The big city of La Paz may be a draw for younger people in Sabina Ramirez and her husband Roberto’s village. But not for her. “I was born into a coca-growing family,” Sabina says, “and we’re going to keep it that way.” The Ramirezes live in a humble two-bedroom cinder block house in the village of Irupana, in the forest region of Los Yungas. Of Aymara Indian stock, Roberto’s eyes are constantly smiling. Sabina wears the traditional braid across her back, like most indigenous women from the area. Both show signs in their skin of a lifetime working under the strong Andean sun. Coca farmers in the crop’s heartland, they are a new breed of growers striving to change the image of a plant that has long been used for a very synthetic—and deadly—end product: cocaine. But the Ramirezes grow organic coca. And they’re hoping this can make all the difference.

Ever since the United Nations, in its 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, placed it alongside opium and derivatives such as morphine, heroine and cocaine, unprocessed, raw coca cannot be legally exported from Bolivia in any form. Article 49 of the treaty forbids the commercialization of coca or coca-based products, except for research or pharmaceutical purposes. However, the treaty’s imprecise wording has allowed a number of products that use organic coca as an ingredient to trickle onto the market in Bolivia and neighboring countries. If development of these products continues, it might help shift U.N. and U.S. attitudes towards coca as whole. If not, the subsequent fight between farmers and government agents intent on destroying the product could turn into another all-out guerrilla war, as took place in the 1980s.

Workers harvest coca in their field near the Afro-Bolivian coca farming community of Chicaloma, Bolivia. Photo by Roberto Guerra.

It’s late afternoon. The sun is just dipping behind the hills. Roberto walks us a few feet down the dirt path from his house, past banana and mango trees and clumps of overgrown weeds. He stops at a wide clearing from which we can see the face of the next mountain, a patchwork of green squares sprinkled with white-clad farmers harvesting on steep terrain. Divided into 40 or more steps, each a little over a foot wide, the Ramirez family farm is similarly perched on the side of a hill. This method, known as the “plantada,” has been used in Los Yungas at least since the Incas first used it to irrigate vertical farmland.

Roberto and Sabina prefer to grow their plants the traditional way, even if that means that they will bear fewer leaves, and in turn, generate less income. For the Ramirezes, coca isn’t only about money.

Roberto pulls a small leaf from a coca plant no taller than two feet high, and hands it to me. Waxy to the touch, the young leaf is the color of grass. It almost looks like a bay leaf, harmless enough; but I remind myself it has a much deadlier history. “Most of our plants are still too small to be harvested,” says Roberto. But because they’re grown free of synthetic pesticides, he continues, these shrubs won’t grow much taller by the time they’re harvested. Roberto and Sabina prefer to grow their plants the traditional way, even if it ensures they will bear fewer leaves, and in turn, generate less income. For the Ramirezes, coca isn’t only about money.

A cocalero from Los Yungas, walks through his family’s coca fields near Chulumani, Bolivia. Photo by Roberto Guerra.

Los Yungas is Bolivia’s epicenter of coca cultivation. For centuries, the plant has grown here alongside fruit trees and coffee; for just as long, it’s been consumed by the poor and working classes throughout the country. Most Bolivians consider coca a sacred, all-curing leaf. Chewing it—known here as doing the akulliku—helps keep you awake, suppresses hunger, eases muscle pain, gets rid of altitude sickness and indigestion, and serves as a mild stimulant, much like coffee. Sustained use is also believed to help prevent osteoporosis and diabetes.

But the akulliku is also a social glue, a ritual that holds together indigenous people here in South America’s poorest and most traditional country. Despite the UN’s demand that Bolivia phase out the tradition, the leaf is still chewed at weddings, anniversaries, religious ceremonies, and funerals; it is used by miners in the highlands near PotosÍ at more than 13,000 feet, by bus drivers crossing the country overnight, and by banana farmers in the eastern lowlands of Beni state, in the Amazon River Basin. In Los Yungas, from sunrise to sundown, cocaleros themselves nurse a wad of coca, or “bolo,” on the side of their mouths while they work. Roberto and Sabina, too, chew coca when they plant and harvest; they say it helps them work under the hot sun for long hours.

These violent showdowns between the military and peasants often resulted in human rights violations and deaths.

And whereas produce like avocados, bananas and mangoes can get easily damaged on the road to the market, coca can be stored for months without going bad and, for this reason too, it’s one of the most lucrative native crops in Bolivia today. In the last two and a half years, since the election of President Evo Morales (who also heads the coca growers’ union), the improved coca economy has allowed coca farmers to earn a decent livelihood. A fifty-pound bag of the small dried green leaves can fetch about $120 at a city market. For some of Roberto’s neighbors, income from coca is the only way out of poverty.

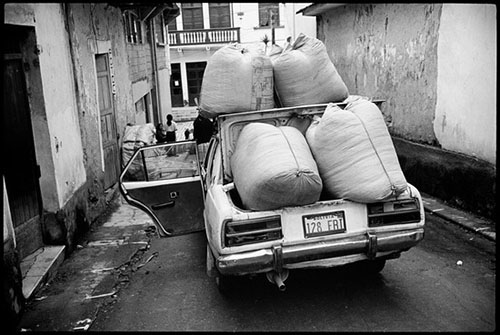

Coca is packed into 50lb. bags in Chulumani before being transported to be sold in the Villa Fatima coca market in La Paz. Here a taxi will take a cocalera’s bags to a bus departing for La Paz. Photo by Roberto Guerra.

Through the 1980s and 90s, a third of the world’s coca was grown in Bolivia. A significant proportion found its way onto the street in the U.S., as cocaine. Alongside Colombian and Peruvian coca, Bolivian coca remained—until very recently—at the center of the U.S.-sponsored war on drugs. The U.S. government exerted enormous pressure on Bolivia; in Los Yungas and the Chapare region in the east, the plant was the focus of alternative development programs which sought to replace it with other crops like coffee or bananas. When these programs were rejected by coca-growing communities, coca crops were then forcefully eradicated by the Bolivian army and agents from the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.

These violent showdowns between the military and peasants often resulted in human rights violations and deaths. The most publicized U.S.-financed model for coca eradication was introduced in 1998. Nicknamed Plan Dignidad, or The Dignity Plan, it was a strong-arm approach using both police and the military. It became synonymous with destroyed farms and violent attacks against campesinos. Roberto and Sabina agree that they avoided the worst of the violence during those times by keeping their activism quiet, and because their organic coca crops were small compared to those on neighboring farms. “During the Banzer dictatorship, showdowns between cocaleros and eradication forces were routine,” says Roberto. “We saw many people wounded, and sometimes even killed.” A few of their neighbors in Irupana were forced to leave farming altogether; many fled to La Paz.

As a result of the violence, and increasingly under Morales, emboldened cocaleros began seeking government support in growing the leaf to make products like teas, sodas, lotions and flour, hoping to combat the illicit trade of coca destined for cocaine production. President Morales threw his weight behind the campaign, eventually signing unilateral agreements with Venezuela and Ecuador which allowed the export of coca-based products. By making sure these products were free of the alkaloid stimulants in cocaine, Morales aimed to take advantage of the loosely-worded U.N. treaty and escape international sanctions.

Roberto and Sabina Ramirez, and thousands of others, are counting on this. In the complicated and ever-expanding coca economy, the Ramirezes are considered, however precariously, “legal coca growers.” They grow their coca in the traditional farming region of Los Yungas, certified by the Bolivian government to sell it at the legal coca market; and they’re expected to sell it for legal purposes only: as a raw ingredient for a variety of food products and cosmetics, or for the akulliku—though even this traditional practice has been controversial. (The 1961 U.N. charter grudgingly approves religious and traditional uses for coca, while encouraging the Bolivian and Peruvian governments to work towards a total eradication of chewing coca.) Though there are now many thousands of legal growers, what happens when the plants leave the farms can be out of the farmer’s control—unless the product is organic.

Sabina and Roberto sell their harvest directly to coca flour manufacturers from La Paz, who can offer them a little more money per fifty-pound bag than what they would get at the market. Non-organic growers, on the other hand, haul their bags after every harvest all the way from the villages in Los Yungas to La Paz, to sell them at the enormous, farmer-friendly Villa Fátima Market—set up by the government to prevent crops from being diverted to drug manufacturers. Unfortunately, it often seems to serve the opposite purpose.

The market is chaotic. Men flood through the doors into dingy hallways with enormous burlap bags full of coca on their backs. Women yell out prices, like brokers on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange, and haggle with customers. There are varying qualities of the leaf—from the least expensive tercera, or third best (small and generally brittle, not good for chewing) to the costlier elegida or “chosen one”—which is larger, fresher, and flawless. Organic coca, also known in the market as ecológica, is a rare find. When available, it can fetch even more than the prized elegida—up to $130 per fifty-pound bag.

Coca farmers pass the time at the Villa Fatima coca market in La Paz, Bolivia. Photo by Roberto Guerra.

Whether coca is organic or not is of little importance to Cyder, one of the market security guards. Wearing black clothes, knock-off Ray-Bans and a pistol strapped to his belt, he scowls at farmers as they come and go. “I’m just here to keep order and make sure business goes on as it should,” he says, eyes fixed on the entrance. “Things disappear here quite easily, whether it’s coca or money. People do transactions of up to three-thousand dollars in cash, and a lot of sketchy individuals like to do business in this building. So stuff can get lost.”

Cyder estimates that, despite the government’s best efforts, including ID badges required for growers and buyers, about half of the leaves sold here end up in cocaine labs throughout Bolivia. Finding out where the coca goes once it leaves the building is not his job, but that of police officers stationed on the building’s second floor. The men there belong to the Fuerza Especial de Lucha Contra el Narcotráfico—the Special Force Against Drug Trafficking.

When we try to find out what they do up there, we are asked, brusquely, to leave the market at once.

Days later, the Bolivian daily, La Razón, reports that on the same floor where Special Forces officers keep watch, men and women were getting paid to work as pisadores. Their job was to crush low-quality coca leaves—the first step for producing cocaine. Later reports quote Special Forces Director René Sanabria, as vowing to investigate.

It seems unlikely, then, that cocaine manufacturers would be willing to pay a higher price for organic cocaine when they have no need for quality produce. Instead, organic coca leaves are making their way into a variety of new products, produced by companies and entrepreneurs who, whether they know it or not—or even care—could change the coca market for good. And it’s the higher cost and the slower speed of growth that keep organic coca from cocaine labs.

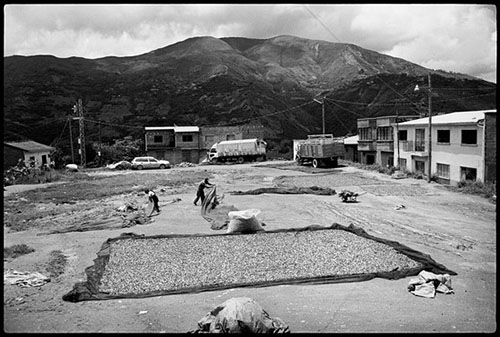

A recent harvest of coca dries for several hours in the sun in the remote community of Naranjani, Bolivia. Photo by Roberto Guerra.

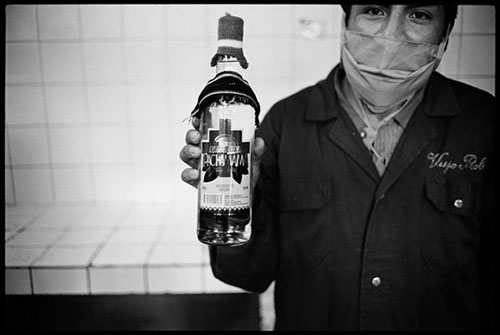

In a residential neighborhood fifteen minutes away from the Villa Fátima Market is the Viejo Roble warehouse. Outside, the building resembles a suburban two-story brick home—like others on the block. Inside, it’s a fully-functioning liquor factory, the pungent smell of alcohol in the air, about a dozen employees hard at work. In one corner, piles of coca leaves soak in large plastic containers full of alcohol, while a green liquid trickles into glass bottles, onto which an assembly-line worker sticks labels.

Complete with a well-stocked, faux wood-paneled bar, the upstairs office has the look of a 1970s living room; there’s wall-to-wall brown carpeting, glass tables, and a poster of a bikini-clad model sensuously groping a bottle of rum.

The coca shampoo bottle displays a picture of a beautiful blonde with flowing, healthy hair; its main ingredients are coca and natural oils.

Of all the different kinds of liquor produced at the factory, the most popular these days is “Pachamama”—a clear, vodka-like alcohol made with essence of organic coca. The 36 year-old manager of Viejo Roble, Adrian Álvarez, came up with the product name—a widely-used local moniker for the earth and fertility goddess.

“We launched Pachamama last year, and it’s been selling very well so far. It’s really popular at the bars here in La Paz,” he says, passing me a glass of the clear liquid, first mixing it with a splash of Sprite. He cracks a smile and stares a moment, awaiting my reaction. “Our slogan goes ‘Drink it when you’re feeling Bolivian.’ What do you think?”

It works. Not quite cloying, it has that distinct bitter, earthy flavor of coca. The result is a distilled, nicely packaged version of the akulliku for city folk, and, Adrian hopes, people outside Bolivia too. The name may help the product stay closer to the UN’s “religious and traditional use.” And it’s organic.

“I think coca is going through an interesting moment,” Adrian says. “Most people outside Bolivia still associate the leaf with cocaine, but they’re also curious about its traditional uses, and the fact that coca is increasingly being used in a variety of products.”

Every month, Viejo Roble buys half a ton of organic coca leaves from cocaleros in Los Yungas, and produces 15,000 bottles of Pachamama for the Bolivian market. Since earlier this year, the factory has started producing an average of 36,000 bottles for export to Ecuador, Venezuela, Colombia and Cuba. It’s a risky strategy. Álvarez is testing the international market, assessing the demand, and hoping the current legal loophole stays open. Pachamama is free of alkaloid stimulants the U.N. and U.S. have blocked. But that doesn’t mean Viejo Roble won’t still be targeted and shut down by international authorities. Yet Álvarez focuses on growth, he says; the company is getting inquiries from countries as far away as Belgium and Russia. And caution over the crop’s reputation doesn’t trump the bottom line. “Figuring our Bolivian slogan wouldn’t work abroad,” he notes, “we came up with this—‘Pachamama: Try the flavor of the forbidden.’”

A worker at the Viejo Robles distillery in La Paz shows the company’s coca liquor. Bolivian President Evo Morales hopes to expand the legal market in Bolivia and abroad for coca-based products. Photo by Roberto Guerra.

Prudencio Ticona is another industry leader who, willingly or not, is helping change coca’s story. For ten years, he’s owned Ingacoca, a small factory in a sprawling working-class slum right outside La Paz, called El Alto. The factory’s garage gives way to an office full of coca paraphernalia—product labels, posters for an organic coca fair, photos of Ticona with President Morales. There is a single phone in the office, no computer. Ticona is rarely here. He spends most of his time traveling Bolivia to meet organic suppliers, distributors and health food stores, vying for space on their shelves for his shampoos and health food supplements.

Unlike Viejo Roble and its savvy marketing campaigns, Ingacoca is a humble, do-it-yourself operation. Products are mixed in a back room a few times a week, using simple homemade recipes and containers. The coca shampoo bottle displays a picture of a beautiful blonde with flowing, healthy hair; its main ingredients are coca and natural oils. The adelgazante, or slimming tonic, contains coca with other traditional herbs commonly known as tipa and tarwi, both native to the Bolivian Andes. The green liquid is said to “metabolize carbohydrates and fats to eliminate obesity, purify blood and regulate cholesterol levels.” But there are no scientific studies confirming the efficacy of this treatment, Ticona admits.

His line of coca products is selling well throughout Bolivia. They’re available at health food stores and pharmacies, he says, and he’s getting requests from abroad too. “But generating interest in my Ingacoca products hasn’t been easy,” says Ticona. “I started producing my coca shampoos in the late 80s, when coca was really vilified and thought of mostly as the main ingredient in cocaine.” Like Álvarez, he believes that marketing coca for its health benefits, and to the right demographic, may be the only way to reverse coca’s reputation abroad.

Ticona has a wife and three kids, as well as a younger brother who works in the back room of the factory, mixing Ingacoca’s line of products by hand. He spends most of his time away from them, in his beat-up Toyota Corolla, its trunk full of samples. He’s been promised financial help from the Evo Morales government, he says with a flash of hope. But he has yet to see it. “Maybe the government feels that this isn’t a good time to formally invest in the legal coca industry,” Ticona says with a light shrug.

Almost 50 years since the U.N. Single Convention was signed, coca remains legally precarious, and—especially overseas—decidedly taboo. But back in Irupana, Roberto and Sabina Ramirez are trying to encourage other farmers to grow it organically. They’re betting on the continued industrialization of coca—and hoping that coca-based products will be sought out for export in coming years. A full reversal of international law would require Bolivia’s neighbors, the U.S., and Europe, to vote on behalf of one of the world’s poorest countries.

Ruxandra Guidi works as a radio and print freelance journalist. In the last year, she’s been reporting from Bolivia, Brazil, Peru, Panama, Venezuela and Mexico. Her work can be found at www.ruxandraguidi.com.

Roberto [Bear] Guerra is an independent photographer based in South America. His images, photo essays, and multimedia pieces on topics ranging from The Shipibo Indians of the Peruvian Amazon Basin to an emergency clinic in one of Rio’s most notorious favelas have been published widely. His website is www.bearguerra.com.

Guidi and Guerra’s reporting on coca in Bolivia was made possible by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting in Washington, D.C.