ACEH: There is no “Ground Zero” in Banda Aceh – no single point which can be defined as the epicenter of disaster. A tremendous wave leveled entire neighborhoods to the ground. Closer to the coast, what remains of the city has a striking resemblance to the old black and white photographs of Hiroshima after the devastating nuclear explosion.

Hundreds of mass-graves have not been covered.

People are cautiously returning, searching for bodies. In the neighborhood of Puekan Bada, the smell of decomposing flesh is unbearable. Bodies are everywhere, buried under the rubble and dead trees, or simply floating in stale water. After one month in the water, bodies are unrecognizable. Flesh is almost gone; hardened skin is tightly attached to the skeleton.

Bodies – some in yellow and blue plastic bags, others exposed to the sun – are resting on the bottom of deep pits. Heavy equipment: bulldozers, excavators, and trucks are idly parked just a few meters away. There seems to be no lack of machinery or fuel, but almost no organized effort to put it to use.

Jamaludin, a forty year old man, is searching through the rubble, machete in his hand. He lost almost all members of his family. Now he sleeps in one of the refugee camps at night. “TNI (military) set up several camps in the area, but they abandoned us a few days later. Government sometimes delivers water, but it is not clean. Several people that I know have stomach infections; severe diarrhea.”

He guides me through the rubble to the body bags. “We don’t know what to do with them. We have no shovels ourselves, but according to the Muslim tradition, bodies have to be buried. Some gangs visit this area at night, burning the bodies with petrol. That’s absolutely wrong, but there is nothing we can do – it’s unsafe and horrifying to stay in this area at night!”

The government has declared that victims will not be allowed to rebuild their houses 2-3 kilometers from the coast. Those who survived the tsunami are supposed to be relocated (“for safety reasons”), but no concrete plans have yet been presented. Local people believe that the government and big businesses are planning a “land-grab” in potentially lucrative areas close to the coast.

Mr. Syamsuddin, one of the former inhabitants of Lamteungoh village sums up the frustration of the local people: “The government tells us that we cannot return to our homes if they are closer than 2 kilometers from the coast. We all know that this is the best land. But the government and the businesses don’t want to pay anything. They are just promising to relocate us. Once we are gone, they can develop this area into an industrial zone or build hotels, golf-courses, anything… For them this is a great opportunity to make money; they are taking advantage of this disaster and our suffering. This is still our land! If they will compensate us fairly, we will accept. If not, we will stay and fight!”

According to Mr. Syafruddin – coordinator of CARE ACEH, a local humanitarian NGO – the government is not planning to give any compensation to the victims of the tsunami. “They (the government) say that the refugees will be relocated; their houses rebuilt somewhere else, but no location has been designated so far, and there is no exact budget. Given the government’s track-record, we are afraid that most of the funds will disappear. Care Aceh is advocating for the rebuilding of houses at their original location.”

INADEQUATE RESPONSE

There is hardly any doubt that the government in Jakarta failed to respond promptly and adequately to the natural disaster which can only be described as one of the most devastating in human history.

Hours after the giant tidal wave killed more than 200,000 people, the government of Indonesia made no coordinated effort to launch a massive rescue and relief operation. Only six transport C-130 airplanes were mobilized and even these were not ordered to take off immediately (Banda Aceh airport was damaged, but not the one in Medan, from where the aid could have been transported by land).

Instead of declaring a national state of emergency and mobilizing private airliners and ships for relief operation in Aceh, the government advised the citizens to pray for the victims. Jusuf Kalla, Vice-President and newly elected head of Golkar Party (the same political force which ruled the country during Suharto’s dictatorship) decided to use precious space in C-130 planes to fly “volunteers” – his supporters from several religious movements like MMI/Majelis and FPI – for his own political goals.

Maulana Ibrahim, a youth leader from Aceh assessed the work of these volunteers: “We saw hundreds of volunteers coming to Aceh just days after the disaster. They arrived from Jakarta, Yogyakarta, and even Pontianak. Almost all of them were amateurs, unable to work in extreme conditions. They themselves were depressed and horrified, unable to lift spirits of local victims. Some doctors couldn’t handle these conditions and abandoned their post after two days. The government gave them no maps; they did not know where to go, did not know names of the districts… Logistically, their presence was a total disaster.”

Mr. Asraw, coordinator of PCC (People’s Crisis Center – arguably the most active humanitarian NGO in Aceh) described volunteers from Jakarta as: “people who complicated the situation even further. They were taking photographs of dead bodies, looking like tourists. Some volunteers were just government spies, although after the Martial Law, one would wonder why the government needed more of them… My conclusion: most of the volunteers did close to nothing.”

“It’s not only that government forces did almost nothing”, continues Mr. Asraw. “In many cases they were preventing aid from reaching the refugees. We know about corruption cases, like the one in PEMDA, district of Dewantara in North Aceh, where local government, instead of giving urgently needed aid to refugees, passed it to the local military commander. Even here in Banda Aceh, military was selling aid supplies through warungs (local shops). PCC office had been visited by the military on several occasions – they were demanding food and water. They were very rude. Once, our worker asked them to fill out the papers – normal procedure. Soldiers got angry and began kicking and destroying huge, and then so precious bottles of water.”

Almost all relief agencies working in the field agree that approximately 70% of the aid came from abroad. Locals are scared of the moment when the international community will decide to pull out of Aceh. There is graffiti all over the province, asking in English: “Please help us!”

From the very start, the Indonesian government didn’t try to hide the fact that helping Aceh was not on top of its agenda. Just a few days after the disaster, the Minister of Finance declared that nation’s economic growth would not be seriously affected, because Aceh is in the exterior parts of Indonesia. He also noted that reconstruction efforts would be financed mainly from abroad.

All those who suffered were mostly poor Acehnese. Natural gas and oil production (controlled mainly by multi-national companies) detected almost no disruption. “It’s remarkable”, commented Deddy Afidick – executive of EXXON/MOBILE, seated in his luxury villa – far away from the disaster area – in Banda Aceh. “Our oil-fields suffered no damage. We can speak about zero damage! And the same goes for our friends at LNG – no destruction at all!”

THE “FIRST TSUNAMI” REVISITED

Away from the coastal areas of Aceh, there is no destruction. Road passes through pristine countryside. Green fields, sleepy villages and high mountains in the distance. All this looks like a stereotypical image of earthly paradise taken straight from some tourist brochure. The only disturbance comes from armored police and military trucks, driven at head breaking speed, premeditatedly pushing all other vehicles off the road.

But behind the facade of this pristine beauty, there are military and police check-points in every village. And in almost every house – misery and often hunger.

On the advice of one of the local NGOs, I drive to the area of Desa Siron; to the old village of Keureung Krung. All houses are traditional, made of wood. The entire village runs towards the car – to welcome me. I ask about the refugees. There are several families who managed to escape from the devastated areas on the coast.

“These children lost their families. Their relatives were swept away by the sea,” explains an old woman with a wrinkled and exhausted face. “We received no aid from the government. There is nothing we can do; we went to Lambaro and talked to the government officials. They gave us nothing; they sent no people here. We were trying to talk to the District leaders, but he refused to see us. Nobody cares, especially the government. We need food, we need medicine; we need some help for children who experienced terrible trauma. We are so angry! People in this village are feeding us. They are the only ones willing to help, but they have almost nothing themselves!”

After some hesitation, a group of elders decides to approach me. They need to speak to me, they say. We enter a small, humble mosque and seat ourselves on the floor in a circle.

“You are the first journalist who ever came here”, says the village chief. “Nobody ever visits this place; we are cut off from the world. Military comes here several times a week, always at night. They torture us and they beat us; we feel humiliated and desperate. Military asks the same question: “Where is GAM (Free Aceh Movement)?” They give us no time to answer; they begin beating us, putting our head under the water until we can’t breath. They even beat women. We heard that military was supposed to help the Acehnese after tsunami. But they do the same things to us now as they did before.”

“They usually arrive at 3AM; four or six of them, riding Honda motorbikes. They are from “Pasukan Raider” (“Raider Troops”), but they have no name tags. All we know is that their leader’s nickname is Ampah.”

“Once I was tortured so brutally that I couldn’t move for hours, afterwards. We are not brave to fight back – they have guns and we are not armed. And they seem to be drunk, or maybe insane. They torture our elders, even one blind man from this village. They just enjoy doing it! They shoot our animals, shooting cows with machineguns, point blank. They destroy houses and prevent us from tending to our rambutan trees, cucumber and rice fields… They break our fences, so the wild animals can get in and domestic animals can escape.”

“They killed almost 20 men around here, some 5 months ago. There was no battle, no confrontation. Only few of those killed were members of GAM; the rest were just villagers – bystanders. We don’t want the Indonesian military around here! We have had enough; we can’t take it anymore! This is happening all over Aceh; not only in the villages here, but everywhere outside the major cities!”

“When GAM fighters come here, they never treat us like this. When they visit their family here, they always bring food with them. They always come alone – humbly. And they never carry guns when they come home. But the Indonesians? How can we ever make a deal with Indonesia? How can we even talk? They never listen to us. They just beat us; torture us before we can say anything! People here say that Aceh has been hit by the second tsunami. Our first tsunami was the imposition of Martial Law in May 2003!”

POSITION OF GAM

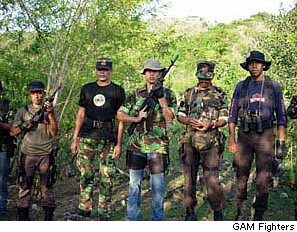

After some complicated security maneuvers (meeting local guides and exchanging passwords), I am taken to one of the military leaders of GAM – commander Nasir – who is in charge of the area of Banda Aceh and Aceh Besar. I have to climb a steep rocky mountain, before encountering two fully armed fighters, who escort me to their commander, a forty year old man with a mustache and firm handshake.

Although we are in the middle of the wilderness we take our shoes off, seating ourselves on a straw mat.

Peace talks between the Indonesian government and GAM just collapsed in Helsinki, Finland. The government refuses to even discuss the possibility of a referendum, fearing that the Acehnese people would overwhelmingly vote for independence, as people in East Timor did. The last time the bilateral talks between the two sides collapsed, fighting erupted and countless lives were lost.

After the tsunami both the GAM and the government declared a ceasefire, but since then, the Indonesian government and the military have accused GAM of igniting a new wave of violence and sent out a security warning to the members of the international community, active in Aceh.

Most of the foreign workers in Aceh discount such government warnings as baseless. GAM has said that it has never considered attacking foreigners. Instead it accuses the government and the military of taking advantage of the post-tsunami chaos to conduct military operations against them and the Acehnese civilians. By the end of January, the government declared that it was “forced to kill 120 GAM members.”

“All this is just government propaganda,” says commander Nasir. “After the tsunami we tried to help the Acehnese people. And we did help, before the arrival of the foreign aid workers, because the government did absolutely nothing. About the TNI killing 120 of our fighters – it is absolute nonsense. What happened is this: in Lamno, the army fired at people who came to search for their families after the tsunami, killing 5 civilians and 2 GAM members. We refused to return fire, since we had orders not to fight back.”

I ask him about GAM’s long-term strategy.

“We will fight for the freedom of Aceh and we will never give up, before it is achieved. We want full independence from Indonesia, but we will yield to the wish of our people. If they would opt for something lesser, we will have to accept. But first of all, people have to be consulted: they should have a free referendum. Whatever their decision is, GAM will comply.”

I ask commander Nasir, whether GAM is a religious or secular guerilla force?

“We are definitely not a religious movement, although since this is Aceh, most of us are Muslims. We have no atheists and no Christians among our fighters, but we have many supporters who are Chinese or Christians. If any of them would choose to join us, we would have no problems accepting them. As for the ideology: we are training our fighters in the Acehnese ideology. It means that we give them the Acehnese identity, we teach them our language, our culture and our history.”

Commander Nasir then continues to add, “I would like to thank the international community: Thank you! Thank you for coming here and helping our people. You don’t have to worry about us. We will never harm you. We are grateful. Please stay as long as you can because once you leave, suffering of the Acehnese will increase again.”

TSUNAMI SEEN FROM BANDA ACEH AND JAKARTA

Although both Banda Aceh and Jakarta are in the same country, there is little knowledge in the capital about what really happened during and after the tragedy.

Indonesia is often incorrectly described by the mainstream Western media as a “democratic country.” In reality it is a post-dictatorial society, where big business, military and religious institutions still maintain an unchallenged grip on power and the local media is controlled by the business elites.

“There is a limit to what can be written about the military, for instance,” explains the senior editor of one of the major magazines in Indonesia (he asked not to be identified). “And the same goes for the police. If we cross the line, we are risking our life and our magazine can be ruined.”

“Most of the people get their news from television,” explains an Indonesian TV reporter, who also prefers to remain anonymous. “While magazines can at least offer some criticism, television stations are much more limited. They can’t be openly critical of the government, military and the police. The great majority of the Indonesian public never encounters direct criticism of the government’s handling of the disaster in Aceh. People simply don’t know. And, honestly, they don’t care!”

Dissent is still brutally suppressed. Last year, an influential human rights activist and government critic, Munir, was poisoned on board the Indonesian airlines flight from Jakarta to Amsterdam. No thorough investigation has been conducted yet.

“Government Watch” coordinator and anti-corruption activist, Farid Faqih, was arrested in Aceh in January and still remains in jail, facing ridiculous charges of stealing aid from the military-controlled warehouses. Mr. Faqih was brutally beaten by several members of the armed forces. Vice-President, Jusuf Kalla, described the beating as a “misunderstanding,” while Mr. Faqih still awaits a trial in jail.

At the end of January, an American journalist and filmmaker – William Nessen – was expelled for the second time from the country – this time for entering Indonesia illegally since he is apparently barred from the country. This is ironic given that Mr. Nessen entered the country openly, purchasing his visa upon arrival from the local officials.

This is just a short and an incomplete list of recent abuses against the critics of the system.

While the Acehnese people are outraged by the government’s inefficient response to the disaster, viewers in Jakarta are bombarded by the state sponsored propaganda, describing the glorious deeds of its army and the volunteers. As a result, a majority of Indonesians describe the government’s response to the tsunami as somehow slow, but adequate (according to a poll run by METRO-TV).

There is no public outcry. No heads are rolling. The Indonesian media continues to show tremendous servility and discipline.

TRAUMA AND HOPELESNESS

Those who survived often gather with other victims, sharing their stories, grief and frustration. Some of them lost one or two relatives. Others lost everybody and everything.

Many survivors wander aimlessly through the rubble, others sit on what remains of their homes. There are people who prefer to be surrounded by their relatives and friends (if any survived), others choose to be alone. Most people are quiet; there are hardly any loud and evident displays of despair or sorrow.

“Some people cry, some don’t,” explains Ms. Laetitia de Schoutheete, a famous Belgian psychologist who joined the team of Doctors without Borders in Aceh. “Those people who survived are no longer sure about their future. Right now, they simply can’t afford to cry or to grieve. The moment their security is guaranteed, the grief process will begin. But when it begins, it is very hard to predict what will happen.”

For most of the surviving victims, the “guarantee of security” is still far away. There are almost no jobs in Aceh and the ones available pay meager salaries – too low to save anything in order to start a new life. A full day’s work of cleaning rubble in the city center pays only 30.000Rp – around $3.25. Tens of thousands of small family businesses have been lost, fishing boats destroyed. The government doesn’t seem to have any sound plan for revitalization of the devastated area, although officially it has already moved to the “reconstruction stage.” The United Nations now estimates that some 800,000 people in Aceh will have to be fed for a prolonged period of time – maybe for as long as two years.

Prices for basic food have gone up and so have the rents. Landlords are eager to get rid of some long-term local residents, since they can charge foreign workers a higher rent.

There are alarming reports of forced adoptions. According to Care Aceh, there are 1,130 documented cases of Acehnese children being taken to Medan, capital of Sumatra. “The government has done nothing to stop the trafficking in children. It denies that it is happening and then blocks the investigation. The agency in charge is Aceh Sepakat, backed by the government.” Some links lead to PKS – a religious party with strong links to the government. According to an eyewitness’ testimony, PKS members refused to return a child to a father who recognized (and was immediately recognized by) his own child, demanding legal documents, which in many cases disappeared during the disaster.

Even at the refugee camp run by the PKS party, the situation is desperate. A member of PKS itself, Mr. Hambani – chief of six Syiah Kuala villages – is obviously frustrated: “You know, I don’t even know where their main office is! And I am their member. They gave us almost nothing – some meager load of instant noodles – but when they delivered it, they insisted that we raise their flag over the camp. All they care about is publicity! We got no help from them for 23 days. PKS obviously doesn’t care about us, although 80% of our community voted for them in the last elections.”

INTERNATIONAL HELP

There is no doubt that without the rapid arrival of international help, tens of thousands more Acehnese would have died by now from hunger and disease. As the Indonesian military personnel and police aimlessly hang around the city, military helicopters from dozens of countries are flying to distant and desperate locations of the province, delivering aid, medicine and tents.

Help from the international community is greatly appreciated by the Acehnese people, but makes many officials in Jakarta uneasy. It highlights the inability of the Indonesian authorities to deal with the disaster and allows closer scrutiny of the state and military actions against the civilians and separatists. For a long time, Aceh was off-limits to foreigners. Almost no foreign journalists were allowed in – the official reason being “for their own safety and protection.” Now people who have been suffering for years under the military occupation and economic neglect can voice their grievances.

At the same time, Indonesia is counting on international aid to rebuild Aceh. Billions of dollars will be needed for this gigantic undertaking. The question is, how much will get to the victims and how much will go to pay for the latest models of BMWs and luxury villas of corrupt government officials and their business associates from the private sector?

It is no secret that Indonesia is one the most corrupt nations on earth. Graft is institutionalized and touches every sector of society. Distribution of aid is no exception.

Foreign loans can be counter-productive as well. Indonesian international debt as of December 2004 was $78.25 million (with debt-service ratio of about 30%). The majority of these loans came to Indonesia during the right-wing dictatorship of Suharto. Most of the money never made it to the intended infrastructure, medical facilities and education projects, while the poor and the middle-class (the only ones who are paying taxes anyway) were left with the enormous bill.

Rich countries like the United States and the international financial institutions were well aware of the situation, but continued to suggest new loans. By indebting the nation, they were gaining control over the country and its resources.

Aceh deserves massive foreign aid, but it has to be aid which goes directly to the victims, helping them rebuild their homes and lives, and creating work opportunities. It should not be funneled through the government agencies. Every dollar should be accounted for. If this cannot be achieved, any aid might turn counter-productive.

MILITARY AID AS AID?

After a 13-year break, the U.S. is trying to improve relations with the Indonesian military. Seizing the opportunity that came with the tsunami, it is letting go of its concern about Indonesia’s human rights record that led the U.S. Congress to curb military ties in 1992 and cut off Indonesia’s eligibility for the International Military Education and Training (IMET) Program and to buy certain kinds of lethal military equipment. After the Indonesian army and its militias rampaged through East Timor in September 1999, killing hundreds of people and destroying much of the territory after the East Timorese voted overwhelmingly in favor of independence from Jakarta, the Clinton administration was forced to cut off all ties.

But the Bush administration has long been eager to normalize military ties with Indonesia. All because Indonesia is seen as a potentially crucial player in the war on terrorism, as its army’s main concern appears to be to crush fighters of the Free Aceh Movement.

Since 9/11, the administration has gradually renewed ties by providing aid through new anti-terrorism accounts, resuming joint military exercises, and inviting Indonesian officers to participate in regional military conferences. Condoleezza Rice, the Secretary of State, recently suggested strengthening the American training of Indonesian officers, including training them in modern warfare methods, despite continuing reports of abuses committed by the army in Aceh. In late January, the U.S. supplied Indonesia with $1 million worth of spare parts for its aging fleet of C-130 heavy transport planes, that the U.S. sold to Indonesia over 20 years ago. Some say that it is possible that the the ban on the sale of weapons to Indonesia might be removed soon.

Human rights groups warn that the renewed military aid will be, as in the past, used to suppress independence movements in Papua, Aceh and other hot spots all over the archipelago, and to crush internal opposition and dissent.

The past relationship between the Indonesian government and the United States cannot be ignored. In 1965, the U.S. supported and participated in a military coup which toppled the democratically elected government of Sukarno and imposed the extreme right-wing dictatorship of General Suharto.

Up to 3 million people were slaughtered and Indonesia embarked on the free market experiment which resulted in the social and economic collapse of the fourth most populous nation on earth. While the Clinton administration was forced to break relations with the Indonesian military under immense public pressure, initially the United States and other rich nations (including UK and Australia) supported the occupation of East Timor which led to a genocide in which one third of the population vanished.

The FUTURE OF ACEH

Devastated by the military conflict and tsunami, present-day Aceh may be one of the most desperate places on earth.

One of the greatest fears of the local people is that after the departure of foreign relief agencies and journalists, it will be hermetically sealed again, left to the mercy of the Indonesian military and government officials in Jakarta.

There is an acute need for permanent international presence which could monitor human rights abuses and reconstruction efforts. The land-grab of the coastal areas by the government should be prevented and the local people – victims of the tsunami – should be given the choice whether to rebuild their homes on the present location or to accept relocation.

Human rights agencies should immediately begin a thorough investigation of human rights abuses in the rural areas of the province. There should be decisive support for the referendum on independence. If Jakarta wants to keep Aceh as part of Indonesia, it should offer concessions and perks, instead of keeping the province by force. And at the end, the Acehnese people should be the ones to decide about their future.

Aceh is rich in natural resources. Suharto and his government signed several deals with multi-national companies. For him, these deals brought substantial bribes, but people of Aceh gained almost nothing. If the Acehnese vote for independence, contracts would have to be re-negotiated. This may be one of the main reasons why so far no major foreign power has expressed support for a referendum which would, if held now, almost certainly would lead to full independence for Aceh.

If independent, it is still uncertain what path Aceh would choose.

What is certain is that Aceh is injured. It is bleeding, destroyed, confused and tormented by tremendous losses, by uncertainty, and by fear. It is hard to decide where to start solving the complex web of its problems. But the international community needs to intervene.

This article was originally published by The Oakland Institute.

To comment on this piece: editors@guernicamag.com