In May 2007, a minor retrospective of the works of the Iranian-Armenian artist, Sonia Balassanian, was shown in Tehran’s Aria Gallery. For an exiled artist displaying work that would have previously been deemed too political, too critical of the regime, this event should have been a homecoming. It didn’t work out that way, of course.

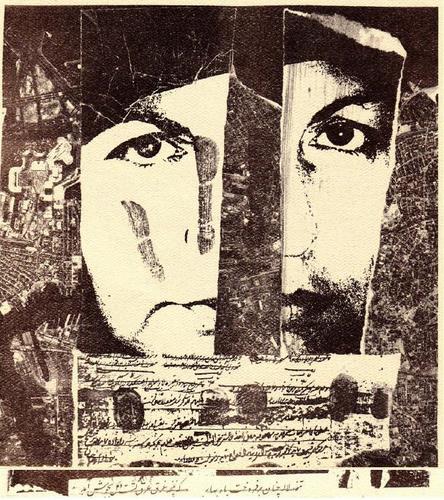

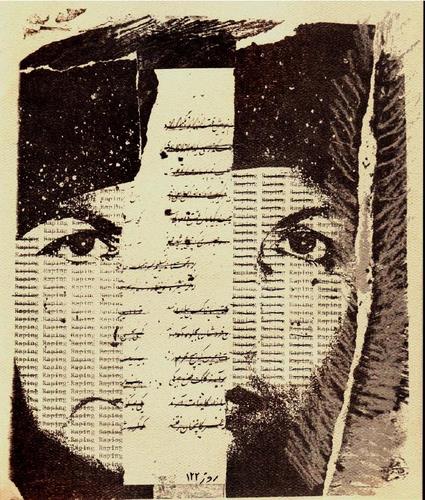

Balassanian had been part of a thriving community of Iranian artists before the Islamic Revolution. Yet because of the new regime’s initial hostility towards art and artists (not to mention Balassanian’s Christianity), she, like many of her contemporaries, ended up emigrating to the United States. In the 1980’s, as the Iran-Iraq war roiled the Middle East, Balassanian’s work in the U.S. became progressively more political. In 1983 she produced Portraits, a series of headshots of herself, wearing the hejab. Balassanian took one image and repeated it, but altered and distorted the photograph in a slightly different way each time. In the end the image is not recognizably her, but more a kind of everywoman-one whose partially veiled face appears fractured and tattooed with Persian calligraphy, along with the English words “raping” and “stoning,” repeated over and over again.

This work was at least a decade or more ahead of its time. By the mid-nineties, the fully cloaked or partially veiled figure of the Middle Eastern woman was something of a staple in Western art galleries and glossy magazines. Balassanian’s work used that imagery but in a subversive way, long before the “otherness” of the Islamic female figure became a fashion statement.

It is as if the subject in the photographs is both a witness and a casualty of the devastation that the Islamic revolution has wrought.

In the summer of 2005 I caught up with Balassanian in Yerevan, Armenia, where she spends part of the year and, along with her husband, directs the Armenian Center for Contemporary Experimental Art (ACCEA). Now in her mid sixties, Balassanian continues to insist on the transforming power of art with a refreshing lack of cynicism. Her intonations, when speaking Persian or English, sound like unhurried question marks. In that same voice-over many cups of potent Armenian coffee in Yerevan-she told me how one of the intentions of the ACCEA is to broaden cultural dialogue between the inhabitants of a region who have traditionally known each other mostly through hostility. Toward this end, the ACCEA produced a traveling show featuring artists from Turkey, Armenia, Georgia and Iran. Some of Balassanian’s work was included in this collection, and ultimately the show was successful enough that she was asked to commit to that solo exhibition in Tehran.

A book version of Balassanian’s Portraits—produced back in the 80’s, in New York—was going to be reprinted to tie in with the exhibition. She asked if I would write the preface. Agreeing should have been a no-brainer, but I was hesitant at first. This was overtly political work that was to be displayed in Tehran, after all. It had been produced in exile, during a particularly dark period following the revolution. The recurrence of the splintered frontal shots of the woman in the headdress, holding the onlooker’s gaze, suggest tragedy not just for one woman but for all women. It is as if the subject of the photographs is both a witness and a casualty of the devastation the revolution has wrought. More importantly, aside from the Perso-Arabic calligraphy, the appearance of those specific words-“stoning” and “raping”-is a deliberate and not-so-subtle reference to the now religiously sanctioned practices of stoning an adulterous woman to death, and raping any virgin that has been sentenced to execution. There were some very young female political prisoners during and after the revolution. These practices were routine when Balassanian was making her art.

And yet there is another dimension to the use of those words: “stoning” and “raping” were not only repeated in many of the pictures, they were repeatedly crossed out as well, as if the acts never took place-hinting at the practice of denial, of changing the historical narrative, of the ease with which those in positions of power can make evidence simply disappear.

I did, of course, end up writing that preface. At the end of the text I wrote that the portraits “…are here to force us to remember, and to remember hard. They demand that we hold this woman’s gaze, even though the proof of what befell her has been whitewashed, crossed out, put aside, and mostly forgotten .” And even though I could not be in Tehran for the opening of the show, I was curious to know how it would turn out, how people might respond. In the end, though, I might have known what would happen.

The portraits never made it into the exhibition. They were put up, at first, and then taken down again. Other, more benign works by the artist survived the opening of the show, but not the portraits. The directors of the gallery suggested that the work was too provocative, too risky. And maybe that justification, in the context of an art show of politically motivated work in Tehran, is not without some merit. After all, this is a place where official wrath over “offensive” work can be quite real.

Imagine a museum devoted to a disaster where no indication, no proof of the disaster itself is allowed to be present.

In the meantime the evidence did indeed disappear, again.

So what did the show look like? We are forced to resort to that uncensorable resource of the artist: the imagination. Imagine, then, the woman’s gaze on the walls of a gallery near the corner of Valy-Asr and Beheshti Avenues in Tehran. Now imagine the empty walls after she has been relegated to the dark storage room, where no one will see her. Then imagine a show devoted to a disaster where no indication, no proof of the disaster itself is allowed to be present. You have arrived; you are at the corner of Valy-Asr and Beheshti Avenues in Tehran, where you can rest assured that nothing contrary is ever put on display, and where memory itself vanishes.

Salar Abdoh‘s latest novel is Opium. He can be reached at zzsalar@aol.com. Click HERE for Part One, “Moving Violations”, in his series on Iran. Click HERE for Part Three, “Irrational Waiting”.