This month, Guernica looks at what we want — who we want — and how on earth, or anywhere else, we can possibly survive our own wanting.

We lead our June issue with a diptych on desire and the divine. MM Gindi and Enzo Escober, coming of age as queer young men at different times, in different parts of the world, in homes with different Christianities, forge their queerness with and against the expressions of God that surround them.

Enzo Escober grew up in the Philippines; though his family was not Catholic, he was enamored of the Catholic martyrs and the redemption they offered. “When I was seven, with my book of saints, I wished to be broken like a spotless thing, to be granted God for it,” he writes. But when Escober encounters the story of Matthew Shepard, two decades after the young man’s murder, he uncovers the limits of martyrdom. “[N]obody valued his murder more than liberal groups, whose fixation on his identity was symptomatic of a transformative politics dependent on death . . . a ritual purging of homosexuality’s moral stain,” Escober writes. But where is the room in the myth for a queer man to live, spotless or otherwise?

“I’m scared to write about the devil because writing is a form of incantation, because naming a thing is the first step in manifesting. I’m forty-five years old now and thought that time had diluted the fear, but writing about him exhumes it,” MM Gindi writes. “But I keep returning to this essay, or it returns to me. It haunts me, and I haunt it back.” The devil, in his case, is queer desire. Or rather, the devil exploits that desire, tunneling through otherworlds to reach for Gindi’s soul. Gindi knows what this looks like, how it works, because he watched The Exorcist as a young boy, and because a generation before, his father witnessed exorcisms as a young man. “From a young age, I am taught that the devil is always chasing me and that my job is to keep running,” he writes. “Because I’m gay, I have to run the fastest.”

In Meredith Talusan’s short story, “Sexual Tension,” the protagonist glories in desire, even in spite of themself. Surprised by a desire so strong it trumps career ambitions — desire by another name — they succumb to fantasy, and then flirt with its reality, each threatening an identity constructed, lately, to work as commodity. And in fiction from Spotlights, our series highlighting work from independent literary magazines around the world, a Nigerian woman who desires nothing more than to have a child must reckon, instead, with helping her niece end an unwanted pregnancy. After a lifetime of mothering without the identity or status of mother, she must perform an act that undoes the very thing she most wants in the world — because “this girl I had raised, my child even though she hadn’t come from my body, was despairing.”

In our latest Back Draft interview, Brandon Taylor gives up writing, returning only when he understands that he must want something more for his protagonist. In Wish You’d Been Here, our series documenting the disappearing rituals of a rapidly warming world, one man in the Himalayas finds himself alone in wanting nothing more than a timely spring bloom. In “Administrator,” by Sam Munson, a man who reluctantly becomes the keeper of his neighbors’ keys discovers the pleasure and pain of wanting in isolation.

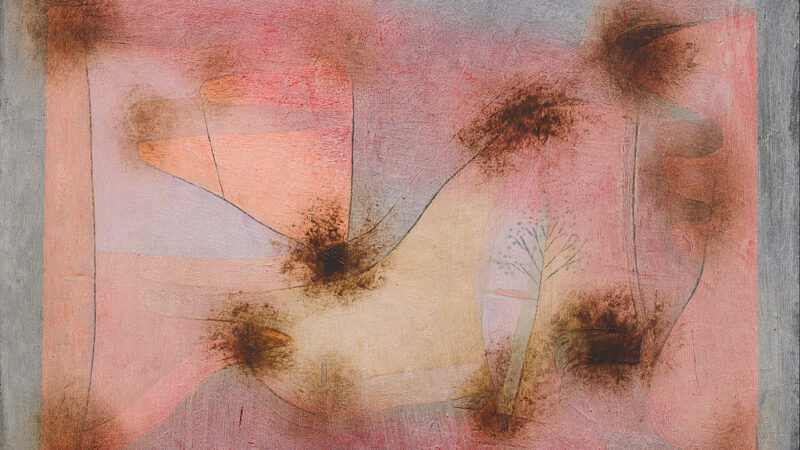

Omotara James’s poem “Closure” bears witness to the end of desire, while Dmitry Blizniuk crafts poetry around its absence. And Victoria Chang’s ekphrastic poem “Untitled IX, 1982” twists through desires light and dark to understand the expressive limitations of wanting: “What we say, here, now, is only the / part of flesh that is known.”

Thank you for being here.

— Jina Moore Ngarambe for Guernica