Part 2: Actor/activist Mia Farrow on the continued slaughter, China’s role, and what we can do to help the people of Darfur

The following Guernica program took place at PEN World Voices Festival of International Literature, on April 29, 2008, at Flourence Gould Hall in New York City. This is the second of three parts. To listen to the program in its entirety, please go to here. Runs about 90 minutes.

Dinaw Mengestu: Thank you very much, Mr. Lévy. Our next speaker this evening is Mia Farrow, who probably actually doesn’t need that much of an introduction. She has become one of our greatest advocates of human rights and is also one of our greatest and best known actresses. Mia Farrow has appeared in more than 40 films and has won numerous awards. In 1997, she published a memoir, What Falls Away. Ms. Farrow is also a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador and has worked extensively to draw attention to the plight of children. Ms. Farrow has traveled to Darfur eight times to advocate for an end to the crisis there and has published multiple op-eds in the Wall Street Journal and the LA Times. Her website miafarrow.org focuses on the Darfur crisis. Here is Mia Farrow. (applause)

Mia Farrow: Thank you, thank you very much. Thank you to Guernica. Thank you to PEN. Thank you Bernard Henri-Lévy for sharing what you have witnessed. It is impossible not to be shaken by what we hear from you. I have recently returned from my eighth journey into the Darfur region of Sudan. Incomprehensibly, more than five years have passed since the government of Sudan and its proxy killers, the Janjaweed, launched their campaign of destruction upon the non-Arab population of Darfur. Only the perpetrators dispute that hundreds of thousands of men, women, and children have been slaughtered. It is all the more appalling, as you have said, that we cannot count the dead. The UN figure remained at, hovered at, 200,000; for two or three years, no one died in Darfur. And suddenly people are saying probably half a million. Our Sudan expert has said it’s in excess of half a million. But we don’t know and the travesty and disrespect of that is beyond comprehension.

But also in keeping with what we know about Darfur, one of the first images that preceded this said “Never again.” After the Nazi Holocaust, the world vowed never again. How obscenely disingenuous those fine words sound today. We see Sudan. It is the largest country in Africa. The Darfur region, as you see, is in the western part of Sudan, the darkened areas. Note the borders. Note the borders with Chad and the Central African Republic, because they are completely porous or nonexistent. Villages literally straddle the borders and eastern Chad is an inferno, as is the northeast corner of the Central African Republic. Many people ask why? And I’m just going to fill that in a little bit so that we don’t have to cover that later.

Oil was found in the south part of Sudan, many years ago. There was a war that waged for two decades, as Mr. Lévy said, in which some two million people died. The west intervened and sponsored, eventually, the North-South Agreement which was signed in 2005. Oil revenues were to be shared and southerners were to have significant representation in the Khartoum-based government. But the Darfur region was left out of that agreement, left essentially in the dark ages, where the British had left it when they left Sudan.

In 1956, they left it and they left governance to an Arab government in Khartoum. They favored the Arabs. The people in the Darfur region are non-Arab. In 2003, some young men formed a rebel group and there was an uprising in the center of the Darfur region. They incinerated a couple of planes, they killed some government soldiers and in response to this uprising, the government of Sudan launched an all-out assault upon the civilian population of Darfur. The justification for attacking civilians in this manner was that civilians were the base of this rebel movement. The people of Darfur, they wanted hospitals, they wanted compensation, they wanted representation in the government, they wanted schools, they wanted electricity, they wanted to be included.

Of course there was an uprising. But the slaughter that followed is what was wrought… The word Darfur is now synonymous with suffering. I took these pictures over my eight trips into the region. What you see here is a typical village in Darfur in the year 2004. You see mature fruit trees, walled gardens. There would be animals, and despite the arid soil, people have sustained themselves through the centuries through agriculture. It is an agricultural community.

Same village, 2006. 80-90 percent of Darfur’s villages are ashes today. The ashes of the village of Tamadjour, the village that you saw first, really is notable for the fact that it existed. No longer. I met Mr. Joseph Omar going through the still smoldering ashes of his village searching to find anything that could be of use to those members of his family who survived the attack. There was a tiny group of people huddled a few kilometers away, dazed, terrified, surrounded by their attackers. Not knowing which way to turn without food, without water. Mr. Omar returned at great peril to himself to try to salvage something, but really found almost nothing…a pot and a lid. The food was gone, the village was gone, children had been thrown into burning huts, people had been mutilated, women had been raped. Two and a half million people have been driven from villages such as the first picture you saw, into camps, such as this…

This is Kalma Camp in West Darfur. I took this in 2004 from a helicopter, and it was my first sighting of an internally displaced persons camp. If a person is in their own land, they’re not a refugee. The technical term is “internally displaced person.” They are displaced people and what you are seeing here is sheeting lashed to the desert floor. Not a tree, nor a blade of grass, nor scarcely a shred of hope. The lack of trees is significant because where the camps are, there are no trees and whatever shrubbery had existed would have been used to build fires. The world food program distributes sorghum. Sorghum requires more than two hours cooking on an open fire and fire requires wood.

As you can see from this camp of 90,000 people, there was no wood. This means that the women—and the population of the camps are primarily women and children—they have to leave the relative safety of the camps, and I say relative because the camps themselves are continually attacked. The camps are cauldrons of despair and rage. And people have to leave to get the firewood. As of June 2006, when I encountered a UN assessment team, the average deforestation around the camp was ten miles. Obviously considerably further today. Meaning, a woman had to travel an excess of ten miles, being exposed for twenty miles, to attacks, mutilations, abductions, rapes, by what Mr. Lévy has told you [about], Janjaweed. Literal translation: evil, or devils on horseback.

They encircle the camps and pick off women who leave the camps. This is—I couldn’t capture the size of this camp—it is the largest camp in the world. It is Garetta, 175,000 (people). It is near Nialla, and because of the attacks on aid workers, there were only 7 aid workers, no doctors, no medical personnel, addressing the needs of 175,000 human beings. The getting of the firewood, I took this (photo) in 2004 when you would see donkeys in Darfur, it is the Sophie’s Choice of who will get the firewood today. In this case, an older woman chose to spare her daughters the danger and horrors of (it), and in an Islamic culture, a Muslim culture where the victims of rape are held culpable. As horrific as rape is to us in our culture, it is a thousand times worse for a Muslim woman. Behind the woman you can see, it looks like an airplane, but actually it was an attack helicopter of Darfur going about the grim business of bombing the villages.

Getting the firewood. I have to say that, more often than not, I could not bring the camera to my eyes to take the photograph. My sisters in Darfur showed me their mutilations, the branding of when they were raped, the tendons sliced in their legs, so the markings of when they were raped how they had to hobble now when they went to get the firewood, breasts burned. I felt then two things. One is, I should not be taking this picture. And the overriding one is that I am a witness of these atrocities and it should not be easy to turn away. The women wanted, they asked me to tell our sisters in my country what is happening to them. I have around my neck, actually, a hijab, a necklace with a piece of the Koran. A woman named Halima gave it to me in 2004. She insisted that I have it for my protection. I, who could offer her no protection. She had been wearing it on the day her village was attacked and she had been holding her infant son who was torn from her arms and bayoneted before her eyes. Three of her five children were similarly killed on that same day and her husband, too. “Janjaweed,” she said, “they cut them, and threw them into the well.” And then she clasped my hands and said, “Tell people what is happening here, tell them we will all be slaughtered.” And I, if my moral mandate wasn’t clear by that moment, it was certainly clarified from that time on. And unfortunately, Halima’s story is identical to the stories of countless women I have met on my journeys into the region. The stories of this woman when she was raped. She said she was raped by twenty to thirty men. And they put firesticks out on her body as they raped her and also they called her the worst kind of racial slurs, and said, “Now you will give birth to a light-skinned child.”

The camps. The camps, after five years, you can see the sheeting handed out in 2004, has disintegrated, and people are now using the last line of defense, which is their blankets. The relentless sun, the rainy season, the sandstorms, have ripped the sheeting to nothing and it’s disintegrated. And people shelter there, under the blankets. But I have to say the camps are so unsafe that humanitarian work is grinding to a halt.

Last December, Oxfam, the head of Oxfam in Sudan said, read this: “Our staff are being targeted on a daily basis. They are being shot, robbed, beaten, and abducted. The security situation is the worst since the conflict began. These are not conditions we can keep working in. Attacks on aid workers rose 150 percent in the last year. The region has become so dangerous that an unprecedented two million people are now out of humanitarian access. We don’t know where they are. We don’t know how they are.”

UNICEF reports that in many or most of the camps, thirty to fifty percent of the camp is suffering from acute malnutrition. Acute malnutrition. This is what acute malnutrition looks like, in case you haven’t seen it. Acute malnutrition. And in the face of acute malnutrition, last week the world food association announced that it had cut its food rations going into Darfur by half. Because it is too insecure to deliver by the roads, and the airdrops are unsustainably expensive. So what little people were getting has now been halved.

Saroya Adom, my friend, I see her whenever I go to the region, is twenty seven years old, and I think in her face is all of Darfur. She walked for 22 days to reach a camp on the borderland in Eastern Chad, but when the village was attacked first by bombs, then by Janjaweed, she gathered her children and tried to run and she never saw her husband again. And two of her children died on the long walk. She said she ran, and someone said there was a country called Chad. And she didn’t know where it was and she kept asking people, “Do you know a country called Chad?” And eventually, she ended up in a camp but two of the children…she told me the agony of not being able to bury the children. That she could only scratch the sand to cover her children with some sand, and had to move on because the children were dying.

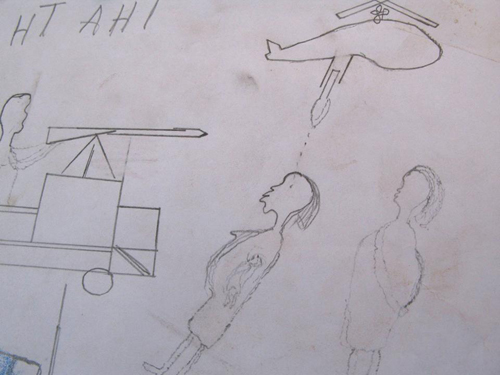

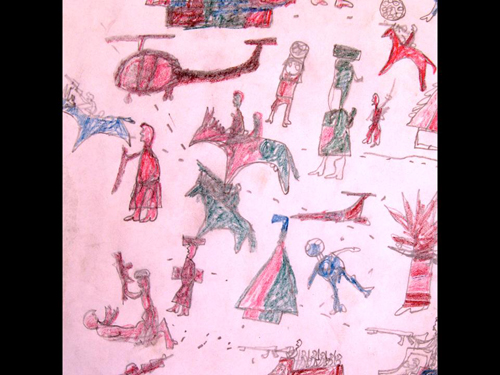

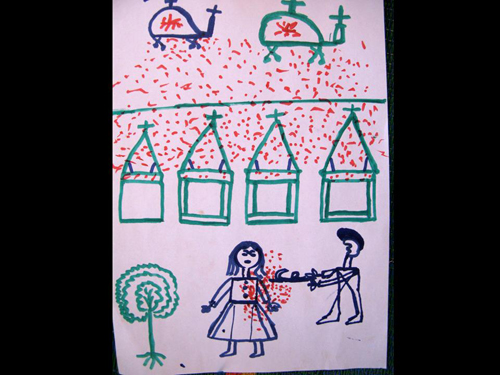

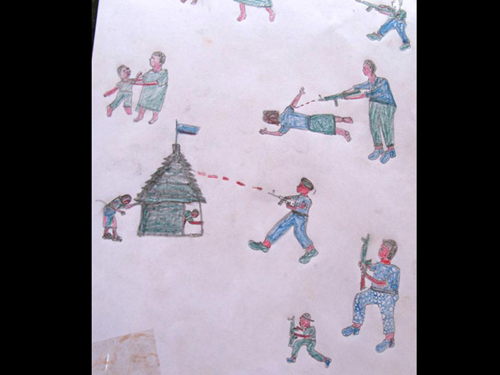

The attacks on villages, or the accounts of those who’ve survived the attacks are numbingly similar. Morning, always the morning. The morning skies fill with bombers and attack helicopters, raining bombs upon homes and families as they sleep, as they pray, as they prepare breakfast, as they are going out to the fields. Here you see children’s drawings. Children gave them to me in what are called child-friendly spaces in the camps. Children are allowed to draw whatever they want and so often they draw the day that changed their lives. And they’ve given me these pictures and I’ve given them to the holocaust memorial in Washington, but I’ll share some of them with you because they depict very vividly what happened to them. The houses were on fire, the bomb ships dropping bombs. This child drew her mother cooking breakfast and the men, the Janjaweed with a machine gun, shooting her. And she, the child, running. People running, being shot as they run, women, children, without discrimination. People shot, people raped. This helicopter is dropping bombs on this child’s pregnant mother. You can see the fetus inside her.

This very complex picture, in the lower left hand corner, is a picture of a rape.

The people of Darfur have been and continue to be slaughtered, yes. But they are also dying and continue to be, dying in the camps of disease and hunger. Women die of humiliation and shame. They die of despair that they will never be able to return to their homes. They despair because their losses are too numerous to count, or ever reclaim. They despair because five years of terror is too long. And here you see people begging for mercy, people trying to gather their children, people hiding. Unimaginable terror.

And this woman showed me the bullet wound in her back. She had been running for her life with her child on her back, and the bullet passed through the baby, killing him. But she says the wound in her heart is the wound that causes her to weep everyday; the loss of her child. This group of people was running across the sand and I happened to encounter them a week in November in Chad, last November when fifty villages were attacked. The Arab militia, the Janjaweed, crossed over the border into Chad, and attacked the non-Arab villages in Chad. Thousands of people were killed and behind these screaming children was their burning village. People, if there was any warning, gathered what they could and carried their things on their backs and they were just, they didn’t know which way to turn or where a camp was. Groups under trees with little to nothing and surrounded by their attackers. These groups you see don’t even have mats to sit on and they are primarily women and children. These people in Chad were identical to what we saw in 2004 and 2003 in Darfur. We knew it would cross over into Chad, yet we did nothing and now Chadian villages are ablaze, Chadians are displaced. And those Darfurians who fled into Chad, 250,000 of them, they too are now fazed. This woman and her two children were thrown into their burning house. Her heart is now empty. They are sitting under a tree, beyond grief and and an older woman is taking care of younger children, a very familiar sight. They were not her children, she didn’t know (them), but she said she would take care of them.

Grief. This was an older woman, sitting under a tree, her village was burnt, her loved ones were killed and she was weeping and I could offer her no comfort. I held her in my arms.

Janjaweed. Very dangerous players in a very dangerous terrain. Janjaweed leading an attack on a village. In the tiny town of Cosbeda, three men lay side by side, their eyes cut out by Janjaweed knives.

The tiny medical clinic, there was one doctor trying to address trying to meet the needs of perhaps a thousand people pouring out of the seven room clinic, three men. And this child stood to defend his village with a bow and arrow which was no match for a machine gun.

He died, when I came back that night, I was happy that he had died, because there was no pain medication for this child and he was in agony. The children.

I think the children speak more eloquently than I possibly could. “No food nine day,” said this boy.

At the end of the day I had filled my empty water bottle with what the children were sucking from the mud, sucking from the swamp water. That was the water they were drinking, and that was my clean bottle of water. This child is one of the many child-headed households in the camps.

Her parents died and she says, she is now the mother of her little sister and she was defiant in saying that no further harm would come to her little sister, but the baby has not uttered a sound since the day their village was attacked. It is a traumatized population. This little girl, her parents were killed the day before.

A dying child, a child of hope.

Actually, this child is my screen saver, on my laptop. My personal family, we are for the most part not related by blood, but much more important, we are related by love and I tell my children, when one of us is suffering, we all suffer. And when we turn away, we are surely diminished in the most essential way. And this is our child, and is deserving of protection and in truth, I don’t know if she’s still alive. I took this in 2004. Even above the desperate need for water and for food; the plea for protection, from across Darfur and Eastern Chad, from every camp and village. This is what reverberates in my soul.

I don’t think there can be a more visceral plea from the human heart than “protect us.” What message, after five years, what message have we sent to the people of Darfur? These are the victims of our indifference; the only message we have sent is that they are completely dispensable. There is some larger game of monopoly and the people of Darfur clearly are simply expendable chips. Next month I will return to the region. People will again tell me their stories. Again I will write down every word. I will take more pictures. I will hold broken women in my arms and again I will promise them that I will indeed tell the world what is happening to them and then somehow I will leave them there in that hell, and I will come back to a largely indifferent world. What is needed now and for future genocides, I don’t flinch at the word, is the will of the international community to accept its responsibility to protect those civilians imperiled by genocide, ethnic cleansing, whatever you want to call it, mass atrocities. The UN has called it “atrocities of the worst kind.” A responsibility unanimously accepted by the United Nations in 2005, but with words proving to be as hollow as “Never Again.”

Under intense pressure, Beijing has hired two international press firms to sanitize their image and … they did appoint an envoy to Darfur, and they did sign on to a new UN resolution last July to provide 26,000 peacekeepers.

And I cannot conclude without mentioning China. As Bernard Henri-Lévy has mentioned, genocide, Sudanese style, is expensive. It requires the purchase of bombers, attack helicopters, and a steady flow of arms and ammunitions. Some seventy percent of Chinese oil revenues, which now top 4 billion U.S. dollars a year, are used to attack the non-Arab population, the civilian population of Darfur. And the vast majority of weaponry used to attack civilians is of Chinese origin. But there is one thing that China holds more dear than its unfettered access to Sudanese oil at this moment in time. That is the successful staging of the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games. This has provided us with a window of opportunity to weigh in. Under intense international pressure, Beijing has hired two international press firms to sanitize their image and, for the first time, significantly, they did appoint an envoy to Darfur, and they did sign on to a new UN resolution last July to provide 26,000 peacekeepers to the region. But a scant 9,000 have deployed and they are placing every conceivable obstacle in the path of an effective deployment of that force. For five years, our governments have watched the slaughter in Darfur and they have failed to take action so an unprecedented phenomenon is emerging. Individuals are taking up the responsibility to protect and we see scores of U.S. congressman, European parliamentarians, Nobel Prize winners, philosophers, intellectuals, sports figures, students, ordinary people all of them, stepping up to protect this agonized population of Darfur and to urge each of governments and China to reassess its no-strings-attached support of abusive regimes, not only in Darfur, but around the world.

What can we do? Urge our governments to boycott the opening ceremonies of those Olympic games. I don’t know how you feel right now, I don’t care what President Bush does next year, but this year, he is representing the American people and if you feel that you don’t want him at the opening propaganda, do call the White House. There is a 1-800-Genocide number set up by a representative of Genocide Intervention Network, and they’ll put you right through to the White House. And as we’ve talked about sanctions, make sure your own money isn’t in any company such as Fidelity, which is actually invested in Petro-China, which is supporting the genocide in Darfur. So make sure you have a clean account. If you go to my website under “What We Can Do” it will give you a website number, so you can check where your holdings are. I think most people don’t want their own money killing innocent people. Bottom line is, if Beijing elected to act, our country and Europe, nations of the world have very little leverage over the government of Sudan, (China) has immense leverage through its business relationship with Sudan. So if Beijing elected to act, rather than talk, it could use its influence to demand that the regime call a halt to the ongoing aerial bombardments and ground attacks of civilians. And China could demand that Khartoum cease to obstruct the peacekeepers. China could refuse to sell weapons to Sudan. How can China host the Olympic games at home, while underwriting genocide in Sudan? The two, I’d say, are obscenely incongruous.

We look at Rwanda and we despair at our own inaction. When the history of this terrible episode in human destruction is finally written, will we have any less reason to despair? Our country, the U.N., all the nations of the world, failed the people of Rwanda, as we are failing the people of Darfur, and we are failing our most essential selves. Elie Wiesel wrote, I will end on this note, “The victims of the Holocaust perished, not only because of the killers, but also because of the apathy of the bystanders. What astonished us, after the torment, after the tempest, was not that so many killers killed so many victims, but that so few cared about us at all.” I’d say it is a defining moment for each of us as human beings where we come down on this, when, and under what circumstances, will we act? Thank you very much.

Check back in August for Part 3, where Dinaw Mengestu asks Lévy and Farrow what makes them so sure China can make a difference, and what next if the Olympics don’t yield the Chinese pressure activists have sought to end the genocide.