By Lewis West

“Century of the Common Man,” a series of nineteen silkscreens currently on view as part of the Mary Ryan Gallery’s exhibit Hugo Gellert: Free Radical, embodies the optimism of a pre-war radicalism long since absent from American politics. The piece illustrates select passages from a speech delivered by Vice President Henry Wallace—though the transcript does not accompany the display, we can easily imagine the immediacy and fire with which Wallace must have at least attempted to deliver the speech. Hugo Gellert (1892-1985), a Hungarian immigrant to the US known primarily for his murals and illustrations, used a simple and unyielding mix of bright blue, red, and yellow to mirror the power and peril of his time. Made in 1943, the silkscreens’ colors and compositions suggest urgency even before we examine their content.

Committed to activism through art, Gellert worked for various leftist magazines like The New Masses and The Liberator before joining the staff of The New Yorker and later The New York Times. We can read his work in two ways. On the surface, “Century of the Common Man” is a textbook product of early 20th century radicalism. The first panel shows two farmers holding bunches of grain above their heads. Their bodies are thick, muscular, and colored with vibrant reds. Their expressions refuse ideal visions of placid farmland and demand instead a future of cooperation and broad “progress.”

His figures dive through waters cut by exaggerated waves and ripples… They embody the potential of man unchained.

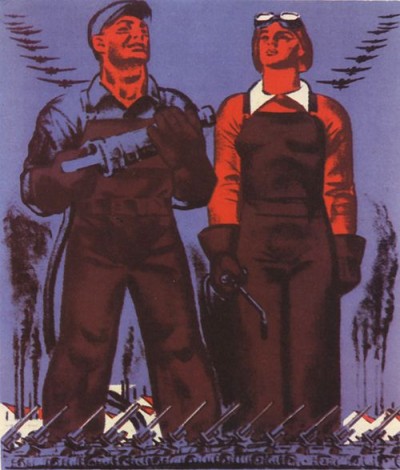

The apparent message of the next silkscreen is again a call for a political producing class. In it, fleeing Nazis look over their shoulders to see not soldiers, but the tools of industry following close behind. Not militarism but proletarian industrialism will defeat the Reich, and with it, tyranny and inequality. Watching from a panel on the edge of the series is a calm and steadfast Roosevelt. Below him, Gellert again depicts the transcendence of color and creed: the Cross, Star and Crescent, and Star of David sit packed tightly together. In front of the three symbols is a piece of paper where the words “Buddha” and “Confucius” are written in capital letters. Not quite equal representation, but close enough.

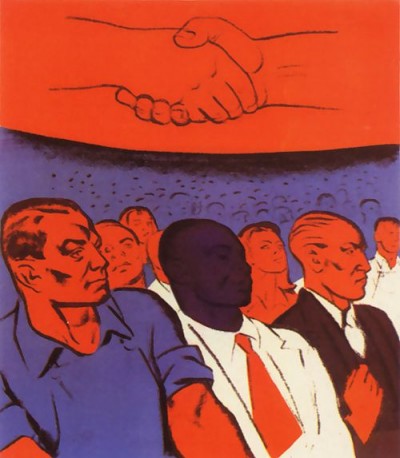

The progressive industrialism of “Century of the Common Man” is present in Gellert’s political posters on display as well. Again, rough-hewn laborers march against factory skylines calling for an end to socioeconomic injustice. If we weren’t careful, we could mistake this for post-communist kitsch. To persist in reading Gellert’s work as beholden only to industrial radicalism, however, ignores the true strength of the exhibition. In arranging Gellert’s silk-screens and posters next to his paintings—the latter from the 1920s and the focus of the exhibition—the gallery forces an interpretation of Gellert’s work that goes beyond established political ideologies, and creates meanings more complex than the party line.

In these paintings, industry and progress recede into the background. They are still there, but dominated by a different subject. Gellert places the individual—usually colored in bright orange and red—at the center of his compositions. His figures dive through waters cut by exaggerated waves and ripples. The heavy black lines reflect the motion and energy of the swimmers. The works embody the potential of man unchained.

Gellert avoids falling prey to the mythology of industrial progress, though he uses its vocabulary.

Another painting—they are all untitled—shows a man, frustrated, tired, and dressed as if just off work. Beside him, factory chimneys pour gray smoke into a red sky. The man seems to compete with the factory; they jostle for space within the small frame. Rather than unbridled confidence in the power of the machine, the piece evokes the tension latent in any tight juxtaposition of industry and worker. To Gellert, the emotion of the man takes clear precedence.

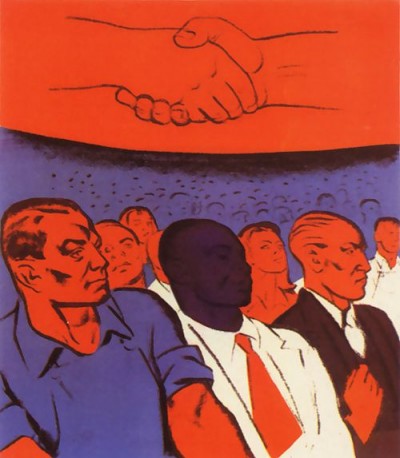

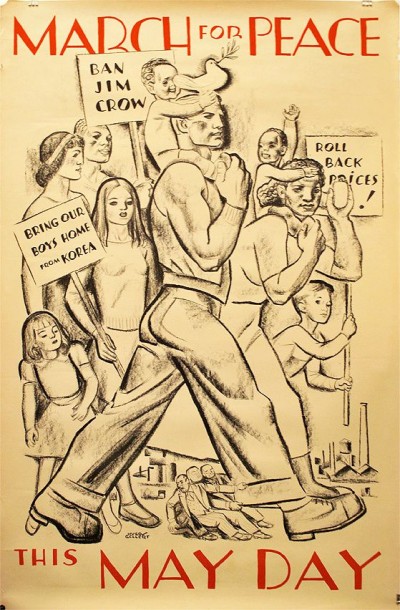

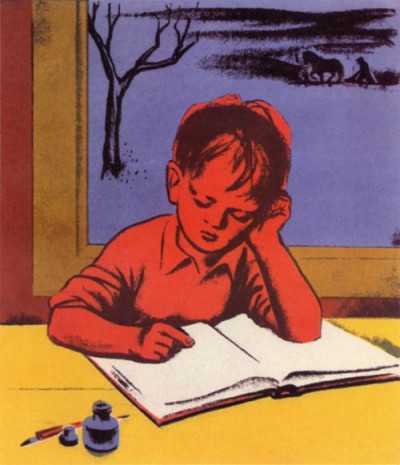

This attention to the individual body, to the centrality of the human, underscores all of Gellert’s work. Without his paintings, this is easy to miss. In “Century of the Common Man,” the emaciated specter of Nazism, blood dripping from its fingertips, easily overwhelms more everyday scenes. Yet it is the workers’ meeting, the student (somewhat dejectedly) copying his homework, that comprise the core of Gellert’s art. In his poster “Ban Jim Crow,” protesters gather in front of a city of factories and smokestacks. The city, though central, is dwarfed by the men, women, and children demanding an end to institutionalized racism. They are the primary agents of Gellert’s politics.

One can at any point reduce this radicalism to a dogmatic concern for the “worker.” But Gellert avoids falling prey to the mythology of industrial progress, though he uses its vocabulary. He speaks the language of class conflict while recognizing that such identification does not and cannot encompass the entire lives of his subjects. He likewise rejects harshly reductive views of “the masses,” breaking from elites of all parties who, despite their utopian fervor, see the disenfranchised as little more than a mob. Instead, he paints a history governed not by economics, technology, or elites, but by the power of the individual firmly committed to a just and cooperative future.

Hugo Gellert: Free Radical runs until January 12th at the Mary Ryan Gallery in New York.

Lewis West is an intern at Guernica Daily and a student at Columbia University.