By Nikole Hannah-Jones

By arrangement with ProPublica

For the past four decades, federal officials and civil rights lawyers have wielded a potent legal weapon in the fight against housing discrimination. Even when they couldn’t prove that practices of landlords, lenders or governments were racially motivated, they could win cases by showing minorities had suffered disproportionate harm.

The Obama administration has used the principle of “disparate impact” to reach record settlements with banks accused of discriminatory lending and to confront localities whose housing policies limited opportunities for black and Latino renters. A senior official recently said that the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development is pursuing more than two dozen cases based on the theory.

Those cases, and others brought by civil rights groups and other agencies, could soon be halted in their tracks. For the second time in two years, the Supreme Court is poised to review a case that challenges whether the concept of “disparate impact” can be used to enforce the 1968 Fair Housing Act.

Officials from the U.S. Department of Justice and HUD, the agency charged with enforcing the housing law, have repeatedly declined ProPublica’s interview requests. But Sara Pratt, HUD’s chief of enforcement, bluntly told attendees at a recent conference on housing issues that the disparate impact standard is essential for deterring housing bias because the days of “pants-down discrimination” have ended.

“Landlords, housing professionals, zoning and planning boards, have learned to stop talking about it,” Pratt declared. “What they haven’t learned is to stop doing it.”

Over the past year, Obama administration officials have become increasingly concerned that the high court is preparing to strike down the use of the disparate impact standard in housing cases. In an attempt to dissuade the justices from intervening, the Obama administration is preparing to release a long-stalled federal rule this month that enshrines “disparate impact” in the regulations for enforcing the federal housing law.

The move comes as the Supreme Court, led by its conservative majority, appears set to curtail affirmative action and the Voting Rights Act, two other tent poles of the civil rights movement.

If the court strikes down disparate impact, it would largely limit civil rights lawsuits against landlords, homeowners, or governments to those rare cases in which it could be proven that governments or businesses had an explicit intent to discriminate.

Disparate Impact, A Lynchpin of Enforcement

The principle of disparate impact is not directly mentioned in the landmark Fair Housing Act but has been accepted over a period of forty years by a series of federal judges who have ruled on housing cases.

Housing advocates have been urging HUD to adopt the regulation for years. Because the Supreme Court has long deferred to an agency’s regulations when interpreting the law, Alan Jenkins, executive director of the nonprofit The Opportunity Agenda in New York City, said it “could be the deciding factor, not only in what disparate impact means, but whether it exists after going before the Supreme Court.”

In 2011, federal officials persuaded the city of St. Paul, Minn., to withdraw a case accepted for review by the Supreme Court that questioned whether the principle could be applied in housing cases. “We were afraid we might lose disparate impact in the Supreme Court because there wasn’t a regulation,” said Pratt, who also led fair housing enforcement during the Clinton administration.

If the court strikes down disparate impact, it would largely limit civil rights lawsuits against landlords, homeowners, or governments to those rare cases in which it could be proven that governments or businesses had an explicit intent to discriminate.

“If the court overturns disparate impact,” said Florence Roisman, a fair housing scholar at the Indiana University School of Law. “It is going to gut the statute.”

In one such case, the Justice Department found that Countrywide—a now-defunct mortgage company purchased by Bank of America—charged black and Latino borrowers higher rates and fees than white applicants with similar credit histories.

Release of the regulation sometime this month will set a tone for President Obama’s second term and several scholars said it would be among the most important civil rights regulations to come out of HUD in at least a decade. But its release may be too late to influence the high court’s ruling.

Key Battles in Countrywide, Katrina Cases

Even without the regulation, the Obama administration has aggressively pursued disparate impact cases.

Under President Obama, the Justice Department created a unit to focus on discriminatory behavior in the banking industry and has used disparate impact to win massive settlements.

In one such case, the Justice Department found that Countrywide—a now-defunct mortgage company purchased by Bank of America—charged black and Latino borrowers higher rates and fees than white applicants with similar credit histories. It also discovered that black and Latino borrowers who qualified for prime loans were more than twice as likely to be steered to subprime loans as similar white borrowers.

Countrywide issued no official policy telling loan officers to discriminate. But it did give them discretion to steer well-qualified buyers into less favorable loans. In what Assistant Attorney General Thomas Perez called “discrimination with a smile,” that authority was used largely on loan applications from African Americans and Latinos. Bank of America could not produce a legitimate business practice to explain the discriminatory results, a defense against an action brought under the disparate impact standard. The bank settled with the Justice Department for $335 million in 2011—a record in a residential lending case. It did not acknowledge wrongdoing.

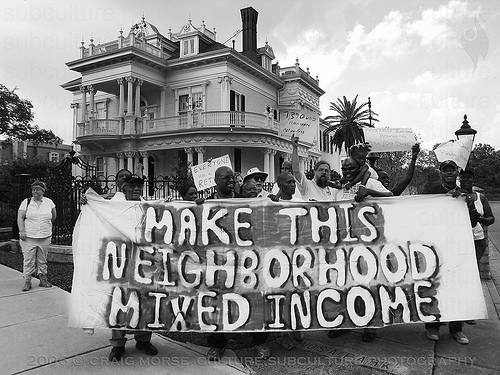

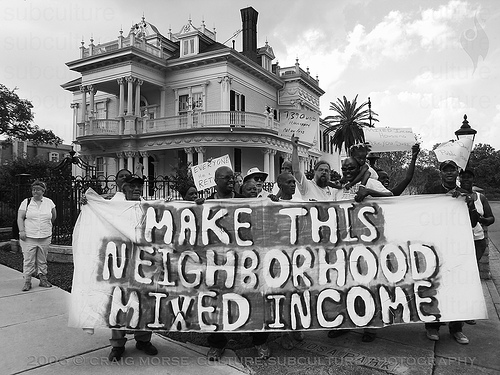

As residents of largely black New Orleans sought to find housing in St. Bernard’s, a predominantly white enclave just across the border, the parish passed a law that prohibited homeowners from renting to anyone who was not a “blood relative” unless they received a permit from local authorities.

In another major case, a private fair housing group and later the federal government used the disparate impact standard to challenge policies adopted by St. Bernard’s Parish, La., after Hurricane Katrina.

As residents of largely black New Orleans sought to find housing in St. Bernard’s, a predominantly white enclave just across the border, the parish passed a law that prohibited homeowners from renting to anyone who was not a “blood relative” unless they received a permit from local authorities.

Since 93 percent of the homeowners in the parish were white, the government argued that the laws aimed at restricting rental housing would have disproportionately prevented people of color from moving in.

“Do you think St. Bernard’s parish was really trying to keep black people out?” Pratt asked at the housing issues conference. As heads began to nod, she asked, “Does anyone have any evidence?”

The administration, which has seen the fight over disparate impact building for several years, promised early in Obama’s first term that it would issue a regulation.

Advocates cheered. Then they waited. And waited.

Mondale Warns Against Supreme Court Decision

By 2011, a case that had been winding its way through the lower courts landed at the Supreme Court.

A group of landlords had sued St. Paul claiming that its stepped up property code enforcement violated the Fair Housing Act because it reduced the availability of low-income rental units and had a disparate impact on black residents.

Since the landlords were essentially arguing that the anti-discrimination laws gave them a right to not maintain apartments in black areas, the city of St. Paul fought the suit.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit ruled the landlords had made a valid disparate impact claim, prompting St. Paul to appeal, arguing that the Fair Housing Act required proof of discriminatory intent and not simply discriminatory results.

A week after the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case in November 2011, HUD finally released a proposed regulation, which set a single standard for proving violations of the Fair Housing Act. The proposed rule codifies within federal regulations the ban on practices that have discriminatory effects unless they can be shown to serve a legitimate purpose for business or government.

Although all eleven appellate courts that have ruled on the issue have held that the Fair Housing Act allows disparate impact claims, the Justice Department and housing advocates feared the conservative majority on the Supreme Court would not agree.

Minnesota native son former Vice President Walter Mondale, who helped write the 1968 law, urged St. Paul’s mayor to withdraw the case. According to news accounts, Mondale called disparate impact the only means of effectively enforcing laws against housing discrimination and asked the city not to risk a “Supreme Court decision that ruins the act.”

The Justice Department agreed not to intervene in two unrelated lawsuits against the city, a move now under investigation by congressional Republicans who say the administration offered the concession to persuade St. Paul to drop the disparate impact suit.

St. Paul acquiesced, and in February 2012 the parties took the rare step of withdrawing the case from the Supreme Court’s docket.

At issue is the town’s efforts to redevelop a predominantly black area it considered blighted. The town bought and destroyed most of the homes in the neighborhood but has not built the new housing. Former and current residents sued, saying the town’s actions had a disparate impact on African Americans.

The Fight From Big Business

Meanwhile, lobbyists for the influential banking, lending, and insurance industries launched a broad campaign against the draft rule.

Robert Detlefsen, vice president of public policy for the National Association of Mutual Insurance Companies, said his organization, which represents home insurers, opposes the regulation because it would place an unfair burden on companies to prove that policies that harm one group more than another are not discriminatory.

Businesses should not be penalized “because of a statistical disparity,” Detlefsen said. “As long as it could be shown that there was no intent to discriminate racially or ethnically, there should be no controversy.”

The American Bankers Association, the National Multi Housing Council and the Mortgage Bankers Association either declined or did not respond to interview requests from ProPublica.

The business community’s pushback seemed to work.

“The proposal was on the table last year at this time. As you got into July and August, the White House just let it be known that ‘We just can’t do it in this political season,’” said Robert Schwemm, a constitutional law and civil rights scholar at the University of Kentucky Law School. “Just to rattle off the groups that have decided to oppose it is to list some of the most powerful groups in Washington, even with a Democratic administration.

“The Obama administration delayed, delayed, delayed.”

Pratt acknowledged as much during her presentation. “The industry doesn’t like it. They are scared of it,” she said. “Disparate impact is incredibly controversial politically. It is not controversial legally.”

With Obama fighting his final re-election battles in October, the Supreme Court signaled that it might take up the issue again. The Court asked the U.S. Solicitor General to submit the government’s stance on disparate impact in a case involving the New Jersey township of Mount Holly. It has not yet decided to hear the case.

An Eleventh-Hour Effort

At issue is the town’s efforts to redevelop a predominantly black area it considered blighted. The town bought and destroyed most of the homes in the neighborhood but has not built the new housing. Former and current residents sued, saying the town’s actions had a disparate impact on African Americans.

Most scholars interviewed for this story believe that Justices John Roberts, Clarence Thomas, and Samuel Alito would strike down disparate impact, but are less sure about the stances of Justices Antonin Scalia and Anthony Kennedy.

After a court ruled the plaintiffs had a valid disparate impact claim, Mount Holly appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing as St. Paul had that Congress did not write disparate impact into the fair housing statute and therefore did not intend to allow it to be used as a legal standard.

Mount Holly’s appeal did not shake the regulation loose—to the dismay of some observers. “It is enormously important that HUD promulgate this statute,” said Roisman. “Frankly, I think it is unconscionable that HUD hasn’t done it in the last four years—they should have done it long before that.” Most scholars interviewed for this story believe that Justices John Roberts, Clarence Thomas, and Samuel Alito would strike down disparate impact, but are less sure about the stances of Justices Antonin Scalia and Anthony Kennedy. One of them would have to join the Court’s liberal block if disparate impact were to survive.

Scalia indicated in a previous case involving employment that he was open to an argument that disparate impact in any arena violated the equal protection clause of the Constitution. However, Scalia, who was an administrative law scholar before becoming a constitutional law scholar, has also said he believes in deference to agency regulations.

But several legal scholars pointed out that the Court’s track record under Chief Justice Roberts provides little certainty that it will follow that precedent.

john a. powell, a civil rights scholar at the University of California, Berkeley Law School, said the Supreme Court would not normally take a case such as this one where the lower courts are unanimous in their interpretation of the law. But powell, who spells his name without capital letters, said this court has shown an eagerness to dismantle civil rights protections even when case law is well established—one reason for concern that HUD’s new regulations may not stand.

“If [the Supreme Court] is going to ignore the circuits and decades of precedents from the federal courts, I don’t know that it is going to be turned around by the regulation of an agency,” powell said. “It is not waiting on controversy in the lower courts, which is the normal case. If it strikes down disparate impact that would be a huge change, but the Court is rewriting issues around civil rights and race.”

The administration’s 11th-hour release of the regulation may have served mostly to rally the opposition. Detlefsen said his group did not file briefs opposing disparate impact in the St. Paul case, but likely will if the Court takes up the Mount Holly case. “The regulation has gotten the attention of a lot of people in the insurance industry,” he said. “Absolutely.”

Civil rights advocates are watching, too.

“The search for racists is for the most part a fool’s errand. There is no way in a court of law to prove or know what is in someone’s hearts or minds,” Damon Hewitt, an attorney at the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, said at the housing conference. “The preoccupation with disregarding racially disparate impact means people are willing to accept racial disparities and then say there is nothing the law should do about it.”

UPDATE: The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development issued the final rule (PDF) on disparate impact under the Fair Housing Act on February 8. In doing so, the agency formalized for the first time a national standard for establishing when housing practices that disproportionately harm racial minorities, the disabled, and other protected groups violate civil rights law.

Nikole Hannah-Jones joined ProPublica in late 2011. Prior to that, she covered governmental issues, the census, and race and ethnicity at the Oregonian. There she exposed significant shortcomings in the enforcement of fair housing laws in Portland, and eventually prompted officials to draft the city’s first fair housing plan. She has won the Society of Professional Journalists Pacific Northwest Excellence in Journalism Award three times.

Before the Oregonian, Hannah-Jones was a reporter at the News & Observer in Raleigh, N.C., where she covered school equity and the racial achievement gap. She has also gone on reporting fellowships to Cuba and Barbados where she wrote about race and education.