I am sharing a turkey sandwich from the Alcatraz landing cafe with my mother—who is here on vacation and the sole motivation for this outing. I hear the woman behind us on the ferry say, “I’d really just rather not eat than eat something not good, you know? I eat whatever I want as long as it’s good.” It costs twenty-eight dollars to tour a prison that was in active use within the last fifty years. On Alcatraz Cruises’ fuel-efficient, low-emission ferry, it’s steamy on the upper passenger deck, which is enclosed in glass. The breathy heat inside combined with the mist and fog over the water makes it difficult to make out much of anything through the windows.

We’ve been out on the water for maybe ten minutes when out of the mist erupts a huge, white, square sign with hand-painted black lettering: WARNING: PERSONS PROCURING OR CONCEALING THE ESCAPE OF PRISONERS ARE SUBJECT TO PROSECUTION AND IMPRISONMENT. It’s mounted on the southeastern end of the steep and rocky island, above fencing, shrubbery, and an abrupt drop into churning water.

One in forty-three adults in this country is behind bars or on probation or parole.

The hum of small talk lulls, then increases sharply in volume and pitch as more and more people notice the sign, which we’re pulling closer to by the moment. Passengers start poking each other, pointing, saying things like “Oh my god!” and “So creepy!” A non-negligible number whip out their smartphones with the speed of Old-West pistol duelists and begin snapping photos. Artificial shutter sounds crack again and again.

And here is where I begin to feel conflicted.

At the end of 2010, 7.1 million adults were under supervision of the U.S. correctional system; 2,266,800 were incarcerated. One in forty-three adults in this country is behind bars or on probation or parole. Seemingly a book a month is published on the American criminal justice system and its flaws; recent notables include William J. Stuntz’s The Collapse of American Criminal Justice, which attributes the problems of the system to racial discrimination, increased power in the hands of individual law enforcement agents, and backlash against the leniency of earlier courts, and Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow, which argues that the criminal justice system, in its systematic racial discrimination, replicates the apartheid of the old American South.

California’s state correctional system is the country’s whipping boy, and for good reason; the system is overcrowded—it’s not uncommon to see cells with triple bunks and prison gymnasiums filled with bunk beds—and fails to provide basic services and protections to inmates: prison rape is pandemic; the health effects of the crowding are so widespread that an application to serve as a librarian in San Quentin’s Prison University Project requires multiple acknowledgements that you, the applicant, will be exposed to tuberculosis and agree to a regimen of testing. In 2011, the Supreme Court ruled that prison conditions in California constituted cruel and unusual punishment and mandated that authorities reduce the prison population by more than thirty thousand inmates. The federal system, while not as plagued with overpopulation, has its own problems—among them, an uncheerful tendency to lock offenders away in solitary confinement for years at a time.

Alcatraz Island, understandably, does not bill itself as a place to spend twenty-eight dollars to get really depressed about a country’s piss-poor priorities regarding human rights.

The problems with the U.S. correctional system don’t end with the sheer number of lives it touches. There is also the matter of the types of lives it touches: according to the Prison Policy Initiative, inmates per 100,000 blacks, Latinos, and whites number respectively 2,207, 966, and 308. The issues don’t stop with U.S. citizens; increasingly, convicted undocumented immigrants are incarcerated in institutions managed by for-profit prison corporations, where there can be little operational oversight. At the beginning of 2012, the largest of these corporations, the Corrections Corporation of America, sent letters to forty-eight states offering to purchase their cash-strapped correctional facilities. Taking the CCA up on such an offer might mean savings for the states and counties in question; what it would mean for prisoners is less clear. A National Magazine Award-winning feature by Tom Barry, Senior Policy Analyst at the Center for International Policy, documents the death of Jesús Manuel Galindo, an inmate at a corporation-managed prison in Texas who died in solitary confinement following an epileptic seizure. His health records were apparently ignored by prison officials.

The crucible of the current economic climate has affected our correctional system as well. Budget strain has led high-prison-population states like California and Texas to cut their reeducation and job-training programs, and employer screening processes that have become all but standard often keep job applicants with criminal records from reentering society as productive members of the workforce. Some cities and states have pushed back against this practice—Detroit, for example, held an ex-cons-only job fair last fall—but the paltry level of sympathy voters, and by extension policymakers, have for ex-offenders makes this kind of discrimination largely uncontested. Felons, of course, cannot vote themselves. In many states, ex-felons are permanently disenfranchised. As Robert Perkinson notes in Texas Tough: The Rise of the American Prison Empire, our correctional system “no longer aim[s] to repair and redeem but to warehouse, avenge, and permanently differentiate convicted criminals from law-abiding citizens.”

Whatever the original goal of extended incarceration was, it has largely and indisputably failed. Violent crime has not been eradicated in this country; it’s at more or less the same level that it was in the 1960s, though the incarceration rate has jumped by 50 percent. The last official broad study of recidivism by the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics was conducted in 1994; it shows that upwards of 60 percent of paroled offenders were rearrested within three years. More recent reports by independent organizations like the Pew Center for the States suggest these numbers are holding steady. By any measure, prisons are failing to deter, punish, or rehabilitate.

Alcatraz Island, understandably, does not bill itself as a place to spend twenty-eight dollars to get really depressed about a country’s piss-poor priorities regarding human rights. Instead, the National Park Service’s stance is a curiously muted mix of conservation and historicism. “The history of Alcatraz is surprising to those that only know the Hollywood version,” declares the NPS website. “Civil War fortress, infamous federal prison, bird sanctuary, first lighthouse on the West Coast, and the birthplace of the American Indian Red Power movement are a few of the stories of the Rock.”

It’s easy to comprehend the urge NPS must feel to prime visitors to encounter a multifaceted, pleasantly enlightening Alcatraz. And yet, that “infamous.” It’s as if even our best-trained men and women, the people whose entire job it is to interpret Alcatraz and present it to the world, take for granted that “incarceration” = “infamy.” Every alternative narrative the NPS presents to that of Al Capone and George “Machine Gun” Kelly is somehow resisting this powerful underlying assumption. There’s no confidence that the average visitor will have any interest in these alternative topics. Perhaps worst of all, there’s no indication that a visit to Alcatraz will stimulate consideration of the history of imprisonment in the United States—a history that Alcatraz has played a central part in shaping.

Five minutes after our initial Alcatraz sighting, we, the thrill seekers, are disembarking the ferry in the fog and being informed of a climb to the cellhouse at the top of the island, the equivalent of a thirteen-story change in elevation. Mobility assistance, restrooms, and braille guidebooks are available. Food, however, is not available beyond the dock. An amplified voice announcing the island’s amenities is coming out of the fog near the bookstore at the dock, and a few visitors are pausing to congregate around the speaker, who is standing on a set of wooden stairs as if anticipating a great scrum of listeners. Instead of circling her, we are all moving up the hill, undeterred by the mild threat of thirteen stories, eager to get at our “award-winning audio tours,” the existence of which the loud-speakered voice is now informing us.

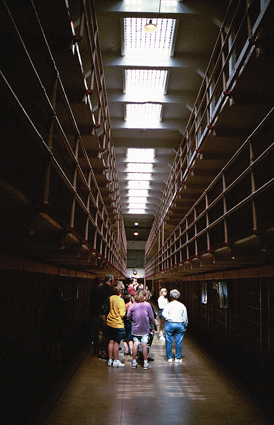

At the top of the cobblestoned switchback trail, we enter the cellhouse; it’s dim and gloomy and makes me realize for the first time the impact of the word “institutional,” a descriptor that has previously been as sapped of meaning for me as phrases like “above average” and “all natural.” Alcatraz’s cellhouse is the ur-institution, the original sin of prisons. The cellhouse has the same green-gray paint and metal stairs and deep-set, metal-grated windows as Everette L. Williams Elementary School, of which I am an alumna.

The audio tour, included in our twenty-eight-dollar admission (a refund is available if you wish to peruse the island sine duce), is dispensed to us in the cellhouse’s old shower room. The room is the size of a couple of basketball courts and to access the showers you’d have to step over a concrete curb describing an enormous rectangle in the center of the room, which we are warned not to do, for preservation reasons. To our left the site of humiliation, fear, probable trauma: the prison shower. To our right, one broken commode, unshielded from the rest of the room.

A teenager behind me says, “Man, this is cool.”

A brief history of Alcatraz itself: purchased in 1850 by the U.S. government, the island was home to generations of seabirds (los alcatraces, in Spanish) prior to human occupation. The first West-Coast lighthouse quickly followed (1854), then U.S. Army buildings and troops (1859), then the Civil War and the island’s first detainees: deserters, dissenters, and prisoners of war (1863). The island remained in use as a military prison until 1934, when the Federal Bureau of Prisons assumed control of the facilities and transformed them into a federal penitentiary for segregating exceptionally violent, influential, and escape-prone inmates from the country’s mainstream prison population. The media’s portrayal of the island prison as a “Devil’s Island” took hold during this time, and in many ways—perpetuated through pulpy films and television series like Fox’s current Alcatraz—the narrative of Alcatraz as a place of dark horrors has since become indelible.

We are not so much experiencing Alcatraz itself as we are half-living, half-creating a media event.

Alcatraz was closed in 1963 due to its high cost of operations. It sat dormant for some years as its fate was squabbled over. Per the Bureau of Prisons, “Many ideas were proposed for the island, including a monument to the United Nations, a West Coast version of the Statue of Liberty, and a shopping center/hotel complex,” prior to 1969, when a group of American Indian activists occupied the island to protest the U.S. government’s Indian policy, simultaneously ending forever the possibility of a Hilton Alcatraz. The two years that Indians of All Tribes held Alcatraz are widely considered the start of the Red Power movement, though a fire, poor living conditions, and the accidental death of a child were used to justify the eventual removal of activists from the island.

After a decade in limbo, the National Park Service purchased Alcatraz from the U.S. Army in 1972, adding to the string of real-estate parcels in the recently created Golden Gate National Recreation Area. As Carolyn Strange and Michael Kempa note in “Shades of Dark Tourism: Alcatraz and Robben Island,” the establishment of Alcatraz as a visitor destination was not without controversy:

Though the motives here seem to have more to do with concerns of taste than politics, the Director’s reluctance to play into the appeals of voyeurism is admirable. Optimistically, the NPS went ahead with its plan for polyvalent interpretation of the island’s significance, though the popularity of Alcatraz once it opened to the public and the single-minded fascination of its visitors contradicted the organization’s stated intention. The subtler narratives of the NPS’ other holdings–Muir Woods, Stinson Beach, Fort Mason–of wildlife habitats and the American Indian Movement were no match for what Strange and Kempa call “the strong currents of popular interest in Hellcatraz.” Alcatraz was “cool;” it was “creepy;” it was a chance to feel safely scared—a little like stepping into a real-live horror movie.

Observing the Alcatraz cellblocks, I get the peculiar sense of seeing a familiar image or icon in person for the first time, as though the world has become somehow more real and more artificial simultaneously. I find it difficult to separate the prison itself from its depiction on film, so in many ways entering it feels as though I am entering a movie. We stroll around silently, clustering at points of interest; the audio tour has the effect of dampening conversation, drawing us together at various nodes while discouraging interaction. No one speaks. Almost everyone holds cell phones or other devices aloft, snapping pictures or recording video. We listen to the voices of the old guards and old prisoners. We hear the recorded sound of the cellblock doors closing, and our eyes shift, our cameras shift. We are not so much experiencing Alcatraz itself as we are half-living, half-creating a media event.

All [destinations of dark tourism] seem to struggle to reconcile the morbid interests of their patrons with sophisticated historio-cultural analysis.

The audio tour focuses on the sensational: riots, escape attempts. It’s a narrative focus—some wonderfully skilled oral historian(s) obviously spent hours shaping the reminiscences of ex-prisoners and guards into precise and satisfying arcs of story. Think of a great episode of This American Life, minus Ira Glass’s lisp. There’s meat to the stories and the voices sound really, well, alive. It’s an enjoyable listening experience, and yet, the longer it goes on, the stranger the listening grows. At first it only seems odd in that way that all pure entertainment seems essentially odd, in its goal to subvert the repetition and dullness of daily life. This oddness, though, is compounded by our setting. Here, in a place with a history of inflicting extreme repetition and dullness, the refusal to dwell on boredom and monotony begins to seem almost lunatic.

I begin to think that, if the point of an authentic tourism experience (if such a thing exists) is to understand another condition closely, the Alcatraz cellhouse tour fails. The punishing repetitiveness of incarceration is utterly absent in the carefully paced rise and fall of the yarns on the recorded tour. Worse, there’s no mention of how the Alcatraz cellblock, with its dioramas meticulously re-creating midcentury prison life, might resemble or not resemble a contemporary working U.S. prison. Plenty of the visitors around me seem to think they are witnessing “real” incarceration. I sense my initial impression had more truth than I realized; what we’re taking in is closer to a film set than to county lockup.

Such ambivalence seems to be a sad commonality among redeveloped sites of human suffering such as prisons, asylums, and concentration camps, which are often categorized together by academics as destinations of “dark tourism.” The popularity of these types of destinations is enduring, the earliest perhaps being the Egyptian pyramids, the Catacombs of Rome, and the Tower of London. Today, the dark tourist’s choices are greatly expanded: for around $160, you can tour the Chernobyl zone; for $2, you can visit the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, a former high school in Phnom Penh where the Khmer Rouge tortured thousands. In 2011, when tickets became available for the 9/11 Memorial, the first days of reservations were booked solid within a few hours. Posters on Tripadvisor.com looking to visit New Orleans’s Lower Ninth Ward debate bus tours versus the DIY approach; user Mr_G_82 writes, “Anyone would have want [sic] to go to the lower 9th ward before the hurricane? maybe there are tours through the projects too?”

The experiences at these destinations vary widely. Some offer (or have tried to) balanced and informative tours, while others provide little commentary and leave interpretation to each visitor’s discretion. All seem to struggle to reconcile the morbid interests of their patrons with sophisticated historio-cultural analysis. Michelle Brown, in The Culture of Punishment, writes extensively about Eastern State Penitentiary, another former U.S. prison developed as a tourist attraction, where a mission statement intended to promote awareness and interrogation of “the tensions embedded in prison tourism” competes with super-popular Halloween fright nights, ghost hunts, and tours that place “a strong emphasis upon the most disturbing, yet anecdotal, aspects of incarcerated life.” Like at Alcatraz, the visitors to Eastern State primarily want a thrill. I begin to wonder, how could pelicans compete with that?

I keep mentioning the twenty-eight-dollar price tag to tour Alcatraz because, frankly, it’s not cheap for a stroll around a set of decrepit buildings, no matter how historic. I’m curious about the money and where it goes. As I walk from cell to cell, noting disrepair and the still-unsalvaged remains of the fire in 1970, I consider the puzzling arrangement between Alcatraz Cruises and the National Park Service. It costs nothing to enter Alcatraz, but you cannot arrive at there by private watercraft or under your own steam. There’s an annual swim from Alcatraz, but to is both historically undesirable and currently prohibited. Alcatraz Cruises has a monopoly on transportation to the island, and Alcatraz Cruises is not free. Alcatraz Cruises costs at least twenty-eight dollars. Night tours are thirty-five dollars; combination-Alcatraz-and-Angel-Island tours are sixty dollars.

The minimum wage in California is eight dollars per hour.

Federal inmates in the United States are mandated to work during incarceration, if able; they earn twenty-three cents to 1.15 dollars per hour, half of which is usually deducted for court fees or victim-restitution funds.

So what happens to the money? Some of it must go to Alcatraz Cruises, a for-profit concern with overhead. Some must go toward restoration and preservation, and it’s evident that the island has operating costs—electricity, sewage service, wifi. Presumably there is also a symbiotic relationship with the NPS and the Golden Gate Recreation Area. And then there’s that audio tour, which is professionally produced and clearly the result of skilled labor. Audio is available in “English, Spanish, German, French, Italian, Japanese, Dutch, Mandarin, Portuguese and Korean.”

If I might digress for a moment, this order of languages suggests a set of expectations on the part of the NPS. While wandering the prison’s old command center and observing a group of strangers laughing at a life-sized dummy dressed in an old Alcatraz guard’s uniform, I notice that roughly 90 percent of the visitors are white and there’s a clear concentration of European accents. I note two black visitors. I’ve found myself paying attention to race because, as previously noted, to pay attention to prisons in this country is to pay attention to almost nothing but race. Approximately one in three black men is estimated to spend time in prison over the course of his life. Proportionally, there are more than five times as many black men incarcerated in the United States as in South Africa under Apartheid. As Michelle Alexander writes, “mass incarceration in the United States, [has], in fact, emerged as a stunningly comprehensive and well-disguised system of racialized social control.”

Federal prisons are whiter than their state counterparts, and Alcatraz was a federal prison. Many of the mug shots blown up and mounted on the cellhouse walls are of white faces. Still, it seems to me that there is a non-negligible set of connections between race, ability to easily afford a twenty-eight-dollar recreational ticket, and desire to see the inside of a correctional facility. There is something of a let-them-eat-cake oblivion about paying to tour a prison. I feel foolish for not thinking of it before.

My real conversion happens toward the end of the official cellhouse tour. The audio program ends in the prison’s mess hall, where an old menu advertising stewed prunes still lingers above the serving area, and our hearty audio guides encourage us to observe the tear gas canisters mounted to the ceiling before bidding us farewell. I almost can’t believe the tour is over; it feels a little too half-baked to be ending here, no one having breathed a word about prison being anything more than an extended time-out, with a few Rube Goldberg-esque escape attempts thrown in to liven things up—certainly not an experience with long-term psychological and socioeconomic repercussions. Certainly not an experience that continues today, in worse conditions and for many, many more people (by which I mean more poor people and people of color).

Lots of visitors have taken this moment to sit on the benches placed throughout the mess hall and talk. Have you ever gone to a screening of an artsy movie around Oscar time in the suburbs and listened to dozens of middle-aged people come out of the theater afterward and declare it interesting? The very same people find Alcatraz interesting—and creepy and spooky and giving of the heebie jeebies, to boot. There’s a certain distancing required to get the goosebumps at Alcatraz (instead of just getting sad or somber or pissed the fuck off), and all around me people are distancing themselves from the experience of prison with ruthless efficiency.

I drag Mom out of the mess hall and downstairs to return our audio tours. At the return station we’re presented with two options: we can enter the gift store, or we can enter an exhibit on the American Indian occupation of Alcatraz, We Hold the Rock. Hardly anyone goes into this latter room; it’s poorly laid out, and it’s difficult to want to spend more than a couple of moments looking at bad video collage and deciding to read more later. Instead our fellow thrill seekers are streaming into the door on the right, to the official Alcatraz Island gift shop, to buy postcards and DVD copies of The Rock and t-shirts with U.S.P. ALCATRAZ REGULATION #5: YOU ARE ENTITLED TO FOOD, CLOTHING, AND SHELTER. ANYTHING ELSE YOU GET IS A PRIVILEGE emblazoned on them. What this article of clothing is supposed to suggest about its wearer is relatively obscure; luckily, back in the seedy shops at Fisherman’s Wharf, visitors can also purchase ALCATRAZ SWIM TEAM shirts and straight-up old-timey, striped “jailbird” tops and bottoms—and onesies—for maximum clarity of message, i.e. Prison is so far removed from my life I find it an amusing joke. Also available in the official gift shop are Alcatraz-replica tin spoons, mugs, and cafeteria trays; the usual magnets and key chains and shot glasses; and a bewildering array of memoirish books with titles like Last Guard Out, The Children of Alcatraz: Growing up on the Rock, and Alcatraz Schoolgirl. Alcatraz Schoolgirl!

Exactly at this instant, I hear again the voice of the sandwich woman from the Alcatraz Landing Café, and this time she’s saying, “Prisoners today should see those cells. Then they’d stop complaining! We pay fifty thousand dollars a year for them to sit around. In Alcatraz they’d really have something to complain about!”

In the 1980s, the National Park Service attempted to develop some progressive exhibits addressing not only alternative histories, but also issues like human rights. Strange and Kempa write that lefty rangers developing and promoting these projects faced censure:

[Those in isolation] are not always the prisoners who have committed the most heinous crimes; often, they’re simply the ones who have adjusted most poorly to life in a correctional facility.

The offending exhibits gradually disappeared. The combined pressure from the Bureau of Prisons and from ticket buyers fascinated with the macabre has resulted in the Alcatraz experience today: twenty-eight dollars for a polished, politically tepid audio tour of the cellhouse, unstructured access to the island’s grounds, and several studiously “unbiased” exhibits on other aspects of the islands history.

These latter exhibits are not mentioned on the audio tour—Mom and I encounter them later, on our way back to the ferry—and are located away from the main cellhouse. They’re located underground, in a warren of small rooms carved out of the rock. “Alcatraz and the American Prison Experience,” one of these small projects, was built and maintained by an inmate work crew from a federal correctional institution in Pleasanton, California. Water drips from the ceiling outside the room, pooling on the uneven floor. The exhibit itself contains no interrogation of the ethics of prison labor. A plaque on one of the walls reads: “This cooperative work program between the National Park Service and the Bureau of Prisons has proven very successful.” More than 1.3 million people visit Alcatraz Island each year. The day we visit, all of the exhibits outside the cellhouse are empty.

When Alcatraz closed in 1963, much of the prison population ended up at a high-security institution in Marion, Illinois. Marion was thought by many to solve the problems of Alcatraz—chiefly the high cost of operation and the inmate behavioral issues. Inmate violence escalated dramatically in the 1970s, however, and Marion soon adopted a control-unit mentality, transitioning to the United State’s first “supermax” facility in 1983. At supermaxes, inmates are kept in solitary confinement for all but one or two hours per day. Twenty-five thousand U.S. prisoners are currently kept in near-continuous isolation at such institutions. Twenty-five thousand. These are not always the prisoners who have committed the most heinous crimes; often, they’re simply the ones who have adjusted most poorly to life in a correctional facility. Some inmates have been in isolation for more than a decade. Studies of long-term isolation have shown strong correlations to mental instability and incidences of psychosis.

There are no tourists at places like Marion, which now houses a communications management unit (CMU), where the mostly Arab-Muslim prisoners’ phone calls, emails, and visits are severely restricted and monitored daily. Daniel McGowan, an environmental activist serving a sentence for domestic terrorism, writes for the Huffington Post that the Marion CMU is “a punitive unit for those who don’t play ball or who…express political beliefs anathema to the [Bureau of Prisons] or the U.S. government.” Another facility, Florence, which opened in Colorado in 1994, was built from the ground up to be a supermax. It’s often called “the Alcatraz of the Rockies.” All prisoners inside are housed in 86-square-foot cells; hunger strikes and suicide attempts are not uncommon. The prison operated for thirteen years before allowing select members of the media inside in 2007. The Bureau of Prisons has a history of refusing to cooperate with the press and denying scholars access to inmates at institutions like Marion and Florence, a denial which prevents research both on the effects of solitary confinement and on the etiology of crimes like terrorism. Limited access also curtails the public’s information. Limited information makes it easier for prisoner’s rights to go on being abused, day after day, week after week, year after year.

As the ferry returns us to Pier 33, I stare at an announcement about Alcatraz Cruises’ Hornblower Hybrid, apparently the nation’s first hybrid ferry. The Bay Area’s commitment to environmentalism verges on the monomaniacal. San Francisco will soon have a city-wide zero-waste policy; composting and recycling have been compulsory since 2009. Plastic bags were recently prohibited. At the time of this writing, city departments (and parts of the University of California system) are considering banning Apple computing products after Apple announced its intention to withdraw from an environmental certification process. The resources behind all of this action are evident—a cursory look at the job posting site, Idealist, shows 296 current openings at environmental non-profits in the Bay Area. Total number of openings tagged “prison reform”: 1.

I am not suggesting that it’s possible or feasible for the NPS to radicalize every visitor to Alcatraz Island. I am suggesting we bother to learn enough to radicalize ourselves.

Christopher Glazek writes in N+1, “There’s no use saying that progressive goals aren’t in competition with one another. They very surely are, and criminals have lost that competition again and again, with tragic results.” Atul Guwande, writing on solitary confinement in the New Yorker, argues, “In much the same way that a previous generation of Americans countenanced legalized segregation, ours has countenanced legalized torture.” The same folks I see caring passionately about green energy (and Planned Parenthood and education policy and microlending) may never have heard of Nutraloaf. They may know nothing at all about the prison farms in the American South; they may even be inclined to enjoy The Dark Night Rises, this summer’s blatantly right-wing piece of propaganda that simultaneously vilifies prisoners, the French Revolution, and the Occupy movement. So why is it that we care about endangered species more than certain endangered humans? And how can that balance shift?

The reasons for ignoring prisoners are easy to understand: they’ve had a hand, sometimes more, in their fate. As my mother will say to me later, at dinner, by way of indicating she’s had enough of this line of conversation: “Well, I don’t know, those were some pretty bad people who did some pretty bad things.” It is true; prisoners are not usually precisely good. Often they are thieves, murders, rapists, embezzlers, terrorists. Yet we continue to think of ourselves as good when we inflict suffering back on these men and women. A start would be for us to recognize the hypocrisy of our own beliefs.

But first, there must be knowledge. I look at the Hornblower Hybrid flier and ponder the missed opportunities at Alcatraz. Here is one of the few social spaces in the country where people with real political power (those who can vote, have disposable income, etc.) seek out information about incarceration; it’s a disappointment that what they get instead is entertainment. The real problem is our complacency, and perhaps it’s bigger than any tourist attraction could hope to correct. We need politicians who aren’t afraid to voice progressive, even radical, stances. We need prominent religious leaders who preach tolerance and acceptance. We need integrated communities so oppression is not so easily silenced. We need citizens who read and listen and who think critically and pay attention.

To be clear, I am not suggesting that it’s possible or feasible for the NPS to radicalize every visitor to Alcatraz Island. I am suggesting we bother to learn enough to radicalize ourselves.

I go back to Alcatraz three weeks later, with a photographer in tow. I want to make sure I haven’t exaggerated anything—I want to confirm the striped onesies and the awful commentary. This time the sun is shining, and the day is warm. Many elements of the Alcatraz experience are different, and the first one we encounter is an unexpected, apparently-required photo-portrait before setting foot on an Alcatraz Cruises vessel. The photo station is set up in line to board the ferry and has a gorgeous scaled image of Alcatraz and the San Francisco Bay at sunset as a backdrop. Prints are for sale later. It’s a lot like getting your photo taken at prom. My photographer and I turn away at the moment of exposure, a small rebellion against the mandatory mug shot. I wonder, bemused, “Does Alcatraz Cruises really not recognize the irony in photographing everyone who is visiting the island?”

On the ferry, I eat a soft pretzel and look around to confirm my extremely smug hypothesis that everyone will be white. This time, everyone isn’t. There’s a large group of young Japanese tourists and several Latino families. There’s the general air, as we approach the island, of festivity. It’s hard even for me not to feel enthusiasm; when we disembark the ferry, the dock is buzzing with activity, including some kind of scout troop lugging sleeping bags and camping materials up the thirteen-story hill and a band of historical reenacters in Civil War-era garb milling around the parade ground. The gentle ridiculousness of adult men who grow beards for their hobbies is heartwarming, even to me.

On tour this time, I skip the audio, and I make a conscious effort to stay a few yards away from the bulk of the group with which we entered the cellhouse, whose movements are synchronized by the directions on the taped tour. It’s easier to pay attention to my surroundings this way, and I find that it’s also easier to keep my frustration at bay. By the end of the first hour, I’m actually managing to enjoy myself. Near the solitary cells (D-Block), we discover an uncanny resemblance between my photographer and Al Capone. A volunteer offers to lock my photographer in “the Hole” for a few moments, and as soon as the door shuts, flirts with me in an avuncular way. He tells me his son filled out his volunteer application and that he’s met several celebrities (the only one he names is “Booger from Revenge of the Nerds”) while on duty.

After the tour ends, I chat for a while with a docent, who works with the Golden Gate Conservancy, the organization that raises funds for and administers the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. I ask about a prior exhibit I learned about online, developed in conjunction with San Quentin’s Prison University Project, and she tells me about it in laudatory tones. She mentions there’s an upcoming exhibit on restorative justice later this year. Feeling comradely, I tell her what I’m writing about, and at first she expresses excitement, but then she says something puzzling: “Oh, you should write about the victims!”

“The victims?” I say.

She says yes, the victims; none of the exhibits or tours mentions the victims, and it has always bothered her. So steeped am I in my own polemics that for a moment I actually think she’s referring to the old inmates as victims.

I want to tell her everything I’ve learned in the past few weeks: the triple bunks in San Quentin, the sickening “We Have the Time to Do It Right” motto of many prison-industry operations, the recidivism. But I can’t. My good mood evaporates. I’m suddenly exhausted, faced with the embodiment of what the rest of the world seems to think: that revenge is the same thing as justice, that the only people who have rights are the ones who’ve followed the rules.

S.J. Culver is a writer, teacher, and tenants’ rights counselor whose essays and reviews have appeared in the Chronicle of Higher Education, the San Francisco Chronicle, the Minneapolis Star-Tribune, The Awl, and The Rumpus. More work can be found at www.sjculver.com.