How long must we dream of a thing before waking to find it in the room with us, having arrived there as might an odor—agreeable or not—whose source lay in another part of the house, engulfed in shadows that are themselves a warrant of mystery and the unseen? To say as much in my case, however, is to belie the nature of the apparition, which was odorless (except for a quality of dampness) and endued with a ponderous majesty, ridiculous in so meager and worn a place as my room was then. What is more, it produced a cold draft, as if a window had been left open on a winter’s night. I am prepared for your disbelief, even for your derision, although my personality, judged to be “fragile” by experts, would suffer by it. Perhaps fear of ridicule has kept me from naming the object that last night precipitated out of my dream like a salt—a disclosure not to be put off any longer if I am to keep your attention. If I have not already forfeited it, like a striptease artist slow to shed her gloves.

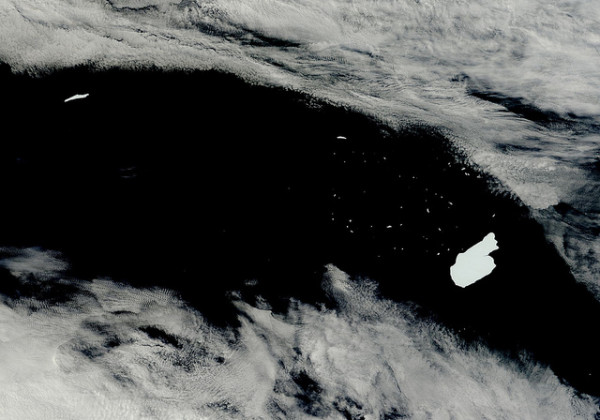

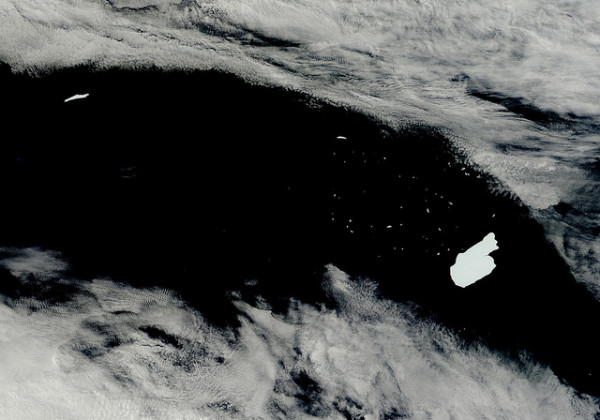

Dressed, I drew aside the rime-stiffened curtain and gazed out on a flotilla of icebergs gliding solemnly down the flooded street.

To get to the point: last night an iceberg slid out of my mind and into the room, sheathing first the windows and then the walls with frost. To be precise, an iceberg calved by the powerful torque of the imagination ascended from my unconscious depths, where it had been submerged for who knows how long, and, breaching a surface roiling with broken and commonplace dreams lacking its chill grandeur, slipped into my bedroom. That last line (gorgeous or gaudy, as you like) may suggest a mind hopelessly mired in fantasy, but you would be mistaken to dismiss me as delusional or mad.

Freezing, I sprang from bed and assembled, in darkness relieved only by a bluish gleam cast by the iceberg, sweaters, flannel pajama bottoms, my heaviest wool socks, and a down-filled coat suitable for an assault on Everest. For the iceberg that crowded my bedroom was no symbol of the world’s entropy or of a man’s estrangement from his kind, nor was it any longer a figment of the dreaming mind. (We don’t suffer cold in dreams, nor do we sneeze as I did twice while fumbling at my clothes.) Dressed, I drew aside the rime-stiffened curtain and gazed out on a flotilla of icebergs gliding solemnly down the flooded street. (To acknowledge, as you no doubt have, that I spawned one berg, a pack of them is easily granted.)

I stood at my window and saw, in its time, the sun rise and turn the icebergs rose, then violet, then green, then the blue of a summer’s day, whose heat, as it climbed toward the noon meridian, began to melt them—but not before one had torn from the apartment house opposite the balconies where my neighbors were leaning, as though to watch the procession of fantastic balloons during a Thanksgiving day parade. (In their buoyancy, so unlike these words of mine that seem to be minted of one of earth’s heavy elements.) I had scarcely time to wave goodbye before they plummeted into the rising water.

“Son of a bitch killed some of my best customers!” the grocer complained while we two stood and watched the departing ice dwindle in the sultry afternoon.

I had shed my heavy clothes and, made to squint uncomfortably by the glaring freshet, momentarily forgot that the destruction ranged about me had been caused by me—my own dreaming self, which, until now, had delivered nothing more intrusive than a book of stories much inferior to Kafka’s, Ionesco’s, or other of my literary influences.

“Is it the end of the world?” the grocer asked, tugging at my sleeve.

My mind elsewhere, the grocer jabbed me with an elbow.

“Is it the end?” he asked again.

I said nothing. What could I say? Had I told him that I was responsible for his loss (his mistake, to have extended credit in our unpredictable age), he might have fastened his grocer’s hands like beef steaks around my neck and squeezed. Frightened, I closed my eyes and with an effort of will hoped to erase him from the scene. After a moment, I opened them only to find him still there. Apparently, I had power to create, but not to uncreate. A great pity, for I would have sent the ice packing, back to the poles where it belonged.

To be rid of the grocer, I waded across the street, soaking my shoes and my pants to the knees—substantiation, should you require it, of the truth of what I have written thus far: the icebergs—for the moment, tamed—had been transformed from objects of fancy into artifacts of the subconscious mind, obedient to physical, rather than psychic, law.

The water in the street had lost its chill, had, in fact, grown warm during the sun’s progress toward an early September evening. The water had also deepened in response to the liquefaction of the polar remnants that had invaded the city. This, I knew, could mean only that my mind had finished what carbon emissions had been furthering: destruction of the ice caps. Why an admittedly hothouse imagination like mine, which had spent itself, more often than not, on sexual fantasies, had become an agent of earth’s dissolution, I could not guess. True, global warming had been much on my mind, now that an arctic ice sheet the size of the continental United States had vanished, the arrangement of its atoms altered by thermal absorption so that it must fall into the sea, fattening it. Soon, the ice caps would be no more than rock, their ancient element transformed into a deluge pouring, with dwarf bergs riding on its back, toward earth’s sultry middle.

How I was able to project onto the external world the reified image of my dread—this, too, I could not guess. Perhaps the mechanism, the concentrating lens by which my mind had unburdened itself, was guilt. Guilt for having kept my distance from the world, which all the world calls real. Guilt for having created a space all my own—like a room emptied suddenly of voices—into which an iceberg fell one night to finish us all.

I thought of Adele, whom I used to love. If the end had indeed come, I wanted to say goodbye to her. I telephoned, but she didn’t answer. Did she have caller ID, I wondered? Seeing my name, would she refuse to pick up the phone, even now? We had lived together for two years, drifting gradually apart (like a pair of stolid bergs!) until we spoke to each other scarcely at all. We did not quarrel; we simply gave each other space. The rooms through which we walked away from each other became uninhabitable. The space grew chill and vast, engulfing us finally in silence.

I sent her a text message: DEATH IS NOTHING NEXT TO LONELINESS. My cell phone tolled in answer: YOU MADE YOUR BED, NOW LIE IN IT.

“Did you hear anything last night?” I asked a vagrant who was poking at the water with a stick. Squatting next to the flooded street, he looked up at me—his shirt, a rag, his teeth, a ruin—and smiled as if to say, “You’re no better off than me, now we’re all about to be homeless.”

“Same as any other night: gun shots, screams, a barking dog, trucks on the overpass, an airplane so high not even its shadow touched the earth.”

I asked again, “Last night, did you hear anything unusual?”

He shook his head. “Same as any other night: gun shots, screams, a barking dog, trucks on the overpass, an airplane so high not even its shadow touched the earth.”

I pulled, skeptically, at my earlobe. Could a mere vagrant attain poetic heights (for me, cruelly unattainable), or had I misheard him, together with the ominous noises of the previous night?

“Nothing like a distant groan and a faraway rumbling?” I asked.

“I heard groans and rumbling, but they were mine,” he said fiercely.

Last night as I lay in bed, I had heard the unmistakable noise of an immense sundering, a furious giving way, a grievous, final separation. But had I been awake or asleep? If sleeping, had the sounds traveled from afar, or were they, like the vagrant’s, only my own?

“We’re the same now, you and me,” the man remarked with something like a sneer.

No, we had been traveling two divergent lines of thought: our minds would never meet. He went back to poking the water with a stick, and I went on my separate way.

I found a coffee shop untouched, for the moment, by the flood and ordered a café au lait. Across the street, a supermarket’s plate-glass window was visible beneath the water, and from where I sat, I could see two manta rays—secretive and aloof—gliding among shadowy aisles, their broad wings moving without effort in water that knew no urgency now that it had forced its way where water had never gone, in order to occupy it and impose its own idea of space.

“I’ve often dreamed of this,” said a young woman sitting at a nearby table.

“Pardon?” I asked, startled by a remark that made me wonder whether I was entirely to blame for the catastrophe—one I had not caused, but only hastened! Possibly the collapse of the ice shelves, the advent of the icebergs, and their death on the summery streets, down which they had, in their sublime folly, wandered, were the results of a collective dream. Perhaps, I said to myself as the woman (pretty, I was pleased to note) changed her table for mine, each iceberg had been begotten during the night by a different sleeper, in otherwise scantily furnished rooms like mine, after long hours troubled by dreams. But her next words disabused me.

“Venice. I’ve always wished I could live in a place with canals instead of streets.”

No, the fault was mine alone, though I had not conspired deliberately—that is to say, consciously—in the world’s end. (“Yes,” I would have answered the grocer now. “It is the end of the world.”) And as if to affirm my culpability, the woman set her cup clattering down on the saucer, flooding it, and pointed toward the street where, in silent reproach, drowned polar bears floated past.

I emptied my pockets of change for the waitress and left the pretty young woman, whose name I never learned, to her Venice. This story has nothing to do with romance. In fact, it’s not much of a story. I can’t even call it a cautionary tale, for the dire events related in it have already occurred and cannot, alas, be reversed. I left the coffee shop, intending to go home to take a shower, to change my clothes, to lie down and assess the situation, but I could no longer cross the streets. Sharks ruled them, lately arrived—I heard one man tell another—from the Indian Ocean, drawn to the warm brine of formerly frozen seas by the tang of dead polar bears, a taste unknown, till now, by the ecstatic predators (called white death by some), whose fins could be seen everywhere ripping seams in the turbid water. The primordial water, unlocked by dream or carbon or by infrared radiation had, while lapping the dirtied latitudes separating the poles from the Temperate Zone, lost its purity; but still the sharks came on—crazed by the abundant flesh, slow to spoil in the preserving salt.

The sharks would have their day and, like the icebergs, perish in streets so very distant from their range. Men would hunt them from the remaining balconies, with heavy tackle or rifles of a caliber sufficient to stop an elephant. When the last of the white death had been hacked to pieces, the woman, whose name I never knew, would realize her Venetian dream as gondolas plied the flooded streets, rowed by handsome men singing barcarolles in the shade of their straw hats. In the evening, I would stand on the shore of the illimitable ocean, watching the light go out of the sky and of the water, while the sun suffered its nightly death. And for a while, the world would be strange and beautiful; and we would adapt ourselves, as had we always, to the new life—carefree and charmed by its novelties.

—For Carolyn Kuebler and Stephen Donadio

Norman Lock is the author of story collections, novels, novellas, and stage and radio plays, including A History of the Imagination (FC2), Pieces for Small Orchestra & Other Fictions (Spuyten Duyvil), and, most recently, Love Among the Particles (Bellevue Literary Press). His new novel, The Boy in His Winter will be issued by Bellevue Literary Press in May and his book-length poem, “In the Time of Rat,” is due shortly from Ravenna Press. Lock has received The Paris Review Aga Kahn Prize for Fiction and the Dactyl Foundation for the Arts and Humanities fiction prize. More at normanlock.com.