2011, Karachi. I find myself looking at an illustration of an airplane colliding with the World Trade Center. Fire and smoke plume from the buildings. Below the illustration are the words, in Urdu: “Tay—Takrao.” Translated, they are along the lines of “C is for Collide.” The image is in a textbook for first-grade students who are learning the Urdu alphabet. “Jeem—Jihad” and “Hei—Hijab” follow (the accompanying illustration shows a woman in top-to-toe niqab rather than hijab).

The fate of Pakistan is dependent on the state’s ability to impart education that enlightens students rather than pulling them into the darkness of obscurantism.

“Madrassas,” I say, shaking my head. But the friend showing me the illustrations says such books can also be found in schools that aren’t within the madrassa system. She suggests that I look at some government-issued textbooks before coming to any conclusions about the wide gap between education in madrassas, which are largely unregulated, and education that follows the National Curricula.

So the next day I went out in search of government-issued textbooks. I came upon one for social sciences published by the Punjab government (each of Pakistan’s four provinces has its own textbook board). Flipping it open, I saw a chapter on the livestock of Pakistan. The section on “The Cattle” started: “It is a ‘Sunnah’ [custom; recommended practice] of our Holy Prophet to rear the cattle. By doing so, we fulfill our needs and at the same time obey the Sunnah-e-Nabi [custom-of-the-Prophet].” Further on in the book was a section on health, which began: “It is said that health is wealth.” But clichés weren’t the worst of the section’s problems. It ended with: “We need to make great efforts to solve the problems of our province so that all of us can live in peace and prosperity. We need to work selflessly and devotedly because to do what is just and virtuous in the eyes of Allah is a great Jihad.” That wasn’t the only mention of the J-word. Later, it merited its own chapter, which laid out the different kinds of Jihad, including Jihad bin Nafs: “A Jihad by sacrificing one’s own life and self. It means that every kind of physical effort may be put in for the service of Islam, so much so that one may sacrifice even one’s life for the propagation and cause of Islam.” Not so far from “Tay—Takrao” and “Jeem—Jihad” after all.

The fate of Pakistan is dependent on the state’s ability to impart education that enlightens students rather than pulling them into the darkness of obscurantism. Just educating children is daunting enough, but there is also the quality of that education. Pakistan has a shortage of qualified teachers, a reluctance in many parts of the country to send girls to school once they’re considered old enough to help their mothers with domestic chores, and a large number of “ghost schools” that exist on paper, are included in official counts, often receive international funding, but don’t, in reality, function as schools. Pakistan’s DAWN newspaper carried a photograph on April 30, 2009 of a “school” that was being used as a barn for animals. According to Pir Mazhar ul Haq, the Education Minister for the province of Sindh, there were 7,700 ghost schools in Sindh alone. But as the textbooks prove, education is not a word bathed in golden light; what and how children learn is at least as important as the fact of learning itself.

Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy, an Emmy award-winning filmmaker and trustee of the Citizens Archive of Pakistan (CAP), a nonprofit organization for cultural and historic preservation, spent time in different madrassas over the course of several years. There, she saw firsthand the language used by teachers to indoctrinate students. Not quite 1 percent of Pakistan’s 1.7 million school-going children attend madrassa (as opposed to the 66 percent who are educated within the formal education structure), but the number is still sizable and the indoctrination process isn’t confined to the madrassa system alone.

Using what they learned during a three-day workshop at the Museum of London and a baseline survey of government schools in Karachi, which confirmed the degree of hatred taught in schools as well as the lack of critical thinking, the individuals at CAP put together a “parallel curriculum.” They then set about using their contacts in the NGO world to find several schools across Karachi that would allow them to send in a team to teach their curriculum alongside the government curriculum for a few hours a week. When I first heard of this, I imagined “the team” as a vast and complex organism, but it turned out to be two twentysomethings, Adnan and Sarah, along with two technical assistants.

One winter morning in February 2010, I accompanied Adnan and Sarah to a school that had agreed to work with CAP. As we drove through Karachi, progressing from neighborhoods where bougainvillea climbed high boundary walls to those where political graffiti was painted on cement buildings, I tried to understand what a handful of people could accomplish when set against an entire education system—and also why exactly they might do it.

In Sarah’s case, joining CAP’s School Outreach Project was a natural progression from her student days in America where she studied history and wrote her thesis on a comparison between the textbooks of India and Pakistan. (“They’re as bad as each other in terms of teaching skewed history,” she says. “The only difference is India doesn’t feel the need to be as defensive about itself.”) Adnan, on the other hand, studied social sciences at university and then went on to work at an oil and gas company. “But I saw what was going on in Pakistan; I live here, this is my country. I had to do something, so I joined CAP,” he says. “I live here; this is my country” could well be CAP’s motto, I thought as I listened to him.

“With the boys you have to get to them by the time they’re eleven or twelve. Any later is too late,” Sarah said, recalling how a group of fourteen-year-olds told her, “What do we need education for? We’re in politics.”

On that day, they would be presenting a one-hour education module on Pakistan’s geography. This was the second and final visit to the school; the first had concentrated on history. They acknowledged that there was only so much one could do in terms of education in two hours. But they took the long view that the more projects and schools they were involved with the more exposure CAP’s school project would receive, thereby increasing the likelihood that other groups and individuals with resources would partner with them, expanding the project.

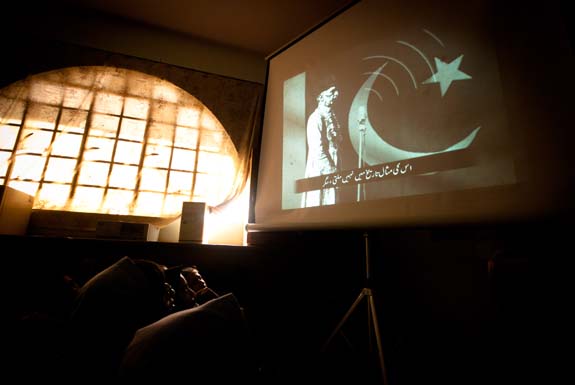

The workshops were still getting off the ground, but CAP had already been involved for several months in a longer-term project with five schools in Karachi. There, Sarah and Adnan were teaching weekly classes in Urdu. These consisted of twenty-four lesson plans that focused on Pakistan between the years 1940 and 1955, and included topics such as the creation of Pakistan, the role played by women in the founding and early years of the state, and the setting up of the influential Radio Pakistan. The lessons weren’t without reference to the present; conversations around the mass migration that accompanied Partition and the then government’s response to the influx of refugees were set against those about the large number of internally displaced persons in Pakistan following army action in Taliban-controlled areas in 2009.

When Obaid-Chinoy explained the structure and aims of the Outreach Project to me in the bright and breezy CAP office, it sounded straightforward. Talking to Adnan and Sarah made it clear that it was anything but. They said that the schools didn’t take what CAP was doing seriously, that they treated the lessons as extracurricular activities to amuse the children. That CAP used videos and graphics as teaching tools no doubt aided in this impression. Usually, the class teachers didn’t bother to stay and listen to what their students were being taught, though this was, in its own way, a blessing. One teacher who did take an interest was annoyed to discover that the students were being taught about Nehru and Gandhi, not as figures of hate but as politicians involved with the anti-colonial struggle whose differences with the Muslim League played a significant role in Partition. There was no point, the teacher had said, in teaching such things. Fearing being forbidden from any further teaching at the school, CAP removed the lesson from the curriculum for that particular school.

Adnan and Sarah soon learned that almost anything could cause offense; early on they stopped giving out handouts for the children to take home. “You never know what the parents will object to and create a fuss about,” Adnan explained.

One day near the end of the term, Sarah asked the girls if they were all going to come back the following year. One girl remained silent. When Sarah questioned her, she said, “What if there’s a bomb blast? I can’t come back if I’m dead.”

But problems didn’t just come from adults. Increasingly, the neighborhoods in Karachi are divided along ethnic lines with each group identifying with a political party. The relationships between some of these political parties are marked by violence and “target killing,” intimidation, and extortion to the perceived benefit of the party. By the time many boys are adolescents, they’ve already been pulled into some of the more thuggish aspects. “With the boys you have to get to them by the time they’re eleven or twelve. Any later is too late,” Sarah said, recalling how a group of fourteen-year-olds told her, “What do we need education for? We’re in politics.” Even further, those boys were unwilling to listen to a female. Once, when Sarah was trying to get them to be silent, one of the students said, “Get the bearded guy with a stick to come in if you want us to be quiet.” Not long after, she stopped teaching in the boys’ section of the school.

“What about the girls?” I asked.

The girls, she said, were an entirely different matter. “I can set any essay assignment, and without fail they’ll manage to work into it that their greatest wish is to just be allowed to stay in school and complete their education,” Sarah told me. But all too often their parents pull them out of school by the time they’re twelve. Sometimes the parents want them to get married, other times they can’t afford the fees and feel it’s more important to pay for the education of their sons.

The girls are as affectionate as the boys are macho, I heard from both Sarah and Adnan. It was hard not to think that at home their brothers received all the attention. Damaging for both the boys and the girls, as well as for their relationships with each other. For Sarah, it was particularly disheartening to realize how low the girls’ expectations for their lives were, how little they felt they could ask from the world. When she found a group of people to sponsor renovations to the school, which was “like a construction site, no, a disaster zone!,” she asked the girls what they wanted done in terms of renovations.

“Bathrooms!” they all agreed.

“Anything else?” Sarah asked.

“Paint?” one of the girls said.

“Don’t go overboard,” another student admonished her.

“No, that’s fine,” said Sarah.

“What else?”

“A swing!”

All the girls in the classroom looked at the student who said this as if she were crazy. In addition to all the complications of gender, there were other things that weighed on the students. One day near the end of the term, Sarah asked the girls if they were all going to come back the following year. One girl remained silent. When Sarah questioned her, she said, “What if there’s a bomb blast? I can’t come back if I’m dead.” And all the other students nodded their heads, “Oh yes, we hadn’t thought of that.”

I asked them if they liked school; this was treated as a silly question. Of course they did.

“But the school we’re going to today is one of the better government schools,” Adnan pointed out as we neared our destination. “They have blackboards and desks, and the teachers stay for our lessons. And the students already know some of the things we’re teaching them. There is a big gap between different schools. In the worst one we went to the students didn’t even know the capital of Pakistan or understand the concept of a continent.”

We arrived at New Star Grammar School during break time. A large sign describing the school as “Thoroughly English Medium” greeted us. The walls had neatly stenciled political graffiti on them, as did all the neighboring buildings, as well as a verse from the Quran and its Urdu translation. It was one of my favorites: “Read, and your Lord is most Generous / who taught with a Pen, taught man what he knew not.”

The boys were playing downstairs when we walked in, but a group of girls came upstairs to see what we were doing. I went up to them to say hello, and they all solemnly shook my hand. When I started speaking in Urdu, they replied in English. Thoroughly English Medium. Within a few minutes, though, our conversation had moved back to Urdu, as they proudly showed me around their classrooms. I asked what their favorite class was. Some said “Computers,” one said “Maths.” I asked them if they liked school; this was treated as a silly question. Of course they did.

By now the room had been set up for CAP’s lesson. Desks and computers were pushed against the wall—this was the only school with functioning computers that the CAP team had seen so far—and rugs were laid down for the students, both male and female, to sit on. Along the walls were posters of the human digestive system, and on the blackboard, elements of the periodic table. It was slightly embarrassing to be confronted with facts I knew at fourteen and now have little grasp of, but it made me think of something Obaid-Chinoy had earlier said: “The most important thing we have to teach is critical thinking. Let them disagree with our interpretation of events; that’s fine. But they must ask questions and think of possible solutions.”

Adnan and Sarah read out various facts about the provinces of Pakistan. The students had a slightly glazed look about them. Geography was my least favorite subject at school. I found myself becoming enormously interested in the faded, flower-patterned curtain that was keeping out the glare of the sun. Then Adnan asked the technician to start the video. Two animated partridges—one elderly and male, one young and female—flew onto the screen. Immediately, the students were rapt. The partridge is the national bird of Pakistan. I learned this when Adnan introduced the video. The elderly partridge was the grandfather, Nanoo, who was instructing his granddaughter, Zaino, about the country she lives in via his own memories, all illustrated in beautiful graphics. When he asked her how many provinces there are in Pakistan, all the students shouted at the screen: “Four!” Nanoo taught Zaino everything that Adnan and Sarah had previously read out loud, but this time, both the students and I were listening closely. When the video ended, Adnan and Sarah handed out a quiz to see how much of the information the students had taken in. Writing down what they had learned helped to further inscribe it in their memory.

It was an instructive morning, and the students clearly both enjoyed and learned from it, but in the end I was left wondering where CAP would go from there. Teaching in five schools and running two-hour workshops in a few more was not worthless, but it was less than a drop in a very torrid ocean. For all the claims that the exposure of working in these schools could lead to bigger things, I was skeptical. What Pakistan’s education system needed was a structural change. There seemed no way of getting around the fact that change would have to come from the government.

The much-vaunted Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution, passed unanimously in the National Assembly on April 8, 2010, included provisions to devolve certain powers, including education, to the four provinces. This hadn’t meant much. Two of the provinces had revised their schools’ curriculums and the results included the social science textbook that laid out the religious benefits of owning a cow and the glory of Jihad bin Nafs. That Sindh (the province in which Karachi is capital) hadn’t yet gotten around to the revision seemed entirely moot.

“So you’re optimistic?” I asked, unused to uttering that statement to anyone involved with Pakistan’s government and bureaucracy.

But when I went to see Obaid-Chinoy for a follow-up visit, she had news for me. The Sindh government’s Secretary of Education had agreed, after a fair degree of persistence, to meet Obaid-Chinoy and listen to her talk about CAP’s School Outreach Project. At the end of the meeting, the Secretary of Education—by all accounts a dynamic and no-nonsense woman herself—asked Obaid-Chinoy if she wanted to sit in on a meeting of the Curriculum Board.

There are those of us who watch a one-hour video presentation, and ask, but what can this really achieve? Isn’t it just a pebble dropping into an ocean, causing a minor ripple, and sinking to the ocean floor? And there are others who pebble by pebble build a reputation and an understanding of structural failings, which gets them through a door which puts them in a room with the people who will decide what the next generation of Sindh’s students will be taught.

Everyone involved, she said, was committed to genuine reform, and there was total agreement that obscurantism needed to be expunged from the classroom

Three months later, I spoke to Obaid-Chinoy again. She hadn’t just sat in on one meeting, but had become part of the committee for Curriculum Reform. Everyone involved, she said, was committed to genuine reform, and there was total agreement that obscurantism needed to be expunged from the classroom. To that end the Sindh government had already invited private publishers to submit books that could be used as texts, in effect, entirely dispensing with the existing textbooks and making it possible to bring some of Pakistan’s finest academics and writers into the curriculum. Plans were also underway for teacher-training projects, without which there could be no meaningful reform.

“So you’re optimistic?” I asked, unused to uttering that statement to anyone involved with Pakistan’s government and bureaucracy.

“I am,” she said. “You know, in Pakistan it just takes one moment, one person, to derail a process. But there are so many people who want to get this right. It’s absolutely crucial to the country’s future.”

Even as she said those words I saw them as the hopeful final words of this article. But in May, Naheed Durrani, who had been the guiding force behind the proposed changes, was transferred from her position as Secretary of Education. When I spoke to Obaid-Chinoy again near the end of the year, I asked for her thoughts on the reason behind the transfer. “She ruffled too may feathers with her plans to change the system.” And what did that mean for the curriculum reform? “Everything’s stalled,” she said bluntly.

“So is that it?” I asked. “Derailment complete?”

When her response came, it was the only possible one: “We can’t afford to let that happen.”