In Austin, Texas one recent afternoon, a small group of women, and a few men, held a marathon reading of an unusual text: a transcript from the Texas State Senate. It was the 13-hour filibuster in which Wendy Davis tried to block a law that would restrict access to abortions around the state, an act of political theater that—though the bill was eventually signed into law and is now in the courts—has been immortalized as the origin story of a political star.

The reading was held at Spiderhouse, a cafe and bar near the University of Texas campus with antique bathtubs and statues surrounding multi-colored repurposed chairs, all of it illuminated by Christmas lights and old lamps. On a small wooden stage, people took turns reading several pages of the filibuster speech while audience members drank coffee and mimosas. Some followed along silently with the speaker, as if from a prayer book, while others buried themselves in smart phones, which is probably what a lot of the senators did during the actual filibuster.

It had the feeling of performance art, an element of Marina Abramovic-style repetition of the same act, where redundancy gives way to an altered sense of time as your mind goes in and out of attention. But unlike such strictly aesthetic experiments with long-duration experiences, this event also recalled screenings of Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah, the nine-and-a-half-hour documentary of interviews with Holocaust survivors, or the regularly held readings of Holocaust victim names. Boredom, in those cases, comes with guilt; how dare you lose attention in the face of such tragedy. Though the Wendy Davis reading was not quite so heavy, it made similar use of immersion and duration to foment politically charged emotions.

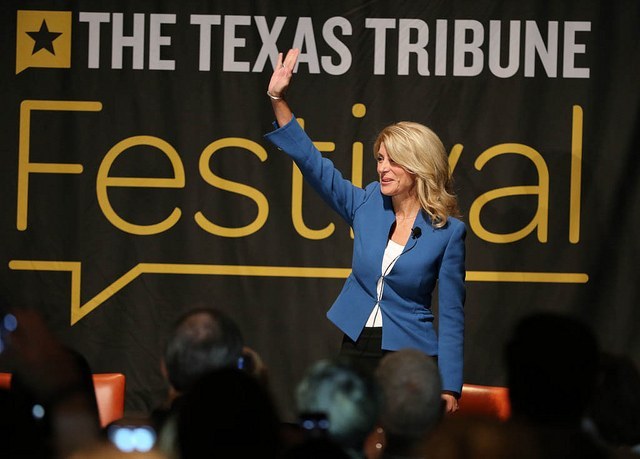

Davis announced her candidacy for governor on October 3rd. The election is still a full year away, and already Davis is more famous than Bill White, the former mayor of Houston who ran against Rick Perry in 2010, ever was. Davis was all but forced to run by the state’s Democratic Party, which has been invigorated by demographic predictions of a rising Latino population, but has been desperate for star power. The Castro brothers are famous too (they shared a Texas Monthly magazine cover with Davis recently) but they are younger and more liberal and not white in a state where all three characteristics are likely to make it difficult to win a gubernatorial race.

This reading of the filibuster speech, even if sparsely attended, showed just how excited people are here about Wendy Davis. “We are not affiliated with the Wendy Davis for Texas campaign,” read a disclaimer at the event’s website. “We’re just people. Who would like to see her win.”

The reading lasted only 6 hours instead of Davis’s 13, perhaps because people were reading more quickly and there were no stops for political refereeing and points of order. Some recounted these short speeches with a flat affect, while others took on a megaphone-ready zeal. A few cheekily imitated the Texas accents of the older male senators who challenged Davis, as if to mock their old boy manners. Both earnestness and sarcasm were paths to political righteousness.

The reading was a reminder that when Davis’s filibuster was going on, it was clearly an action: nobody thought about Davis’ words as a text or a document. It was a long and winding improvisation, dipping between readings of personal testimonials, broken up with answers to questions by other senators, and short debates over parliamentary procedures.

But this month, Counterpath Press, a small publisher based in Denver, will release the entirety of the filibuster as a 206-page book titled Let Her Speak!, the phrase used by protesters in order to keep the filibuster going until midnight. To celebrate the release, readings of the text are being held in Denver, Boulder, Durham, and New York City.

Jess Stoner, the activist and editor who organized the Austin reading, is the managing editor at the literary journal American Short Fiction, but has also worked on a state legislator’s staff and devoted herself to various causes. She told me that many involved with the nation-wide readings see the speech “as an experimental text,” a grand piece of political performance now memorialized as an object and an event. “It’s the idea of it more than the text itself.” By this logic, it doesn’t exactly matter what Davis said. It’s just important that she spoke for as long as she did in the interest of political theater.

On the page, the verbs don’t capture the intensity of the moment for those who attended. But the simple descriptors will give this political origin story a quality more in keeping with myth.

It is a dramatic, even engrossing document. For every repetitive diatribe, there is a heartbreaking anecdote, since Davis mainly read testimony from a prior public hearing on the bill. There were stories of rape, and stories of horrible medical complications. One woman told a story of getting pregnant by choice and finding out that her baby girl had been diagnosed with hydrops fatalis, a condition in which “an abnormal amount of the fluid builds up in the body.” The baby would die soon after birth.

“Being told that you don’t really have any control over how your baby is going to die is devastating and self defeating,” the woman said at a committee hearing, repeated as a theatrical monologue. Wendy Davis herself grew red around the eyes when she read this testimony: “I chose to have a baby and bring her into this world. I should be allowed to make the very personal, very private, and very painful decision as to how she leaves it, guided by the best interest of my child and my family.” Listening to this portion of the filibuster at the café, I looked around to see that the smart phones had been set aside and tears were streaming down most of the faces.

Peppered within the text are brief descriptions of what happened around the speech in the Senate chamber. At moments, it has the flavor of a screenplay. Here’s the dramatic conclusion, as Lt. Governor David Dewhurst tries to shut down the filibuster by deciding that Davis had broken a parliamentary rule by veering off topic.

Dewhurst: Members, after consultation with the Parliamentarian and after going over what, what people heard as far as discussion, Senator Campbell your point of order is well-taken and is sustained.

Gallery: [Extended yelling, shouting.] Bullshit! [Increased yelling, shouting.]

[Various attempts to speak by members.]

Dewhurst: Can you hear me? Senator Watson, can you hear me?

Gallery [chanting]: Let her speak! Let her speak! Let her speak! . . .

[End filibuster.]

On the page, the verbs don’t capture the intensity of the moment for those who attended. But as memories of the event fade from their sharp immediacy, these simple descriptors will give this political origin story a quality more in keeping with myth. In the Biblical story of Moses and the burning bush, we may imagine hearing a booming voice, but the text just says a voice “called to him.”

I met Wendy Davis briefly while covering the Texas Legislature earlier this year. She was charismatic, but not more so than many of the state Senators running around the capitol. Before the filibuster, I’d mention her name to friends and they’d stare blankly. The only back-story that readily came to mind was sort of bland: she won a close election in Fort Worth after several years on the city council.

I then spent the month of June on a music residency in New York City, performing with my band from Austin. The little bubble of Texas politics seemed far away, until the filibuster caught on in the national media (Guernica included). Friends I had never heard mention politics obsessively watched the live-stream of the filibuster. Some went to the capitol building to cheer her on.

To a Texan, this feels like a radical shift. Texas politics rarely takes to the national spotlight, and when it does, it’s because Rick Perry has said something about secession or homosexuality to make Northeast liberals laugh and shake their heads in disbelief. The Texas of liberal politicians like Ann Richards and Barbara Jordan existed only a generation ago. But there are plenty of voting age Texans who don’t remember it. Now, it feels like the state is more than a novelty. It’s once again a real center of the political conversations taking place in the rest of the country. For every strongly right of center politician we produce, there is now someone strong on the left. We can be the place where national issues are worked out, rather than a place for one side to fill the echo chamber before coming out swinging.

Despite her cult of celebrity, the conventional wisdom states that Davis would seem to have little chance of becoming the next governor because the state still votes so solidly Republican and voter turnout is low among the left. But then you think about the early days of Obama’s campaign. There is the same raw enthusiasm now. Old Democrats are sure to come out for her. New voters were galvanized by the filibuster. And as Stoner, the reading’s organizer, told me, we shouldn’t forget about all those 30 to 35 year olds, nurses and teachers among them, who may have never voted but now are passionately invested in issues like reproductive health and the education system.

A lot can happen in a year, though. Davis might alienate some of her earliest supporters by distancing herself from the pro-choice movement, since abortions are still a highly divisive issue in Texas. And Greg Abbott, the state’s current Attorney General and Davis’ all-but-assured Republican adversary, knows this. He’s a well-known figure only to the political and business class, but he has raised staggering amounts of campaign funds.

He can also match Davis in the inspirational back-story department: she was a young single mother who went on to Harvard Law; he has been paraplegic since he was struck by a tree at age 26 and would be the first wheelchair-bound Texas governor. She is beautiful and confident, but a little alienating, and we’re not exactly a state where being a beautiful, confident women always helps in the boy’s club of politics. Abbott is a member of that club, with the sort of voice that readers at the café mocked, precisely the sort of voice that makes him likeable to a lot of Texans. He recently appeared on the cover of Texas Monthly in his wheelchair, holding a shotgun. Open the magazine and you’ll find a friendly profile, in which writer Brian Sweany opens with Abbott shooting clay pigeons with his buddies. You could imagine profiles of our last two governors, Rick Perry and George W. Bush, opening the same way.

Over the course of the next year, the election will surely become a tired horse race. At Texas Monthly and The Texas Tribune, the state’s better known political commentators have already written dozens of articles about Abbott and Davis, the shadings of historical references, the Talmudic interpretations of vague campaign promises, and the speculation over demographics. We’re in for a long year.

But the filibuster—whether as a political memory, a text, or a regularly revived performance event—did one thing for the election. It took what could have been a total abstraction about “Texas Turning Blue” and grounded the fight in policy. The election will be theatrical, because all elections are, but the original piece of theater in this election was one with a purpose. Young Texans like the ones in the café that afternoon aren’t excited about Davis because of buzzwords like “Hope” and “Change.” They’re excited about what she would actually do as governor.