The Qasabji bar in Damascus, on an unremarkable road just outside the Old City, was where Khaled Khalifa and I had our best conversations. Khaled always entered first and greeted the customers sitting at tables near the door. He bent down, kissed the men, flirted with the women, and strutted to where Nabil, Qasabji’s owner, had cleaned a spot for us. He ordered either a glass of arak or the local Damascene beer, Barada, pulled a cigarette from his pack, lit it, and added to the purplish haze of smoke. Qasabji was a singular room shaped like a boxcar, crowded with wood tables, benches, and chairs that pushed against one another and three walls. I only saw it at night, crowded and smoke-filled, loud, dim. Khaled always faced out, better to see the men and women, but mostly the women, and when an attractive one entered he banged the table with his fist and hooted like a wolf.

I met Khaled Khalifa in 2007. He was a fellow at the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa, where I was working. His third novel, In Praise of Hatred, had come out in Arabic the year before, and within the year would be short-listed for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction, commonly known as the Arab Booker, and Khaled would be profiled by the New York Times.

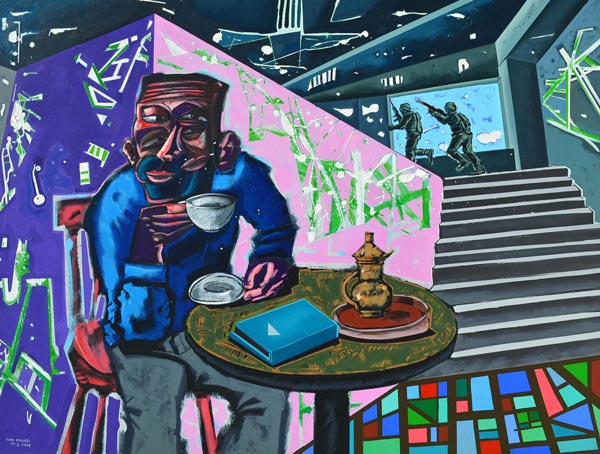

It was a romantic image, the focused writer, the devoted bartender, but everything about Khaled was romantic.

Qasabji was one of two Damascene locales where Khaled had often written In Praise of Hatred. He had worked until the early hours of the morning, Nabil serving him cup after cup of coffee. It was a romantic image, the focused writer, the devoted bartender, but everything about Khaled was romantic—his outsized personality (he once orchestrated an entire club to dance while standing atop a bar), his love of women (his womanizing is notorious), his capacity to drink (he buys Smirnoff vodka in two-gallon jugs, places them around his apartment, and fills them with olive oil when they’re empty). And when he talked about writing, he spoke with a refreshing earnestness:

“If you are going to be a writer, you need to be strong.”

“You cannot write a novel emotionally hot. You must be cold.”

“At one point, I decided that if I did not make it as a writer, I would kill myself.”

Khaled Khalifa was born on New Year’s Day, 1964, in a small village near northern Aleppo. His father was an olive farmer and owned an olive oil company; his mother raised children. Khaled was the middle child of a large family that would come to have nine boys and four girls, something he once told me allowed him the chance to get lost. Aleppo is Syria’s most populous city, a commercial hub that has historically been a meeting point of Eurasian cultures. Khaled’s family lived among this diversity. “There are two faces of the city,” he told me. “One face is like a ghetto. We were living there. I remember this neighborhood because all the poor people, like Armenians, Kurdish, Turkoman—these nationalities were living in the past. These were the poor people, the farmers, and they came from the villages.” There was another, newer, Aleppo, though, that was more cosmopolitan, more “Aleppine,” as Khaled called it. His family lived between these two cultures.

At the time of Khaled’s birth, Syria was nearing the end of a tumultuous political period. Syria was given independence from France in 1946; by the time of Hafez al-Assad’s coup in 1970, the Syrian government had been through four different constitutions, twenty cabinets, the formation and disintegration of a merger with Egypt, and four previous coups—three in 1949 alone. The turbulence was in part due to the end of WWII and the collapse of the Western colonial system that had dominated the Middle East between the two world wars. It was also a result of a blossoming Arab intellectualism in the wake of this fresh independence, the buds of which were often left-leaning and communist. Though Aleppo was historically a commercial town, not a political or intellectual center, it was not immune from these ideas, and its local cotton industry was the focal point of attempts to organize workers and put into practice what was being debated in Cairo, Beirut, Damascus, and Baghdad. Khaled’s older brothers brought these ideas into the Khalifa household.

By the time Khaled was in high school, a different political movement was developing in Syria. Though political Sunni Islam had existed in Syria since the 1930s, it grew following the November 1970 coup orchestrated by Air Force Commander Hafez al-Assad, father of the current president. Assad was a member of the minority community of Alawites, a heterodox Shia Muslim sect which came from the northwest mountains of Syria. He was also a member of the Ba’ath Party—the secular, left-leaning political party that had been founded by a Syrian and Iraqi in 1947. Throughout the 1970s, Assad’s Ba’ath Party faced mounting opposition from the Sunni Muslim Brotherhood in urban centers such as Hama, Homs, and Aleppo. This opposition culminated in assassinations of government ministers and military personnel, one of the boldest attacks occurring in June 1979 at the Artillery School in Aleppo, when many young officers were killed and dozens more wounded. Assad responded with brutal force, arresting, torturing, and murdering thousands of Syria’s citizens. In March 1980, an entire division of the Syrian army entered Aleppo, and for more than a year, it conducted house-to-house searches for sympathizers to the Brotherhood.

“I was translating a section on the university in Aleppo,” Leri Price, the novel’s English translator, wrote me over email, “and how there had been purges and murders of its professors, and when I turned on the news that night the BBC were [sic] running a story about purges and murders of the staff in the University of Aleppo. You couldn’t make it up.”

It is this bloody period in Aleppo’s history, when Khaled was a teenager, that In Praise of Hatred recounts. His narrator is an unnamed teenage female whose family participates in and is victimized by the violence. Like many great novels, it uses the personal to get at the national. But what is rare about In Praise of Hatred is that it does the dual work of documenting a period decades past while also illuminating the present. In March 2011, the Syrian people joined Arabs in other countries in revolting against their regimes, and the response by Bashar al-Assad, Hafez’s son, who took power when Hafez died in 2000, has been similar to his father’s. “I was translating a section on the university in Aleppo,” Leri Price, the novel’s English translator, wrote me over email, “and how there had been purges and murders of its professors, and when I turned on the news that night the BBC were [sic] running a story about purges and murders of the staff in the University of Aleppo. You couldn’t make it up.”

Khaled spent over thirteen years writing In Praise of Hatred. In one of our conversations at Qasabji, he said the novel finally fell into place when he discovered the character of the Yemeni, Abdullah, a man in his mid-forties who wants to marry one of the narrator’s aunts. That’s the character’s dramatic purpose. His intellectual purpose is to give background on the various Islamic parties and spin tales of martyrs and battles that captivate the narrator and send her to Aleppo’s religious frontlines.

No one wins in Khaled’s novel. Sectarian hatred leads to pain on all sides: families are torn apart; cities destroyed; memories seared; a country traumatized. Not surprisingly, like most art or writing critical of the regime, the novel is banned in Syria. Yet the novel is widely read there. Khaled likes to tell the story of its launch in Damascus, an event, he jokes, that drew the entire capital city. “On one side were all my friends, and writers, and other artists. And on the other, was all the Mukhabarat,” the secret police.

In 2009, two years after I first met Khaled, I spent the summer in Damascus learning Arabic. On my second night in the country, Khaled picked me up from my hotel. Short and stout, the nexus of his body lodged in his rotund gut, his curly salt-and-pepper hair bushy on both head and chest, he engulfed me in an embrace and said, “Matt, Matt, welcome to Damascus, my friend, welcome to my paradise.”

His red Peugeot had a large scrape and dent along the driver’s side door from a recent accident. Inside, empty and half-empty Gitanes Lights cigarette packs littered the floor, and there was so much white ash on the dash, the seats, and the consul, it looked like it had snowed inside the vehicle. We turned out of the parking lot and found our way to congested Al-Thawra Street.

We drove to a store and bought chicken, vegetables, and hummus and then drove to his apartment. Khaled lived up a mountain and across from a mosque. I spent several evenings at this apartment, usually for dinner, usually as a prelude to Qasabji or his favorite club, Mar Mar. There were two bedrooms (one for sleeping and fucking and the other for writing); a large living room with a television, usually tuned to Al Jazeera; a balcony with a view of the lights of Damascus; and a sizeable kitchen. Khaled’s money came from writing television scripts. He was quite good at it and was paid handsomely, and sometimes, when I was at his home, I heard him arguing with producers or directors over money.

His first love, though, was poetry. Khaled began writing in childhood, publishing poems as early as the fifth grade. At university in Aleppo, he discovered fiction, and by his second year, he was writing his first novel. He tore it up.

“You tore it up?” I asked during one of our conversations at Qasabji.

“Yes, because I felt it was not my voice. I took the voices of other Arab writers. It was very important for me because I tore it up after two years of work. I wrote for two years, very important years for me. All my time was for reading and for writing and for sex and for hasheesh. And for discovering books and the city and the country. I discovered everything.”

Khaled studied law in college, though he rarely attended class. He claims he was able to graduate by cramming for college exams fifty days before they were given. When he graduated, he did his customary two years of military service required of every Syrian male and then moved to Damascus. He and his friends established a literary magazine called ‘Alif (the first letter of the Arabic alphabet) in order to create a new, modern Arabic literature. He wrote a novel, the first one of his to be published. “I left poetry. Good-bye poetry forever,” he said.

The novel’s publication ushered in the most turbulent period of Khaled’s life. He moved in with his parents to avoid being homeless. They hounded him to get a job as a policeman or judge, especially his mother, who worried not only about his financial situation but about confrontations with the government if he pursued his dream of becoming a writer. He told me he was very sad at this point, because he knew novels take a long time to write, and that any other work would take him away from his fiction. He lived in Aleppo off and on for five years.

Eventually, because of the strain with his family, he moved back to Damascus. He took money from friends for one year and wrote. He began writing for television, and when he sold his first script, “it was a very very very very big moment for me.” He paid his friends back. His mother couldn’t believe that he had been paid that much money for writing. His twenties were over and his thirties about to begin. It was 1993. He had just penned the first chapter of In Praise of Hatred and published it in his magazine ‘Alif. “But I felt it was not good. I wrote ninety pages and tore it up and started again. When I wrote the next twenty pages, I said, ‘Yes, this is my novel.’”

Thirteen years later it was done: a novel born of an idea when he was depressed and broke and unemployed inside his parents house in Aleppo—of memories from his time as a teenager whose city was at war. The novel and its writer have made an important impression in Syria, especially among its young. I met several twentysomething Syrians working in the international community who were effusive in their praise; a young filmmaker, Bassel Shahade, once pulled me aside with a smile to say Khaled approved of his film idea; and during an evening when Khaled and I were out to dinner with a young musician and writer, a waiter asked if I knew whom I was eating with.

“That’s Khaled Khalifa,” I said.

“No,” he protested. “That’s a god.”

In the early morning hours of September 16, 2010, I arrived in Damascus for the second time. Syria was becoming the place for foreigners to study Arabic. The country was cheap and fun and its Arabic dialect was often thought the language’s most beautiful. There was a sense that after four decades of secrecy and closure, a curtain was being drawn open for Syria’s Great Reveal. An influx of foreigners rented apartments or Arab homes in the Old City, creating an army of backpackers on the cobblestone streets where once Romans and Crusaders had walked. In more formal, geopolitical ways, Syria was receiving a second look. Once lumped in with North Korea, Iraq, and Iran as part of Bush’s Axis of Evil, the Obama administration placed the country close to the center of its Middle East policy. The idea was to further isolate Iran by making inroads in Damascus; President Obama nominated an ambassador to Syria for the first time since 2005, the experienced Arabist Robert Ford. Even the mainstream media showed a renewed interest in Syria beyond terrorism and international conflict. National Geographic featured a story about a new Syria opening up to the world; Vogue published a controversial hagiography about Asma Assad, Assad’s wife; and the Times ran a series of profiles of Syrian artists and intellectuals.

It was this last topic that had brought me back to Damascus. My first summer there, largely because of Khaled, I had met dozens of artists, writers, and filmmakers who had left Syria because of censorship or oppression or opportunity but were returning to a burgeoning creative scene. It was a part of Syria not widely known in the West, and I wanted to write about it as a means to explore Syria’s history, politics, and culture. A Fulbright Fellowship gave me nine months to do so, and before I left for Syria, I had formulated a rough arc of my nine months in the country. Because of the pervasiveness of Syria’s Mukhabarat, I decided to delay contact with people or issues that could potentially threaten the regime. No mention of politics unless they arose in context. No meetings with public dissidents. No interviews with political or religious activists. I would spent the first eight months meeting artists, writers, filmmakers, and musicians, asking them about their lives and creative work, getting a feel for the dynamic in Syria’s capital city, and then, with a month left, ask tougher questions that could potentially lead to trouble. The rationale was simple. It behooved both my own personal safety and those of my subjects to avoid complicated, political issues.

So in September and October, as I settled into a spacious apartment with a gorgeous, panoramic view of Damascus, a city that, legend has it, Muhammad did not want to enter for fear you only enter paradise once, I spent time with artists whose work was benign: a group of young artists experimenting with animation and video art who wanted to start a comic book series; a musician and singer in the Damascus Higher Choir who invited me to the group dress rehearsal for Carmina Burana at the redolent Damascus Opera House; and Bassel Shahade, the young filmmaker making a short film about a poet whose heart literally broke from failed love.

And, of course, there were my conversations with Khaled at Qasabji.

Khaled’s control of English was better than my control of Arabic, so it was the former that we spoke. We understood each other well, but if there were times when I wished language wasn’t a barrier, it was when we spoke about the Mukhabarat, the secret police.

In 2009, a couple days after I arrived, when Khaled’s English and my Arabic were at their worst, we had dinner at an outdoor café. We were eating chicken schwarma and drinking a kind of yogurt, sitting on plastic chairs, and a wedding party drove by with horns honking.

“Ah, just get to the fucking,” Khaled shouted, and then he hit my leg in cahoots.

This was at the peak of Khaled’s popularity in Damascus, the same summer when the waiter asked if I knew I was sitting with a god. Totalitarian regimes allow godliness in singular form, and I asked Khaled whether he had ever had contact with the government. His answer was choppy, and I’m not confident in its veracity, though it rings true. He said that when he began winning awards for In Praise of Hatred, he was asked to meet with one of Bashar Assad’s close advisers. The adviser offered Khaled whatever he wanted—a new car, a new home, money—if he would speak positively of the regime. He declined the offer.

A year later at Qasabji, amid the cigarette smoke and conversation, Khaled lamented the lack of development in Syria’s literary culture. He said many writers live abroad and that one of the reasons was the censors. But, he said, visual art thrives here, in part because Bashar likes and doesn’t really understand it. He pointed to the wall, where an abstract painting hung over the table, and pretended to be the Syrian president. “Yes, I think this is just fine,” he mocked.

He told me that a writer’s life was no different than any Syrian’s life—they all faced dictatorship and censors. A fruit vendor was as restricted as an artist.

Maybe it’s because of the recognition he has received, the acclaim that started in the Middle East, spread to Europe, and is poised to proliferate in Britain and the United States, but Khaled never seemed bitter when he talked about the struggles of being an artist or writer in Assad’s Syria. At our first dinner together in 2010, he regaled me with stories of his summer, which he had spent in Europe with an “important man’s wife,” answering questions from European journalists. He said they all wanted to know what it was like to write under a dictatorship, about what the censors were like, and what that means for him as a writer. He waved his hand. After three years, he said, he was tired of answering such questions. He told me that a writer’s life was no different than any Syrian’s life—they all faced dictatorship and censors. A fruit vendor was as restricted as an artist. Instead, he was eager to talk about the new novel he was working on. He held up his two pudgy index fingers and placed them parallel on a horizontal plain. “It is about the Ba’ath Party and the Syrian people,” he said, a smile creasing his face. “And how they never meet.” He moved his fingers in a straight line, always parallel.

The last time I saw Khaled in Syria was, of course, at Qasabji. It was October 9, 2010, and he was preparing to leave for a one-month writing residency in Hong Kong. He hoped to work on the new novel, which he was tentatively calling The Parallel Life. We spoke about our plans for the winter when he returned—how he was going to bring me to the mountains, to a home he was building, so we could write our novels in peace. How we were going to invite our Egyptian friend Hamdy and our Mongolian friend Ayur, both writers we knew from Iowa.

A few weeks later, in early November, I was sitting inside the University of Damascus campus. The previous day, a group of Fulbright Fellows had gathered at the university to fill out forms for Iqama, or residency. The application took all day, and we had returned to receive our passports with our Iqamas stamped inside. Everyone’s passport was ready except for mine and a friend’s. We were told to walk to the passport immigration police station close by and answer more questions. It became clear early on, when the officers asked us how many states were in the United States and what was the last state admitted to the union, that this wasn’t a routine clarification of answers. It became more apparent when we were escorted out of the police station and asked to get into an unmarked white van.

We spent part of the afternoon in jail for reasons we did not know. We were interrogated on three separate occasions, and were offered coffee, tea, and chocolate in a lieutenant’s office while watching American action movies. We waited in this office until evening, when we were told to leave the country. There was no explanation given, only a stamp in our passport that said: “You are welcome to leave Syria in 48 hours.” Before we left the station, a line of generals shook our hands and said: “Ahlan, wasalan.” Welcome. The next night, we traveled to the airport for a scheduled flight to Amman. A hawk-nosed border guard typed in our passport numbers and became confused. He visited his superiors, spoke with our Syrian handler. We were interrogated for a fourth time. Finally allowed to leave, we were given our passports by the handler with a warning.

“I shouldn’t tell you this,” he whispered. “But on their computers you are labeled as national security risks.”

Our deportation instigated three weeks of diplomatic wrangling between the US and Syria and between different agencies in the US government. At one point, John Kerry spoke with Bashar al-Assad about us, and Bashar said there had been a mistake and that we could return. The culmination of all this was a choice between Syria and Jordan; the caveat was that if I chose Syria and was detained or deported again, I would lose my fellowship.

I wanted badly to return to Damascus, but by Thanksgiving, I had chosen Jordan. Three weeks later Muhammad al Bouazizi self-immolated in the Tunisian town of Sidi Bouzid, which sparked the Tunisian Revolution, which sparked the Arab Spring, which I experienced from Jordan’s sleepy capital of Amman.

When revolution spread to Egypt, Khaled, back in Damascus, posted to Facebook: “If we succsed [sic] in Egypt, will win every where. [sic]” Protests in Syria began tepidly, as if waiting for results in other countries. On January 26, a man self-immolated in the fashion of Muhammad al-Bouazizi. A week later, a Day of Rage planned for February 3 netted very few participants. Yet by March 15, following the detention, torture, and murder of teenagers who had scrawled anti-regime graffiti in the southern Syrian town of Daraa, a town abutting the Jordanian border, a more cohesive protest movement coalesced. Protests were now taking place in cities across the country, with Daraa at its center. I followed Khaled’s response on Facebook.

March 18: Who can stop this raging sea of waves?

March 23 There is no third road ahead of us. We either live with dignity or die with dignity.

March 27: How alone we are in this world. Even the soil and the skies are against us.

March 27: If emergency law disappears, I will really quit smoking.

Snipers on top of buildings wantonly killed protestors in Daraa, Homs, and Baniyas. Reports emerged of torture, rape, mutilation. A singer’s vocal chords were yanked out of his throat. A cartoonist’s hands broken and smashed. Refugees poured out of Syria to the neighboring countries of Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan.

Apr 30: Those who inside wish to wake up and not see the name Daraa on the map, I tell you look inside for a second and you will discover that the beast that lives inside you will eat you and Daraa will remain the queen of cities.

May 3: Can someone explain to me how an artist, all kinds of artists, and a writer, all kinds of writing, and at the same time, the siege of Daraa? I swear I still don’t understand it.

In late July 2011, I returned to the US. I spent a night with my family in Chicago and then drove to Iowa City, where Khaled was teaching a writing course to Arab teenagers. He had told me to find him at Java House, a coffee shop on Washington Street full of young writers and burgeoning scholars, and when I walked in, Khaled was ensconced at a wood table, getting news on the revolution out through Facebook. He hugged me and we left to go outside so he could smoke. We talked about my deportation, the revolution, the regime, and Syria’s future. The revolution had only been on for several months, and successes in Tunisia and Egypt had given hope across the region and in Syria that other regimes would soon collapse. Khaled was ebullient. We covered many topics. He said that he hadn’t been restricted at all in his movements, that he wasn’t directly working for the revolution though he was broadcasting it, that the regime would fall and those in charge would be tried as criminals, and that when the regime fell, there would be blood for about a couple of months before things subsided.

That evening, we went to George’s, Iowa City’s Qasabji: a dim, narrow bar of perpetual darkness. We met friends who still lived in town and drank and talked late into the night. “I think now, in Syria, we have a very new idea,” Khaled told me. “Now I’m writing my new novel. I have been writing for four years. But now, I will rewrite it, because I feel it is old writing. We have a new time, and new ideas, not just for writing but for the people too. Now we can understand our people. We are talking about this with young writers. What will be the future, I ask. You must be better. Because after the revolution you have new ideas about writing and about all art. We will have new ideas.”

I drove Khaled to DeKalb, Illinois, the next morning, where a Syrian musician friend of his lived. The two men hugged and joked and watched Al Jazeera. They went to his back deck for a cigarette, and the friend told Khaled he shouldn’t return to Syria, that it was too dangerous. Khaled protested and said he must be there at this time, that he couldn’t leave now, that he knew how to keep safe. When he stood up, his pants were soaked. He had unknowingly sat on a chair with a large puddle. He smiled at me through his stubble.

Syria was disintegrating. In mid-August 2011, as Khaled returned to his country, President Obama called for Assad to go. In mid-November, Jordan’s King Abdullah became the first Arab leader to ask for Assad’s removal. The killing didn’t stop. In an interview with Barbara Walters that aired December 7, Assad said a leader who kills his own people is crazy. Two weeks later, a two-day military campaign began in the Jabal al-Zawiyah area in Idlib, killing at least 200 people. The Arab League called for Assad to step down on January 22, 2012, amid shellings and bombings of cities like Homs and Hama. On February 4, China and Russia vetoed a UN Security Council resolution on the violence.

January 18: Sometimes silence is a tank

January 19: The last chapter is the most difficult chapter to finish in a revolution, as in a novel

February 6: Khaled sent a letter to friends around the world that began: My friends, writers and journalists from all over the world, in China and Russia, I would like to inform you that my people are being subjected to a genocide.

On the same day Khaled posted his letter to Facebook, the US Embassy in Damascus shuttered its doors. More than a month later, the UN and Arab League supported the Kofi Annan proposal to end the violence. On March 31, the Assad regime claimed victory over the opposition. On April 12, a UN-backed ceasefire began. On April 25, many children were among the sixty-nine killed during shelling of Hama. On May 3, an eighteen-year-old student at the University of Aleppo, Khaled’s university, was tossed out of a five-story window for protesting the Assad regime. On May 25, ninety-two people, thirty of whom were children, were massacred in the Sunni city of Houla.

On May 26, in a funeral for a friend who was shot in the head during a peaceful protest, Khaled Khalifa was beaten by security forces. His left arm was broken. On May 28, Bassel Shahade, the young filmmaker whose face had turned into a smile when Khaled approved of his project, who had left a Fulbright Fellowship at Syracuse to train activists how to shoot video, was killed by shrapnel in Homs.

May 29: Who doesn’t know our martyr Bassel Shahade, I tell you he’s a kid who knows only the rays of light. Bassel, you broke our hearts.

June 1: Bombings, bombings and bombings now

June 3: Unbelievable bombings and heavy gunfire

July 20, 2012, in a Facebook message to me: Hi Matt, until now I am safe, but under bombing and fear. Don’t worry.

Perhaps because of its premeditation, it is the death of the eighteen-year-old tossed from the fifth floor of Aleppo University that sticks with me. Its only solace is that somewhere in the city of merchants on the Old Silk Road, there is another Khaled Khalifa taking note.

“I cannot say more in these difficult moments,” Khaled wrote in his letter to writers and journalists across the world, “but I hope you will take action in solidarity with my people, through whatever means you deem appropriate. I know that writing stands helpless and naked in front of the Russian guns, tanks and missiles bombing cities and civilians, but I have no wish for your silence to be an accomplice of the killings as well.”—Khaled Khalifa, Damascus

In 2012, In Praise of Hatred was translated into English and published in London by Doubleday. The ending had changed. In the Arabic original, the unnamed narrator leaves Syria and joins her uncle in London. In the English translation, the novel ends with the narrator discharged from a lengthy prison sentence, presumably to remain in Aleppo. Khaled was furious with the change, but, he told me, he was in Damascus, so what could he do.

Ever since the war began in January 2011, I had little doubt that Khaled Khalifa would remain in Syria, in Damascus, his paradise, to help usher in the new ideas he spoke passionately about in Iowa City. More than two years on, however, I wonder whether this ending will change, too. Khaled’s health is failing; he is depressed; he has been barred from leaving the country. I get none of this from him, only those close to him. From him, I get positive emails, an optimism as much at Khaled’s core as his rotund gut and passion for writing. Khaled’s fourth novel was recently published in Cairo. I’ve also heard that Qasabji is still open, Nabil still serving arak and beer, albeit at a higher price.