By Anna Vodicka

This Friday, the Justices of the U.S. Supreme Court will gather privately to discuss the constitutionality of Proposition 8 and the Defense of Marriage Act. They won’t have law clerks or media crowding the room. They won’t be checking how many Facebook photos have been turned into equal signs. It will be the most significant conversation on same-sex marriage in history, but when it happens they will be, simply, nine people around a table.

If I learned anything from Washington state’s fight for marriage equality last year, it was this: In life and in discourse, beware the trap of the immutable opinion; it’s one thing to hear an argument, it’s another thing to listen.

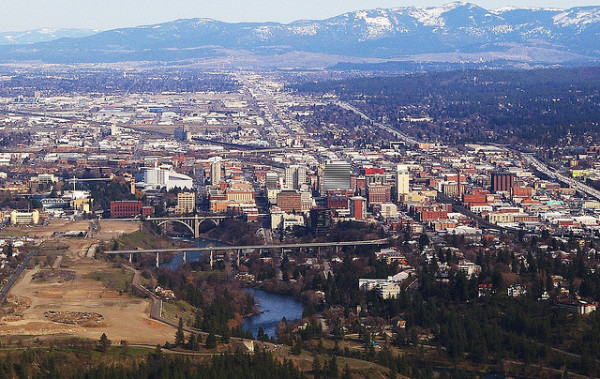

On a Monday night last October, ten fellow volunteers and I gathered in Spokane to phone bank for Referendum 74. A local café stayed open late on our behalf, a courageous act, considering support for same-sex marriage could damage their bottom line. Because unlike Seattle—a veritable Tomorrowland for progressives, a magical world where everything is recyclable, the mayor bikes to work, and liberal dreams come true—east of the Cascade Mountain range, it’s a lot of gun rights and God and custom bumper stickers reading “Romney-Ryan: Don’t Re-Nig in 2012.” This was our phone banking territory. And we would be interrupting dinner.

The call was a simple poll: “Do you support or oppose the right for committed gay and lesbian couples to marry in Washington?” If folks opposed, we would bid them thanks and goodnight. If they supported, we would remind them to vote to approve in November.

If they were undecided, we would talk.

Pretty straightforward, I figured. I come from a conservative family in a God-fearing, Midwestern town—I know the arguments. I had been door-to-door canvassing, and had even been a missionary once, in a past life; I’d have no problem calling on strangers.

The 2012 election was a month away. No state had yet approved marriage equality by public vote. To me, Referendum 74 represented a tipping point in the defining civil rights movement of my time, and I was too nervous to sit by and watch the scales hover.

Planting ourselves in café booths, we opened our laptops, watched a software program generate numbers, and clicked CALL.

“Hello. My name is Anna. I’m a volunteer with Washington United for Marriage. We’re calling to ask if you support or oppose…”

“Strongly oppose.”

“Oppose.”

“Being gay is wrong. It’s a choice and I won’t support it.”

“Homosexuality is disgusting!”

“I believe marriage is between a man and a woman, as ordained by God, and everything else is a perversion.”

I listened to hundreds of voices over the line that night, an explosion of feeling, words thrown like stones.

After an hour—had it really only been an hour?—I contemplated inventing a reason to leave. My head hurt. My heart felt lodged in my throat. I scanned the room for signs from the others that we should call it quits. Their faces mirrored mine, but they kept going.

“I believe what the Bible says. I believe in the teachings of Jesus. I will never support that.”

“Homosexuality is an abomination.”

“You people don’t deserve to be alive.”

Maybe I’d caught them on a bad night. Maybe people who engage with strangers over the telephone have a tendency toward radicalism, vitriol, or loneliness. Maybe the anonymity of the phone call emboldens folks to speak thoughts they might otherwise filter. Or maybe fear of the Other is pervasive, more than I realized—a wall built by polarized politics and personalized news feeds wrapping us in cocoons of comfortable information. Maybe these conversations were wretched because they were rare; having tuned out people on the other side, we’ve forgotten how to talk to each other across the divide.

I listened to hundreds of voices over the line that night, an explosion of feeling, words thrown like stones.

At 9:30 p.m., I walked to my car and sat in the driver’s seat, frozen by the reminder that even if this historic vote passed, the harder fight—against fear and discrimination—was still, as ever, ahead.

I was surprised to find my greatest sources of hope in a high school freshman, a hip-hop artist, and a retired woman I will never meet named Denise.

On October 9, Seattle-based indie rapper Macklemore released his debut studio album, The Heist, with producer Ryan Lewis. The album immediately topped iTunes and Billboard charts. The track “Same Love,” a pro-marriage-equality anthem, racked YouTube hits in the millions.

I don’t typically get music recommendations from ninth graders, but my boyfriend’s young cousins were crazy about this album. For fourteen-year-old Kellen and his classmates, Macklemore is the subject of endless Facebook, Twitter and hallway chatter. When The Heist tour hit Spokane, they packed the house, singing along to “Same Love” with next-generation ingenuousness.

When I was in high school—just ten years ago—“fag” was everyday hallway vocabulary.

Now, a generation of teen boys is crooning a hook sung from a lesbian perspective (Mary Lambert sings the refrain, “I can’t change/even if I tried/even if I wanted to…”). I’m imagining my male high school peers belting, “I’m coming out!” and “It’s raining men!”—and no one threatening to beat the shit out of them for it. Hallelujah.

Bernice Johnson Reagon, one of the original Freedom Singers—the gospel group who put the Civil Rights movement to music—once said the group’s songs were “more powerful than conversation. They became a major way of making people who were not on the scene feel the intensity of what was happening in the South.” To hear “Same Love” is to experience that power.

It’s reminiscent of another Civil Rights anthem: Curtis Mayfield’s “People Get Ready,” released to instant pop acclaim one year after the March on Washington. “There’s a train a’comin,” Mayfield sang. “Don’t need no baggage/just get on board.” That train signaled a meaningful move in the direction of equality, liberty and justice. You know—for all.

Macklemore may not redefine hip-hop the way Mayfield redefined gospel, but he is challenging his genre to transcend sexual stereotypes and radically rethink language in lyrics (“If I was gay, I’d think hip-hop hates me/Have you read the YouTube comments lately?/‘Man that’s gay’/Gets dropped on the daily”). And while, as of this writing, Macklemore’s “Same Love” has roughly 28 million YouTube hits to his “Thrift Shop” song’s 193 million, the track recently hit the Billboard chart’s top 100. If global success is any indicator, it’s only moving up.

Music can be a driver for fast-tracking social change, making way for other types of dialogue and, eventually, for social progress. It takes a united front of pop culture, public and political agendas to achieve a collective consciousness-raising. And it takes the sometimes harder work of regular people gathering around tables, talking. Holidays. School nights. Supreme Court conferences.

But human beings are built for movement. Sometimes, votes swing.

The Justice’s conference is a significant event. Chief Justice Roberts will run the meeting, and by the end of the day the Court alone will know its inaugural vote. The most senior Justice in the majority will assign the opinion—though the authorial role can shift over the following weeks and months, as the Justices negotiate, debate, and vie for majority rule.

Last week, the Pew Research Center released a poll showing a radical tectonic shift in favor of public support for marriage equality over the last decade. The explanation? Young people pushing progress right past their own fixed-opinion parents, and the catalytic combination of open minds and dialogue. “When those who say they have shifted to supporting same-sex marriage are asked why their views changed,” the study reports, “…[r]oughly a third (32 percent) say it is because they know someone—a friend, family member or other acquaintance—who is homosexual.” Twenty-five percent said their view changed because they had “grown more open” or “thought about it more.”

The study also reminds us that some people live permanently with hands clapped over their ears. By comparison to the 28 percent of marriage equality proponents who say their views have evolved, “virtually everyone who opposes same-sex marriage—41 percent out of 44 percent—say they have always been against it.”

Surely, some of the people I spoke with while phone banking fell into this category. The wall was up. The vote already cast. They wouldn’t listen; they could barely even hear me.

But human beings are built for movement. Sometimes, a song works its way into the streets and the melody is too beautiful not to sway and hum along. Sometimes, votes swing.

In my dimly lit booth at the coffee shop, I checked my phone for the time: 8:40 p.m. The café owner collected plates and tea mugs. I took a deep breath and clicked CALL beneath a name on the screen: Denise in Colville, a logging town in one of the state’s most conservative counties.

“Hello?” A woman answered. It was Denise. I said I hoped I wasn’t interrupting her evening and explained the reason for my call.

She hesitated. Finally, she said, “I’m a Christian. In the end I have to side with the Bible, so I’m going to vote no.”

She spoke kindly, with no edges in her voice or in her simple conviction of faith, and waited for my response. Guessing by her voice, she was about my mother’s age, late fifties or sixties. I pictured her standing alone in a kitchen—imagined her talking into an improbably rotary phone—preparing a quiet meal, a cat curling its body around her ankles. All at once, I was reminded of the fact that the telephone, which blinds us, leaves everything but sound to the imagination. Her assumptions would be based on my words and my voice, not my hair or my handshake. We were two people connected by an invisible line. Already, we had things in common.

I’ve been agnostic since high school, when on a mission trip I discovered the people I was taught to convert already exhibited the selfless attitudes of Christ, which was more than I could say for myself and my Youth Group peers. Unlike some of my fellow unbelievers who find it easy to shrug off religion as anti-intellectualism or cult mentality, and who sometimes fall prey to their own fixed ideas (“evangelical atheists,” I tease friends sometimes), I could understand where Denise was coming from. I took a deep breath and attempted common ground.

“I was raised Christian, too,” I said. “To me, the Bible’s most important messages are the Golden Rule and God’s commandment to love one another.”

The phone went silent. I was pretty sure Denise had hung up her old-timey phone and gone back to her supper.

“I never thought of this issue in that way,” she said.

We talked for thirty minutes, kept talking as my fellow volunteers closed laptops and collected belongings.

“You know,” she said, “when I was in my twenties, I lived in Seattle and I knew a guy who was…like that…he didn’t say he was, but everyone knew and I liked him. He was funny. He was just like anyone else, just a regular person.”

It is a scary, unbalancing thing to experience the extraordinary sensation of shifting.

I thought of the statistics, that people change their mind about the Other once they have a personal experience and the Other becomes another person. I encouraged her to tell me more. I asked about her family and friends. She told me her husband wasn’t well. She was going through a tough time.

“I’m so sorry,” I said, and I felt it. I told her about a friend of mine with cancer who was being denied partner benefits because she was gay and couldn’t marry in her state of residence.

“That would be very hard,” she said, her voice low. “I’m sorry for your friend.”

When it was time to hang up, I thanked Denise for the most rational conversation of the evening. I told her that everyone else I’d spoken with had either hung up on me or might as well have.

“To be honest,” she said, “I wasn’t going to talk to you at first. I don’t normally do this sort of thing. But you sounded…nice. I’m not used to people on the other side actually listening to me.”

“Me neither,” I laughed.

Denise’s pastor had instructed her congregation to vote “No” on the Referendum. Now, she said, she wasn’t sure. She had some things to think about.

“You’ve given me things to think about, too,” I said.

Months later, I’m still thinking about Denise. I wonder how her husband is doing. I think about the challenge she faced in parsing her own convictions from her church’s. And I think about her reasons for staying on the line, the emphasis in her voice when she said listening.

I used to teach rhetoric—the dance of argument, a civic art often reduced to a squabble—to university students, whose natural tendency was to see partners in the dance as opponents. It was easy for them to exercise free speech, much harder for them to listen to anyone else’s.

Listening is a choice, a difficult craft we can all practice, even amid the constant distraction and noise, even if only to one person: a child, a street musician, a stranger on the phone, or a colleague and friend across the table. It’s about Scalia taking Ginsburg’s argument seriously when she compares federally unrecognized state marriages to “skim milk.” But it’s also about Kagan and Sotomayor processing Alito’s assertion that same-sex marriage is younger than our cell phones. It has to go both ways. Otherwise, we miss it—the sound of a great, turning world, with magical storms and roaring oceans and a bedrock foundation beneath our feet that is always, always shifting.

Predictably, only one county east of Washington’s Cascade Range voted in favor of Referendum 74 (this county happens to include Washington State University, i.e. 20,000 young voters). But it was enough, and by now we know the scales tipped: Maine, Maryland and Washington voted for equality.

In other words, we’re picking up passengers from coast to coast, and even Minnesota, which refused to ban same-sex marriage, won’t pass up a seat on the train. Oh, and another thing: “There ain’t no room for the hopeless sinner/Who would hurt all mankind just to save his own/Have pity on those whose chances grow thinner/For there’s no hiding place against the Kingdom’s throne.”

Let’s do have pity for those who fear, and whose fear breeds hate. Send them love, as much as you can spare. It is a hard but essential thing to critically think about our beliefs, to hear other perspectives, and patiently challenge ourselves to listen—a scary, unbalancing thing to experience the extraordinary sensation of shifting.

When I was a kid, my family gathered nightly around the table to give thanks. On March 29th, as nine Justices gather around America’s table, I will offer up this bit of grace: Thank you, Macklemore, for capturing the spirit of the march. Thank you, Kellen and the youth vote, for giving me hope for a better Tomorrowland. And thank you, Denise in Colville, or wherever you are, for having a conversation.

Anna Vodicka’s essays have recently appeared in Brevity, The Iowa Review, Michigan Quarterly Review, Ninth Letter and Shenandoah. She holds an MFA from the University of Idaho and currently writes from Spokane, where she is practicing (and failing, and failing better) at the art of listening, yoga, the guitar, and a memoir-in-fragments about rural America, faith and family. You can find more of her work at www.annavodicka.com.