It’s hard to imagine history more irresistibly told than it is in The Swan’s Nest, Laura. McNeal’s novel about the love affair between two giants of nineteenth century poetry, Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett. Its contours are, surely, familiar to many — or at least, the letters between them, whose first object of love was verse. McNeal brings us inside their love and lives with a daring imagined intimacy. Or at least, I dare you not to be rapt by the first sentences of this text, which didn’t make it into the final version of the novel. And then imagine what did.

—Jina Moore Ngarambe for Guernica

There was a time when he was just one syllable or two, and his sister Pinkie called across the yard at twilight, Eb! Ebby! Come home! and he ran in his limber body over the grass at Cinnamon Hill, Jamaica.

He has never been back. Horses and carriages pass the heavily draped window with a growing frequency as the hour for dinner nears. A fist pounds dough, people run upstairs, china rings as it’s placed on tables. Every sound is the sound of a person who must be paid or who will ask for money to pay another.

His tea, which he has taken without sugar for more than forty years, has gone cold while he writes letters that must be answered to effect delays. He writes and writes until one letter remains, the one that since it came on Tuesday has gnawed like a mouse in the wall. The sender is not famous except in a small way, the kind of fame that comes to those whom practically no one can understand except those who are willfully difficult themselves.

Robert Browning, Piazza San Felice, Florence Italy.

His daughter’s husband.

He drinks the cold bitter tea and listens to the maid set the table in the next room. Mr. Barrett could simply add Mr. Browning’s letter, unread, to the other unread letters in the long wooden sleeve that fits into a slender crevice. In this sleeve lie eight very small unopened letters from Elizabeth herself. Elizabeth known as Ba.

People seem to wonder about the estrangement more and more. He hears Arabella talking about it with Henrietta. How could he cut Ba off this way?—she who was his favorite? To go on ignoring her all this time—five years! To leave unbroken every cold wax seal, even the black ones that say I write to inform you of a death.

It awes them. Perhaps, if he is fortunate, it teaches them.

When Elizabeth was a tiny thing as brilliant as the sun, he gave her his confidence, his faith, his love. When she became ill, he sent her to live at the sea. Then the sea killed Edward, his oldest boy, swallowing him up like Jonah. Elizabeth lived; Edward died. After that, he kept Elizabeth safe in London, and every night at 11:00, Mr. Barrett had gone to the room that had been fitted out and heated for her comfort, and they had talked and prayed together. For two of those years—two whole years—she was writing to and seeing Mr. Browning. Conniving together.

Mr. Barrett cracks the seal on Mr. Browning’s letter. The paper seems almost to unfold itself, the words to read themselves.

We are coming to England… your grandson… we wish him to know you… be reconciled.

Is he a monster?

The letter does not ask this question explicitly.

Mr. Barrett pulls the knob on the desk and slides out the shaft with its crevices that smell of mold and dust. Ba’s letters are there, the ones Henrietta has secretly removed and studied—he has seen her run a fingertip over the seals–to see if their father still has a beating heart.

What Henrietta cannot know is how it feels when the hand that wrote to you in love and devotion begins to write that it has not done anything wrong. “To lose a child is the greatest agony,” they say, and it is. But you lose them all anyway, don’t you. They grow up and the child disappears.

He takes a sheet of writing paper, and he dips his quill. Why can he not write the words? I would love to see you all, Mr. Browning…

A knock comes at the library door—“Dinner, Sir”—and the window panes like slabs of riven ice distort the dark bodies of carriages going by. He dips the quill and the ink dries on its carved point. Set the life against the act, she wrote when she left, and forgive me. But life is changed by the act—does she not see that? Her life is like water that has been poured out.

He folds the paper on which he has written nothing. He uses it to seal up the unopened letters from Ba and writes the name swiftly:

Elizabeth Barrett

But does not add her new name, Browning.

He writes the direction as indicated on the back of Ba’s letters to him.

Piazza San Felice

Florence, Italy

The unwritten letter, just an empty page, and the return of her unread words, will say the only thing he knows to say. The door will not open. The door is boarded up. The door has no key.

He makes a show of entering the dining room–a cheerful, welcoming show. “Hello, Arabel,” he says. “Henrietta. Occy. Setty.”

They wait for him to bless the bodies of the grouse, legs up, that the maid slides deftly onto plates.

“What have you done for others today?” he asks, the familiar opening, one that ties them all, he hopes, to a common purpose. Mr. Barrett searches for meat within the grouse’s collapsed bones. When they have answered, he says, “A letter came from Italy today.”

Everyone at the table waits to see if Mr. Barrett will say Ba’s name. If the dam will break, the glacier melt. Arabella says nothing, but her face is intent on this news as it is intent on the face of an ill person whose suffering she might ease.

“Didn’t she tell you?” Mr. Barrett asks. “She writes to you, I know. You needn’t pretend.”

Mr. Barrett uses the tip of his knife to separate the tiny bones of the grouse, and he finds a sliver of meat. Its softness makes it disappear without chewing. In the glow of the rush light, Setty and Occy clean their plates, and Mr. Barrett studies, for the millionth time, what his daughter Henrietta is holding in Artaud’s painting from 30 years ago: a black string tied around the neck of a black songbird, a reference to the West Indies, they all realized too late. Henrietta’s eyes look upward at the bird. Ba stands beside her, aged 12, the scroll in her hand representing her poems—that much they all understood and approved when the artist received his cheque. Elizabeth Barrett, the Poet Laureate of Hope End. Mr. Barrett has never understood why Artaud painted Edward, the eldest boy, to look foppish and idle, his shirt open to the waistcoat. Why had his wife not insisted on a proper man’s suit of clothes, and the placement in Edward’s hand of a book, quill, or compass?

Knives clink in the dining room. Each child that is not a child anymore says, “Good night, good night, good night.” The insistent wheels and clopping hooves of a coach on Wimpole Street grow louder and then fade away, and then, as happens more and more lately, the feeling engulfs him. It has depth and texture, is both heavy and dark. It is like the apprehension of a fact forgotten in sleep. It is the ship, of course. He is afloat with his sister Pinkie, nine, and his brother Mish, five. He is seven. He knows Pinkie is beside him because of her ragged breathing in sleep, and he can feel her nightdress but see nothing at all, as if he is blind or in a cave. The sloshing of water and the groaning of wood reminds him they are in the great ocean between Jamaica and England. When they get to England, if they ever do, his mother will not be there, nor Vertiline nor Vertiline’s daughter, who helped take care of him. The water sloshes and the light of the lantern reveals the blistery wall of his cabin, which he scratches to find that part of it which can be peeled.

“I want to go back,” he says.

“You can’t.”

“I will. I’ll stay on the ship.”

When he cries, she says, “Stop it. Think how Vertiline felt.”

“How she felt when?”

“When they captured her.”

“Who captured her?”

“Are you so stupid?”

“No,” he says, but he is. He doesn’t know she came to Jamaica in a ship where the people had this much space to breathe (and Pinkie puts her hand so close to his nose that he can feel the heat of it and smell her sweet coppery sweat.)

“Why?”

“To make sugar.”

“Who captured them?”

“Who do you think?” The sick feeling that began at that moment and never went away is born. Their father. Their uncle.

“Take your thumb out of your mouth,” Pinkie says.

Eb feels for the lump on his shoulder, square-ish and fiery-hot, proof that the mosquitos have followed him though his mother swore they couldn’t. In England, she said, the air would be cool and sweet.

“Are you scratching now?” Pinkie asks. “Stop it.”

Their mother said to count to a hundred and the itching would stop. He could never count past ten before he was at them again.

His sister feels around in the narrow ship-bed until she finds the glove that’s supposed to prevent thumb-sucking and bite-scratching. The itching rages on his ankles and thighs, and his insides crave the feeling only sucking his thumb gives him. He bites the skin of his knuckles through the glove and he starts to count to ten.

Pinkie died at school before she saw the portrait Lawrence made of her. The wide satin ribbons float down from her glossy pink silk bonnet, and her thin white dress, pressed against her slender body by the wind, is made whiter still by the stormy sky. She looks, on that precipice, very solemn and cast down, as if she has been told to think about the Future. Her expression is serious, but she holds her arm chest-high in the way she used to stand on the lawn. She is practicing the dance the Scottish tutor taught them before they were sent away from Jamaica.

If she’d lived, she would have told people how many times she’d had to wash the glove out in a bit of sea water because Eb would scratch his mosquito bites and get blood all over the linen. The other glove had blown overboard when she handed it to him to hold, and they had watched it bob for a few seconds before it became a white thing in a sea of frothy white waves and sank down to where the mermaids lived, or so she told him.

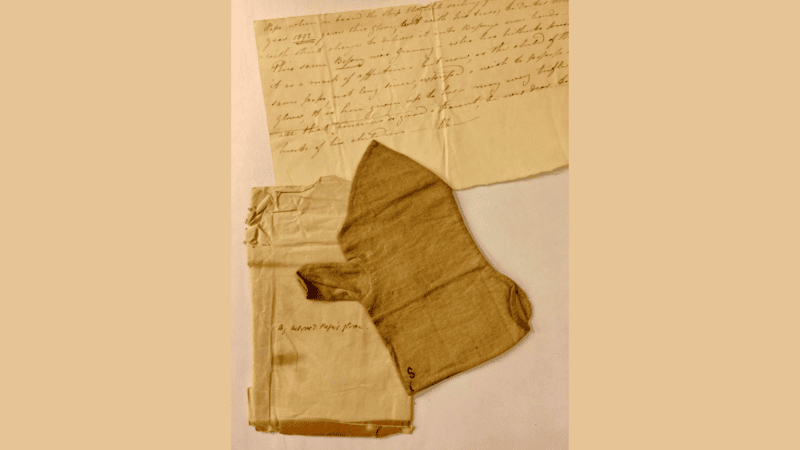

A hundred times, or a thousand, his mother had trotted out the little glove and told the story. She told it every time a sad or resigned mother talked of sending her boy to school. He always knew when she was about to tell it again. “How my Edward used to suck his thumb!” she would say, opening her Chinese box to pull it out for show. “So I made him a pair of these, you see, with a cover for his dear little thumb. See? And when I had to send him to England, he sent the glove back to me. ‘Tell my mother,’ he said, ‘that it’s wet with my tears.’”

The glove lay in Popish Italy now, with Ba and Mr. Browning. She took it with her because he gave it to her. He should not have.

Mr. Barrett tries to make out the bird he knows is flying in Artaud’s painting, in the dark part behind the children’s heads, but he cannot even see the string in his daughter’s fingers, which seem to curl around an object no longer present as her eyes look heavenward for a sign.

Mr. Barrett goes back to the library to finish his work. He lights the heater for his sealing wax and watches it melt, filling the bowl like red soup. Then he pours the wax on the paper folded to carry Ba’s letters back to her. The metal peels away with a small, satisfying crack, and he puts the packet with the other letters for the maid to hand over in the morning. Arabella or Henrietta might finger through the bundles– surely one or the other will–and whoever is sent to spy might see how thick this packet is. They’ll wonder if he has forgiven her at last, if he has come to his senses. They know nothing, nothing at all, about parenthood.

Laura McNeal’s book, The Swan’s Nest, is out this month from Hachette.