unresolved lives, stories and possibly for the increasingly thinning line between life and death. They emerge at dusk and one torments the psychiatrist Dr. Beg who is treating Ashrafi as well as thousands of other patients struggling to cope with trauma.

Majumdar dramatizes the anguish of the living amidst the dead in some disturbing set pieces, one of which deals with the shocking image of Bilal’s killed football mates whose feet are missing.

Ashrafi (Aysha Kala), scared, possessed and inextricably tied to the past, is forever accompanied by a straw doll named Hafiz (literally, memoriser or one who has memorised the Quran), quite clearly a nod to the role of memory amongst a people wracked by war, oppression and prison-like living conditions. A deft touch, indeed, that even a mentally disabled victim has chosen not to forget. Majumdar is terrific in assembling many familiar stories of war/suffering—torture, murder, rape, loss—and rendering them afresh with haunting piquancy.

Majumdar’s writing is both direct—visceral even—and metaphorical, although the Djinns were overplayed and by the end of the performance assumed a less arresting function. It should have perhaps been enough that Dr. Beg’s dead militant son appears as a Djinn now and then to torment his father who is opposed to an armed struggle and is—it is later revealed—preparing to be part of negotiations with India. Majumdar dramatizes the anguish of the living amidst the dead in some disturbing set pieces, one of which deals with the shocking image of Bilal’s killed football mates whose feet are missing. And in a brilliant dramaturgical manoeuvre, the dramatist and the director have the set often moved around by the two actors who play Indian soldiers on duty near the martyrs’ graveyard. They define the physical space in which the play is set, and therefore the framework of the historical narrative we’re witnessing. The entire production, set, and lighting are extremely well stitched to the text, a reminder that dramatic technique can be effectively deployed to complement, even enhance, the text. Director Richard Twyman excels in creating spaces that shift mood, from the poignancy of the imaginary dribbles Bilal plays with his mates on an imagined football pitch to the claustrophobia of the torture cell Bilal ends up in, his only wish that the doctor keep his sister safe.

When the sufferers in Majumdar’s world seethe with anger and mourning, they’re aspiring to a fuller, more human life of dignity.

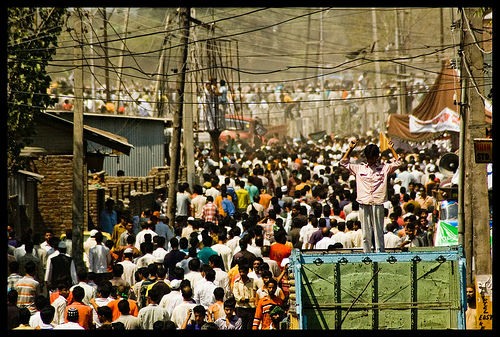

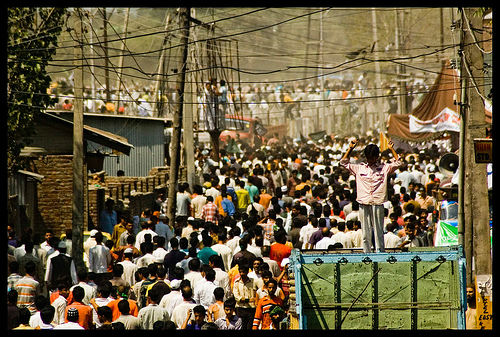

There are some misframed binaries that at times set the conflict in the narrative, and by extension the dispute in Kashmir: between “separatists” and the state; between active street protestors and those who for personal reasons may not be able to participate; between father and son on the opposite ends of the political spectrum. There is a mass of people in the middle who, too, intensely resent the occupation of their country, out of whom the protestors or militants rise. Djinns makes no bones about what the people of Kashmir it depicts want or aspire to: complete freedom from an occupying military state.

The sufferers in Majumdar’s world are therefore not shown as merely answering a revanchist tendency but when they seethe with anger and mourning, they’re aspiring to a fuller, more human life of dignity.

The dialogue between Dr. Beg, whose militant son is dead and who is preparing to talk to the government on Eid, and his assistant who is proud of having seen her little son show a fist to the soldiers, throws some light on the complexities of a conflict and the challenges of writing about it. The young assistant (Ayesha Dharker in a strong cameo) urges her mentor to free himself of his obsessive rationalism and delve deeper into a free heart; the senior medic, however, is critical of the battle for freedom that consumed his son and believes people may have harmed the very thing for which they are fighting. Towards the end of the play, the doctor himself is killed by a soldier with whom he wants to reason.

Even as the play briefly attempts to strike some kind of balance between multitudes of soldiers and those who throw stones, the trauma and the consequent unhinging of the soldiers, as a friend observed, is linked not to the rebellious people who hate them or to the militants who fight them, but to the actions of their own colleagues. The soldier driven to insanity and murder in the city—he shoots the psychiatrist as the latter tries to calm him down—is haunted by the eyes of the girl whose mother was raped by his commandant during a posting in the mountains from where no news can come.

Majumdar’s play is writing that ought to be celebrated for its artistic bravado and for its honesty and moral gumption. The play may appear fragmented to those not familiar enough with its backdrop, or, as that often misplaced criticism goes, assume too much knowledge on the part of the audience, not least owing to the surrealist staging. But that’s perhaps fitting, appropriate to its aesthetic intent, for it doesn’t seek to create a political whole or close a story.