What a pirate festival, and dancing alone to Calypso, can teach us about the here and now.

People who like to trick themselves out in pirate attire and drink a lot of rum and beer take over California’s Catalina Island during an annual festival called “Buccaneer Days.” I learned this when a man I was seeing a few years ago took me on a date to Catalina; he thought it would be romantic in an adventuresome sort of way for us to snorkel the cold, slightly forbidding waters off the island’s coast. It was a not particularly sunny October day and the early morning ferry we boarded at San Pedro was not too crowded. We didn’t expect to see many people on Catalina. There was no doubting, though, as the ferry docked at the village of Two Harbors, that we had been mistaken: there were going to be a lot of people on Catalina. Many of them would be wearing a patch over one eye.

People who like to trick themselves out in pirate attire and drink a lot of rum and beer take over California’s Catalina Island during an annual festival called “Buccaneer Days.” I learned this when a man I was seeing a few years ago took me on a date to Catalina; he thought it would be romantic in an adventuresome sort of way for us to snorkel the cold, slightly forbidding waters off the island’s coast. It was a not particularly sunny October day and the early morning ferry we boarded at San Pedro was not too crowded. We didn’t expect to see many people on Catalina. There was no doubting, though, as the ferry docked at the village of Two Harbors, that we had been mistaken: there were going to be a lot of people on Catalina. Many of them would be wearing a patch over one eye.

After disembarking, we escaped the crowd and napped on a cliff on the other side of the island, ate lunch, rented wetsuits and an outboard, rode the boat to an outcrop, snorkeled around the rock for no longer than an hour, and before catching a ferry back to San Pedro, managed to grab seats at a bar where the pirates were gathering. The bay at Two Harbors was by this time packed with boats, and the bar and its patios were crammed with people whose pirate renderings showed little variation: eye patches, striped shirts, torn shirts, and—there were misfires—tricornes that appeared more colonial than flamboyant in design were everywhere to be seen. Plenty of women were scantily clad; there were many an overflowing bosom on Catalina that day. But then so many themed events invite that sort of thing.

As we watched the crowd drink, shout, and jostle each other about, a dancing man and woman caught our attention: the man wore a patch, a three-cornered hat, and so on; my memory of the woman’s attire is obscured by the thick rope that coiled around her waist and stiffly bound her arms to her back. (That the woman was black and the man was to all appearances white was not lost on me. Intentionally or not, they evoked something more than plain old pirating.) She danced despite her restrictions, swaying from side to side, seemingly content—serene, even—in the role of captured booty. Just as we were leaving, her dance partner tied her to the trunk of a tree.

The shipping cranes and barges our return ferry passed as it navigated San Pedro’s dark channels looked exquisite in the night. Giant headlamps shed sharp light on tall, brightly painted industrial structures and massive, hovering containers. After a few hours with so many pirates immersed in some vague and distant seafaring era, the scene offered reassurance. No square-rigged frigates in the San Pedro channels—just magnificent shipping machinery, the stuff that moves economies. Yes, I remember thinking, this is where we are.

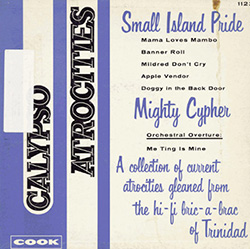

I thought of Buccaneer Days and the happily bound woman as I danced around my living room this past New Year’s Eve. I’d bagged on a plan to travel out of town and, a little exhausted from a busy month, couldn’t imagine being enjoyable company to the friends who invited me to join them here in New York. I decided to spend the night at home with a good meal, a good bottle of wine, and music that I like. About two hours before midnight, I downloaded two albums—Calypso Awakenings and Calypso Atrocities—and put together a playlist.

My memory of the woman’s attire is obscured by the thick rope that coiled around her waist and stiffly bound her arms to her back.

Both Awakenings and Atrocities collect performances by mostly obscure calypsonians recorded in the late nineteen fifties and early nineteen sixties by the American audio engineer Emory Cook. Cook traveled throughout the Caribbean—particularly Trinidad—and North America in search of ambient and evocative sounds: thunderstorms, carousels, trains heading toward Manhattan on the tracks of the Central Hudson Line, coffee percolating, and high-spirited calypsonians playing to crowds in what I imagine to have been sweltering Port of Spain halls, to name a few of his Cook Records tracks. A 1956 New Yorker profile of Cook explains that he had a special interest in what Daniel Lang termed “nostalgic sounds.” It was a far-reaching nostalgia that Cook had in mind; he believed that sound has the ability to summon not only individual memories—of being placed on a carousel horse by a parent or of a weekend trip to the city from up the Hudson, for example—but also, as Lang puts it, “the very origins life.”

At the time the profile was written, Cook had plans to travel to Nova Scotia to visit a cave in which the acoustics were said to be unique: he’d heard that water dripped from the cave’s ceiling to its floor in a “deafening series of plops.” He offered Lang a curious explanation for wanting to record the sound of the dripping water: “It could tap the racial unconscious. This isn’t just ordinary nostalgia we’ll be dealing with. This is straight atavism. From the cave to the present and back again. It may be the psychological scoop of the century!” Cook suspected, in other words, that the sound of dripping water is so deeply engrained in the human unconscious that we might, in hearing a good recording of those drips, be brought back to our earliest memories as a species.

Cook was so entranced by Trinidad’s music—the Cook Records catalog is dominated by recordings of the island’s calypsos, steel drums, and kalindas—it’s easy to imagine that he heard in it, too, something essential, something that might transport listeners if not to the cave then at least to some distant point in their shared history. And, of course, back to the present again.

I’d wondered just earlier that day—as I do when I’m bored with my music—what songs, what albums I would fall in love with next. Future obsessions are such mysteries. What will the next political intrigue be? Next natural disaster? Next love? Next good news? Next bad? Hard to say. I certainly couldn’t have guessed a few weeks prior that I would listen to calypsos on New Year’s Eve. Despite a genealogy that might suggest otherwise (my father is Trinidadian, as are my mother’s parents), I don’t very much like calypso. For all its political overtures, the music’s melodies are too often too cute for my ears. I don’t know whether it’s the influence of the officers stationed at American military bases in Trinidad during and after World War II or what, but something had happened to the music by the time the Americans relinquished control of the major naval base at Chaguaramas in 1963—I think of it as a dilution of earthiness, of something essentially Trinidadian—and I’m not sure it ever recovered. (Jamaica, which hosted, as far as I can tell, only one remote American air field and two small naval bases during the war and not for very long after that, doesn’t seem to have had so much of this problem with its chief musical export.) The Mighty Sparrow, maybe the best known of the calypsonians to emerge from postwar Trinidad, is more famous than his early-career rival Lord Melody, whose rhythms were so much more playful and whose lyrics were so much more charmingly self-deprecating than Sparrow’s, speaks, I think, to calypso’s relative failure as a genre.

But I’d seen my paternal grandmother over the holidays. Hearing her talk in her beautifully thick, sing-songy accent and make jokes—jokes that have become more and more vulgar as dementia has set in and that sound somehow distinctly Trinidadian to my ears (to the nurses who encourage her to use the bathroom after she hasn’t gone for a while, she is said to have once shouted in irritation, “What?! You want me shit for sell?!”; to an elderly man staring innocently into space as she passed him in a nursing home hallway, “You think you’re important? You’re not important! You’re IM-PO-TENT! You will never rise again!”)—made me a little nostalgic for Trinidad and hell, even calypso. It can, at least, be a lyrically clever music.

After the playlist looped a few times, I whittled it down to just two tracks—one from Atrocities and one that appears on both Atrocities and Awakenings—performed by a man who went by the not-too-humble stage name of Lord Commander. (Not that it’s an unusually bold name. Lord Commander, Lord Melody, Lord Kitchener, Lord Executor, Lord Beginner, Lord Pretender, Lord Observer, Lord Invader, Lord Shorty, and the list goes on: Trinidadian musicians of the nineteen forties and nineteen fifties borrowed freely and humorously from the titles of their British rulers.) Lord Commander—known variously as Mr. Action, Mighty Commander, and just plain Commander—is described in the Awakenings liner notes as having had an eccentric performing style. I suspect he earned this reputation by being—as Lord Pretender recounts in Hollis Liverpool’s oral history of calypso, From the Horse’s Mouth—among the first calypsonians to dance on stage. Apparently, Commander used to tap dance on street corners for money when singing did not earn him enough to live on. This additional talent didn’t serve him for very long: Commander died in squalor, rummaging the garbage bins of San Juan, Trinidad.

The sound of dripping water is so deeply engrained in the human unconscious that we might, in hearing a good recording of those drips, be brought back to our earliest memories as a species.

During his performing years, Commander was an eccentric and an incisive lyricist, and these qualities are easy to detect in “No Crime, No Law,” a song that inspired Derek Walcott to compare Commander’s brand of irony to that of the German poet Bertolt Brecht. I can’t speak to Brecht comparisons, but I do hear in “No Crime, No Law”—and even more so in his Atrocities track “You Can’t Finish Pleasing People”—not only an unexpectedly appealing form of the bouncing American rhythms that had by this time infused calypso (in both songs, Commander is backed by what sounds almost like a barbershop quartet), but also a hearkening back to the earthiness and unpredictability I miss in most calypsos. Perhaps it’s not so surprising to hear both sounds in songs recorded before Americans had fully taken their leave of Trinidad, and as the island began to seek independence from Britain. What is surprising—at least at first thought—is that I hear in these songs an anticipation of what was to emerge in the distant Bronx two decades later: rap—which takes as its oldest source the vocal arts of ancient West African griots, the wandering singer-poets from whose canards and incantations calypso, too, is widely understood to have emerged.

In “No Crime, No Law” and “You Can’t Finish Pleasing People,” Commander sounds in tempo and lyric as if he is barreling toward the Bronx in an ancient vessel. You can almost hear it in the lyrics to “No Crime, No Law”:

I want the government of every country

Pay a criminal a big salary

And when they commit a crime

The law shouldn’t give them any long time

A police should be glad when one twist a jaw

Lock a neck, buss a face, or break open a store

He should be merry when somebody violate the law

For that is what the government is paying him for

But if somebody don’t bust somebody face

How the policeman going to make a case?

And if somebody don’t lick out somebody eye

The magistrate won’t have nobody to try

And if somebody don’t kill somebody dead

All the judges got to beg their bread

So when somebody cut off somebody head

Instead of hanging, they should pay them money instead

It’s like a jungle sometimes.

In “You Can’t Finish Pleasing People,” Commander abruptly stops his rap-like cadences to shift—his voice even wavers and cracks—to a melodic barbershop chorus (that ends in a raucous line: “To hell with everybody!”), only to fall back into a careening rap. He sounds as if he’s straddling genres and eras; I can almost imagine him tap-tripping right and left across the stage as he bellows and sings.

Of course, I didn’t know or think about all of this as I listened to Commander over and over on New Year’s Eve, dancing around my living room until I was dizzy. What did begin to take shape in my mind that night was the idea that Commander held the same place in my imagination on New Year’s Eve that pirates held in the imaginations of the revelers at Catalina Island. Yes, Buccaneer Days is at heart an opportunity to get drunk. For those who took the opportunity a step further and made themselves physically uncomfortable for the occasion, there was something more going on. Something kinky, sure. But the woman bound to a tree—and her captor—must have found more appeal in the event than mere kinkiness can offer. I imagine that what they sought and found is a chance to locate the present in an image of the past.

Isn’t that really what I saw along the San Pedro channels—not the reassuring present, but an image of the industrial past? Steel, the ghosts of longshoremen? Isn’t that what I hear in Commander’s cadences, in my grandmother’s voice, in her sense of humor? Something old and essential. A griot, maybe, the one who whispered as I stood listening to Commander on the roof of my building at the turn of the year. This is where we are.

Suzanne Menghraj teaches writing in New York University’s Liberal Studies Program. “Buccaneer Days” is the second in a six-part series of essays Suzanne will write for Guernica with support from a Liberal Studies faculty grant. “Twin Peeks”, the series’s first essay, appeared on Guernica in February.