For many years now, Osman Samiuddin has had an unmoving place on the list of writers whom I will always read no matter what they write. My love for the game of cricket, and also for smart, snappy writing with huge depth beneath its surface gleam, come together in Osman, long regarded as one of the game’s finest writers by aficionados of cricket journalism. One evening in London, where we were both living at the time, I heard him talk about a non-cricket story he had been pursuing: that of a Pakistani guitar genius from the 1970s, with the biopic-worthy name Iggy Fernandes, who’d died under mysterious circumstances while still in his twenties. I was interested in the story of Iggy—and then, when I realized that Osman’s interest had become consuming without him ever having heard a note of the man’s music, I became even more interested in what he could write about the nature of obsession: why it arises, why it takes the form it does, what it reveals about ourselves if we look deep into it. It was an act of absolute selfishness to commission him to write this piece: I’ve been longing to read it since that conversation with him, years ago. – Kamila Shamsie

—

There I was, one Saturday evening in July eight years ago, inside this dimly lit club in Karachi, looking for a man who had been dead for over thirty years. On a low stage a heavy-set man—mid-sixties, red bandana around his forehead and long but thinning white hair—was leading the band in an energetic rendition of The Doobie Brothers classic, “Long Train Running.” This was Captain Akeel, the evening’s impresario, lead guitarist and, for forty years, an airline pilot. He looked like an extra from the set of a Cheech and Chong film who’d taken a wrong turn in 1978 and landed up straight at this gig. On the dancefloor, a lean man was giving it some. And I mean really giving it some. He was also in his sixties with a silver mullet tied up in a tiny, apologetic ponytail. He was doing the Mashed Potato, a slick, rapid dance that will not be found with your roast dinner. With some élan too, his lower legs and feet gliding in and out like he was on roller skates.

Occasionally, in between songs, the Captain would walk through the crowd in a reverie of sorts—high-fiving, backslapping, to see to a matter requiring his attention at the front door perhaps, or at the rudimentary bar on one side of the room. Actually, “crowd” is a bit much; there were maybe seventy people there that evening, well-heeled and mostly of the same generation as the Captain, milling around bar tables. Also, actually: only under the most elastic definition could this be called a club. This was Captain Akeel’s home, a sprawling bungalow off Sunset Boulevard—the most ambitiously named road in all of Karachi, which, most evenings past midnight, smells like it is rotting because it is on the route through which fish is transported in the port city.

Some years earlier, after his family emigrated to Australia, Captain Akeel knocked down the walls of the entrance hall and adjoining living areas and had the space soundproofed. He wanted to turn his home into a Hard Rock Café, or at the very least a place where he could jam unhindered with his friends. Word got round about the sessions, and they gradually grew into slightly bigger invite-only evenings. He gave it a name: Club 777, after the Boeing 777s he flew.

What Club 777 really was, though, was a simulation of Karachi’s nightlife as it had been in the 60s and 70s. A period celebrated as a cultural heyday of sorts, its absence lamented in countless WhatsApp forwards and Facebook posts, and through occasional features and documentaries. You’re probably familiar with the tone accompanying these, of gentle incredulity and deep sighs: photos of (gasp) Karachiites drinking alcohol in bars, women in (OMG!) short skirts, hippies in hostels (wow) smoking weed; look, look at how we used to be, how we were so not what we are now. Smartphones no doubt ping similarly in Kabul or Tehran. The majority of the people who came to Captain Akeel’s were those who had lived and experienced the real thing.

And here I was, pity-laughing at dad jokes and searching for a dead man. Well, I was looking for a trace, a whiff, a rumor—anything that would bring alive the greatest guitarist you’d never heard about.

***

I first came across him in a Pakistan newspaper column and the name struck me—as the kids have already abandoned saying—right in the feels. “Iggy Fernandes.” How could it not, with such a rockstarry formulation? The sparse biography sealed the deal. A genius guitarist from the 1970s, the best Pakistan had heard till then. Plunged to his death from the roof of Hotel Metropole—once a hallowed landmark of Karachi nights, now a hollowed-out ghost building parading as a roundabout—after his heart had been broken by a girl. I can’t be sure now whether there was a picture but if not, I came across one soon enough. Iggy was wearing, other than some swag, an Afro and a leather jacket and holding a guitar left-handed. Maybe you’re forming the impression that I did then, of a Pakistani Jimi Hendrix.

The details would turn out to be wrong, but even such a thin sketch was compelling, crying out to be filled in. If he was a Pakistani Hendrix, why was so little known about him? Why was he so acclaimed in the first place? Had he left behind music we could listen to? Was it really suicide—because, morbid as it might seem, nothing begets a rock legend more than suicide? What happened with the girl?

It’s been sixteen years since I discovered Iggy and started looking for answers to these questions. Some years I’ve looked harder than other years. I’ve met former bandmates, his friends and fans, musicians taught by him, some family. I’ve travelled three continents in this search. I’ve swung between thinking it’s a great story, or that it’s a story not about him at all, or that it’s no story—and I’m still not sure. I’ve gotten married, had two daughters, changed jobs, and moved countries multiple times, carrying Iggy with me. Friends who know ask me about it, sometimes as if Iggy is my third child—which, in a way, he is. I’m at the point now where I struggle to explain to people why, or even whether, I’m still chasing the story.

So, it’s probably easier to begin by trying to explain why I fell so hard, so deep, for the story in the first place.

I’d been in Pakistan for six years by the time I read that piece, having never lived there previously. I can’t say that I was especially confused or angst-ridden about my identity, but it’s also true that I was Pakistani not because I felt it, but because I clearly wasn’t anything else. My parents were Pakistani. My passport was Pakistani. By default, I was Pakistani. Karachi was more or less my annual summer holiday destination, so it wasn’t foreign. In fact, coming from the Gulf, it used to feel like an escape. In my teens, none of this was complicated.

I wouldn’t say that subsequently living there, across my twenties and thirties, was more complicated. But there was a sense underpinning the years I spent there that I didn’t think about, let alone attempt to articulate until much later, after I had moved out of Pakistan. I didn’t even know I was waiting to be diagnosed until Ijeoma Umebinyuo, a Nigerian poet, diagnosed me with “Diaspora Blues” with devastating and lyrical succinctness:

So,

here you are

too foreign for home

too foreign for here.

never enough for both.

Now I’ve rarely taken the rootlessness in the poem as a lament, let alone a torment. Some days it can feel like an aspiration to be of nowhere in particular, to not have to be enough for anyone, to have the freedom to not be bound by home or here. I don’t see it as a permanent affliction either—which is, on reflection, the privilege of being an expat rather than an immigrant or displaced person. If you’re moving roughly every decade, everywhere is foreign and everywhere is home.

But in the moment of being either at home, or in the place that isn’t home, life can be about finding ways to be enough—and I guess Iggy was, at a basic level, a way for me to be enough for Pakistan. Just as I was Pakistani by default of not being anything else, so it followed that Pakistan was, by default, home—or, at least, more a home than the other places I had lived. Working as a cricket journalist already afforded me a deeper in with the country, because in many ways, cricket remains the clearest lens through which to see Pakistan. And in writing a history of the game there, I learned more about the country than any curriculum could have taught me.

But cricket was everyone’s in Pakistan. I wanted something that was mine alone, because Karachi was the first place I didn’t think of as one I would inevitably move on from. I wanted something that would make me so not-foreign that I could say this was home. Wherever we are, really, we all seek something that can be ours, something that tells us we belong: the tiny hole-in-the-wall eatery nobody else knows about; the work of an undiscovered local artist; an untouched holiday spot; a band that is blowing up but has not yet hit the mainstream; even an unmapped shortcut that cuts a route in half. The hidden entrances into a place that nobody else knows—that allow you into a part of the place nobody else has been to. They’re your little secret, binding you to the place and maybe telling you something about it that only you can know.

And so, I look back now and can see that all I wanted was for Iggy to be my little secret with Pakistan.

***

It took me years to do anything about Iggy other than let the idea of him grow in my head. When I first read about him in 2007, Pakistan was beginning one of its periodic convulsions. The early 2000s had been a period of relative calm, but in hindsight it’s clear Pakistan was fake-smiling its way through, hiding the turbulence underneath. The fallout from the country’s long-doomed strategic meddling in Afghanistan, as well as the consequences of 9/11, were creeping up on it. They would spit out hell over the next few years—a time pockmarked by a maelstrom of terrorist violence and provincial insurgencies that took the lives of tens of thousands, a messy transition from military to civilian rule, and all manner of political crises.

I had moved out of the country by 2012, which was when I watched Searching for Sugar Man and was energized in my own search. That is a great story: Sixto Rodriguez, a Mexican-American folk musician from the 70s, bombs in the US but strikes it big in Apartheid South Africa and then vanishes. Two South African fans trace him down years later, a recluse working on construction sites—thereby disproving wild rumors that he died on stage and helping to resurrect his legend. Iggy was definitely dead, but could I pull him out of obscurity and make him my Pakistani Sugar Man?

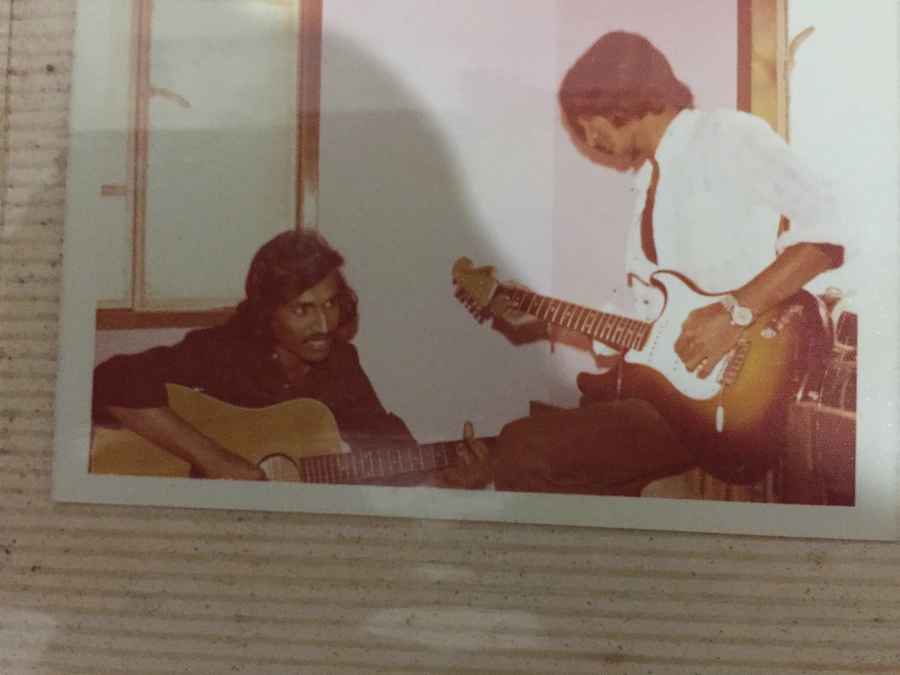

I sought out Maxwell Dias, a neighbor to, and bandmate of, Iggy. Max, who has since died, was a renowned guitarist (he was the one who invited me to Club 777, where he was part of Captain Akeel’s band) though he couldn’t have looked less like one. Bespectacled and portly, wispy hair in a neat side-parting, if he rocked anything it was the Unironic Uncle-core aesthetic. Max knew everyone and their story in that 70s scene of which he was the spiritual keeper—along with his daughter Lynette, who runs the Legendary Musicians of Karachi blog. (In its exhaustiveness as a resource and the homage it pays to the bands, musicians and venues that brought Karachi alive, it is itself legendary.) When we met in Max’s flat in Saddar, the southern Karachi district that was once ground zero of the 70s music scene, he remembered Iggy with an awe undimmed by the three decades since his death.

The two had played together at a prominent club sometime in the mid-70s, although as with all bands then, they only played covers of the popular music of the day. They produced no canon of their own. This would be one of the frustrations in searching for Iggy. Rodriguez may have been lost but he left behind albums and epic concerts. He had been a public figure, unlike Iggy who left no footprint. Pakistan’s music scene when Iggy was alive was heavily skewed toward its film industry. That was where original music was made, not in the hotels and bars. If the genius guitarist didn’t have any original music to show, what was I looking for? How could I know he was a genius if there was no output of that genius?

But two things Max said kept me hooked. First, he confirmed—if somewhat cryptically—that a girl had broken Iggy’s heart, leading to his death by suicide. Then, as he began to explain how Iggy had gotten so deep into guitars, he paused. I wasn’t sure whether he was weighing up the right way to say what he wanted to, or whether he was rethinking if he wanted to say it at all.

Eventually he did.

“He was too good to be a good guitarist, you know? There had to be something wrong with him to be that good.”

Max, I would learn, was no-nonsense. He played things down, not up. He paused, asked me to turn off the recorder, and then, lowering his voice in a way that suggested God should not hear this, whispered:

“We used to think he must have sold his soul to the devil to be that good.”

The Faustian pact is a well-established trope with origins in the Bible. So it wasn’t totally weird that Max, a practicing Christian, was inclined—perhaps even predisposed—to think in those terms. Or that several other musicians, also from the Goan Christian community that dominated the scene, would refer to Iggy’s talent similarly. It was such a tantalizing evocation of genius—that you had to have done something terrible in return for it—as well as one that I recognized. One example: Robert Johnson, an acclaimed 1930s bluesman from the American South. In death, Johnson is feted as an influence for the likes of Eric Clapton, Keith Richards and Bob Dylan. In life, he went largely unknown, and whatever renown accrued was from nomadic performances at blues joints or on street corners. His recorded output is tiny, inversely proportional to its influence.

As much as his music lingers, so does the myth of how Johnson became such a master. One dark night, it goes, during a period of his life that is unaccounted for, he stood at the crossroads—of life, of worlds, of actual roads, who knows?—and came across the devil. Johnson, until then derided as an ordinary musician, made the deal: his soul in exchange for mastery of the guitar.

Johnson is not alone in having inspired such mythmaking. He’s not even the only blues musician about whom this has been said—Tommy Johnson, unrelated but contemporaneous, has been cited as the original seller of his soul.

For a while, the more I researched Iggy’s life, the more I heard echoes of musicians I’d spent my adolescence fascinated by—echoes that placed Iggy in the category of the genius musician. Everyone who played with Iggy or heard him was convinced of his genius. He could listen to a piece of music and replicate it within minutes. And then riff on it. People concluded that he had perfect pitch: the rare ability to instantly identify by ear a note or a chord. He learned by holding the guitar upside down because he was left-handed and his first guitar was a right-handed one. He would later get the right guitars, but he could—and often did—still play the wrong guitars upside down. At one talent show, he played while holding it over his head. And there was also the sudden—Mephistopholean?—transformation where, forced indoors during the 1971 war that led to Bangladesh’s creation, he locked himself in his room as a beginner and a few, intense months later, emerged a guitar maestro.

In the absence of any recorded music, I latched on to anecdotes of jam sessions at his home, where the city’s musicians congregated to hear him. In my mind, stories of these jams were the validation of his legend, partly because they struck very rock n’ roll notes. I placed Iggy’s impromptu sessions—that only a few bore witness to, but spoke of in reverential tones forever after—on the same plane as those seminal concerts in the pre-internet age that were a band’s breakthrough, or their farewell, or the mark of a triumphant comeback, and that everyone swore they were at even when they weren’t. Iggy was, I also learned, painfully shy and socially awkward.

The day I worked out he was twenty-seven when he died, I could barely contain myself. Twenty-seven, for those even passingly familiar with pop culture, is music’s most resonant and tragic age: Hendrix, Cobain, Joplin, Morrison, Winehouse and Robert Johnson himself all died at twenty-seven. He had no music I’d heard, but in my head Iggy was becoming an amalgam of them all.

***

I wasn’t in Pakistan when the first pop and rock wave washed ashore in the 90s. I heard and loved those first albums by Vital Signs and Junoon, the two defining bands of the era, but because I was not living in Pakistan at the time, my experiences missed something vital. I’ve always thought of music as a place. At least, in its consumption—in the sense that each time we listen to a favorite song or album, it takes us to the place in our lives where we first heard and loved it, where it first meant something. We keep going back there because we want to experience something that means that much again, or because we want to dig deeper into the meaning. And in its creation—as an expression of the interior and exterior lives of its creator—a piece of music obviously can’t help but be a place.

Place doesn’t imply boundaries, of course. On the contrary, music is defined by the opposite: that boundaries are irrelevant to its travel. But it’s perhaps true that being there, where the music comes from, strengthens our ties to it, if only because we’re more acutely sensitive to the urges and surges behind its creation. This is why all the great music scenes and eras weren’t only about what fueled the creation of that music. They were as much about those who received it, and how they were processing it. It’s this idea of place that ties both our sense of belonging and ownership to music—to a lyric or a song, an album, a moment, a movement, a tribe, an emotion. That’s why music—art, generally—and sports can feel so unique, because there is none of the tension between belonging (the submission of oneself) and ownership (the assertion of oneself) that is inherent elsewhere in our lives. We own music, just as we belong to it.

The place this wave was coming from in Pakistan was one of seismic change: after eleven stifling years of Zia-ul-Haq’s military rule, the return of democracy in 1988. It would get messy later and Zia’s death did not mean the end of Zia, but that moment, I think now, must have felt like one long, glorious exhale. Even if a lot of the music wasn’t especially political, it was one of the ways through which Pakistan defined itself for what it now was, which was stridently Not Zia.

But I wasn’t there. I didn’t drive around Karachi’s seafront with friends, soaked in this music. I wasn’t dissecting lyrics in friends’ bedrooms in Lahore. I couldn’t watch music chart shows on NTM, the shiny new channel that wasn’t state-owned. I didn’t make a mixtape for my crush from those songs. Well, I could’ve done some of this where I was, but in the unchanging, absolute monarchy of Saudi Arabia, would it have hit quite the same?

All the music I did grow up listening to—the music that I loved—lacked rootedness. It didn’t diminish my love for it. Art can, after all, be enough by itself, without context. And I do ascribe some transplanted sense of place to it all: freaking out to the hyper west-coast funk of the Red Hot Chilli Peppers in the stillness of Jeddah; decoding the brooding psychedelia of The Doors at a shiny, happy family wedding in Karachi; sulking in the deep, abiding grey of grunge or The Smiths, in the deep, abiding grey of north England. All music is a place. It’s just more vivid in some places.

Just as the end of one dictatorship produced a burst of Pakistani music (to be clear, Pakistani music throughout this essay is its western-influenced oeuvre), so too did the start of another. The liberalization of electronic media under Pervez Musharraf in the early 2000s birthed a genuinely stirring and diverse music scene. And this time I was there. This was Pakistani music that I recognized and that recognized me back. I was adulting in earnest and like some of the music, I too was giddy with the sense of newness and liberation and opportunity.

I did a radio show for a while where I felt insidery, because I could play local music. I played stuff that I loved and stuff that I could be snide about. I got the themes behind these lyrics and videos. I understood the different genres and their subcultures: rock, rock-adjacent, rap-rock, trip-hop, electronica, pure pop. I was thrilled that there were songs that spoke to the angst and confusion of a society being shaped again by internal pulls and external pushes. I felt the heat of live performances. This connection, this sense of place, meant that even after I left Pakistan, I kind of stayed there.

It was also a propellant context for Iggy. Because on realizing Iggy had no published work, one of my first thoughts was: What if he had been born twenty years later? The family and contemporaries I met would speak of his frustrations. Playing covers in hotels was no platform for his talent and ambition. There was no other outlet, not on TV or radio or vinyl. Of the twenty to thirty bands that worked Karachi’s hotel and bar circuit in the 70s, only one ever produced an album of original work (Soz-o-Saz—better known as the band Like Harvest—with their four-song release of psychedelic/progressive rock through EMI Pakistan). It lives online as a rare, exotic curio.

The imposition of prohibition by the prime minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto in 1977, and the subsequent arrival of Zia, killed the hotel and bars trade. Even that limited platform was now gone. Iggy wanted to get out, to join the mass exodus of fellow musicians. Intriguingly, he landed up in Egypt for about eighteen months in the early 1980s, with David Fredericks, a suave lead singer who had already moved from Karachi. I yearned for this to be some epic sojourn, where Iggy ran riot around Egypt, a trail of trashed hotel rooms behind him, and an outpouring of his talent and frustration into a batch of legendary lost recordings. It was not. Once again, he was restricted to playing covers, though at least it was at a beachside luxury hotel in Alexandria.

If he had been around in the 2000s, with its relatively abundant opportunities, who knows how he might have flourished?

***

It is deeply absurd, I know, to wonder whether a musician would have fared better under one military dictator than another. It is actually deeply Pakistani—a people for whom a military dictatorship is merely the symptom of the broader condition that is Pakistan. Which—as we pull out the old quip from a safe distance—is that while all countries have a military, with Pakistan, the military has its own country. They’ve ruled officially for thirty-three of the country’s seventy-seven years and the rest of the time, they’ve let the civilians think they’re running the place.

It is also a deeply nostalgic question, and nostalgia, in case you haven’t noticed, has been backseat-driving this all the way through. The column in which I read of Iggy was an exercise in as much, part-history lesson and part-hagiography of 70s Pakistan. That decade—or the portion of it not under military rule—holds an enchanted, even fetishized, place in the imaginations of a certain constituency of Pakistani. Specifically, Karachi in the 70s: less harried, less uptight, less at odds with the world than now; this idyllic recollection funneled through the bustling night scene of hotels, bars and clubs, where people made life and musicians like Iggy made music.

Every single person I met about Iggy spoke so evocatively—and some of the recollections were so powerful—that I started experiencing anemoia. The word isn’t in conventional dictionaries, but it means nostalgia for a time you haven’t actually lived through. It was coined by John Koening ten years ago, for his beautiful, elegiac blog (and now book) The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows—which gives us words for emotions we have been unable to describe. (For those of you who aren’t American or haven’t been to the US but are fans, as I am, of Netflix’s sci-fi hit Stranger Things, anemoia is exactly what you feel watching it.)

The stories feeding the anemoia belie the vaster reality. The 70s were a pivotal decade, even if in Pakistan each day feels acutely pivotal, weighed down by the cumulative history of all the days that preceded it, as well as its inevitable contribution to all the history to come. In many ways it was shaped by Bhutto, the man who led for much of it, with his slipperiness of being this but also that, of being that but also this. Behold: the first genuinely democratic and popular leader, and also the first democratically-elected and populist autocrat. A leader with a feudal background and an entitled upbringing, preaching socialist politics. Power-hungry, and an enabler of the power of the masses. A leader who openly enjoyed alcohol, and the leader who imposed prohibition.

This, remember, was a decade that began with the country physically halved—a belated, bloodied acknowledgment of the frankly ludicrous idea that Pakistan could be one country separated by thousands of kilometers of enemy territory (never mind one where the injustices heaped by the western wing upon the eastern one only widened the fissure). Bhutto’s socialism may have been a justified response to the growing inequities of the preceding decade, but it was a radical shift nonetheless. There was a full-blown insurgency in one of the provinces, and the state was weaponizing Islam against minorities as well as in its politics. And then it pivoted back to military rule, as it had begun. A time in which the country was pushed and pulled apart like this, you can imagine, hardly made for a golden time.

But would 2000s Pakistan, which I lived through, really have been better for Iggy? Though not nearly as well-set, there exists, I suspect, a bit of collective nostalgia for this mini-period as well. I look back on the time with fondness—perhaps even the most I have felt for any of the places I have called home. The industry I was in was thriving. A credit-fueled spending boom sheened the economy. There was relative security in the cities. 9/11 had seen a brief brain-gain of accomplished Pakistanis returning from the West. I’d like to imagine that Iggy would’ve found more exposure, perhaps more fulfillment, in an industry that was built better for it. Maybe he would’ve played concerts to big crowds and released albums to mass acclaim. He might have made a reasonable living.

But just as the nostalgia for the 70s is slightly myopic, so too is this idealization of these years of Enlightened Moderation, as Musharraf called them. That was a neat if vacuous bit of wordplay that aimed to place Pakistan at the forefront of global Muslim self-introspection, after 9/11. Meanwhile, at home the state was floundering against growing militancy, letting extremist thinking set in society like cement, and fanning sectarianism—everything, in fact, that would yield the exact opposite of enlightened moderation. Ignorant Excessiveness? If only it was that benign. As with all dictators—soft, medium or hard—Musharraf’s chief concern was clinging to power. So no, much like the 70s, this was also a poor meringue of an era with the sugary top—Bars! Music channels!—merely masking the hollow beneath.

Pakistanis are far from the only arch-nostalgists. The past is better, pretty much all the time and everywhere, even when it quite evidently isn’t. But in Pakistan nostalgia does feel a little like PTSD, each generation clutching to their own era as if it were flotsam in the ocean. They understandably hold on to it for dear life, as it is what keeps them afloat. Except nobody’s looking at the big wrecked and sinking ship in the distance.

There’s a sad, echoing coda to this question of whether Iggy would have been better served by the 2000s, in the life and times of Amir Zaki, whose career spanned four decades starting in the mid-80s. In some ways Zaki was the Iggy of his day, a brilliant, autodidactic guitarist, so brilliant that people found it difficult to keep up with him. Zaki made it to a degree and in a way Iggy could never have, releasing a couple of albums and playing in the biggest bands (Vital Signs among them), though never for long because, creatively, he was wired different.

I wanted to speak to him because I’d been told he had seen Iggy play and may even have been a student. On a trip to Karachi in 2015 I messaged him hoping to talk about Iggy. Zaki famously went through periods where he disappeared from view, so I wasn’t hopeful. He replied quickly though, acknowledging he knew Iggy but explaining that he had been advised by his doctor to not talk about suicide.

It was a slightly disconcerting response (I had not mentioned Iggy’s death), but Zaki’s problems with addiction and depression were fairly well-chronicled. He was perennially frustrated with the industry and was financially unstable. Two years later, in June 2017, he passed away from heart failure. He was forty-nine.

***

Egan “Iggy” Fernandes was born in Karachi on July 31st, 1956, the youngest of three brothers. The other two brothers were Ryan and Dolan. Dolan had retired and emigrated to Australia, to Woollongong, a university city about fifty miles outside Sydney. I met him there in January 2017. We had been exchanging texts for several months. He was happy to meet but we had agreed not to talk about Iggy’s death or its circumstances.

Dolan was small and slight but, he would tell me, still taller than Iggy. He looked frail and was walking with a stick; he had recently undergone a bout of chemotherapy. He emanated warmth and in his milky, greying eyes, some empathy.

Dolan would fill in the details of Iggy’s life. An unremarkable childhood. Not academically inclined. Left school at sixteen. Super bright. Iggy played plenty of cricket where he had a bat, a ball, a set of stumps and thus also entitlement. Getting him out didn’t always mean his batting was over. He was a crosswords fiend. Dolan remembered a clue Iggy solved for him once. I had never come across a subject who was remembered through a crossword clue. They weren’t a musical household, but Iggy was given his first guitar, an acoustic, by what Dolan called “shippies”—friends who travelled around the world as crew on ships, who had brought it back from Malaysia.

One of Iggy’s first influences was The Beatles’ Abbey Road LP, which he learned to play in its entirety, more or less by simply listening to it repeatedly. He developed a taste for Deep Purple and Led Zeppelin but also for Santana, Chet Atkins and John McLaughlin—rock gods but also virtuosos who didn’t just play the guitar, but made a study of it. Dolan told me of Iggy’s first live performance at a talent show at the Christ the King Church in Karachi. He was barefoot on stage and played Zepellin’s “Whole Lotta Love.” He blew the crowd away.

Dolan showed me some photographs of Iggy, my first proper sighting of him. It was slightly underwhelming in the way real photographs of ordinary people generally are. You couldn’t tell he was unusually small because he was with his brothers, who were small as well. But he had the unmistakable grin of the indulged youngest child.

If Iggy had been American this would have been so much easier. Whether or not they are famous, from the moment they are born to the moment they leave, Americans are on camera, living life in preparation for the eventuality—perhaps inevitability—that one day somebody will come and want to make a film about them. No such luck here. No video footage from a birthday, no clip of Iggy playing the guitar in his room or goofing around with friends.

Dolan suggested we move to his living area, an outbuilding in the garden. I thought he might have more photographs to show me. He didn’t. He had some recordings of Iggy’s music that he wanted to play for me. Maybe we’re better served here thinking in emojis rather than words for my reaction—for instance, the exploding head, or the holding-back-tears, or the face-with-open mouth.

Over the years I had asked everyone I met for recordings, photographs, picks, guitars, diaries, anything of Iggy’s that was tangible, that I could hold or experience and which would bring him alive. Some said they had recordings, but they didn’t. There was a guitar he had owned and which I traced to Canada but got no closer to. One said Iggy had recorded a pilot for a music show that was never launched on Pakistan Television. Their archives were a shambles. There was an amp he had used, a jingle he had recorded, all arriving at dead-end upon dead-end upon dead-end. I tried to dig out his death certificate, but the hospital said they didn’t keep documents beyond twenty years. No newspaper published an obituary. Many days I didn’t only question why I was chasing him, I wondered whether I was chasing shadows of a dead ghost.

And now, suddenly, Dolan offering to play his music and put it on a USB so I could keep a copy.

There were eight different pieces in all, three of which were covers (“Yesterday,” “Killing Me Softly,” and “Hotel California”) from live performances. The rest were Iggy’s own compositions, recorded between 1981 and 1983. They were completely unexpected, because a couple of the pieces were pure electronic music. They were created, according to Dolan, when Iggy got his hands on the Casio VL-1 digital synthesizer (remember that tiny white keyboard, which you could almost but not quite fit into your pocket?).

All these years I had chased Iggy as a rock guitarist and here he was, with this fairly basic instrument, creating a track that wouldn’t sound out of place on a Daft Punk record (and a genuine low-key banger), and another from the oeuvre of Giorgio Giovanni, the spiritual father of Daft Punk—the father, in fact, of disco and dance music. A couple of people had spoken of Iggy’s distaste for disco, which was sweeping through the scene at the time. Perhaps his horizons—his genius?—were broader than anyone knew.

On the guitar pieces, Iggy riffed over a synthesizer beat and this was also Not Rock. It was funk overlapping with progressive jazz overlapping with disco overlapping with all sorts of wonderful ideas. There’s a little over thirty minutes in all, not nearly enough for an album, not even coherent in a way that could be an album. The recording quality was poor. And this was Iggy messing around. But you can sense the energy and joy in his compositions—Iggy in his element, nobody slowing him down, nobody forcing him to play covers. And it’s more than enough to showcase the vastness of his range.

I passed the recordings recently to Zahra Paracha, a musician, as a kind of stress-testing to see how they hold up. Zahra is one of Pakistan’s most compelling musicians and producers. She was struck by the futurism of Iggy’s electronic tracks. She noted things only an expert ear could, about the attention he paid to basslines (unusual, she said, for Pakistani musicians), or his adeptness with chordal structure, which is essentially how harmony progresses. He knew its rules so well he was basically disobeying them and getting away with it. In the Daft-Punkish banger, he switched mood in ways that reminded her of Jacob Collier, the genius British multi-instrumentalist.

A musician, she concluded, operating far ahead of his time.

***

In January 2023, I stood by the building from which Iggy fell to his death, maybe even on the spot where he had landed. It was not the Hotel Metropole. Neither was it as simple as suicide. But it was about a girl. I was in Doli Khata, a Saddar locality for which directions are invariably approximate and involving two Karachi landmarks: it’s behind Capri Cinema and close to Holy Family hospital. The area was in the kind of disrepair from which there is no repair, a victim of the unplanning that defines so much of Karachi. Decaying apartment blocks; half-finished buildings with flats piled on top of stores; unexplained detritus strewn around; rickshaws, bikes, cycles and pedestrians jostling for space on unpaved, narrow lanes; overhead the mesh of electricity cables, like fraying threads holding the edifice together.

This was the building Dolan had moved to after he got married. Five stories high, seventy-two flats and committedly unwashed. The lightwell inside gave it an unexpected bit of architectural relief. Iggy was staying with Dolan in his fourth-floor apartment when, on April 7th, 1984 he fell out of the window. It is likely he died before he hit the ground, electrocuted after becoming entangled in the electricity cables on the way down.

I was there to try and make some sense of his end, to visualize how it might have happened. It was a traumatic, violent death even if the violence was not inflicted upon him. At least not by anything other than fate—though fate, as we know, can be as petty and mean as the next guy. Based on several accounts, his death lay somewhere between a suicide and an accident. Such were the circumstances and the recollections of those close to him; it’s difficult to be sure. There was heartbreak for certain. The girl he loved had left him—maybe even, people said, for a friend of his. That hit him hard, triggering a mental health episode which ended with him on medication and convalescing at Dolan’s house. That meant he may not have been fully in control of his actions during the final moments of his life. The only person in the room with him at the time was his mother, who tried to stop him.

Truthfully, though, I am still not sure why I went there. In spirit and in soil, this locality might as well have been in a different country than the place in which Iggy fell. Nobody remembered him because nobody from that time was still here. There was no plaque.

Perhaps I was there as a ritual—something I did whenever I returned to Karachi. Find a new place to eat, find some new music, spend time with family, and then go and tend to my secret.

For a long time, I was stuck on finding the girl. If only I could speak to her it would unlock one final level of Iggy, the true circumstances of their break-up and his death. I had met his brothers and bandmates, spoken to his students and fans and employers. The love of his life, I was sure, would bring me close to Iggy like nobody else, enough to complete this story. But people either didn’t remember her, or didn’t want to tell me who she was. When I finally did confirm her identity, I was told by her friends and family not to reach out. Even after forty years there remained sensitivities and a degree of trauma and grief not worth reawakening.

Sometime between meeting Dolan and coming to the apartment block in Saddar, I did find Iggy’s eldest brother Ryan. He was at the Dar ul Sukoon in Karachi, a home for the elderly who have been abandoned or have no family. He was suffering from a mental health condition. He was firm that Iggy had committed suicide and that the mental health episode that led to his death was an undiagnosed and more permanent condition. Both Ryan and Dolan have since passed.

All that remains of their kid brother is a well-maintained grave in Karachi’s Gora Qabristan, the city’s main Christian cemetery, bearing these words:

Your guitar played your every mood God heard,

He understood

Smiling you joined his band above

To sing peace joy & love

With a silent tear

Savior dear

We lay at thy feet

Our precious treasure

That and, in the recordings, my little piece of him.